| Editor’s Note: Yes, one more article on Zero Dark Thirty (ZDT). Why? Because it’s a watershed film, but not in the good sense. It marks the moment when Americans (and many clueless audiences around the world, seeing reality in the adulterated fashion American propaganda has taught them) take in torture and the celebration of US imperial military adventures as perfectly normal and in fact entertaining. This is the achievement by which Bigelow and her ilk will be remembered: the frivolization, under a cynical veneer of journalistic impartiality and “art”, of the use of torture and colonialist wars in the defense of a criminal status quo, worldwide. Regarding this critic’s opinion, we find it contains some very perceptive and therefore useful points. We regrettably part ways, however, with his left-liberaloid interpretation of Osama’s (and his ilk’s) motives. Gibney says, “After all, the goal of Osama bin Laden was to provoke Americans to undermine our most fundamental values.” That’s elegant, but also fatuously hackneyed. At best, it’s after the fact wisdom. Very American wisdom, which is not very good when it comes to understanding the world. Osama was moved by much rawer and truer goals. He didn’t care one fig about our freedoms, or “democracy,” or if we all ate one another as long as we left the rest of the world alone, beginning with his beloved Arabic holy lands. But try telling that to officialdom or those whose job it is to keep the main memes of American propaganda on the upswing. Which unfortunately includes far too many liberals. But there’s one more thing. Just about every critic of Bigelow’s is taking her to task as if all that was wrong or mattered with ZDT was the way she presents torture: Did she strike the right balance? Did she go overboard? Is she consciously selling torture? Torture is obviously important, but the broader issue is the seamless blending of Hollywood (and mainstream TV) with imperial propaganda. ZDT is the beginning of a new age.—PG | |

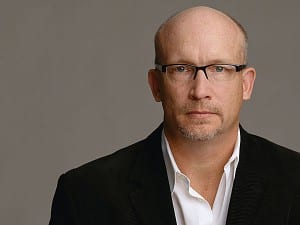

Director Alex Gibney on the dangerous myth perpetuated by the film.

December 21, 2012

It’s difficult for one filmmaker to criticize another. That’s a job best left to critics. However, in the case of Zero Dark Thirty, about the hunt for Osama bin Laden, an issue that is central to the film — torture — is so important that I feel I must say something.

Mark Boal and Kathryn Bigelow have been irresponsible and inaccurate in the way they have treated this issue in their film. I am not alone in that view. Senators Carl Levin, Dianne Feinstein and John McCain wrote a letter to Michael Lynton, the Chairman of Sony Pictures, accusing the studio of misrepresenting the facts and “perpetuating the myth that torture is effective,” and asking for the studio to correct the false impression created by the film. The film conveys the unmistakable conclusion that torture led to the death of bin Laden. That’s wrong and dangerously so, precisely because the film is so well made.

Let me say, as many others have, that the film is a stylistic masterwork, an inspiration in terms of technique from the lighting, camera, acting and viscerally realistic production and costume design. Also, as a screen story, it is admirable for its refusal to funnel the hunt for bin Laden into a series of movie clichés — love interests, David versus Goliath struggles, etc. More than that, the film does an admirable job of showing how complex was the detective work that led to the death of bin Laden: a combination of tips from foreign intelligence, sleuthing through old files, monitoring signals from emails and cell phones (SIGINT) and mining human intelligence on the ground (HUMINT). It’s all the more infuriating therefore, because the film is so attentive to the accuracy of details — including the mechanism of brutal interrogations — that it is so sloppy when it comes to portraying the efficacy of torture. That may seem like a small thing but it is not. Because when we go to war, our politicians will be guided by our popular will. And if we believe that torture “got” bin Laden, then we will be more prone to accept the view that a good “end” can justify brutal “means.”

But torture did not lead us to bin Laden. For other analyses of the way the factual record diverges from Boal/Bigelow version, I recommend pieces by Jane Mayer and Peter Bergen, who are far more experienced journalists than I. In addition, one can also refer to the press release of the Senate Intelligence Committee’s study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, which concludes that, following the examination of more than six million pages of records from the Intelligence Community, the CIA did not obtain its first clues about the identity of bin Laden’s courier from “CIA detainees subjected to coercive interrogation techniques.”

I want to focus my concern on the way in which the film is fundamentally reckless when it comes to the subject of torture. It’s skillful, but not profound. The reason for this is threefold.

1) The very style of the film

Beautifully lit, the film often shot with a handheld camera to emphasize the cinematic urgency of a cinema verite documentary, which lends a false sense of “truthiness” to the narrative. This is one of the reasons I bristled when Mark Boal told Dexter Filkins that he shouldn’t be held responsible for the content of the film because ZD30 is “a movie not a documentary.” Well, if the notion of a documentary is so distasteful, why shoot it like one?

There are other mistakes in that careless remark. It implies that because “movies” (unlike Boal, I would include documentaries, for better and for worse, in that category) have an obligation to entertain, they don’t have to be nitpickers for accuracy. Yet, on the other hand, Bigelow says that this film is a “journalistic account.” So which one is it? You can’t have it both ways. After all, ZD30 is being promoted as a riveting and truthful account of the killing of UBL. Would it be as appealing to viewers if it were “just a movie” about the hunt for fictional terrorist named “Osama bin Bad Guy?”

Every film is faced with the enemy of time. Only so much story can fit into the 90-150 minutes of time that moviegoers are willing to stay in their seats. Naturally, compression is necessary. So are the exclusion and amalgamation of characters so that the viewer does not become bewildered. To paraphrase Werner Herzog, filmmakers don’t need to pursue a bookkeeper’s truth in which every figure is accounted for. Rather they can seek a “poetic truth” is which essential meaning is revealed to viewers. But it’s a cop-out for Boal and Bigelow to say they shouldn’t be held to account for the meaning of their film because “it’s just a movie,” and/or because it’s a “journalistic account.” In the context of the final result, neither statement is credible. When it comes to torture, the film fails the truth test for both accountants and poets.

2) The Truth of the Matter

ZD30 opens in darkness, with the soundtrack haunted by the voices of victims and rescue workers on 9/11. Then the film cuts to a CIA “black site,” where a man named Ammar is being tortured by a CIA agent named Dan (played by Jason Clarke) while another agent, Maya (well acted by Jessica Chastain) looks on. For me, along with the very ending, this was one of the best moments in the film. The juxtaposition of the agony of 9/11 with the payback that followed — waterboarding detainees, walking them around in dog collars (recall Lyndie England) and stuffing them in small plywood boxes — perfectly captured a bitter poetic truth about how members of the Bush Administration responded to tragedy. They built a hard-hearted and soft-headed program of state-sanctioned torture that was likely motivated by revenge, rather than legal precedents, moral principles and well-tested, tough-minded lawful techniques.

So give points to Boal and Bigelow for not pussyfooting around. They make it clear that the CIA tortured people as part of a “detainee program.” But what’s distressing — given that tough-minded beginning — is that the filmmakers don’t ever question the efficacy of torture. We don’t see how corrupting it was, how many mistakes were made. Instead, the narrative engine of Boal’s detective story is kick-started by torture. In the film Dan uses a trick and the implied threat of torture to force “Ammar” to reveal the nickname of bin Laden’s courier, Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti, a man who ultimately helped lead investigators to bin Laden.

Mark Boal has responded to critics by saying that, in the film, the actionable intelligence from Ammar, was obtained “over the civilized setting of a lunch.” But that’s disingenuous. Because the conversation occurs after brutal torture, the implication is that Ammar provides information because he doesn’t want to trade his hummus for a wet washcloth and a sojourn in a plywood box.

“Ammar” is a composite character likely modeled after two characters. The first was probably Hassan Ghul, who was interrogated by the CIA in 2004 with coercive techniques (NOT including waterboarding) and who did provide some details about Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti. But according to Senator Dianne Feinstein (who has access to all of the classified files) all of the vital information was provided prior to the rough stuff. The first clues about al-Kuwaiti were obtained in 2002 through the use of traditional interrogation methods.

The other possible source for the discovery of the name of al-Kuwaiti was Mohammed al-Qahtani, the so-called 20th hijacker, who was captured in Afghanistan and sent to Guantanamo, where he was interrogated first by the FBI and then by the military, who were given special permission by Donald Rumsfeld to use more aggressive techniques set out in the so-called “First Special Interrogation Plan.” According to documents revealed by WikiLeaks, al-Qahtani did mention the name of al-Kuwaiti. But according to the FBI, Al-Qahtani provided all his useful information prior to his “special interrogation.” Al-Qahtani was never waterboarded but he was subjected to a brutal and often bizarre 49-day interrogation at Gitmo, that was documented in logs revealed by Adam Zagorin in Time Magazine. (We portrayed portions of this interrogation in my film, “Taxi to the Dark Side.”)

Many writers have focused on the brutality of the al-Qahtani interrogation. They were right to do so. After all, even Susan Crawford, a Bush Administration official, ultimately admitted that his treatment was, in fact, “torture.” Using techniques loosely based on the CIA’s Kubark Interrogation Manual, and influenced by CIA’s loony new playbook for questioning prisoners in the global war on terror, interrogators kept al-Qahtani from sleeping, force fed him liquids which caused him to urinate on himself and came close to killing him. But what many have overlooked is what happened to the interrogators during the al-Qahtani interrogation. They fell victim to what is called “force drift” (a tendency for interrogators to increase brutality when they don’t get answers) and resorted to increasingly bizarre techniques. What are we to make of the fact that interrogators tried to get al-Qahtani to crack by using authorized “techniques” such as “invasion of space by female”; putting panties on his head, making him wear a “smiley-face” mask (I’m not making this up) and giving him dance lessons; making him watch puppet shows of him having sex with Osama bin Laden, administering forced enemas and making him crawl around like a dog.

The point I’m making is that, when the full history of “Enhanced Interrogation Techniques” is told we will see that it was not only brutal and counterproductive but ridiculous. The CIA waterboarded Abu Zubaydah 83 times and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed 183 times. Considering the repetition, just how effective were those techniques? And how good does the CIA look for insisting on mindless repetition of useless tactics?

But in ZD30, Boal and Bigelow have a problem. In the logic of a “movie,” it’s difficult for viewers root for people who are making terrible mistakes, have become corrupted or who are showcasing needless brutality. As a result, while the filmmakers do showcase American brutality, they suggest that it was necessary. Over and over again, Maya watches DVDs of interrogations using waterboarding and other forms of torture as if these were useful techniques which provided actionable intelligence. She herself uses a fellow operative to be her “muscle,” punching a detainee when she does not get the answer she’s looking for. Absent any other kind of interrogation, viewers of this film must conclude that beating the hell out of people is the only way to get answers. As one detainee says in the film, “I have no wish to be tortured again. Ask me a question and I will answer it.” Sounds like torture works, right? But as we know from the Senate and former CIA Director Leon Panetta, who wrote McCain in May 2011, that EITs did not play any more than an incidental role in the discovery of UBL.

No main characters in the film ever question the efficacy or corrupting effects of torture. Just the opposite. When Barack Obama appears — on television in a CIA conference room — he remarks that prohibiting torture is “part and parcel of an effort to regain America’s moral stature in the world.” In the foreground, another female CIA agent, Jessica (played by Jennifer Ehle) shakes her head in disgust.

Later, a CIA figure nicknamed “the Wolf” makes a speech on how his efforts to get bin Laden have been undermined by the sissies in Congress. “As you know,” he says, Abu Ghraib and Gitmo fucked us. The detainee program is now flat. We’ve got Senators jumping out of our asses…”

This line not wrong, in the sense that, in the context of a movie, it conveys the views of a particular character and, further, accurately represents those in the CIA — and there were many — who defended EITs. But what is pernicious about it is that the statement exists in a vacuum, as if, for the tough-minded folks who had “boots on the ground,” to use the expression Bigelow likes so much, there was no other possible point of view. But that’s wrong.

3) What is Missing

When it comes to torture, what is irresponsible about ZD30 is what it excludes.

The FBI and a great many CIA agents vigorously opposed the so-called “enhanced interrogation techniques” introduced by the CIA at the behest of the Bush Administration. These techniques were derived from the SERE program (SERE stands for “Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape) in which soldiers who are at risk of capture are administered “harsh techniques” they are likely to face at the hands of the enemy, including waterboarding. As part of this CIA “program,” three individuals were waterboarded: Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, Abu Zubaydah and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed.

Advocates of the CIA program like to cite Abu Zubaydah as an example of how waterboarding worked. But in fact, before Abu Zubaydah was waterboarded 83 times, he was interrogated by an FBI agent named Ali Soufan. After Soufan read Abu Zubaydah his Miranda rights, he used lawful interrogation techniques to get all the valuable information he had to offer, including the identity of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. More relevant to this film is the fact that KSM, during his waterboarding program, vigorously denied the importance of al-Kuwaiti. So confident was the CIA in the effectiveness of waterboarding — despite all evidence to the contrary — that the CIA actually assumed that KSM was telling the truth about the unimportance of al-Kuwaiti, when he was actually lying. The CIA’s unjustified confidence in waterboarding likely derailed the hunt for bin Laden until the interrogation of Ghul.

ZB30 also withholds how much damage was done by the false information obtained by waterboarding. Ibn al-Sheik al Libi was being interrogated successfully by the FBI when an impatient Bush Administration demanded that the CIA take over. The CIA wrapped him in duct tape and packed him in a wooden box to be shipped to Cairo where he was waterboarded. As a result he offered up information linking al Qaeda with Saddam Hussein which was used by Colin Powell when he gave his famous speech before the UN. Partially as a result, we invaded Iraq. Later on, the CIA admitted that al-Libi had given false information. But by then we already had “boots on the ground” in Iraq.

Kathryn Bigelow must have been delighted when she discovered a female CIA agent was at the heart of the hunt for bin Laden. But compare Maya’s infallibility in the film with the case of another female CIA agent — a redhead like Jessica Chastain — who was such a fan of waterboarding that she asked to “sit in” on the slow motion drowning of KSM. (As Jane Mayer notes in her book, “The Dark Side,” she was rebuffed by a superior who told her that waterboarding is not a spectator sport.) She supervised the kidnapping and torture of a man named Khaled el-Masri in the CIA’s “Salt Pit,” a black site in Afghanistan. Despite a valid German passport, the agent insisted on his continued torment and incarceration (despite the protests of Condelezza Rice) until it was finally revealed that the agent had mixed him up with another man named al-Masri. (Whoops, we tortured a man over a spelling mistake!) Without apology, he was then dropped on a lonely road in Albania to try to pick up the pieces of his life. Just this month, the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg declared his treatment at the hands of the CIA to have been torture — the first time this has happened. Where did we see this kind of cruel incompetence treated in ZD30?

If I am veering a bit far from the plot of the movie, I am doing so to make a point about a missed dramatic opportunity. Shaw once said that an argument between a right and a wrong is melodrama but that an argument between two rights is drama. When it came to the subject of torture in ZD30, there was no argument at all. And so a great dramatic opportunity was missed.

Manhola Dargis of the NY Times defends the accounts of torture in the film because they serve “as a claim — one made cinematically rather than with speeches — that these interrogation methods are unreliable when it comes to producing actionable information.” Then she says that to “omit [scenes of torture] from ZD30would have been a reprehensible act of moral cowardice.” Whoa! I haven’t heard anyone argue that the scenes themselves should have been omitted. But despite Dargis’ vivid imagination, there is no cinematic evidence in the film that EITs led to false information — lies that were swallowed whole because of the misplaced confidence in the efficacy of torture. Most students of this subject admit that torture can lead to the truth. But what Boal/Bigelow fail to show is how often the CIA deluded itself into believing that torture was a magic bullet, with disastrous results.

That raises a key question: With so much evidence of so many failures — practical, legal and moral — of the CIA’s “detainee program,” why did Boal and Bigelow fail to include it in the film?

My theory — and it is just a theory — is that Boal and Bigelow were seduced by their sources. It’s a common problem. When a writer or filmmaker gets extraordinary access, one is inclined to believe the person(s) granting the access. There is a significant constituency at the CIA which would like to defend its use of EITs in the War on Terror. This group is exemplified by Jose Rodriguez, the man who was responsible for destroying the videotapes of the CIA’s interrogations — which included waterboarding — of Abu Zubaydah and Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri. There are many, including me, who believe that Rodriguez should have been prosecuted for destroying evidence of possible crimes. (The DOJ declined to prosecute him.) Instead, he is now promoting his book in which he claims that waterboarding worked.

Many have been won over by the views of Rodriguez and those like him who suggest that what the CIA did was tough, but necessary and smart. It was none of those things. Yet by immersing us only in the world of the CIA, Boal and Bigelow don’t show us the perspective we need as viewers to see the lunacy of the CIA’s “detainee program.” If you want to reveal how tall a man is, you don’t shoot him in limbo; you must show him in relation to others. Likewise, how can viewers of ZD30 judge the CIA’s record if they can’t see how others were shocked by its cruelty, cowardice and stupidity of EITs. In the film, long after the torture of “Ammar,” an agent hands Maya a file folder with the real name of al-Kuwaiti. “If only I had this years ago,” says Maya. Because Maya is the glamorous heroine of the film, we identify with her and wonder about the inefficiency of her colleagues. But where is the character who wonders if Maya had spent less time slapping detainees around and more time scanning actual evidence — as the FBI did — she might have got to bin Laden’s courier much sooner.

I suspect that Boal and Bigelow’s sources at the CIA shared some of the views of Rodriguez. Of course, without knowing who those sources are, it’s impossible to say. What we do know, from correspondence that has been released, is that the CIA did grant extraordinary access to Boal and Bigelow.

While there is nothing wrong with access per se, what is concerning is the way that the CIA — and other military agencies — grant selective access. Sometimes that’s because of the star status of the project. The letters show how much the agency loved Hurt Locker (one of the rare times I agree with the perspective of the CIA). Other times, it’s because the agency is satisfied that the filmmakers have a vision that is “consistent” with that of the CIA. Whatever the reason, this will become a bigger and bigger concern for movies based on factual events (be they films with actors or documentaries). Why not give all American citizens to declassified information?

Whatever happened on ZD30, we can be sure of one thing. The CIA PR team must be delighted, particularly those who were supporters of the EIT “Program.” As former CIA director Michael Hayden noted, “I was happy the film was in the hands of such talent.”

Boal and Bigelow, by all accounts, are frustrated that the discussion of their film has been bogged down in a political debate that they want no part of. I would say, in response, that the debate is not political at all. The subject of torture is one of the great moral issues of our time. Boal and Bigelow shouldn’t run from it. They should engage it.

After all, the goal of Osama bin Laden was to provoke Americans to undermine our most fundamental values. Why is it not important — in a film about the hunt for bin Laden — to confront whether we, as Americans, allowed ourselves, in our lust for revenge, to lose our moral, legal and political bearings instead of trying, as Tony Lagouranis, an Army interrogator, told me, “to be as good as we can be.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Alex Gibney is the writer, director and producer of the 2008 Oscar-winning documentary Taxi to the Dark Side, the Oscar-nominated film Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, and Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson, narrated by Johnny Depp. Gibney is the recipient of many awards including the Emmy, the Peabody, the Du Pont Columbia Award, and the Grammy.