The leader’s unshakeable ambition is that China’s renaissance will smash memories of the ‘century of humiliation’ once and for all

Marx. Lenin. Mao. Deng. Xi.

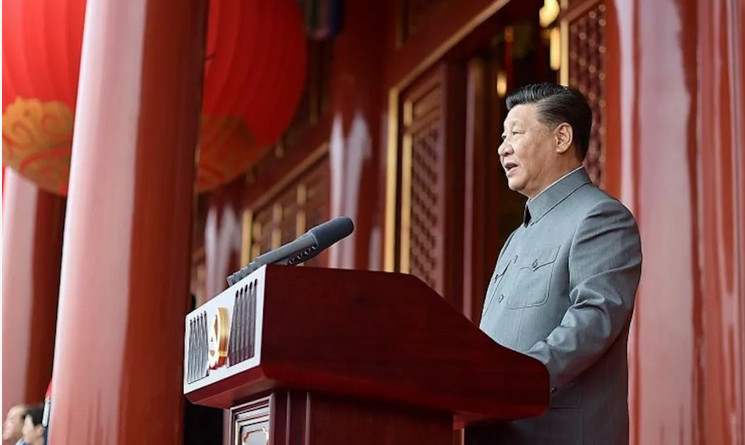

Late last week in Beijing, the sixth plenum of the Chinese Communist Party adopted a historic resolution – only the third in its 100-year history – detailing major accomplishments and laying out a vision for the future.

Essentially, the resolution poses three questions. How did we get here? How come we were so successful? And what have we learned to make these successes long-lasting?

The importance of this resolution should not be underestimated. It imprints a major geopolitical fact: China is back. Big time. And doing it their way. No amount of fear and loathing deployed by the declining hegemon will alter this path.

The resolution will inevitably prompt quite a few misunderstandings. So allow me a little deconstruction, from the point of view of a gwailo who has lived between East and West for the past 27 years.

If we compare China’s 31 provinces with the 214 sovereign states that compose the “international community”, every Chinese region has experienced the fastest economic growth rates in the world.

Across the West, the lineaments of China’s notorious growth equation – without any historical parallel – have usually assumed the mantle of an unsolvable mystery.

Little Helmsman Deng Xiaoping’s ’s famous “crossing the river while feeling the stones”, described as the path to build “socialism with Chinese characteristics” may be the overarching vision. But the devil has always been in the details: how the Chinese applied – with a mix of prudence and audaciousness – every possible device to facilitate the transition towards a modern economy.

The – hybrid – result has been defined by a delightful oxymoron: “communist market economy.” Actually, that’s the perfect practical translation of Deng’s legendary “it doesn’t matter the color of the cat, as long as it catches mice.” And it was this oxymoron, in fact, that the new resolution passed in Beijing celebrated last week.

Made in China 2025

Mao and Deng have been exhaustively analyzed over the years. Let’s focus here on Papa Xi’s brand new bag.

Right after he was elevated to the apex of the party, Xi defined his unambiguous master plan: to accomplish the “Chinese dream”, or China’s “renaissance.” In this case, in political economy terms, “renaissance” meant to realign China to its rightful place in a history spanning at least three millennia: right at the center. Middle Kingdom, indeed.

Already during his first term Xi managed to imprint a new ideological framework. The Party – as in centralized power – should lead the economy towards what was rebranded as “the new era.” A reductionist formulation would be The State Strikes Back. In fact, it was way more complicated.

This was not merely a rehash of state-run economy standards. Nothing to do with a Maoist structure capturing large swathes of the economy. Xi embarked in what we could sum up as a quite original form of authoritarian state capitalism – where the state is simultaneously an actor and the arbiter of economic life.

Team Xi did learn a lot of lessons from the West, using mechanisms of regulation and supervision to check, for instance, the shadow banking sphere. Macroeconomically, the expansion of public debt in China was contained, and the extension of credit better supervised. It took only a few years for Beijing to be convinced that major financial sphere risks were under control.

China’s new economic groove was de facto announced in 2015 via “Made in China 2025”, reflecting the centralized ambition of reinforcing the civilization-state’s economic and technological independence. That would imply a serious reform of somewhat inefficient public companies – as some had become states within the state.

In tandem, there was a redesign of the “decisive role of the market” – with the emphasis that new riches would have to be at the disposal of China’s renaissance as its strategic interests – defined, of course, by the party.

So the new arrangement amounted to imprinting a “culture of results” into the public sector while associating the private sector to the pursuit of an overarching national ambition. How to pull it off? By facilitating the party’s role as general director and encouraging public-private partnerships.

The Chinese state disposes of immense means and resources that fit its ambition. Beijing made sure that these resources would be available for those companies that perfectly understood they were on a mission: to contribute to the advent of a “new era.”

Manual for power projection

There’s no question that China under Xi, in eight short years, was deeply transformed. Whatever the liberal West makes of it – hysteria about neo-Maoism included – from a Chinese point of view that’s absolutely irrelevant, and won’t derail the process.

What must be understood, by both the Global North and South, is the conceptual framework of the “Chinese dream”: Xi’s unshakeable ambition is that the renaissance of China will finally smash the memories of the “century of humiliation” for good.

Party discipline – the Chinese way – is really something to behold. The CCP is the only communist party on the planet that thanks to Deng has discovered the secret of amassing wealth.

And that brings us to Xi’s role enshrined as a great transformer, on the same conceptual level as Mao and Deng. He fully grasped how the state and the party created wealth: the next step is to use the party and wealth as instruments to be put at the service of China’s renaissance.

Nothing, not even a nuclear war, will deviate Xi and the Beijing leadership from this path. They even devised a mechanism – and a slogan – for the new power projection: the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), originally One Belt, One Road (OBOR).

In 2017, BRI was incorporated into the party statutes. Even considering the “lost in translation” angle, there’s no Westernized, linear definition for BRI.

BRI is deployed on many superimposed levels. It started with a series of investments facilitating the supply of commodities to China.

Then came investments in transport and connectivity infrastructure, with all their nodes and hubs such as Khorgos, at the Chinese-Kazakh border. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), announced in 2013, symbolized the symbiosis of these two investment paths.

The next step was to transform logistical hubs into integrated economic zones – for instance as in HP based in Chongjing exporting its products via a BRI rail network to the Netherlands. Then came the Digital Silk Roads – from 5G to AI – and the Covid-linked Health Silk Roads.

What’s certain is that all these roads lead to Beijing. They work as much as economic corridors as soft power avenues, “selling” the Chinese way especially across the Global South.

Make Trade, Not War

Make Trade, Not War: that would be the motto of a Pax Sinica under Xi. The crucial aspect is that Beijing does not aim to replace Pax Americana, which always relied on the Pentagon’s variant of gunboat diplomacy.

The declaration subtly reinforced that Beijing is not interested in becoming a new hegemon. What matters above all is to remove any possible constraints that the outside world may impose over its own internal decisions, and especially over its unique political setup.

The West may embark on hysteria fits over anything – from Tibet and Hong Kong to Xinjiang and Taiwan. It won’t change a thing.

Concisely, this is how “socialism with Chinese characteristics” – a unique, always mutant economic system – arrived at the Covid-linked techno-feudalist era. But no one knows how long the system will last, and in which mutant form.

Corruption, debt – which tripled in ten years – political infighting – none of that has disappeared in China. To reach 5% annual growth, China would have to recover the growth in productivity comparable to those breakneck times in the 80s and 90s, but that will not happen because a decrease in growth is accompanied by a parallel decrease in productivity.

A final note on terminology. The CCP is always extremely precise. Xi’s two predecessors espoused “perspectives” or “visions.” Deng wrote “theory.” But only Mao was accredited with “thought.” The “new era” has now seen Xi, for all practical purposes, elevated to the status of “thought” – and part of the civilization-state’s constitution.

That’s why the party resolution last week in Beijing could be interpreted as the New Communist Manifesto. And its main author is, without a shadow of a doubt, Xi Jinping. Whether the manifesto will be the ideal road map for a wealthier, more educated and infinitely more complex society than in the times of Deng, all bets are off.

Pepe Escobar is a Brazilian journalist and international policy analyst whose column "The Roving Eye" for Asia Times Online regularly discusses the multi-national "competition for dominance over the Middle East and Central Asia." Escobar is also a frequent commentator on Russia's RT and Sputnik News, telling The New Republic in 2012 that he was not troubled by its Russian sponsorship: I knew the Kremlin involvement, but I said, why not use it? After a few months, I was very impressed by the American audience.

ADDENDUM

Xi Jinping's Manifesto:

The sixth plenary session of the 19th Communist Party of China Central Committee:

The meeting announced the upcoming publication of the following paper by Xi that Pepe Escobar and others are calling Xi's New Communist Manifesto. I'm leaving the machine translation completely intact, so nothing will be capitalized, nor will any grammatical errors be resolved. It will be curious to compare its English version which I expect to be published at some future time. insist on arming the whole party with Marxism and its theory of chinese innovation※ xi jinping one on the way forward, we must strengthen the theoretical armed forces of the whole party, in accordance with the requirements of building a Marxist learning party, deeply study and master Marxism-leninism, mao zedong thought, in-depth study and master the theoretical system of socialism with chinese characteristics, and firmly establish dialectical materialism and historical materialism world view and methodology. (speech at the 18th plenary session of the 18th central committee of the communist party of china on november 15, 2012) two first of all, we must seriously study Marxist theory, which is our ability to do all the work of the watcher, but also the leading cadres must generally master the ability of the work to win the watcher skills. comrade mao zedong once suggested that "if our party had learned Marxist-leninist comrades systematically rather than piecemeal, practically rather than hollowly, it would greatly enhance the fighting power of our party". this task is still very realistic before our party today. only by learning Marxism-leninism, mao zedong thought, deng xiaoping theory, the important thought of "three represents" and the scientific concept of development, especially understanding the Marxist positions, views and methods that run through it, can we have a clear understanding and accurate grasp of the ruling law of the communist party, the law of socialist construction and the law of human social development, can we always firmly believe in ideals, adhere to scientific guiding ideology and correct direction in the complex situation, and can we lead the people down the right path. in order to push forward socialism with chinese characteristics. (speech at the 80th anniversary celebration conference of the central party school on march 1, 2013 and the opening ceremony of the spring semester in 2013) three in order to refine the "king kong is not a bad body", we must arm the mind with scientific theory and constantly cultivate our spiritual home. for leading cadres, especially senior cadres, it is necessary to master the basic theory of Marxism systematically as a watcher's skill. the famous scholar kingdom wei discusses three realms of discipline: one is "last night the west wind withered blue trees, alone on the high-rise, looking at the end of the world"; leading cadres should also have these three realms of learning theory. first of all, theoretical learning should have the "hope for the end of the world" as ambitious pursuit, endure the "last night the west wind withering blue tree" of the cold and "only high-rise" loneliness, quiet to read through; hard work, fine kung fu, even if the "belt gradually wide" also "ultimately unrepentant", "people" also willingly; "looking back", in the "light and fire" to understand the true meaning. (address at the national conference on propaganda and thought work, 19 august 2013) four theoretical cultivation is the core of the comprehensive quality of cadres, theoretical maturity is the basis of political maturity, political firmness stems from theoretical sobriety. in a certain sense, mastering the depth of Marxist theory determines the degree of political sensitivity, the breadth of thinking vision and the height of ideological realm. therefore, i ask the politburo to study collectively to strengthen the study of the basic principles of Marxism, and has arranged to study the contents of historical materialism, dialectical materialism, Marxist political economy, and later. we should maintain strong theoretical interest, consciously strengthen the study of Marxist basic theory, calm down to study the original works of marx, Engels, lenin and chairman mao, study the theoretical system of socialism with chinese characteristics, and learn the achievements of the party's theory and line policy innovation since the 18th national congress of the party, and constantly gain and improve. (speech at the "three stricts and three reals" special democratic life meeting of the 18th political bureau of the cpc central committee on december 28, 2015) five the times are the mother of thought, and practice is the source of theory. the development of practice is never-ending, and we know the truth and innovate theory. today, the changes of the times and the breadth and depth of china's development far exceeded the imagination of Marxist classic writers at that time. at the same time, china's socialism only a few decades of practice, is still in the primary stage, the more the development of the cause of new situations and new problems, but also the more we need to boldly explore in practice, in theory and constantly break through. if it is not thorough in theory, it is difficult to convince people. we should examine the realistic basis and practical needs of Marxism in contemporary development with a broader perspective, adhere to the problem orientation, take what we are doing as the center, listen to the voice of the times, promote the combination of Marxism with the concrete reality of contemporary china's development in a deeper way, and constantly open up a new realm of Marxism development in the 21st century, so that contemporary chinese Marxism radiates a more brilliant light of truth. (speech at the general assembly to celebrate the 95th anniversary of the founding of the communist party of china on july 1, 2016) six times are changing and society is developing, but the basic principles of Marxism are still scientific truths. although our times have undergone great and profound changes compared with marx's, we are still in the historical era indicated by Marxism from the perspective of the 500-year-old socialism of the world. this is the scientific basis for us to maintain firm confidence in Marxism and to maintain a winning belief in socialism. Marxism is the fundamental of the great tree of the continuous development of our party and the people's cause, and it is the source of the long river that our party and the people continue to forge ahead. if we deviate from or abandon Marxism, our party will lose its soul and lose its way. on the fundamental issue of adhering to Marxism as a guide, we must remain steadfast and must not waver under any circumstances. (speech at the 43rd collective learning session of the 18th political bureau of the cpc central committee on september 29, 2017) seven looking back on the party's struggle, we can find that the reason why our party has been able to continue to go through hardships and hardships to create new glory, it is very important that our party always attach importance to the ideological construction of the party, the theory of strong party, adhere to the scientific theory to arm the minds of the vast number of party members and cadres, so that the whole party has always maintained a unified thinking, firm will, strong fighting power. if we want to win advantages, win initiatives, win the future, overcome all kinds of roadblocks and stumbling blocks along the way, we must take Marxism as a watcher's skill, think about and grasp a series of major problems facing future development with a broader vision and a longer-term perspective, continuously improve the ability of the whole party to analyze and solve practical problems using Marxism, and continuously improve our ability to use scientific theories to guide us to meet major challenges, resist major risks, overcome major obstacles and resolve major contradictions. we should persist in arming our minds and gathering our souls with the latest achievements of the chineseization of Marxism, firm the party's Marxist beliefs and communist ideals, and continuously improve the theoretical thinking ability and ideological and political level of the whole party, especially the leading cadres. (speech at the 43rd collective learning session of the 18th political bureau of the cpc central committee on september 29, 2017) eight since the 18th national congress, changes in the situation at home and abroad and the development of various undertakings in china have raised a major issue of the times for us, that is, we must systematically answer the basic questions of what kind of socialism with chinese characteristics will adhere to and develop in the new era, how to adhere to and develop socialism with chinese characteristics, including the general goal, overall task, overall layout, strategic layout and development direction, development mode, development momentum, strategic steps, external conditions and political guarantees in the new era. and according to the new practice, we should make theoretical analysis and policy guidance on economy, politics, rule of law, science and technology, culture, education, people's livelihood, nationality, religion, society, ecological civilization, national security, national defense and army, "one country, two systems" and the reunification of the motherland, united front, diplomacy and party construction, so as to better adhere to and develop socialism with chinese characteristics. around this important topic of the times, our party adheres to Marxism-leninism, mao zedong thought, deng xiaoping theory, the important thought of the "three represents" and the scientific concept of development as the guide, adheres to emancipating the mind, seeking truth from facts, advancing with the times, seeking truth and pragmatism, adheres to dialectical materialism and historical materialism, closely combines the new conditions of the times and practical requirements, deepens the understanding of the ruling law of the communist party, the law of socialist construction, the law of human social development with a new perspective, and makes arduous theoretical explorations. major theoretical innovations have been achieved, forming a new era of socialist ideology with chinese characteristics. (reporting at the 19th national congress of the communist party of china on october 18, 2017) nine the new era of socialism with chinese characteristics is the inheritance and development of Marxism-leninism, mao zedong thought, deng xiaoping theory, the important thought of the "three represents", the scientific concept of development, the latest achievement of Marxism in china, the crystallization of the party and the people's practical experience and collective wisdom, an important part of the theoretical system of socialism with chinese characteristics, and a guide for the whole party and the people to strive for the great rejuvenation of the chinese nation. (reporting at the 19th national congress of the communist party of china on october 18, 2017) ten we will fully implement the socialist ideology and basic strategy of socialism with chinese characteristics in the new era and continuously improve the level of the party's Marxist theory. the thought and basic strategy of socialism with chinese characteristics in the new era are not falling from the sky, not subjectively imagined, but the wisdom of the innovation and creation of the whole party and the people of all ethnic groups since the founding of new china, especially since the reform and opening-up, on the basis of our party's theoretical innovation and practical innovation. the tree of life is evergreen. the source of a theory can only be rich and vivid real life, and the motive force can only be the realistic requirement to solve social contradictions and problems. on the journey of the new era, all party comrades must carry forward the theory and practice, closely link the historical changes that have taken place in the cause of the party and the state, closely link the new reality of socialism with chinese characteristics into a new era, closely link the major changes in the major contradictions of our society, closely link the "two hundred years" goal and tasks, consciously use theory to guide practice, make all aspects of work more in line with the requirements of objective laws, scientific laws, and continuously improve the ability of the new era to adhere to and develop socialism with chinese characteristics. turn the party's scientific theory into a powerful force dedicated to the realization of the "two hundred years" goal and the great rejuvenation of the chinese dream of the chinese nation. (speech at the 19th plenary session of the 19th central committee of the communist party of china on october 25, 2017) eleven from the publication of the communist manifesto to today, 170 years have passed, human society has undergone tremendous changes, but the general principles expounded by Marxism are still completely correct in general. we should adhere to and apply dialectical materialism and historical materialism world view and methodology, adhere to and apply Marxist positions, viewpoints and methods, adhere to and apply Marxism on the materiality of the world and its development law, on the nature, history and related laws of human social development, on the law of human liberation and free all-round development, on the nature of understanding and its development law and other principles, adhere to and apply the Marxist view of practice, mass view, class view, development view, contradiction. really put Marxism as a watcher's skill to understand and use well. (address at the general assembly to mark the 200th anniversary of marx's birth on 4 may 2018) twelve there must be a scientific attitude towards scientific theories. Engels pointed out profoundly: "Marx's view of the whole world is not a doctrine, but a method." it provides not ready-made dogmas, but the starting point for further research and methods for such research. Engels also points out that our theory "is a product of history, with completely different forms and completely different contents at different times". the basic principles of scientific socialism cannot be lost, they are not socialism. at the same time, scientific socialism is by no means a fixed dogma. as i said, the great social changes in contemporary china are not simply a continuation of the master of our history and culture, a template for the classical Marxist writers, a reprint of socialist practice in other countries, or a replica of the modernization of foreign countries. socialism is not set in one, unchanging way, only the basic principles of scientific socialism and the country's specific reality, historical and cultural traditions, the requirements of the times closely combined, in practice, and constantly explore the summary, in order to turn the blueprint into a beautiful reality. (address at the general assembly to mark the 200th anniversary of marx's birth on 4 may 2018) thirteen the vitality of theory lies in continuous innovation, and it is the sacred duty of the chinese communists to promote the continuous development of Marxism. we should persist in observing the times with Marxism, interpreting the times, leading the times, promoting the development of Marxism with the vivid and rich practice of contemporary china, absorbing all the outstanding achievements of civilization created by mankind with a broad vision, persisting in the reform of keeping new, constantly surpassing ourselves, taking great benefits in the open, constantly improving ourselves, deepening our understanding of the ruling law of the communist party, the law of socialist construction, the law of human social development, and constantly opening up the new realm of Marxism in contemporary china and Marxism in the 21st century. (address at the general assembly to mark the 200th anniversary of marx's birth on 4 may 2018) fourteen it is the historical responsibility of the contemporary chinese communists to develop Marxism in the 21st century and Marxism in contemporary china. we should strengthen the consciousness of problems, the consciousness of the times, the consciousness of strategy, grasp the essence and internal connection of the development of things with profound historical vision and broad international vision, closely track the creative practice of hundreds of millions of people, learn from the absorption of all the outstanding achievements of human civilization, and constantly answer the new major issues raised by the times and practice, so that contemporary chinese Marxism radiates a more brilliant light of truth. (speech at the conference to celebrate the 40th anniversary of reform and opening-up on december 18, 2018) fifteen leading cadres should strengthen theoretical cultivation, deeply study the basic theory of Marxism, learn to understand the new era of socialism with chinese characteristics, master the dialectical materialism world view and methodology that runs through it, improve strategic thinking, historical thinking, dialectical thinking, innovative thinking, rule of law thinking, bottom line thinking ability, good at grasping the law from the complex contradictions, and constantly accumulate experience and growth talents. (speaking on january 21, 2019 at the opening of a seminar on major risks at the provincial and ministerial levels, leading cadres adhere to the bottom line thinking and focus on preventing and resolving major risks) sixteen in the study theory, cadres should devote their energy to comprehensive systematic learning, timely follow-up learning, in-depth thinking, contact with practical learning. to study the new era of socialism with chinese characteristics, we should deeply understand and understand its significance of the times, theoretical significance, practical significance, world significance, and deeply understand its core meaning, spiritual essence, rich connotation and practical requirements. to closely combine the new practice of the new era, closely combine the idea and work of the actual, targeted focus on learning, think more, learn deeply, know it and know it. the most effective way to learn the theory is to read the original, learn the original text, understand the principle, strong reading strong record, often learn new, go deep, go to the reality, go to the heart, put themselves in, put the responsibility into, put the work into, do learn, think, use through, know, believe, line unity. (speaking at the opening ceremony of the training course for young cadres of the central party school (national school of administration) on march 1, 2019) seventeen for the way of politics, to be the man of the book. the party's cultivation and moral level of cadres will not be raised naturally with the increase of the party's working age, nor will they be naturally improved with the promotion of their posts, and self-cultivation, self-restraint and self-reform must be strengthened. the new era of socialism with chinese characteristics not only contains the important thought of the party's governance, but also runs through the requirements of the chinese communists' political character, value pursuit, spiritual realm and style of conduct. we should cultivate political determination, refine political vision, abide by political rules, consciously do political understanding, honest people. (speaking at the opening ceremony of the training course for young cadres of the central party school (national school of administration) on march 1, 2019) eighteen to carry out this thematic education is an urgent need to arm the whole party with the idea of socialism with chinese characteristics in the new era. Marxism is the fundamental guiding ideology of our party and nation-ed. since its birth, the communist party of china has written Marxism clearly on its own banner. our party has never wavered in its firm belief in Marxism, whether in good times or adversity. since the reform and opening-up, our party has carried out the whole party, "three lectures" education, advanced sex education activities, learning and practice scientific development view activities, mass line education practice activities, and so on, to promote the "two learning and one work" learning education normalization and institutionalization, through the combination of centralized education and regular education, and constantly strengthen the party's theoretical learning, education, armed work. in the new era, our party conforms to the new requirements of the development of the times and creates the new era of socialism with chinese characteristics. every step forward in theoretical innovation, the theoretical armed forces must follow further. at present, some party members and cadres in theoretical learning compared with the requirements of the party central committee there is still a significant gap, did not go deep, go to the heart, go to the real. to carry out this theme education is to adhere to the idea of building the party, the theory of strong party, adhere to the unity of learning and thinking, knowledge and belief, promote the majority of party members and cadres comprehensive systematic learning, in-depth thinking, contact with practical learning, and constantly enhance the "four consciousness", firm "four self-confidence", do "two maintenance", build the foundation of faith, complement the spirit of calcium, put steady thinking rudder. (speech at the "remembering the beginning, remembering the mission" education work conference on 31 may 2019) nineteen in theoretical learning, one is to consciously take the initiative to learn. central and state organs have a lot of work to do, relying only on work time to concentrate on learning is not enough, we must strengthen the self-consciousness of learning, enhance the endogenous motivation of learning, use spare time to study hard. baht accumulation, the day will be month, in order to water into the canal, integration. the second is to follow up on the study in a timely manner. the cpc central committee to make new decisions to deploy, the introduction of new documents, we must learn to understand the first time, to develop the people's daily newspaper reports and important comments, watch cctv news broadcast, read the "seek truth" magazine habits, online and offline synchronous learning, so that learning follow-up, understanding follow-up, action follow-up. the third is to contact the actual study. to carry forward the theory and practice, closely link ideas and work practice, to study and solve problems as the focus of learning, must not sit and talk, empty. the fourth is to believe in the practice of learning. to learn and believe, from gradual understanding to epiphany, master the Marxist position and viewpoint methods, learn firm faith, learn the mission to assume. to learn to do, learn to use, physical, the results of learning to do their jobs, promote the development of the cause. (speech at the party building work conference of the central and state organs on july 9, 2019) twenty without forgetting the original heart and keeping in mind the mission, we must unify our thoughts, our will and our actions with the latest achievements of Marxism in china. the advanced nature of Marxist political parties is first embodied in the advanced nature of ideological theory. paying attention to ideological construction and theoretical strength of the party is the distinctive characteristic and glorious tradition of our party. comrade mao zedong once said, "mastering ideological education is the central link in uniting the whole party in the great political struggle." "the communists' initial heart comes not only from the simple feelings of the people, the persistent pursuit of truth, but also from the scientific theory of Marxism. only by adhering to the idea of building the party, the theory of strong party, do not forget the original heart can be more self-conscious, to assume the mission can be more determined. (speech at the education summary conference on the theme "remembering the first heart, remembering the mission" on 8 january 2020) twenty-one every step forward in theoretical innovation, the theoretical armed forces must follow further. the party's previous concentrated educational activities have led with ideological education, focusing on solving the problems of learning is not in-depth, ideological unity, and action can not keep up, both hard and concentrated efforts to promote ideological unity, political unity and unity of action of the whole party. we should make learning and carrying out the party's innovative theory the top priority of ideological arming, connect with learning the basic principles of Marxism, combine with studying the history of the party, the history of new china, the history of reform and opening-up, and the history of socialist development, and link it with the rich practice of our great struggle, building great projects, advancing great undertakings and realizing great dreams in the new era. (speech at the education summary conference on the theme "remembering the first heart, remembering the mission" on 8 january 2020) twenty-two in theory, firm sobriety is the premise of ideological and political firm sobriety, and scientific theory is the foundation of firm ideal belief. the whole party must establish a system that does not forget the original heart and keeps in mind its mission, constantly arm the whole party with the new era of socialist ideology with chinese characteristics, educate the people and guide the work, promote the institutionalization of learning and education, and constantly firmly build the ideal belief of the chinese dream. (speech at the fourth plenary session of the 19th central commission for discipline inspection of the communist party of china on january 13, 2020) twenty-three we should arm the whole party with the party's scientific theory. organization is "shape" and thought is "soul". to strengthen the party's organizational construction, we should not only "shape" but also "cast soul". the reason why our party has been able to accomplish the arduous task that all kinds of political forces can't accomplish since modern times, and to lead the people to the brilliant achievements of revolution, construction and reform, lies in always taking Marxism as a guide to action, always arming the whole party with the latest achievements of Marxism in china, so that the whole party will always maintain a unified thought, firm will, coordinated action and strong fighting power. (speech at the 21st collective learning session of the 19th political bureau of the cpc central committee on june 29, 2020) twenty-four the vitality of theory lies in innovation. Marxism has profoundly changed china, and china has greatly enriched Marxism. over the past hundred years, our party has adhered to the unity of emancipating the mind and seeking truth from facts, the unity of the solid foundation of peiyuan and the unity of keeping the truth and innovation, and continuously opened up a new realm of Marxism, which has produced mao zedong thought, deng xiaoping theory, the important thought of the "three represents" and the scientific concept of development, and the new era of socialist thought with chinese characteristics, which has provided scientific theoretical guidance for the development of the party and the people's cause. the history of our party is a history of advancing the chineseization of Marxism, and it is a history of continuously promoting theoretical innovation and theoretical creation. to educate and guide the whole party from the extraordinary course of the party to understand how Marxism has profoundly changed china and changed the world, to understand the truth and practical power of Marxism, to deepen the understanding of the theoretical quality of chinese Marxism, especially in the light of the historical achievements and historic changes in the cause of the party and the state since the 18th national congress of the party, to deeply study and understand the party's innovative theory in the new era, and to persist in arming the mind with the latest achievements of the party's innovative theory, guiding practice, drive the work. (speech at the mobilization conference on learning and education in party history on february 20, 2021) twenty-five in the party history learning education to do the study of history and reason, clear reason is the premise of increasing faith, chongde, force. we should deeply understand the historical logic, theoretical logic and practical logic of the communist party of china, why Marxism is good and why socialism with chinese characteristics is good from the party's brilliant achievements, arduous courses, historical experience and fine tradition. we should deeply understand the historical inevitability of adhering to the leadership of the communist party of china and strengthen our confidence in the leadership of the party. we should deeply understand the truthfulness of Marxism and its theory of chinese innovation, and strengthen the firmness of conscientiously implementing the party's innovation theory. we should deeply understand the correctness of the socialist road with chinese characteristics and unswervingly follow the only correct path of socialism with chinese characteristics. (speech during a visit to fujian from 22 to 25 march 2021) twenty-six Marxist science reveals the law of human social development, points out the way for human beings to seek their own liberation, promotes the process of human civilization, and is a powerful ideological weapon for us to understand and transform the world. this year marks the 100th anniversary of the founding of the communist party of china. since its establishment, the communist party of china has taken Marxism as its guiding ideology, adhered to the basic principles of Marxism and china's concrete reality, and continuously promoted the chineseization, modernization and popularization of Marxism. Marxism has given off a new vitality in china in the 21st century, socialism with chinese characteristics has entered a new era, and the chinese nation has embarked on a new journey of great rejuvenation. (letter from may 27, 2021 to the world seminar on Marxist political parties' theory) twenty-seven the history of our party is a history of promoting the chineseization of Marxism, constantly enriching and developing Marxism, and it is also a history of using Marxist theory to understand and transform china. over the past 100 years, our party has adhered to the combination of the basic principles of Marxism with china's concrete reality, created mao zedong thought and deng xiaoping theory, formed the important thought of "three representatives" and the scientific concept of development, created a new era of socialist thought with chinese characteristics, and guided the party and the people's cause to constantly open up new development. why the communist party of china can, why socialism with chinese characteristics is good, is fundamentally because of Marxism. we should understand the power of truth from the party's 100-year struggle history, deepen our understanding of the ruling law of the communist party, the law of socialist construction and the law of human social development, and shine our way forward with the light of Marxist truth. (speech at the 31st collective learning session of the 19th political bureau of the cpc central committee on june 25, 2021) twenty-eight taking history as a mirror and creating the future, we must continue to promote the chineseization of Marxism. Marxism is the fundamental guiding ideology of our party and nation-ed, and the soul and flag of our party. the communist party of china adheres to the basic principles of Marxism, adheres to seeking truth from facts, starts from china's reality, insights into the trend of the times, grasps the historical initiative, carries out arduous exploration, continuously promotes the chineseization of Marxism, and guides the chinese people to push forward the great social revolution. why can the communist party of china, socialism with chinese characteristics why is good, in the final analysis is because of Marxism! on the new journey, we must adhere to Marxism-leninism, mao zedong thought, deng xiaoping theory, the important thought of "three represents" and the scientific concept of development, fully implement the socialist thought with chinese characteristics in the new era, combine the basic principles of Marxism with china's concrete reality, combine with the excellent traditional chinese culture, observe the times with Marxism, grasp the times, lead the times, and continue to develop contemporary chinese Marxism and Marxism in the 21st century! (speech at the congress to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the founding of the communist party of china on july 1, 2021) this is an excerpt from general secretary xi jinping's speech and letter from november 2012 to july 2021 on the insistence on arming the whole party with Marxism and its theory of chinese innovation. |

The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of The Greanville Post. However, we do think they are important enough to be transmitted to a wider audience.

Don’t forget to sign up for our FREE bulletin. Get The Greanville Post in your mailbox every few days.

YOU ARE FREE TO REPRODUCE THIS ARTICLE PROVIDED YOU GIVE PROPER CREDIT TO THE GREANVILLE POST

VIA A BACK LIVE LINK.