By • The American Conservative

These weren’t Crusaders sacking Constantinople. These were our fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandfathers, doing it to the fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandfathers of our black neighbors.

Excerpt:

The problem, in this in as many other debates, is that there seems to be little ground between being “for” and “against” a phenomenon too historically complex to meaningfully “favor” and “oppose” — which is why the religious-conservative rush to answer Obama has produced a lot of arguments (including some of those quoted by Saletan) that effectively whitewash Christian history, romanticize the bloody muddle that was medieval warfare, minimize the harsh reality of pogroms and persecutions, and otherwise present fat targets for secular eye-rolling. … Wars fought on behalf of Christianity can only be justified as unfortunate necessities, and save in rare exceptions the faith’s warriors cannot — must not — be confused with its martyrs and its saints.

But I’m also not interested in an exercise in historical amnesia where the actual necessities of medieval geopolitics get wiped out of Western memory in favor of blanket condemnation of anyone who took the cross. If you want me to condemn pogroms in the Rhineland or the bloody aftermath of Jerusalem’s fall or the entirety of the Fourth Crusade, I will, and readily. But ask me if I’m sorry that Spain is Spain and not Al-Andalus, or if I regret Lepanto or Jan Sobieski’s gallop to Vienna, or if I wish that Saint Louis had somehow rescued Outremer or that aid had come to Constantinople in the 15th century — I’m not, I don’t, I do. There are parts of Christian civilization’s past that have to be simply judged, rejected, and disowned; that the list is depressingly long, too long for a presidential speech. But the Crusades are nowhere near that simple, and to disown them requires a kind of amputation, a schism with the past, a triumph of forgetfulness over the more complicated obligations of actually remembering.

There was news today that brought to mind something that has been on my mind ever since the savages of ISIS burned that Jordanian pilot. That deed rightly horrified and disgusted us, just as the beheadings have done. But here’s the thing: ISIS is doing nothing that wasn’t widely done in the United States to black people until well within living memory.

The New York Times wrote today on a new research report by an organization that has been studying lynching, and has documented almost 4,000 acts of extrajudicial murder by white mobs from the years 1877-1950. (1)

Most, but not all, of the deeds took place in the South. Five of the top 10 counties for lynching are in my home state, Louisiana. Here is a summary of the Equal Justice Initiative’s report. Here is an excerpt from the summary, in which the report’s authors describe the reasons why lynching occurred:

Lynchings Based on Fear of Interracial Sex. Nearly 25 percent of the lynchings of African Americans in the South were based on charges of sexual assault. The mere accusation of rape, even without an identification by the alleged victim, could arouse a lynch mob. The definition of black-on-white “rape” in the South required no allegation of force because white institutions, laws, and most white people rejected the idea that a white woman would willingly consent to sex with an African American man. In 1889, in Aberdeen, Mississippi, Keith Bowen allegedly tried to enter a room where three white women were sitting; though no further allegation was made against him, Mr. Bowen was lynched by the “entire (white) neighborhood” for his “offense.” General Lee, a black man, was lynched by a white mob in 1904 for merely knocking on the door of a white woman’s house in Reevesville, South Carolina; and in 1912, Thomas Miles was lynched for allegedly inviting a white woman to have a cold drink with him.

Lynchings Based on Minor Social Transgressions. Hundreds of African Americans accused of no serious crime were lynched for social grievances like speaking disrespectfully, refusing to step off the sidewalk, using profane language, using an improper title for a white person,suing a white man, arguing with a white man, bumping into a white woman, and insulting a white person. African Americans living in the South during this era were terrorized by the knowledge that they could be lynched if they intentionally or accidentally violated any social convention defined by any white person. In 1940, Jesse Thornton was lynched in Luverne, Alabama, for referring to a white police officer by his name without the title of “mister.” In 1919, a white mob in Blakely, Georgia, lynched William Little, a soldier returning from World War I, for refusing to take off his Army uniform. White men lynched Jeff Brown in 1916 in Cedarbluff, Mississippi, for accidentally bumping into a white girl as he ran to catch a train.

I picked these two out because I personally am aware of two such lynchings — one based on a fear of interracial sex, and the other based on a minor social transgression — that happened in my area in the first half of the 20th century, involving people (long dead) that I know. When you realize that people you know, men who were respected in their community during their lifetime, are actually murderers — well, this gets real, real fast.

And then there is this:

Public Spectacle Lynchings. Large crowds of white people, often numbering in the thousands and including elected officials and prominent citizens, gathered to witness pre-planned, heinous killings that featured prolonged torture, mutilation, dismemberment, and/or burning of the victim. White press justified and promoted these carnival-like events, with vendors selling food, printers producing postcards featuring photographs of the lynching and corpse, and the victim’s body parts collected as souvenirs. These killings were bold, public acts that implicated the entire community and sent a message that African Americans were sub-human, their subjugation was to be achieved through any means necessary, and whites who carried out lynchings would face no legal repercussions. In 1904, after Luther Holbert allegedly killed a local white landowner, he and a black woman believed to be his wife were captured by a mob and taken to Doddsville, Mississippi, to be lynched before hundreds of white spectators. Both victims were tied to a tree and forced to hold out their hands while members of the mob methodically chopped off their fingers and distributed them as souvenirs. Next, their ears were cut off. Mr. Holbert was then beaten so severely that his skull was fractured and one of his eyes was left hanging from its socket. Members of the mob used a large corkscrew to bore holes into the victims’ bodies and pull out large chunks of “quivering flesh,” after which both victims were thrown onto a raging fire and burned. The white men, women, and children present watched the horrific murders while enjoying deviled eggs, lemonade, and whiskey in a picnic-like atmosphere.

This was by no means a one-off thing. From the Times‘s story on the report:

The bloody history of Paris, Tex., about 100 miles northeast of Dallas, is well known if rarely brought up, said Thelma Dangerfield, the treasurer of the local N.A.A.C.P. chapter. Thousands of people came in 1893 to see Henry Smith, a black teenager accused of murder, carried around town on a float, then tortured and burned to death on a scaffold.

Until recently, some longtime residents still remembered when the two Arthur brothers were tied to a flagpole and set on fire at the city fairgrounds in 1920.

[dropcap]ISIS filmed[/dropcap] that poor Jordanian pilot burning to death as an act of revenge and terror. We call those Islamist fanatics animals. But white people did this often, and sometimes even made a public spectacle of it. “The white men, women, and children present watched the horrific murders while enjoying deviled eggs, lemonade, and whiskey in a picnic-like atmosphere.”

Mississippi Ku-Klux in the Disguises in Which They Were Captured, 1872. They were arrested in Tishomingo County, Mississippi for attempted murder. Wood engraving from photograph, Harper’s Weekly, 27 January 1872, (Public Domain)

In the EJI report is a photo of a 1919 clipping from a Jackson, Miss., newspaper reporting on a planned lynching in Ellisville, one that the Mississippi governor absurdly claimed he was powerless to stop. The paper reported that the Rev. L.G. Gates, a Baptist pastor from Laurel, Miss., was headed to Ellisville “to entreat the mob to use discretion.”

Oh, for the days when leading Christian pastors entreated lynch mobs not to stop in the name of God, but instead, to use discretion.

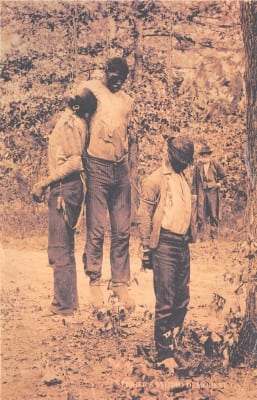

See the photo that illustrates this blog post? It shows the charred remains of Jesse Washington, a black man lynched by a mob in Waco, Texas, on May 15, 1916. He had confessed under police interrogation to murdering a white woman. From the Wikipedia account of his lynching:

Washington was tried for murder in Waco, in a courtroom filled with furious locals. He entered a guilty plea and was quickly sentenced to death. After his sentence was pronounced, he was dragged out of the court by observers and lynched in front of Waco’s city hall. Over 10,000 spectators, including city officials and police, gathered to watch the attack. There was a celebratory atmosphere at the event, and many children attended during their lunch hour. Members of the mob castrated Washington, cut off his fingers, and hung him over a bonfire. He was repeatedly lowered and raised over the fire for about two hours. After the fire was extinguished, his charred torso was dragged through the town and parts of his body were sold as souvenirs. A professional photographer took pictures as the event unfolded, providing rare imagery of a lynching in progress. The pictures were printed and sold as postcards in Waco.

That was not the Middle Ages. That was 99 years ago, in Texas. The killers were not berserker jihadis. They were the people of Waco, Texas, including the leadership of the city.

Just now, as I was googling for more information, I see that Bill Moyers wrote about the Waco lynching the other day — inspired, as I was, by ISIS burning the Jordanian pilot. Excerpt:

Sure enough, there it was: the charred corpse of a young black man, tied to a blistered tree in the heart of the Texas Bible Belt. Next to the burned body, young white men can be seen smiling and grinning, seemingly jubilant at their front-row seats in a carnival of death. One of them sent a picture postcard home: “This is the barbeque we had last night. My picture is to the left with a cross over it. Your son, Joe.”

The victim’s name was Jesse Washington. The year was 1916. America would soon go to war in Europe “to make the world safe for democracy.” My father was twelve, my mother eight. I was born 18 years later, at a time, I would come to learn, when local white folks still talked about Washington’s execution as if it were only yesterday. This was not medieval Europe. Not the Inquisition. Not a heretic burned at the stake by some ecclesiastical authority in the Old World. This was Texas, and the white people in that photograph were farmers, laborers, shopkeepers, some of them respectable congregants from local churches in and around the growing town of Waco.

More Moyers:

Yes, it was hard to get back to sleep the night we heard the news of the Jordanian pilot’s horrendous end. ISIS be damned! I thought. But with the next breath I could only think that our own barbarians did not have to wait at any gate. They were insiders. Home grown. Godly. Our neighbors, friends, and kin. People like us.

I see from the graphic in the EJI report that they appear to have documented at least 10 lynchings in West Feliciana Parish, where I live. I have written EJI for a copy of the report. I want to know who was killed, and under what circumstances. We all need to know these things, and face down what our ancestors did. These weren’t Crusaders sacking Constantinople. These were our fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandfathers, doing it to the fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandfathers of our black neighbors. Attention must be paid. That may be the only atonement available now, but it’s better than what we have had, which is nothing.

No, the American South (and other parts of America where racial terrorists ran rampant) was never run by fanatical theocrats who used grotesque public murders as a tool of terror. But if you were a black in the years 1877-1950, this was a distinction without much meaningful difference.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rod Dreher is a senior editor at The American Conservative. He has written and edited for the New York Post, The Dallas Morning News, National Review, the South Florida Sun-Sentinel, the Washington Times, and the Baton Rouge Advocate. Rod’s commentary has been published in The Wall Street Journal, Commentary, the Weekly Standard, Beliefnet, and Real Simple, among other publications, and he has appeared on NPR, ABC News, CNN, Fox News, MSNBC, and the BBC. He lives in St. Francisville, Louisiana, with his wife Julie and their three children. He has also written two books, The Little Way of Ruthie Leming and Crunchy Cons.

ADDENDUM

(1) A major motive for lynchings, particularly in the South, was the white society’s efforts to maintain white supremacy after emancipation of slaves following the American Civil War; they punished perceived violations of customs, later institutionalized as Jim Crow laws, which mandated racial segregation of whites and blacks, and second-class status for blacks. Economic competition was another major factor; independent black farmers or businessmen were sometimes lynched or suffered destruction of their property. In the Deep South, the number of lynchings was higher in areas with a concentration of blacks in an area (such as a county), dependent on cotton and at a time of low cotton prices, rising inflation, a predominance of Democrats, and competition among religious groups. and the economy went down.

Whites sometimes lynched blacks to gain financially and to establish political and economic control. For example, after the lynching of an African-American farmer or an immigrant merchant, the victim’s property would often become available to whites.[citation needed] In much of the Deep South, lynchings peaked in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as white racists turned to terrorism to dissuade blacks from voting in a period of disfranchisement. In the Mississippi Delta, lynchings of blacks increased beginning in the late 19th century as white planters tried to control former slaves who had become landowners or sharecroppers. Lynchings had a seasonal pattern in the Mississippi Delta; they were frequent at the end of the year, when sharecroppers and tenant farmers tried to settle their accounts. (Read more)