WRITTEN BY QIAO COLLECTIVE

Originally posted on AUG 5, 2021

The Trump Administration’s forced sale of TikTok is part of a broader effort to thwart Chinese economic independence in the tech sector

With TikTok, Donald Trump added State Department coercion to his “art of the deal” toolkit. After months of feigned concern that the viral TikTok app represents a “trojan horse” for the Communist Party of China to access U.S. consumer data, the Trump Administration issued the Chinese company an ultimatum: sell the app to a U.S. buyer, or be shut down.

Microsoft has stepped forward as a potential buyer of TikTok, a clone of the Chinese video app Douyin tailored for a Western audience. The app boasts some 100 million U.S. users and its parent company, ByteDance, has been valued at $100 billion.

Microsoft's advances, coupled with Trump’s stipulation that TikTok pay “a substantial amount of money” to the U.S. Treasury for facilitating the transaction, makes clear that this is not about protecting consumer data. Certainly, neither Silicon Valley nor Washington have legitimate concerns over security issues given the longstanding, well-documented collaborations between tech giants Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft, and others and the NSA, CIA, FBI, and ICE. But consumer protection is a convenient cover story for what’s really happening: the forced sale of TikTok under political duress is nothing more than a tag-teamed State Department/Silicon Valley highway robbery.

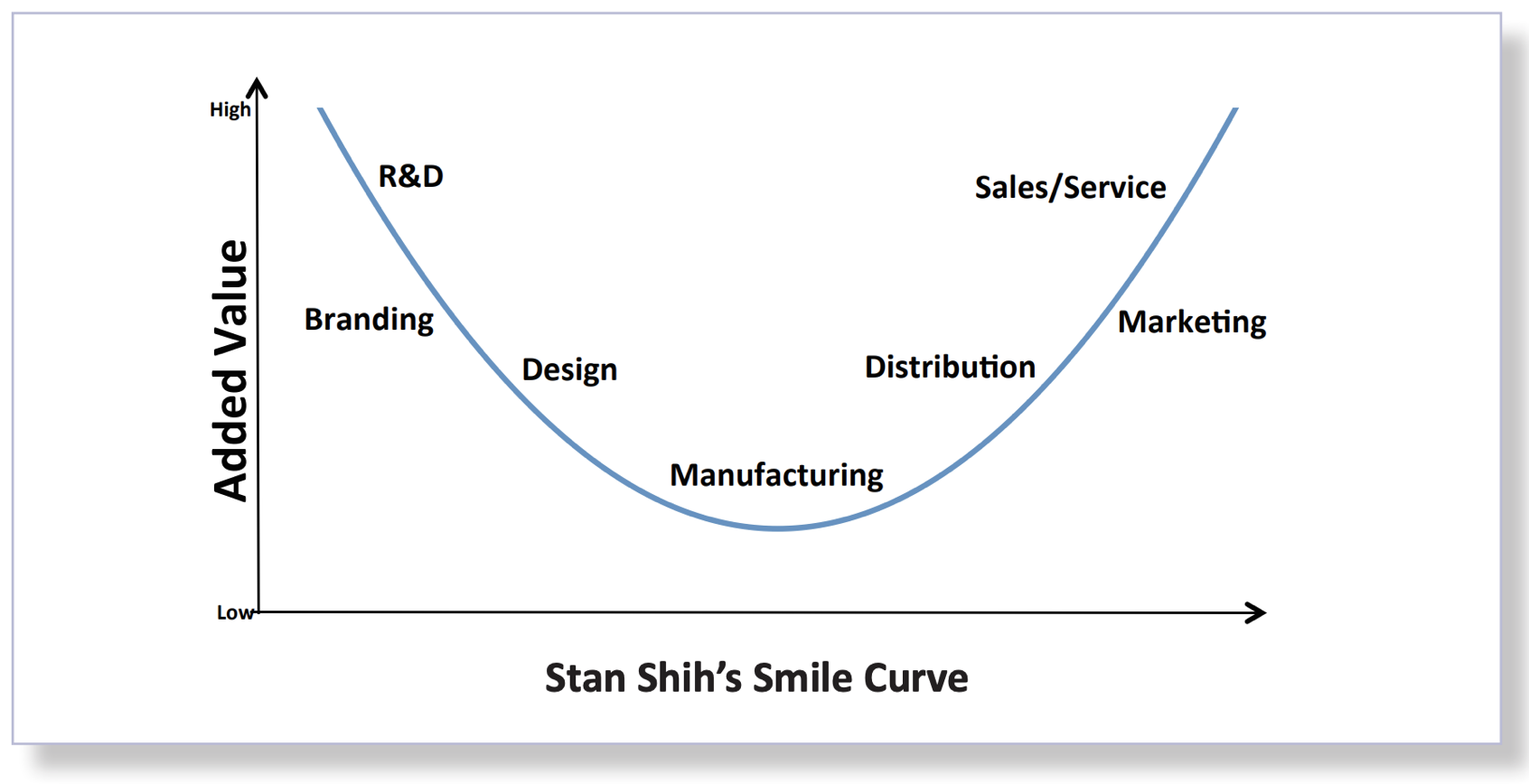

The TikTok saga is part of a larger geopolitical strategy to obstruct, isolate, and derail China’s burgeoning tech industry. China has identified technological innovation, via its innovative Made in China 2025 (MIC 25) initiative, as the cornerstone of its broader efforts to climb the manufacturing value chain and shed its role as the “world’s factory” to enter the domain of innovation and high-tech manufacturing. This top end of the value chain has historically been the exclusive domain of the U.S., Europe, and strategic allies such as Japan and South Korea.

The U.S. has unveiled a new digital containment doctrine designed to keep China in its historical place as a semi-peripheral manufacturing hub.

It’s now clearer than ever that the U.S. is unwilling to cede this technological supremacy without a fight. From the forced sale of TikTok to sanctions on Chinese telecoms giant Huawei, the U.S. has unveiled a new digital containment doctrine designed to keep China in its historical place as a semi-peripheral manufacturing hub.

Industrial modernization has been the key to Chinese socialist construction since the Mao era. For decades, the CPC identified “backward social production” and the people’s growing material needs as the principal contradiction facing Chinese society. Since Mao’s aspirations to grow industry and reduce foreign dependence by transforming China into a net steel exporter, making China technologically competitive on the world stage has been of paramount importance to Chinese socialist construction.

Ambitious plans such as MIC 2025 show how far China has come since Mao’s time of backyard steel furnaces. The economic initiative, first introduced by the State Council in 2015, aims to transform China into a global leader in AI, robotics, telecommunications, and information technology through subsidies, state-owned industry, and technology transfers.

Chinese officials have framed the initiative as a way to grow out of low-value manufacturing and bypass the so-called “middle income trap.” This vision of high-tech economic sovereignty runs in opposition to the economic role predetermined by the Western powers which mediated China’s entry into the global capitalist market over the last four decades. As the ‘world’s factory,’ China manufactures more than 90 percent of the world’s smartphones, but until recently, Chinese brands made up for a negligible share of the sales. China’s role as a low-value manufacturing hub—a source of cheap labor for the Apples and IBMs of the world and little else—was hugely profitable to Western capitalists. Of course, it also enabled China to capture some fraction of those profits in service of building up the nation’s productive capacity in service of socialist construction and investment in fostering competitive domestic industries.

The “smile curve” illustrates the high added value processes of industry. China has historically occupied the low value manufacturing region of the curve, a trend that MIC 2025 seeks to remedy.

For China to leap into the domain of name-brand consumer electronics is to disrupt the predetermined economic world-system of the West’s designs. So it’s no surprise that the unveiling of MIC 2025 has corresponded with an increase in Western economic antagonism towards the PRC. Invoking the imperialist language of free trade, EU and U.S. economic advisers railed against the plan for “undermining international trade rules” and “tilting the playing field in favor of Chinese players.” In the hypocritical language of free trade and open markets which has defined the neocolonial economic hierarchy of the “postcolonial” era, China’s state industry, subsidies, and prioritization of what it calls “indigenous innovation” amount to what the West demonizes as “discrimination” against foreign firms. (Never mind that many of these same economic policies defined the approach of the so-called “Asian tigers,” most of which were lauded due to their fealty to the U.S. geopolitical agenda.)

In this worldview, China is merely a mindless, massive factory, a copycat and trade thief at best, incapable of the kind of innovation and creativity necessary to be a world leader in consumer technology. The success of Huawei, TikTok, and other Chinese innovators proves that racist worldview wrong.

Embedded in these allegations is a paternalist sense that China should ‘know its place.’ A report on MIC 2025 for the European Union Chamber of Commerce warned: “China has been the world’s factory, and now it wants more.” The depiction of China’s development aspirations as ‘uppity,’ even aggressive, reveals the Western chauvinist mindset as to China’s ‘proper’ place in the global supply chain. In this worldview, China is merely a mindless, massive factory, a copycat and trade thief at best, incapable of the kind of innovation and creativity necessary to be a world leader in consumer technology. The success of Huawei, TikTok, and other Chinese innovators proves that racist worldview wrong.

Despite the trade war’s apparent focus on agricultural purchases and tariffs, many identified MIC 2025 as the quiet antagonist behind U.S. anxieties about China’s economic agenda. For instance, Lorand Laskai of the Council on Foreign Relations described MIC 2025 as “the central villain, the real existential threat to US technological leadership.” In fact, U.S.-imposed tariffs explicitly identified Chinese subsidies, state involvement, and protectionism as their central target. In testimony before the Senate in 2019, Bonnie Glaser of the Center for Strategic and International Studies noted that Chinese officials had “dropped references to MIC 2025 in official documents and authoritative media” in response to the heightened U.S. scrutiny and pressure. The aggressive use of tariffs and threats against the technological turn in China’s socialist construction makes clear that the so-called “trade war” was part of a larger imperialist agenda to stall China’s ascent of the global value chain.

However, the carrot and stick of trade war negotiations—a swan song for the era of Sino-U.S. engagement Mike Pompeo recently declared a “failure”—has given way to a hardline stance. In a digital upgrade of the Cold War containment doctrine, the U.S. is seeking to block China’s tech industry from key markets and supply chains altogether.

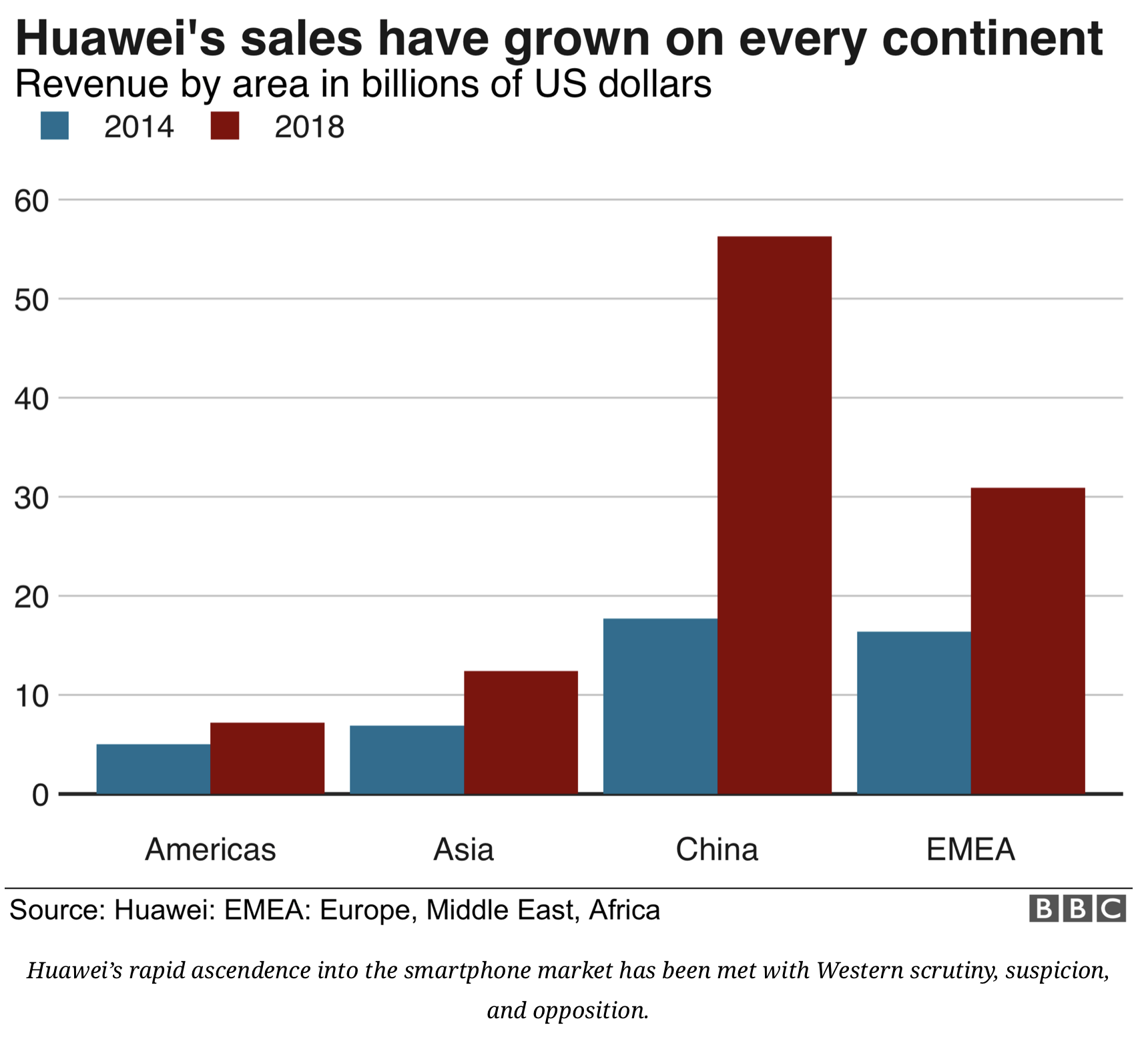

The threatened U.S. ban on TikTok—already banned in India and under scrutiny in Australia, EU, and Japan—is merely the latest attempt to draw a digital iron curtain around China’s flagship tech brands. For years, the U.S. has built the case that Huawei (which just eclipsed Apple as the most popular smartphone brand for Chinese consumers) is a proxy for the CPC’s alleged global ambitions. The State Department has thrown its weight around to pressure allies and client states to ban Huawei from building critical 5G infrastructure, threatening to cut off allies from U.S. intelligence if they were to be ‘compromised’ by Huawei infrastructure. At present, Huawei 5G is effectively banned from the U.S., UK, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Meanwhile, under U.S. governmental pressure, Google removed Google Play Store functionality from Huawei devices, effectively blocking Huawei users from ubiquitous apps such as Gmail, YouTube, and Google Play.

The threatened U.S. ban on TikTok—already banned in India and under scrutiny in Australia, EU, and Japan—is merely the latest attempt to draw a digital iron curtain around China’s flagship tech brands.

Even more, in May the U.S. moved to cut off Huawei’s access to semiconductor chips built with U.S. technology—a critical component of smartphone manufacturing which China to date lags behind in domestic production capacity. Unable to beat Huawei in the race to 5G, the U.S. has turned to diplomatic brute force to extricate the Chinese brand from entire swaths of the global market.

The U.S. has cast China’s tech ascension in highly racialized, politicized terms, casting Huawei, TikTok, and other Chinese corporations as “tentacles of the Chinese Communist Party,” in the words of Mike Pompeo. Calling for an “awakening” of the so-called free world to the imminent threat of China, Pompeo warned that “doing business with a CCP-backed company is not the same as doing business with, say, a Canadian company.” Peter Navarro put the threat of Chinese invasion in even more intimate terms, decrying the fact that “the mothers of America have to worry about whether the Chinese Communist Party knows where their children are."

Under the New Cold War on China, Chinese companies, products, and even overseas students are all potential proxies for Communist Party infiltration of “national security” and the American family itself.

The stakes of U.S.-led efforts to thwart Chinese tech self-sufficiency are clear. Even beyond China’s own economic development programs, Chinese technological advancement has historically delivered real benefits to other Global South allies similarly shunned and sanctioned under the U.S. regime. Huawei itself came under imperial fire for helping to build the DPRK’s wireless infrastructure, which previously struggled to find international sponsors, and has played a similar role in updating Cuba’s telecommunications infrastructure. Meanwhile, Chinese innovations in cryptocurrency could have historic significance in breaking the hegemony of U.S. dollar diplomacy and aid sanctioned nations cut off from using the USD in international transactions to access international financial markets. The oft-forgotten fact that Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou’s arrest in Canada was prompted by alleged violations of U.S. sanctions on Iran is yet another example of the ways Chinese technological ascendance runs counter to the enforcement of U.S. imperial hegemony.

Despite the popular image of gleaming Chinese skylines and unprecedented steps towards eradicating poverty, China remains in many ways a developing country, with a GDP per capita closer to that of Mexico and Thailand than the U.S. or Germany. Technological innovation plays a crucial role in China’s ambitions to grow into a high-income nation, resolve urban-rural inequality, and meet the growing material needs of its people. The age of steel furnaces has given way to the age of semiconductors, but advancing the means of China’s industrial production remains the cornerstone of economic and social advancement under the CPC.

The Trump Administration’s forced sale of TikTok is merely the latest in a longstanding agenda to thwart China’s modernization. Under the digital containment doctrine, the world’s supposed enforcer of free trade and fair competition has revealed itself as a belligerent gatekeeper, foreclosing China’s market access wherever and however it can.

[premium_newsticker id="211406"]

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of The Greanville Post

YOU ARE FREE TO REPRODUCE THIS ARTICLE PROVIDED YOU GIVE PROPER CREDIT TO THE GREANVILLE POST

VIA A BACK LIVE LINK.