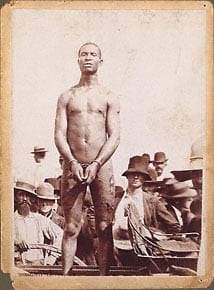

Photo showing the Laura Nelson lynching. The ugliness is still with us, albeit better concealed. Click on images to expand.

By Tom Mackaman

[dropcap]B[/dropcap]etween the years 1877 and 1950, 3,959 lynching of black men, women and children took place in 12 states of the American South, according to a study by the Equal Justice Initiative released last week.The data, based on five years of research in archives and on interviews with survivors and historians, reveals the extent of the racist terror that ruled in the American South for nearly three quarters of a century—between Reconstruction, the period after the American Civil War, and the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

A postcard with lynching victims sold in Kentucky in 1935.

The impact of lynching on blacks in the South, much like pogroms against Jews in czarist Russia, went far beyond those actually killed and their immediate families. “Lynchings were violent and public acts of torture that traumatized black people throughout the country and were largely tolerated by state and federal officials,” the report explains. The authors stress fear of lynching, for example, as a major factor in the Great Black Migration of millions of African Americans from the South to the urban centers of the North. They do not mention the lure of industrial jobs, but in fact the struggles for economic security and social dignity were two sides of the same coin.

The authors decry “an astonishing absence of any effort to acknowledge, discuss, or address lynching.” This is unsurprising in an area of the US still covered with monuments to racist politicians and the “heroes” that led the Confederacy of slaveholding states out of the union and into the Civil War (1861-1865). One aim of the Equal Justice Institute is to counter this prejudiced history by erecting memorials to the victims of lynching near the locations where they took place throughout the region.

The report distinguishes among six types of lynching: “1) those that resulted from a wildly distorted fear of interracial sex; 2) lynchings in response to casual social transgressions; 3) lynchings based on allegations of a serious violent crime; 4) public spectacle lynchings; 5) lynchings that escalated into large-scale violence targeting the entire African American community; and 6) lynchings of sharecroppers, ministers, and community leaders who resisted mistreatment.”

All of these had as their central aim the maintenance of the system of racial segregation known in the US as Jim Crow, which was fully implemented by the first years of the 20th century, and whose legal structures were not dismantled until the 1960s.

Most traumatic were the public spectacle lynchings. These were large spectator events that drew crowds sometimes numbering in the thousands, where souvenirs of body parts were often sold, alongside postcards and other mementos. The report describes several of these, among them the gruesome 1904 lynching in Doddville, Mississippi of Luther Holbert and his wife, who were accused of killing a wealthy white planter:

Both victims were tied to a tree and forced to hold out their hands while members of the mob methodically chopped off their fingers and distributed them as souvenirs. Next, their ears were cut off. Mr. Holbert was then beaten so severely that his skull was fractured and one of his eyes was left hanging from its socket. Members of the mob used a large corkscrew to bore holes into the victims’ bodies and pull large chunks of ‘quivering flesh,’ after which both victims were thrown onto a raging fire and burned. The white men, women, and children present watched the horrific event while enjoying deviled eggs, lemonade, and whiskey in a picnic-like atmosphere.

Any effort to draw attention to America’s history of racial violence merits praise, and this report offers new and valuable data. However, the authors interpret this important research in the framework of contemporary identity politics, an outlook that, in its principal American iteration, assigns social and political interests to groups of people based on race. The problem with this approach when it comes to history is that, as horrible and as clearly racist as the system of “Judge Lynch” was in the South, it is impossible to understand it outside of an analysis of the social order it upheld. It was not simply racism that gave rise to lynching, but a social system that underlay racist ideology.

Any effort to draw attention to America’s history of racial violence merits praise, and this report offers new and valuable data. However, the authors interpret this important research in the framework of contemporary identity politics, an outlook that, in its principal American iteration, assigns social and political interests to groups of people based on race. The problem with this approach when it comes to history is that, as horrible and as clearly racist as the system of “Judge Lynch” was in the South, it is impossible to understand it outside of an analysis of the social order it upheld. It was not simply racism that gave rise to lynching, but a social system that underlay racist ideology.

The word “sharecropping,” the impoverished crop lien system that replaced slavery as the dominant form of Southern labor after the Civil War, appears only once in the report. Slavery and sharecropping were both answers to what was once commonly called the “labor question.” This reality—that the racist Southern social order was built on extreme labor exploitation—once a basic conception even for American liberals, does not figure in the report.

“My thesis is essentially that slavery—the evil of slavery wasn’t involuntary servitude,” report director Bryan Stevenson stated in an interview. “It was this narrative of racial difference, this ideology of white supremacy. And so when [R]econstruction collapsed, to restore the racial hierarchy you had to use force and violence and intimidation. And in the South that manifested itself with these lynchings.”

In other words, slavery was not a system of forced labor and all that flowed from it— the selling apart of families and children, the driver’s lash, and so on—but “this narrative of racial difference.” Likewise, racial violence in the Jim Crow South was not about extreme labor exploitation and separating blacks from the white poor, much less maintaining the one-party dictatorship of the Democratic Party—which is referred to but once in the 27-page report summary—but about maintaining “White southern identity.”

To assert that racism caused racist violence, and to go no further, is a mere tautology. With such a perspective one cannot, for example, account for events like the murder of more than 35 blacks in Thibodaux, Louisiana in 1887. The Thibodaux Massacre came in response to a strike of some 10,000 sugar cane workers organized by the Knights of Labor. Perhaps 10 percent of the strikers were white. As the state geared up for the slaughter, Louisiana Governor Samuel Douglas McEnery, himself a sugar planter, declared, “God Almighty has himself drawn the color line.”

An Atlanta Georgian headline on April 29, 1913, showing that the police suspected Frank and Newt Lee.

The study also does not consider the lynching of whites or immigrants. There were, for example, a number of Italian immigrants lynched in the Jim Crow South, including 11 Sicilians killed in New Orleans in 1891; and in 1915 came the brutal public spectacle lynching of Jewish factory superintendent Leo Frank, in Georgia. But to the authors these murders are not worthy of study because they were done “to make the white community feel safe,” as Stevenson asserts.

BELOW Marietta (Cobb County), Aug. 17, 1915. Crowd gathers around after the lynching of Leo Frank.

Stevenson also dismisses the many lynchings that took place in the US West as examples of “frontier justice” that happened because “you didn’t have a functioning justice system … so people took things in their hands.” This is simply a cliché. In a 2006 study, Ken Gonzales-Day counted 352 lynchings in California alone between 1850 and 1935. Most of the victims were workers, the great majority Mexican, Chinese or American Indian.

BELOW Joseph Mackey Brown (1851–1932), one of the ringleaders in the Leo Frank lynching. He had served two terms as the Governor of Georgia, 1909–1911 and 1912–1913.

In their summary, the authors make no effort to analyze periods in which the numbers of lynchings spiked markedly. To do so raises interesting questions.

The greatest number of lynchings took place between 1890 and 1895, about 600 in all. This was precisely the period when the Farmers Alliance and the Colored Farmers Alliance organized hundreds of thousands of sharecroppers around a shared program that was hostile to the interests of the big planters, the new industrialists and the Democratic Party. It was only after the defeat of this southern arm of the Populist movement that the full force of segregation came to the fore in the wake of the notorious 1896 Supreme Court decision, Plessy vs. Ferguson.

The next largest number of lynchings occurred between 1915 and 1920, when over 500 blacks were murdered. This corresponded to the largest strike wave in US history (1916-1922), the Russian Revolution (1917), US mobilization for WWI (1917-1918), the Great Black Migration, anti-immigrant hysteria and the First Red Scare.

BELOW The lynching of Henry Smith, Paris, Texas, 1 February 1893. This act stands out for its sheer cold-blooded brutality and wanton contempt for the law. This is the real face of American savagery that the mainstream media, from Hollywood to television, have never shown. (3)

The report summary does not analyze the areas where lynching was most common. The data shows, however, that they were concentrated in the Deep South, and there in a relatively small number of counties. Out of all of the thousands of counties studied, a single one, Phillips County, Arkansas, in the Mississippi Delta, accounted for over 6 percent of all lynching, 243 in all.

Phillips County was the site of the 1919 Elaine Massacre in which an estimated 237 blacks were killed by a marauding mob of armed white men. At the time, black sharecroppers in the area were seeking to organize as the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America in order to demand better prices from white land owners for the cotton they produced. Phillips County was majority slave in 1860 and is today over 60 percent African American.

Number four on the lynching list, Tensas County, Louisiana, in 1910 had a population that was only 8 percent white.

Lynchings were least frequent in areas of the South removed geographically from the old plantation economy and most heavily white—North Carolina, eastern Tennessee, northern Georgia, etc. The whites of these largely mountainous areas—tellingly, these were also zones of militant resistance to the Southern Confederacy during the Civil War—are nonetheless lumped in by the report with the rest of the “White South” and equally implicated in its racial terror.

What happens if we consider lynching from the standpoint of social class? If sharecropping and wage labor in the South are considered as an extremely exploitative labor regime justified by a racist ideology and enforced by extreme violence, then the period of the authors’ study, 1877 until 1950, has interesting implications.

Their starting point, the year 1877, came in the same year as the “Great Uprising,” a sudden wave of general strikes and urban riots that swept the country from coast to coast in solidarity with striking trainmen. That struggle announced a period of extremely violent class warfare in the North, the West, and the South, that also counted its victims in the thousands. The last great labor massacre occurred on Memorial Day in 1937, when Chicago Police gunned down 10 striking steel workers.

What we then see in the period 1877 to 1950 is an extremely bloody class struggle, in the very country whose political parties, trade unions and academicians have always proclaimed more loudly than in any other that there are no social classes.

The report concludes with a political argument. It asserts that lynching did not really vanish, but now takes the form of the state executions so common in the US South. “Capital punishment remains rooted in racial terror, ‘a direct descendant of lynching,’” the report states, noting that while blacks make up 13 percent of the US population, since 1976 they have made up roughly 34 percent of all victims of the death penalty.

Race remains an undeniable factor in the American system of police repression. But just as was the case in the epochs of slavery and Jim Crow, it is ultimately an instrument of class exploitation. What has changed so markedly from those earlier periods is that today it is those who would don the mantle of “progressivism” who seek to promote the conception that race, and not class, is the decisive factor in American society.

The reactionary implications of this position are given away by the authors’ prescriptions. The problem with the death penalty, they write, is that “capital trials today remain proceedings with little racial diversity.” This is not a call for the abolition of the death penalty, but an appeal for more black leaders in its implementation. It simply ignores the legions of black mayors and police chiefs that have, since the 1960s, taken the reins of police repression in America’s cities, or for that matter, the fact that the chief law enforcement figure in the country, Barack Obama, is an African American.

Under the capitalist state, the police, prisons and death chambers are instruments of class oppression. The increasingly violent deployment of this repressive apparatus, and the threat that fascistic vigilante violence might reemerge, must be met with a unified response from the working class of all races and ethnicities.

[box]The author is a senior writer with wsws.org, organ of the Social Equality Party. [/box]