Dara Kerr

CNET.COM

To track down the suspects, the FBI pieced together surveillance videos, cellphone records and social media conversations.

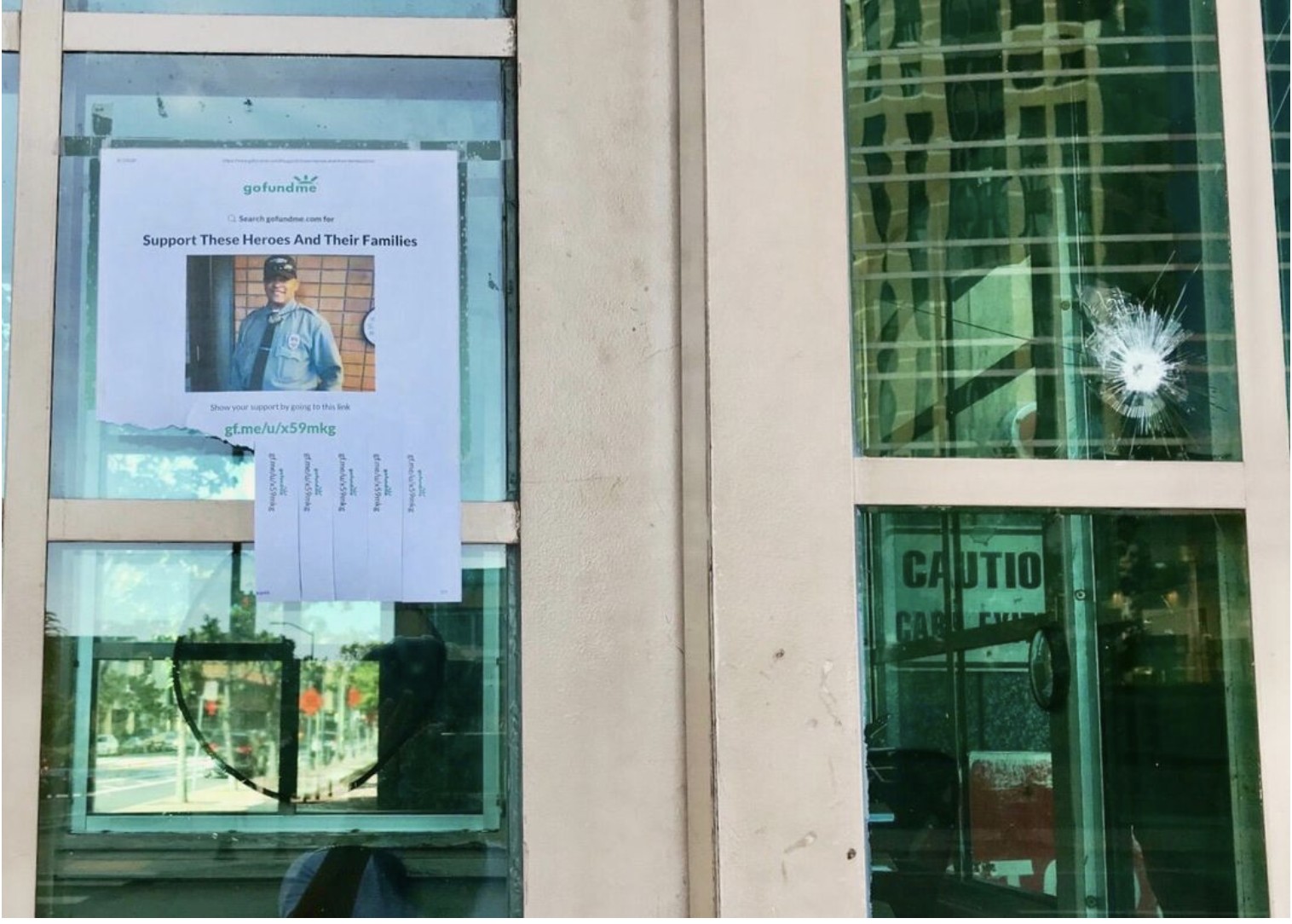

Bullet holes mark the guard booth where Patrick Underwood was working the night he was killed. A GoFundMe site has been set up for donations for his family. (Dara Kerr/CNET)

Steven Carrillo met Robert Justus for the first time when he picked him up at the San Leandro, Calif., train station on May 29. But the two were already familiar with each other, according to court documents unsealed earlier this week. They'd connected in a Facebook group that was geared toward members of the far-right extremist boogaloo movement.

The two men had reportedly hatched a plan to drive to Oakland, Calif., and attack federal law enforcement officers, according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. By the end of that night, Dave Patrick Underwood, a federal security guard, would be dead and his colleague severely injured.

The alleged murder was coordinated to take place at the same time as mass protests against the death of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man who was killed in by a white police officer. For Carrillo, 32, and Justus, 30, the protests would serve as a cover for their plot, according to court documents.

"Go to the riots and support our own cause," Carrillo wrote in the Facebook group, referencing the boogaloo movement's anti-government beliefs and desire to spark a second civil war. "Use their anger to fuel our fire. Think outside the box. We have mobs of angry people to use to our advantage."

A cluster of Virginia "boogaloo" types at a recent protest. Being heavily armed in public is one of their signatures. Police are rarely seen to meddle with them, which is unthinkable if they were black. Their likely service to the state as shock troops against the left, or as agents provocateurs is obvious.

Facebook has increasingly become the place where extremist fringe groups coalesce and plan. It's where anti-government, pro-gun protesters coordinated demonstrations over coronavirus quarantines and where the far-right, neo-fascist group Proud Boys schemed to infiltrate George Floyd protests. Facebook is also where the boogaloo movement has taken off over the past year.

The movement is loosely knit and strongly opposed to law enforcement. The name comes from the 1984 cult film "Breakin' 2: Electric Boogaloo" and is used ironically to refer to a second civil war. Some members stay staunchly focused on anti-government activities and rhetoric, while others slide into white supremacist or neo-Nazi ideologies. In recent months, several boogaloo members took their activities offline and have been arrested for crimes, including building pipe bombs and conspiracy to commit an act of terrorism.

RELATED STORIES

Facebook is home to at least 125 boogaloo groups with roughly 73,000 members -- though some people might be in more than one group, according to the Tech Transparency Project, part of the nonpartisan watchdog Campaign for Accountability. More than half of the groups were formed between February and April. The Institute for Strategic Dialogue, a global think tank that studies extremism, has linked the growth of boogaloo members' online activity to the novel coronavirus pandemic, particularly in February and March. During those months, the institute reports that more than 200,000 posts across social media included the term "boogaloo" with 52% on Twitter, 22% on Reddit and 12% on Tumblr.

Boogaloo members supposedly showing support for the BLM protests. Since the Boogaloo movement (like Antifa) is a leaderless, loosely organised network of cells, it's impossible to ascertain whether what these people claim to be is true. Maybe they are simply undercover police or agents provocateurs, or it is a conscious maneuver by boogaloos to blend undisturbed with the rest of the protesters.

"Social media sites, like Facebook, serve as virtual meeting halls for people who not only like to chat, but for extremists," said Brian Levin, the director of the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University in San Bernardino. "You'll find that there's this whole ecosystem right out in the open."

While Facebook allows boogaloo groups to be active on its platform, the company said that earlier this month it stopped recommending them through its sidebar algorithm. Facebook also said it would remove any content with statements or images in boogaloo groups that depict armed violence. It also said anyone claiming a boogaloo affiliation who has attempted to commit mass violence will have their account pulled under its "dangerous individuals" policy.

The social media company said it has a team of 350 people with law enforcement, counterterrorism and radicalization expertise that study behavior related to violence on its platform. The team looks at new trends in speech and how various groups evolve over time on the site.

With 2.6 billion monthly active users on Facebook, however, a lot of violent and extremist activity can still fall through the cracks.

As for Carrillo and Justus' plan to attack law enforcement officers in Oakland, Facebook said it didn't pinpoint the plot until the day after it happened. Once Underwood was killed, Facebook pulled Carrillo's account under its "dangerous individuals" policy.

"We designated these attacks as violating events and removed the accounts for the two perpetrators along with several groups," a Facebook spokeswoman said. "We will remove content that supports these attacks and continue to work with law enforcement in their investigation."

The boogaloo boys show the potency of a well-timed message with the dry kindling that is the internet.

Joe Scarborough, the host of MSNBC's Morning Joe, was infuriated by Facebook's response and used his show to blast the company and its CEO and chief operating officer in a seven-minute tirade on Wednesday.

"Mark Zuckerberg and Sheryl Sandberg are only interested in protecting their billions," Scarborough said, his voice nearing a scream. "So when you find that a federal officer is mowed down by a right-wing extremist group and it's Mark Zuckerberg whose platform is promoting that group by pushing people to that group, then his words are meaningless."

Manhunt

Carrillo, an active-duty sergeant in the US Air Force, was driving a white Ford van when he picked up Justus at the train station on May 29.. As Justus climbed in, Carrillo offered him body armor and a firearm, according to court documents. Justus declined, so Carrillo told him to take the drivers' seat.

Earlier, Carrillo had briefly sketched out his plan in the Facebook group. The FBI obtained those conversations from Facebook with a search warrant.

Surveillance videos captured a person in a white van taking fire at a guard booth in Oakland, Calif. Hollywood juvenile fantasies of macho individualism are readily embraced by rightwing types. (The Federal Bureau of Investigation)

"It's a great opportunity to target the specialty soup bois," Carrillo wrote in the Facebook group, using a boogaloo term that refers to federal law enforcement agents. He added two fire emojis and a YouTube video showing a large crowd violently attacking California Highway Patrol vehicles.

"Let's boogie," Justus replied.

As the two men drove to downtown Oakland, the George Floyd protest was growing in size. Justus parked the van at about 9:30 p.m. in front of a federal courthouse, according to court documents. It was just three blocks from the protest. About 15 minutes later, he started up the engine and drove toward a guard post outside the courthouse. Carrillo then allegedly slid open the rear passenger side door and fired several rounds at the two security guards out front.

The FBI was later able to reconstruct much of this incident with surrounding surveillance videos and by tracking Carrillo's T-Mobile phone records. But that night, the two men got away. Justus went home and said he didn't see Carrillo again, according to court documents.

Hours after the shooting, Underwood's name started trending on social media with people blaming Black Lives Matter protesters for his death. President Donald Trump even mentioned it during a speech on June 1, saying, "These are not acts of peaceful protest. These are acts of domestic terror."

Those acts, however, weren't carried out by the protesters.

For Carrillo, the shooting appeared to be just the beginning. Eight days later, on June 6, he allegedly fatally shot Santa Cruz County Sheriff's Deputy Damon Gutzwiller and wounded another officer.

As the FBI pieced together the evidence from these alleged crimes, agents said they recovered several items linking Carrillo to the boogaloo movement. In his van, authorities said they found a ballistic vest with a patch that showed an igloo and Hawaiian-style print, both popular symbols with boogaloo members. At one point, Carrillo also reportedly used his own blood to write boogaloo phrases on the hood of a car, including "boog" and "stop the duopoly," referring to control of the Republican and Democratic parties.

Carrillo has been charged with murder and attempted murder. If found guilty, he could face the death penalty. Justus is charged with aiding and abetting murder and attempted murder.

Jeffrey Stotter, Carrillo's lawyer, said that beyond the federal complaint, he hasn't yet seen independent evidence linking Carrillo to the boogaloo movement. He said any calls for violence or violent action are unconscionable, but everything remains an accusation at this point.

"We're looking into what extent [the boogaloo movement] may have influenced Mr. Carrillo," Stotter said. "He certainly reported to express a great love for this country and a great love of what this country stands for."

It was unclear who was representing Justus at the time of publication.

The longstanding government benign neglect of armed rightwing militias is now showing its fruits in these acts of defiance. Steven Carrillo was an active-duty sergeant in the US Air Force. He's believed to be a member of the boogaloo movement and has been charged with the murder of a federal security guard. (Jeffrey Stotter)

Facebook said it's removed the groups Carrillo and Justus were members of and it will continue to review other boogaloo groups. It also said it will remove any content that praises what Carrillo and Justus allegedly did.

Levin, the director of the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism, said removing those few groups likely won't have much of an effect. The boogaloo movement will just continue to adapt, he said. Extremist groups used to be more largely organized, he added, but now they've become splintered and localized -- as was likely the case with Carrillo and Justus.

"The boogaloo boys show the potency of a well-timed message with the dry kindling that is the internet," Levin said. "You're going to see a lot of hornets making a lot of smaller nests."

CNET's Andrew Morse contributed to this report.

Read it in your language • Lealo en su idioma • Lisez-le dans votre langue • Lies es in Deiner Sprache • Прочитайте это на вашем языке • 用你的语言阅读

[google-translator]

Keep truth and free speech alive by supporting this site.

Keep truth and free speech alive by supporting this site.

Donate using the button below, or by scanning our QR code.

The best way to get around the internet censors and make sure you see the stuff we publish is to subscribe to the mailing list for our website, which will get you an email notification for everything we publish.

THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License