Merchandise marketed by Tony Poe, the real life Captain Kurtz who retired to live in San Francisco. He helped lead the CIA Hmong army of 30,000 in Laos. His dark humor here refers to the fact that he would pay highland villagers for severed human ears and, later, severed human heads.

Merchandise marketed by Tony Poe, the real life Captain Kurtz who retired to live in San Francisco. He helped lead the CIA Hmong army of 30,000 in Laos. His dark humor here refers to the fact that he would pay highland villagers for severed human ears and, later, severed human heads.

During the American War (as the people of Southeast Asia call it), the CIA was highly involved in encouraging Laotian opium production, much as it has now been involved in the cocaine trade in Colombia for decades. With USAID providing rice to Laos during the American War, productive land was freed up for opium production. CIA assets like General Vang Pao and Prince Sopsaisana were able to both make massive profits from heroin and win the loyalty of highland Hmong people by buying their opium at prices above normal market prices. In exchange for buying a village’s opium, which was transported out with U.S. aircraft, General Vang Pao would expect recruits from the village for the CIA’s anti-communist army. In this manner, the Hmong people fought for the CIA and for the Laotian monarchy against the Pathet Lao in a CIA run army directly under the command of Prince Sopsaisana. Prince Sopsaisana was also the head of the Asian Peoples Anti-Communist League.

CLICK ON IMAGES TO ENLARGE

In 1971, Prince Sopsaisana was busted in Paris with $13.5 million of heroin that was destined for New York City. Despite this being the biggest heroin bust in French history, the CIA successfully intervened to secure Prince Sopsaisana’s release and return to Laos.

The revolting duplicity of the US ruling class is seen in the CIA’s longstanding drug operations around the world, coupled with a heavy-handed and highly prudish, disruptive and costly “war on drugs” at home that never ends.

READ MORE ABOUT TONY POE’S REAL BIOGRAPHY. CLICK ON BAR BELOW

[learn_more] Anthony Alexander Poshepny (September 18, 1924 – June 27, 2003), known as Tony Poe, was a CIA paramilitary officer in what is now called Special Activities Division. He is best remembered for training the United States Secret Army in Laos during the Vietnam War. (As a brainwashed foot soldier at the service of America’s ruling elites, Poe personified the sordid ugliness of gung-ho anticommunism, and the CIA’s role in history as a mirror to the real face of American power.)

Early life and career

Accurate accounting of Poshepny’s career is complicated by government secrecy and by his tendency to embellish stories. For example, he often claimed to be a refugee from Hungary, but was actually born in Long Beach, California (He was of Czech descent). He joined the US Marine Corps in 1942 serving in the 2nd Marine Parachute Battalion and fought in the 5th Marine Division on Iwo Jima,[1] receiving two Purple Hearts. After graduating from San Jose State University in 1950, he joined the CIA and worked in Korea during the Korean War, training refugees for sabotage missions behind enemy lines.

After the Korean war, Poshepny joined the Bangkok-based CIA front company Overseas Southeast Asia Supply (SEA Supply), which provided military equipment to Kuomintang forces based in Burma. In 1958, Poshepny tried unsuccessfully to arrange a military uprising against Sukarno, the president of Indonesia. From 1958 to 1960, he trained various special missions teams, including Tibetan Khambas and Hui Muslims at Camp Hale, for operations in China against the Communist government. Poshepny sometimes claimed that he personally escorted the 14th Dalai Lama out of Tibet, but this has been denied, both by former CIA officers involved in the Tibet operation, and by the Tibetan government-in-exile. Laos[edit] The agency was impressed with Poshepny’s ability to train paramilitary forces quickly and awarded him the Intelligence Star in 1959. Two years later, working under Bill Lair, he was assigned with J. Vinton Lawrence to train Hmong hill tribes in Laos to fight North Vietnamese and Pathet Lao forces. In Laos, Poshepny gained the respect of the Hmong forces with practices that were barbaric by agency standards. He paid Hmong fighters to bring him the ears of dead enemy soldiers, and, on at least one occasion, he mailed a bag of ears to the US embassy in Vientiane to prove his body counts. He dropped severed heads onto enemy locations twice in a grisly form of psy-ops. Although his orders were only to train forces, he also went into battle with them and was wounded several times by shrapnel. Over several years, Poshepny grew disillusioned with the government’s management of the war. He accused then-Laotian Major General Vang Pao of using the war, and CIA assets, to enrich himself through the opium trade. The CIA extracted Poshepny from Laos in 1970 and reassigned him to a training camp in Thailand until his retirement in 1974. He received another Intelligence Star in 1975.

Read more

[/learn_more]

REGULAR ARTICLE RESUMES HERE

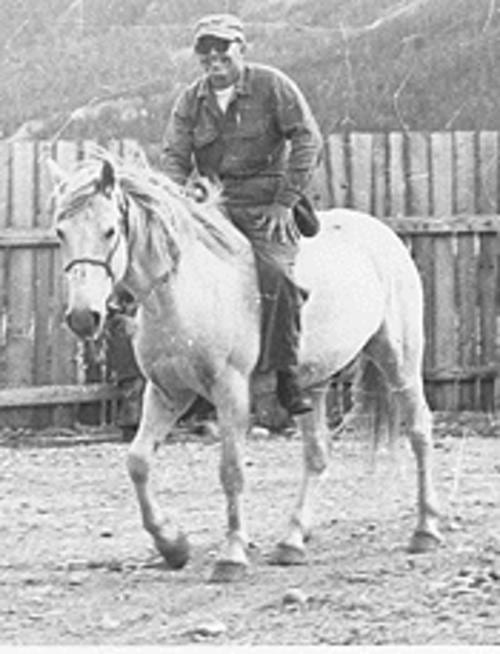

CIA leadership of the Hmong army was the inspiration for the creation of the Captain Kurtz character in the movie Apocalypse Now. The real life Captain Kurtz was known as Tony Poe (his real name was Anthony Posepheny). Before leading the Hmong he trained Tibetan counterrevolutionaries fighting for the Dalai Lama at a camp in Colorado, trained Kuomindang counterrevolutionaries for raids into China, and attempted to overthrow the Sukarno government in Indonesia in 1958 (the U.S. later succeeded at this in the 1960s and then proceeded to execute well over a million ill-advisably unarmed pacifistic Communists).

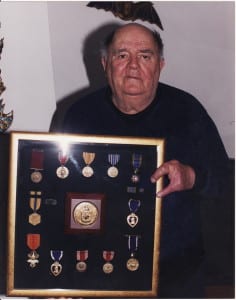

In Laos, Tony Poe would pay money for the murder of Pathet Lao Communists. Similar to the U.S. government buying the scalps of Native Americans in its genocide of those peoples, proof of the murder of Pathet Lao was supplied to Tony Poe through cutting off ears. At one point Tony Poe even stapled a human ear to a report he sent back to HQ as part of trying to answer their skepticism in regards to body counts. When Tony Poe found out that a father desperate for money cut off his own son’s ears to get the bounty, he then decided that he would only pay the bounty if the whole head was brought to him, thus assuring that the victim was dead. Far from the U.S. government sending Martin Sheen to kill Tony Poe, however, he now lives in San Francisco showing off his medals and complaining that he never gets invited to veteran’s meetings. Vang Pao is a wealthy businessman in Fresno California. Like Nazi war criminals, Tony Poe and Vang Pao should have been sent back to Laos and brought to justice.

Steven Argue of the Revolutionary Tendency

APPENDIX

The friends we keep—

The son of a big shot Laotian CIA asset, prominent in the Indochina wars, Prince Sopsaisana, has an interesting page devoted to memories about his father’s drug smuggling activities (besides being a puppet of the CIA and thereby betraying his people but not his class). Monirom Southakakoumar, who apparently makes a living as a designer, is refreshingly candid about the whole thing, perhaps as a matter of expiatory honesty or simply royal blood privilege. If true, his tale, has value as added evidence of the sheer perfidy of the CIA and why this organization so aptly represents the true face of American power. Below, an excerpt from Monirom’s story.

DAD SMUGGLED HEROIN for the CIA

Ethically, people are not born fully formed. They cannot be defined at the beginning of their lives the same way they can be at the end. Sometimes a moment can change things. Sometimes in an instant our choices are made for us. The betrayal of a trust. The revelation that our truths are ours alone. In the context of this truth my father cannot be judged or summed up by a single act. Yet in lives public and private, we see time and time again that a single moment can define what others think of us. Was my father rebuked at the end of the Vietnam War because he was not as accommodating to the CIA as General Vang Pao? General Vang Pao is considered a hero among the Hmong people. He was also identified as the mastermind behind the 2008 plot/coup to overthrow the current Laotian government. I tell you this because headlines like “Crown Prince Sopsaisana’s Opium Bust” are not very flattering.

When I was younger, and we lived in Laos, our house was gated. I always assumed it was for privacy, in retrospect I imagine it was also for our safety. The exterior walls were concrete, three feet thick and the circular driveway ended in steel gates 10 feet tall. Maybe not 10 feet tall, they could have been shorter, but when you’re nine years old everything is very imposing.

Back then I always noticed that people either loved my father or hated him vehemently. Maybe hated is too strong a word. I should say despised — in the way all politicians are despised. I could never understand why. He tried to explain it to me once. He explained how he had contracted with an organization much like Doctors Without Borders to provide additional support and healthcare for the Laotian people. Some of these doctors were Filipino. If you know how xenophobic most Asian cultures are, you know what is coming. The native Laotian doctors saw this as an afront, a commentary about how well they were caring for their own people. They became very offended. I’m making a generalization here, I’m sure many native Laotian doctors welcomed the help. Regardless, my father was used as a scapegoat, a whipping boy if you will. He was damned if he didn’t get the needed help and he was damned if he did. Sometimes you have to make the shitty call.

How long do you have to read this post? Seriously, I’m trying to save you some time. If you’re not a reader and you just want something to scan while you drink your coffee skip this post. Or wait until lunch. This is what I meant when I wrote “long-form narrative” in the ABOUT page of this blog. Buckle-up because this one requires commitment.

It is very hard to judge this situation once you realize that my father was not doing this for personal gain but on behalf of the CIA. Does the end justify the means? Also, just because you may not believe this blog entry doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. In retrospect, I’m pretty sure my Dad’s history was one of the possible reasons I didn’t get that design job in ’09 at Langley.

SOURCE I: Political Friendster provides this context:

The Laotian prince, Sopsaisana, was the head of the Asian Peoples Anti-Communist League, the chief political advisor of Vang Pao, military commander of the CIA’s Laotian Hmong army. The heroin itself was refined from Hmong opium at Long Tieng, the CIA’s headquarters in northern Laos, and given to Sopsaisana on consignment by Vang Pao. The consignment made its way from Vang Pao in Long Tieng to Sopsaisana in Vientiane via General Secord’s Air America. That, apparently, was an alternative Richard Nixon was willing to accept.

SOURCE II: Wikipedia has this short five sentence missive:

The Laotian prince Sopsaisana was the head of the Asian Peoples Anti-Communist League, the chief political advisor of Vang Pao, Vice President of the Laotian National Assembly and military commander of the CIA controlled Laotian Hmong army. In April 1971 Prince Sopsaisana, then Laos’s new Ambassador to France, arrived in Paris. After a tip-off, customs at Orly airport intercepted a valise containing 123 pounds of pure heroin, then the largest drug seizure in French history with an estimated value of $13.5 million. The Prince had planned to ship the drugs to New York. CIA stationed in Paris convinced the French to cover up the affair; Prince Sopaisana returned to Vientiane two weeks later.

SOURCE III: A more colorful retelling of the incident from the book, The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia by Alfred W. McCoy

Published August 1st 1972 by Harper & Row. (isbn: 0060129018) The excerpt:

The Golden Triangle: Heroin Is Our Most Important Product

“LADIES AND GENTLEMEN,” announced the genteel British diplomat, raising his glass to offer a toast, “I give you Prince Sopsaisana, the uplifter of Laotian youth.” The toast brought an appreciative smile from the lips of the guest of honor, cheers and applause from the luminaries of Vientiane’s diplomatic corps gathered at the send-off banquet for the Laotian ambassador-designate to France, Prince Sopsaisana. His appointment was the crowning achievement in a brilliant career. A member of the royal house of Meng Khouang, the Plain of Jars region, Prince Sopsaisana was vice-president of the National Assembly, chairman of the Lao Bar Association, president of the Lao Press Association, president of the Alliance Francaise, and a member in good standing of the Asian People’s Anti-Communist League. After receiving his credentials from the king in a private audience at the Luang Prabang Royal Palace on April 8, 1971, the prince was treated to an unprecedented round of cocktail parties, dinners, and banquets. (1) For Prince Sopsaisana, or Sopsai as his friends call him, was not just any ambassador; the Americans considered him an outstanding example of a new generation of honest, dynamic national leaders, and it was widely rumored in Vientiane that Sopsai was destined for high office some day.

The send-off party at Vientiane’s Wattay Airport on April 23 was one of the gayest affairs of the season. Everybody was there: the cream of the diplomatic corps, a bevy of Lao luminaries, and, of course, you-know who from the American Embassy. The champagne bubbled, the canapes were flawlessly French, and Mr. Ivan Bastouil, charge d’affaires at the French Embassy, Lao Presse reported, gave the nicest speech. (2) Only after the plane had soared off into the clouds did anybody notice that Sopsai had forgotten to pay for his share of the reception. When the prince’s flight arrived at Paris’s Orly Airport on the morning of April 25, there was another reception in the exclusive VIP lounge. The French ambassador to Laos, home for a brief visit, and the entire staff of the Laotian Embassy had turned out. (3) There were warm embraces, kissing on both cheeks, and more effusive speeches. Curiously, Prince Sopsaisana insisted on waiting for his luggage like any ordinary tourist, and when the mountain of suitcases finally appeared after an unexplained delay, he immediately noticed that one was missing. Angrily Sopsai insisted his suitcase be delivered at once, and the French authorities promised, most apologetically, that it would be sent round to the Embassy just as soon as it was found. But the Mercedes was waiting, and with flags fluttering, Sopsai was whisked off to the Embassy for a formal reception.

While the champagne bubbled at the Laotian Embassy, French customs officials were examining one of the biggest heroin seizures in French history: the ambassador’s “missing” suitcase contained sixty kilos of high-grade Laotian heroin worth $13.5 million on the streets of New York,(4) its probable destination. Tipped by an unidentified source in Vientiane, French officials had been waiting at the airport. Rather than create a major diplomatic scandal by confronting Sopsai with the heroin in the VIP lounge, French officials quietly impounded the suitcase until the government could decide how to deal with the matter.

Although it was finally decided to hush up the affair, the authorities were determined that Sopsaisana should not go entirely unpunished. A week after the ambassador’s arrival, a smiling French official presented himself at the Embassy with the guilty suitcase in hand. Although Sopsaisana had been bombarding the airport with outraged telephone calls for several days, he must have realized that accepting the suitcase was tantamount to an admission of guilt and flatly denied that it was his. Despite his protestations of innocence, the French government refused to accept his diplomatic credentials and Sopsai festered in Paris for almost two months until he was finally recalled to Vientiane late in June.

Back in Vientiane the impact of this affair was considerably less than earthshaking. The all-powerful American Embassy chose not to pursue the matter, and within a few weeks everything was conveniently forgotten (5) According to reports later received by the U.S. Bureau of Narcotics, Sopsai’s venture had been financed by Meo Gen. Vang Pao, commander of the CIA’s Secret Army, and the heroin itself had been refined in a laboratory at Long Tieng, which happens to be the CIA’s headquarters for clandestine operations in northern Laos.(6) Perhaps these embarrassing facts may explain the U.S. Embassy’s lack of action. In spite of its amusing aspects, the Sopsaisana affair provides sobering evidence of Southeast Asia’s growing importance in the international heroin trade. In addition to growing over a thousand tons of raw opium annually (about 70 percent of the world’s total illicit opium. (7) Southeast Asia’s Golden Triangle region has become a mass producer of high-grade no. 4 heroin for the American market. Its mushrooming heroin laboratories now rival Marseille and Hong Kong in the quantity and quality of their heroin production.

READ MORE HERE