STEPHEN COOPER

comparitech

Syria is a patchwork of religions, and religious adherents can easily be incited to violence and revenge by a missing word in a social media post. So, the government is nervous about the Web’s potential to create offense or organize a protest. However, social media is allowed. Many of the attacks on dissenters and journalists in the country are committed by the Turkish authorities that control the north of the country or the Suni rebels who dominate rural areas.

The controls implemented by the Syrian government are less threatening than the murders and torture committed by its opponents – that fact is rarely reported in the West.

Internet penetration and availability

DataReportal by Hootsuite reports that Syria had 8.41 million internet users out of a total population of about 17.88 million in January 2021. That gives an internet penetration rate of about 47 percent. However, the number of users increased by 3.7 percent in January 2021, which was about the same pace as the increase in the general population, so the internet penetration rate hasn’t improved over the last year.

DataReportal by Hootsuite reports that Syria had 8.41 million internet users out of a total population of about 17.88 million in January 2021. That gives an internet penetration rate of about 47 percent. However, the number of users increased by 3.7 percent in January 2021, which was about the same pace as the increase in the general population, so the internet penetration rate hasn’t improved over the last year.

For comparison, the internet penetration rate in neighboring Israel is 88 percent. In Lebanon, it is 76.2 percent. In Iraq, it is 75 percent, In Jordan, it is 66.8 percent. And in Turkey, it is 77.7 percent. So, internet usage is considerably lower in Syria than in the other countries in its region.

According to calculations made by Cable.co.uk in July 2020, Syria has the second-cheapest internet services in the world. Only Ukraine has a lower average price for Broadband internet with a cost of $6.41 per month – the average price in Syria is $6.69 per month. Therefore, the lowest price for internet in Syria is $2.13 per month.

The average household income in Syria, expressed in US dollars, has eroded considerably over the past decade. In 2011, the average monthly wage in the country was 20,000 Syrian Pounds, which was the equivalent of $400. By 2019, the monthly salary had doubled to 40,000 Syrian Pounds, but the dollar value of that amount had fallen to $55. So, the poor exchange rate explains why internet services seem so cheap when expressed in US Dollars.

Those Syrians who can’t afford internet service at home or on a mobile device can use free WiFi hotspots in public spaces and privately run hospitality establishments, such as cafés. There are just under 66,000 free WiFi hotspots in Syria. Of those, 6,400 are in the capital Damascus, according to WiFi Maps. This compares to 45,000 free hotspots in Lebanon and 16,000 in Jordan. In addition, WiFi Maps reports that there are currently 381,622 free WiFi hotspots in Iraq.

Internet speeds in Syria

The online internet speed testing service, Ookla compiles a tally of the average internet speeds in 180 countries. It produces the Ookla Speedtest Global Index, updated each month, and gives average speeds for fixed-line and mobile internet services in each country.

The fixed-line internet services in Syria put the country in 170th place with an average download speed of 10.28 Mbps. Ookla only includes 139 countries in its mobile speeds survey, and Syria comes 105th in that list, with an average download speed of 22.39 Mbps. Those figures were recorded in July 2021.

For comparisons, the global average speeds in July 2021 measured by Ookla were 107.5 Mbps for fixed-line services and 55.07 Mbps for mobile internet. The top of the mobile internet speed table was the UAE with 190.03 Mbps, and the country with the fastest average speed for fixed-line services was Monaco with 256.7 Mbps. The USA is 14th in both of those tables, with an average speed of 195.55 Mbps for fixed-line services and 91.02 Mbps for mobile internet. Israel is 54th in the mobile internet speeds table with 46.3 Mbps and 22nd in the fixed-line speed list with 168.23 Mbps.

Digital awareness

There is a lack of cybersecurity awareness in Syria, which is surprising, given that the country is in a state of conflict.

The lack of interest by Syria’s government in promoting a cybersecurity policy to businesses and public sector agencies probably lies with the nature of those who oppose the government with the most vigor – they are fundamentalists who condemn the use of technology. So, even a half-hearted approach to cybersecurity puts government agencies way ahead of its leading detractors, whose lack of interest in technology means they are unlikely to attack by that channel.

According to Edward Snowden, the country experienced a significant shock in 2013 and 2014 when the internet was cut off in Syria several times by the US’s NSA in support of Syrian rebels. However, several service suspensions, including blackouts that affected mobile phone services, are judged to have been implemented by the government for convenience when launching attacks on the rebels.

The government successfully foisted the blame for those actions on the rebels themselves, which seems to have discouraged the US security services from attacking the telecommunications infrastructure of Syria again. Rather than undermining confidence in the government, internet suspensions sapped support for the rebels, so infrastructure attacks have not reoccurred since 2014.

The primary threat to internet availability in Syria is infrastructure damage and the unreliability of the electricity supply. The northern sector of the country is cut off from government-controlled infrastructure, and Turkish companies supply internet access. The Turkish government tends to shut down the internet in the areas of Syria that it controls. Around their power base in Idlib, the rebels violently discourage the use of the internet and destroy much of the telecommunications infrastructure in their realm.

Online anonymity

Despite being constantly under attack, the government of Syria doesn’t put obstacles in the way of the general public getting access to the internet. Most internet service providers are privately run, and there is no requirement for government approval to get fixed-line internet service, a mobile phone, or a mobile data plan. If anything, the Syrian government is probably guilty of being a bit too lax over enforcing identity checks for SIM cards. As a result, mobile broadband penetration in Syria is very low at about 15 percent of the population. However, 3G coverage, which makes mobile internet possible, is available in 85 percent of Syrian territory.

Access to privacy tools

VPNs are legal in Syria, as are encrypted chat apps, such as Signal, Telegram, and WhatsApp. In October 2018, the Syrian Telecommunications and Post Regulatory Authority (SY-TPRA) revealed that it was considering a ban on VoIP services. This was mainly because the free international voice and video call these services offered undermined the state-owned telecoms provider, Syrian Telecom. However, that ban was never implemented.

The Syrian government doesn’t block access to websites advertising VPN services or explaining how they work. This is in stark contrast to other Middle Eastern countries with less of a reputation for repression, such as Egypt, where VPN websites are the main target of government bans. The UK implements blocks on VPN website access through DNS sinkholing, unofficially implemented by ISPs; the Syrian government doesn’t.

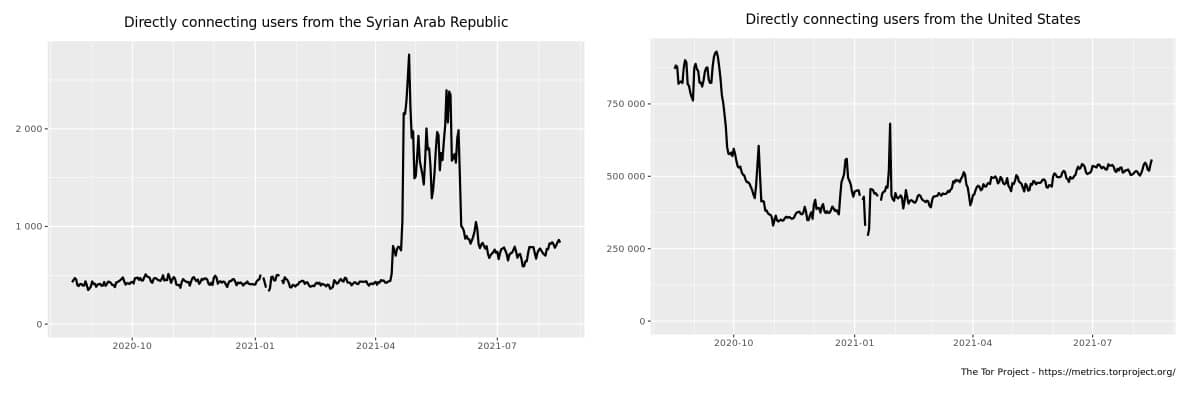

The Tor browser, a free private network similar to a VPN, is active in Syria and easy to access. However, it is not widely used because not many people know about it. The graph below shows the number of users per day in Syria from August 2020 to August 2021.

Up until early April 2021, the number of daily users of Tor was around 500. From April through to June, Tor activity was much higher, reaching towards 2,500 daily users. However, this could be due to the actions of journalists from overseas reporting within Syria on the Presidential election. Such an event generally attracts an influx of news media, and those organizations routinely use Tor to file reports from locations with a reputation for surveillance.

Alongside the graph for Tor usage in Syria, you can see the equivalent activity in the USA during the same period. Take a note of the axis values of this graph. It shows that the Tor usage rate was around 500,000 daily users in the USA during the period.

Cybercrime: prevalence and attack types

Like many countries in the world, Syria has legislation against cybercrime. The central plank of anti-cyber terrorism legislation is the Cybercrime Law 17/2012, updated in 2018. This law established the responsibility for monitoring cybercrimes in Syria and assigned it to the National Agency for Network Services (NANS). This responsibility is implemented by CERT Syria, which is the national Computer Emergency Response Team.

The 2018 amendment to the law required a cadre of judges in the intricacies of technology. This addressed a lack of comprehension of technical issues that previously made the judiciary incapable of properly adjudicating cybercrime cases.

The need for updated processes to combat cybercrime originates with a hacker team called the Syrian Electronic Army. This group is the main threat to internet security in Syria. However, their activities are sporadic, and the group has fallen dormant for long periods.

The Syrian Electronic Army has often been labeled by anti-Assad activists, writing from Western nations, as a branch of the Syrian government. However, no one has ever come up with any proof of a link.

The SEA was particularly active from its creation in 2011 to 2014, but it didn’t pose much of a threat within Syria during that phase – its targets were mainly in the USA. Rather than being a criminal operation, the SEA is an activist group, not unlike Anonymous in the USA. The group certainly supports the Syrian government, and its targets are usually those who oppose the government. However, this does not automatically prove that the government directs the group.

The group disappeared but re-emerged in December 2018 with a specific type of attack that used malware to infect Android mobile devices. This phase of attack has re-emerged recently in the guise of a fake Covid app. The hackers use a spyware system called SilverHawk that enables the theft of data from the phone or even controls the camera and the microphone.

Blocked content

The Syrian government blocked Facebook from 2007 to 2011, and YouTube was also banned. [As tools of Washington's hybrid wars, both are major purveyors of Western imperialist propaganda. —Ed]

All of the major social media platforms are available in Syria, as are Telegram, WhatsApp, and Skype. Despite claims of government censorship, these platforms have been used on several occasions to highlight injustices, raise campaigns against corruption, and make demands on the government. Despite these anti-government uses for these platforms, they have not been shut down.

Netflix is not available in Syria. However, rather than this being a ban on Netflix imposed by the Syrian government, this is a ban on Syria imposed by Netflix. Syria is one of only two countries in the world in which Netflix refuses to stream its content – the other is North Korea. The video service also isn’t available in the Crimea region of Ukraine/Russia.

Reporting on Syrian internet freedoms

There are two critical pieces of advice concerning Syria:

- Don’t go there

- Don’t believe everything you read about the country

Syria is a complicated tangle of religions, and for centuries, the citizens of the country have learned to co-exist by avoiding criticisms of other people’s practices.

The lack of criticism of government policy visible day-to-day on social media in Syria is depicted in Western media as “self-censorship,” implying that Syrians are too afraid to speak freely. However, the frequent use of social media for mass protests shows that people are not scared – they just don’t want to rock the boat over religion because they know that if the rebels seize power, things will get a lot worse.

Western pressure groups make much of the 2018 legal reform in Syria because it includes a three-year criminal sentence for hate speech or the encouragements of criminal acts. However, laws against hate speech and illegal online activities are common in the USA and Europe, so why shouldn’t they exist in Syria?

The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of The Greanville Post. However, we do think they are important enough to be transmitted to a wider audience.

All image captions, pull quotes, appendices, etc. by the editors not the authors.

YOU ARE FREE TO REPRODUCE THIS ARTICLE PROVIDED YOU GIVE PROPER CREDIT TO THE GREANVILLE POST VIA A BACK LIVE LINK.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

[premium_newsticker id=”211406″]

Don’t forget to sign up for our FREE bulletin. Get The Greanville Post in your mailbox every few days.