Entrepreneur, writer, musician, humanist

Fr. Matteo Ricci (left) and Xu Guangqi (right) in the Chinese edition of Euclid's Elements published in 1607. Jesuits began to show up in China in the 16th century, soon after the discovery of the New World, but Christianity had reached the Far East centuries earlier. (See special note in the Appendix.)

I’m going to assume you’ve never been to China. If that’s not the case, excuse me… but then if you knew China at all I don’t think you’d ask this question. I am not Chinese and I don’t speak Chinese (much to my dismay) but I do spend a heck of a lot of time there, relatively speaking, and perhaps I have some small insight on this. I’ll also say from the start that I am an atheist.First… making it worse? I think you don’t understand China, you don’t understand atheism and I’m willing to bet you don’t much understand the concept of religion, outside of your own, which I’m going to take a wild stab at and assume you’re Christian.First, not all religions are like the Abrahamic religions. Eastern religions are much more flexible, and Chinese traditional “religions” are in many ways more like philosophies than what your concept of religion probably is. China traditionally had two “religious” currents, Taoism and Confucianism. I’m not going to get into a long discussion about these, but neither is really predicated on “god” per se, certainly not on a creator god. Both go a long way to give ideas about how to live your life, the meaning of duty, etc. but both are traced to a normal, non-divine human being (Lao Tse in the first case and Confucius in the the second). Both are considerably older than Christianity, by the way. In the first century BCE, Buddhism was brought to China and it became the third major religion. It too is traced to a non-divine human being (Siddhārtha Gautama), and in many of its forms it too does not really have a “god” in the way you would think of one.These three religions were no more contradictory in the minds of the Chinese over the millennia than three different philosophies might be and most people kind of mingle them (certainly the first two). Indeed, once again, they are more philosophies than religions in many respects. You don’t go to church, you don’t even really pray (although Taoism and Buddhism are big on meditation), there typically is no concept of a creator god, and none of them are really big on proselytising. You are aware, I’m sure, of buddhist (and Taoist) monasteries, but these are largely devoted to meditation, which is a personal thing. Now, I’d point out that in the absence of any kind of priestly hierarchy, there are many different sects and currents of these, and some are vaguely more similar to the Abrahamic religions, but typically not.

The idea of an exclusive, creator-centered religion in which someone has a line to god, tells you what’s right and what’s wrong, etc. is foreign to Chinese culture (and to many far-eastern cultures… and I’m leaving Hinduism out of this). It is also the case in Japan, for example. As such, for many Chinese through the ages, you probably would have always considered them atheists because while they had “religions” of sorts, they didn’t really have a god.

For my part, I kind of bemoan the lack of “religion” too in China, even though I’m an atheist. Why? Because Taoism as a philosophy I find extremely appealing, and to a lesser extent, Confucianism. Many of the Chinese I deal with seem extremely commercial to me, very focused on the day-to-day and out of touch with the broader, philosophical questions that underlie their traditional philosophies. I think that some more attention to Taoist teachings would do many Chinese well. However - and this is a big however - most Taoists would still be atheists by your book.

Therefore, the state of affairs that you bemoan is just China. Your idea of “making it better”, and asking religious people to develop religion in China would probably consist of trying to proselytise an entirely foreign concept into a 5000 year old culture, introducing what I consider to be superstition to a people with a rich “spiritual” history of their own that never needed a vengeful god. There are 1.4 billion people there, some would buy your story, but I am sure you would fail dismally on the whole and I am very glad of that.

Kevin Dolgin in his own words: I am a serial entrepreneur (I have created companies in the United States, France, Great Britain and soon in China), an associate professor at the Sorbonne, an active musician and a writer (feel free to check me out on Amazon). I am originally from New York but I have lived in Paris for 30 years and am a dual citizen. I am also an avid student of history and of human behavior.

Kevin Dolgin in his own words: I am a serial entrepreneur (I have created companies in the United States, France, Great Britain and soon in China), an associate professor at the Sorbonne, an active musician and a writer (feel free to check me out on Amazon). I am originally from New York but I have lived in Paris for 30 years and am a dual citizen. I am also an avid student of history and of human behavior.

A Jesuit—Chinese world map, produced in the 16th century. Note the amazing accuracy of the map in regard to Europe, Africa and Asia, with the Americas a bit less accurate, although they were aware that the new gigantic continent comprised two hemispheres.. (Click on image for best appreciation.)

A note on the Jesuit China Missions

The following material is excerpted from Wikipedia.

The history of the missions of the Jesuits in China is part of the history of relations between China and the Western world. The missionary efforts and other work of the Society of Jesus, or Jesuits, between the 16th and 17th century played a significant role in continuing the transmission of knowledge, science, and culture between China and the West, and influenced Christian culture in Chinese society today.

The first attempt by the Jesuits to reach China was made in 1552 by St. Francis Xavier, Navarrese priest and missionary and founding member of the Society of Jesus. Xavier never reached the mainland, dying after only a year on the Chinese island of Shangchuan. Three decades later, in 1582, Jesuits once again initiated mission work in China, led by several figures including the Italian Matteo Ricci, introducing Western science, mathematics, astronomy, and visual arts to the Chinese imperial court, and carrying on significant inter-cultural and philosophical dialogue with Chinese scholars, particularly with representatives of Confucianism. At the time of their peak influence, members of the Jesuit delegation were considered some of the emperor's most valued and trusted advisors, holding prestigious posts in the imperial government.[citation needed] Many Chinese, including former Confucian scholars, adopted Christianity and became priests and members of the Society of Jesus.

According to research by David E. Mungello, from 1552 (i.e., the death of St. Francis Xavier) to 1800, a total of 920 Jesuits participated in the China mission, of whom 314 were Portuguese, and 130 were French.[2] In 1844 China may have had 240,000 Roman Catholics, but this number grew rapidly, and in 1901 the figure reached 720,490.[3] Many Jesuit priests, both Western-born and Chinese, are buried in the cemetery located in what is now the School of the Beijing Municipal Committee.[4]

Contacts between Europe and the West already dated back hundreds of years, especially between the Papacy and the Mongol Empire in the 13th century. Numerous traders – most famously Marco Polo – had traveled between eastern and western Eurasia. Christianity was not new to the Mongols, as many had practiced Christianity of the Church of the East since the 7th century (see Christianity among the Mongols). However, the overthrow of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty by the Ming in 1368 resulted in a strong assimilatory pressure on China's Muslim, Jewish, and Christian communities, and outside influences were forced out of China. By the 16th century, there is no reliable information about any practicing Christians remaining in China.

Fairly soon after the establishment of the direct European maritime contact with China (1513) and the creation of the Society of Jesus (1540), at least some Chinese became involved with the Jesuit effort. As early as 1546, two Chinese boys enrolled in the Jesuits' St. Paul's College in Goa, the capital of Portuguese India. One of these two Christian Chinese, known as Antonio, accompanied St. Francis Xavier, a co-founder of the Society of Jesus, when he decided to start missionary work in China. However, Xavier failed to find a way to enter the Chinese mainland, and died in 1552 on Shangchuan island off the coast of Guangdong,[5] the only place in China where Europeans were allowed to stay at the time, but only for seasonal trade.

A few years after Xavier's death, the Portuguese were allowed to establish Macau, a semi-permanent settlement on the mainland which was about 100 km closer to the Pearl River Delta than Shangchuan Island. A number of Jesuits visited the place (as well as the main Chinese port in the region, Guangzhou) on occasion, and in 1563 the Order permanently established its settlement in the small Portuguese colony. However, the early Macau Jesuits did not learn Chinese, and their missionary work could reach only the very small number of Chinese people in Macau who spoke Portuguese.[6]

A new regional manager ("Visitor") of the order, Alessandro Valignano, on his visit to Macau in 1578–1579 realized that Jesuits weren't going to get far in China without a sound grounding in the language and culture of the country. He founded St. Paul Jesuit College (Macau) and requested the Order's superiors in Goa to send a suitably talented person to Macau to start the study of Chinese. Accordingly, in 1579 the Italian Michele Ruggieri (1543–1607) was sent to Macau, and in 1582 he was joined at his task by another Italian, Matteo Ricci (1552–1610).[6]

Ricci's policy of accommodation

Both Ricci and Ruggieri were determined to adapt to the religious qualities of the Chinese: Ruggieri to the common people, in whom Buddhist and Taoist elements predominated, and Ricci to the educated classes, where Confucianism prevailed. Ricci, who arrived at the age of 30 and spent the rest of his life in China, wrote to the Jesuit houses in Europe and called for priests – men who would not only be "good", but also "men of talent, since we are dealing here with a people both intelligent and learned."[7] The Spaniard Diego de Pantoja and the Italian Sabatino de Ursis were some of these talented men who joined Ricci in his venture.

Just as Ricci spent his life in China, others of his followers did the same. This level of commitment was necessitated by logistical reasons: Travel from Europe to China took many months, and sometimes years; and learning the country's language and culture was even more time-consuming. When a Jesuit from China did travel back to Europe, he typically did it as a representative ("procurator") of the China Mission, entrusted with the task of recruiting more Jesuit priests to come to China, ensuring continued support for the Mission from the Church's central authorities, and creating favorable publicity for the Mission and its policies by publishing both scholarly and popular literature about China and Jesuits.[8] One time the Chongzhen Emperor was nearly converted to Christianity and broke his idols.[9]

The influence went both ways

For over a century, Jesuits like Michele Ruggieri, Matteo Ricci,[44] Philippe Couplet, Michal Boym, and François Noël refined translations and disseminated Chinese knowledge, culture, history, and philosophy to Europe. Their Latin works popularized the name "Confucius" and had considerable influence on the Deists and other Enlightenment thinkers, some of whom were intrigued by the Jesuits' attempts to reconcile Confucian morality with Catholicism.[45]

A further note on Fr. Ricci

Zenit.org /

Book review excerpt of The Wise Man, by Vincent Cronin

Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci was not an ugly imperialist Westerner (those would come later) and represented with tact, respect, and honor the best that Europe could offer Chinese civilization in sciences, mathematics, and technological and philosophical notions.

A new edition of the book, The Wise Man from the West by Vincent Cronin, is the amazing story of the famous Jesuit missionary priest to China, Fr. Matteo Ricci. He arrived in China in 1582 and died there twenty-eight years later, having developed a deep knowledge of and love for the country, the culture and the people. For this, Fr. Ricci was revered as a “Wise Man” by the Chinese.

Before Ricci’s heroic mission, China was an unexplored land bordering on the vague, mysterious Cathay, and the West was no more than a rumor to the learned Mandarins, a distant unknown region lying beyond the bounds of geography. In the person of Father Ricci these two worlds met, and Vincent Cronin dramatically recreates the romance, the crossed purposes, and the potential tragedy of that meeting. He shows us ancient China, the timeless state, with a civilization older than that wherein Christianity first found expression.

Because Ricci loved this civilization and honored it, he was able to teach his strange new Christian doctrine with tact and sympathy. He carried much of the technological and philosophical wisdom of the late Renaissance Europe, and thus found favor among the Mandarins, the men of learning who enjoyed high status at the Imperial Court. He learned Chinese to discuss with them the problems in science and technology, and also questions of religion and the hereafter. He lived as a great scholar among great scholars and left behind him a memory worthy of the Christian faith he served.

Things to ponder

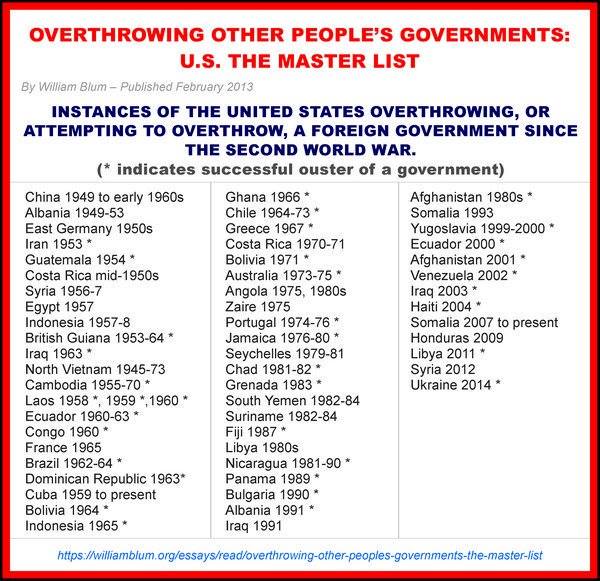

While our media prostitutes, many Hollywood celebs, and politicians and opinion shapers make so much noise about the still to be demonstrated damage done by the Russkies to our nonexistent democracy, this is what the sanctimonious US government has done overseas just since the close of World War 2. And this is what we know about. Many other misdeeds are yet to be revealed or documented.

Parting shot—a word from the editors

The Best Definition of Donald Trump We Have Found

In his zeal to prove to his antagonists in the War Party that he is as bloodthirsty as their champion, Hillary Clinton, and more manly than Barack Obama, Trump seems to have gone “play-crazy” — acting like an unpredictable maniac in order to terrorize the Russians into forcing some kind of dramatic concessions from their Syrian allies, or risk Armageddon.However, the “play-crazy” gambit can only work when the leader is, in real life, a disciplined and intelligent actor, who knows precisely what actual boundaries must not be crossed. That ain’t Donald Trump — a pitifully shallow and ill-disciplined man, emotionally handicapped by obscene privilege and cognitively crippled by white American chauvinism. By pushing Trump into a corner and demanding that he display his most bellicose self, or be ceaselessly mocked as a “puppet” and minion of Russia, a lesser power, the War Party and its media and clandestine services have created a perfect storm of mayhem that may consume us all.— Glen Ford, Editor in Chief, Black Agenda Report

In his zeal to prove to his antagonists in the War Party that he is as bloodthirsty as their champion, Hillary Clinton, and more manly than Barack Obama, Trump seems to have gone “play-crazy” — acting like an unpredictable maniac in order to terrorize the Russians into forcing some kind of dramatic concessions from their Syrian allies, or risk Armageddon.However, the “play-crazy” gambit can only work when the leader is, in real life, a disciplined and intelligent actor, who knows precisely what actual boundaries must not be crossed. That ain’t Donald Trump — a pitifully shallow and ill-disciplined man, emotionally handicapped by obscene privilege and cognitively crippled by white American chauvinism. By pushing Trump into a corner and demanding that he display his most bellicose self, or be ceaselessly mocked as a “puppet” and minion of Russia, a lesser power, the War Party and its media and clandestine services have created a perfect storm of mayhem that may consume us all.— Glen Ford, Editor in Chief, Black Agenda Report

Magnificent and brave answer. Nothing speaks louder about the moral and logical contradictions of the Abrahamaic religions, and their dominionism over nature—people and animals—than reading the Bible. Not to mention the wrathful, vengeful, jealous and vindictive, often bloodthirsty Gods of the Jews and the Christians. If God—as proclaimed by these zealots—boats these qualities, I am better than God, way better, and I want none of it, certainly not worshiping it. Reading the origins of the Crusades with an impartial mind—should that exist—is a sobering exercise about the meaning of “religion” in the West, and especially “Christianity.” Couched in lofty rhetoric,… Read more »

Thank you for this magnificent statement of the problem with the dominion religions (judaism, christianity & isam)… whose foundation is that of human supremacy. with the sanctified subjugation of all other beings on earth & the domination, control and ownership of nature…. I will use your words in the many articles that I post about the adverse effect of the genesis mandate on all those who do not fall under the umbrella of human supremacy…. including as you note thos who are not of the tribe and those who do not pay homage to jesus: Genesis 9:1-3 “The fear and… Read more »

Who says there is no religion in China…. China is a monotheistic nation where there is only one god: MONEY.

I am happy to hear that the Chinese are atheist. Religion destroys brain cells. There is no place for such superstition in the 21st century.

(Since WSWS censors thought, through ‘pending’. . . ) A dialectical approach to this would show you that: 1. Social identities, while being purely social constructs are real AND are the principal justifications for social oppression, i.e., racial and gender identities. 2. Ruling classes always devise social identities, even where they don’t exist, or are insignificant, to divide and conquer and obscure class struggle 3. The dominant social identity in the U.S. has ALWAYS been white & male supremacy 4. White and male supremacy have been the main social pillars of capitalist exploitation in the U.S. Male supremacy has been… Read more »

A very undialectical view of religion. And I’m not religious.

Study Marx on this issue.

Thank you for this great statement of the problem with the dominion religions (judaism, christianity & isam)… whose foundation is that of human supremacy. with the sanctified subjugation of all other beings on earth & the domination, control and ownership of nature…. I will use your words in the many articles that I post about the adverse effect of the genesis mandate on all those who do not fall under the umbrella of human supremacy…. including as you note thos who are not of the tribe and those who do not pay homage to jesus: Genesis 9:1-3 “The fear and… Read more »

Could not agree more Carolyn.

The reason most Chinese are atheist–I have asked them about this–is because the idea of a God in the sky seems ridiculous to them. For 5000 years they developed a highly cultured civilization ruled by ‘the Tao’, which is not based on a self existent entity. This is consistent with both Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism. One student, whose philosophy paper I edited, traced this to the fact that the Greek Gods on Mt. Olympus demanded obedience or punishment, and that concept tricked through Western religious traditions, not to mention being reinforced by the Hebrews who demanded that ‘no other gods… Read more »