|

From our Virtual University archives.

Reposted by reader demand • Edited and expanded by Patrice Greanville

Originally posted on June 6, 2013 • Revised 29 June 2019

Texian leader Sam Houston’s victory over Gen. Santa Anna at the battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836 sealed the dismemberment of Mexico and the acquisition of an enormous territory almost as large as Western Europe. In the immediate aftermath of the war, some prominent Mexicans wrote that the war had resulted in “the state of degradation and ruin” in Mexico, further claiming, for “the true origin of the war, it is sufficient to say that the insatiable ambition of the United States, favored by our weakness, caused it.”

W W Ernesto “Che” Guevara, as a young medical student, in Argentina. “One Vietnam, Two Vietnams..Many Vietnams…”

By John Gerassi (published in 1969)

A great deal is being written in America these days about Pax Americana and American hegemony in the underdeveloped world. No longer able to blot out the obvious, even calm, rational, conscientious academicians are publicly lamenting America’s increasingly bellicose policies from Vietnam to the Dominican Republic. Suddenly, as if awakened from a technicolor dream, intellectuals are discovering such words as “imperialism” and “expansionism.” And they are asking: Why? Who’s to blame? What can be done to stop all this?

The questions are childish, the assumptions false, the implications naïve. They reflect a liberal point of view, one that claims that there is a qualitative difference between U.S. policies today and yesterday. In fact, American foreign policy has varied only in degree, not in kind. It has been cohesive, coherent, and consistent. What has varied has been its strength—and its critics.

The basic difference between American imperialism today and American imperialism a century ago is that it is more violent, more far-reaching, and more carefully planned today. But American foreign policy, at least since 1823, has always been assertive, always expansionist, always imperialist. Of course, it has rarely been pushed beyond America’s capabilities. Thus, when the United States was weak, its interventions abroad were mild. When its strength grew, so did its daring. Today, as the most powerful nation on earth, with a technological advance over other countries of mammoth proportions, the United States can be imperialistic on all continents with relative security.

The main reason why we have not had the opportunity to discuss this imperialism frankly and openly within the United States—in its journals, in academia, and on other platforms—is because Americans’ interpretation of history has been dominated by liberal historians whose basic view of life is characterized by their inability or unwillingness to connect events. Thus, when viewing Latin America, where American policy has always been crystal clear, Americans historians will admit, indeed will detail, U.S. interventions in specific countries of Central America or the Caribbean, will sometimes even posit an imperialist explanation for a whole period of American history, but will never draw overall conclusions, will never connect events, economics, and politics to arrive at a basic tradition or characteristic. To such historians, for example, there is little if any correlation between the events and policies of 1823 and those of 1845, or between 1898 and 1961.

By Patrice Greanville

[bg_collapse view=”button-orange” color=”#4a4949″ icon=”eye” expand_text=”CLICK ON THIS BUTTON TO EXAMINE THIS SPECIAL NOTE ON US EXPANSIONISM” collapse_text=”Close Sidebar” ]

The Mexicans certainly didn’t know it, all gringoes looking more or less the same to them, basically pale, tallish Northern Europeans, but the specific plague that hit Mexico in the 1840s was one of Scots-Irish origin. Most of the Texian heroes and agitators for Texas independence, and later absorption into the newly-minted United States were of Scots-Irish descent: Sam Houston, James Polk, William Walker, James Bowie, the legendary Andrew Jackson, and so on, themselves offshoots of the great Scots-Irish migration flowing out of the Ulster Plantation in the 1700s, and Scotland itself. Most of of the Scots-Irish had emigrated to the Ulster Plantation fleeing the almost constant wars —practically 800 years—on the Scottish-English border and later Charles I’s pressures to adopt the Episcopal faith over their fanatical Presbyterian allegiances. As the Wiki summary reminds us:

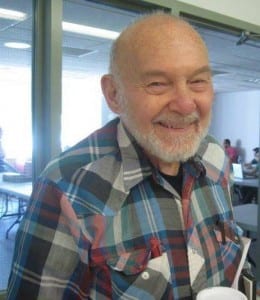

James K Polk, Mexico’s nemesis, in a 1849 daguerrotype. A protege of Jackson, his main legacy was one of immense territorial expansion at the expense of a much weaker nation, a land grab impossible to resist by White America’s pervasive racism and inherited anglo hatred for all things Spanish. Most of these emigres (to America) from Ireland had been recent settlers, or the descendants of settlers, from the Kingdom of England or the Kingdom of Scotland who had gone to Ireland to seek economic opportunities and freedom from the control of the episcopal Church of England and the Scottish Episcopal Church. These included 200,000 Scottish Presbyterians who settled in Ireland between 1608-1697. Many English-born settlers of this period were also Presbyterians, although the denomination is today most strongly identified with Scotland. When King Charles I attempted to force these Presbyterians into the Church of England in the 1630s, many chose to re-emigrate to North America where religious liberty was greater. Later attempts to force the Church of England’s control over dissident Protestants in Ireland were to lead to further waves of emigration to the trans-Atlantic colonies. (See Wikipedia, Scotch-Irish Americans).

James Knox Polk, the first of ten children, was born on November 2, 1795 in a log cabin[1] in what is now Pineville, North Carolina, in Mecklenburg County,[2] to a family of farmers.[3] His father Samuel Polk was a slaveholder, successful farmer, and surveyor of Scots-Irish descent. His mother Jane Polk named her firstborn after her father, James Knox.[2] The Polks had migrated to America in the late 1600s, settling initially on the Eastern Shore, then in south-central Pennsylvania and eventually moving to the Carolina hill country.[2]

Like many early Scots-Irish settlers in North Carolina, the Knox and Polk families were Presbyterian. (See Wikipedia, James K Polk)

It is quite possible that the family and cultural roots of James Polk instilled in him a fierce sense of raw nationalism, boundless entitlement to riches and empowerment through merit, both unfortunately underscored by racism, an almost inevitable virus infecting Europeans at the time (and surely present still today among far too many white Americans), especially when confronted with what he surely perceived as a degenerate and “inferior” semi-indigenous civilisation ludicrously in possession of a territory of almost incalculable value.

Gen. Santa Ana surrenders to a wounded Sam Houston after the battle of San Jacinto.

Ulster, Ireland, during the Ulster plantation period.

A person of integrity and moral courage Houston also stood out among his peers by his friendly and respectful attitude toward native Americans, with whom he had lived several years in his youth:

Cherokee tribe led by Ahuludegi (also spelled Oolooteka) on Hiwassee Island in the Hiwassee River, above its confluence with the Tennessee River. Ahuludegi had become hereditary chief after his brother moved west; American settlers in the area called him John Jolly. He became an adoptive father to Houston, giving him the Cherokee name of Colonneh, meaning “the Raven”.[12] Houston became fluent in the Cherokee language while living with the tribe. He visited his family in Maryville every few months. (See Wikipedia, Sam Houston)

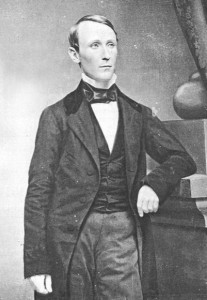

Sam Houston, photograph by Mathew Brady, c.1860–1863

Although Houston was a slave owner and opposed abolition, he opposed the secession of Texas from the Union. An elected convention voted to secede from the United States on February 1, 1861, and Texas joined the Confederate States of America on March 2, 1861. Houston refused to recognize its legality, but the Texas legislature upheld the legitimacy of secession. The political forces that brought about Texas’s secession were powerful enough to replace the state’s Unionist governor. Houston chose not to resist, stating, “I love Texas too well to bring civil strife and bloodshed upon her. To avert this calamity, I shall make no endeavor to maintain my authority as Chief Executive of this State, except by the peaceful exercise of my functions … ” He was evicted from his office on March 16, 1861, for refusing to take an oath of loyalty to the Confederacy, writing in an undelivered speech,

[39]

The Texas secession convention replaced Houston with Lieutenant Governor Edward Clark.[1] To avoid more bloodshed in Texas, Houston turned down U.S. Col. Frederick W. Lander‘s offer from President Lincoln of 50,000 troops to prevent Texas’s secession. He said, “Allow me to most respectfully decline any such assistance of the United States Government.”

After leaving the Governor’s mansion, Houston traveled to Galveston. Along the way, many people demanded an explanation for his refusal to support the Confederacy. On April 19, 1861 from a hotel window he told a crowd:

Let me tell you what is coming. After the sacrifice of countless millions of treasure and hundreds of thousands of lives, you may win Southern independence if God be not against you, but I doubt it. I tell you that, while I believe with you in the doctrine of states rights, the North is determined to preserve this Union. They are not a fiery, impulsive people as you are, for they live in colder climates. But when they begin to move in a given direction, they move with the steady momentum and perseverance of a mighty avalanche; and what I fear is, they will overwhelm the South.[40]

While many are led to believe that history is peopled with black and white characters, and this is sometimes the case, the more usual situation is one of gradations in gray, with good and evil mixed in often unsortable ways. Sam Houston’s life is a cautionary note in this regard.

—PG

[/bg_collapse]

Most liberal historians will admit today that the United States has often been imperialistic in Latin America up to 1933. Yet, slaves of their own rhetoric, they will inevitably cite the rhetoric of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the greatest liberal of them all, to insist that with the New Deal, American imperialism came to an end. They can make this statement because they are committed to the proposition that it is the American State Department which makes foreign policy—simply because it is supposed to—and also because of their own fear of being identified with Marxist ideology, a fear that leads them to refuse to interpret imperialism as economic.

Rare is the liberal historian who first asks himself just what imperialism is, or, if he does, rarer still is he who simply and succinctly admits that imperialism is a policy aimed at material gain. And this, in spite of the fact that he knows full well that there has never been a stronger or more consistent justification for intervening in the affairs of other countries than the expectation to derive material benefit therefrom. Imperialism has always operated in three specific, recognizable, and analyzable stages: (1) to control the sources of raw material for the benefit of the imperializing country; (2) to control the markets in the imperialized country for the benefit of the imperializing country’s producers; and (3) to control the imperialized country’s internal development and economic structure so as to guarantee continuing expansion of stages (1) and (2).

That has been our policy in Latin America. It began in recognizable manner in 1823 with President Monroe’s declaration warning nonhemisphere nations to stay out of the American continent. Because of its rhetoric, America’s liberal historians interpreted the Monroe Doctrine as a generous, even altruistic declaration on the part of the United States to protect its weaker neighbors to the south. To those neighbors, however, that doctrine asserted America’s ambitions: it said, in effect, Europeans stay out of Latin America because it belongs to the United States. A liberal, but not an American, Salvador de Madariaga, once explained its hold on Americans:

I only know two things about the Monroe Doctrine: one is that no American I have met knows what it is; the other is that no American I have met will consent to its being tampered with. That being so, I conclude that the Monroe Doctrine is not a doctrine but a dogma, for such are the two features by which you can tell a dogma. But when I look closer into it, I find that it is not one dogma, but two, to wit: the dogma of the infallibility of the American President and the dogma of the immaculate conception of American foreign policy.

Indeed, in the year 1824, Secretary of State (later President) John Quincy Adams made the Monroe Doctrine unequivocally clear when he told Simon Bolivar, one of Latin America’s great liberators, to stay out of—that is, not liberate—Cuba and Puerto Rico, which were still under the Spanish yoke. The Monroe Doctrine, said Adams, “must not be interpreted as authorization for the weak to be insolent with the strong.” Two years later, the United States refused to attend the first Pan American Conference called by Bolivar in Panama for the creation of a United States of Latin America. Further, the United States used its influence and its strength to torpedo that conference because a united Latin America would offer strong competition to American ambitions, on the continent as well as beyond. The conference failed and Bolivar concluded, in 1829: “The United States appear to be destined by Providence to plague America with misery in the name of liberty.”

Nor was the United States yet ready to put the Monroe Doctrine into effect against European powers, at least not if they were strong. In 1833, for example, England invaded the Falkland Islands, belonging to Argentina, and instead of invoking the Monroe Doctrine, the United States supported England. England still owns those islands today. Two years later, the United States allowed England to occupy the northern coast of Honduras, which is still British Honduras. England then invaded Guatemala, tripled its Honduran territory, and in 1839 took over the island of Roatan. Instead of reacting against England, the United States moved against Mexico. Within a few years Mexico lost half of its territory—the richest half—to the United States.

Imperialist adventurer William Walker, born in Nashville, Tenn. In 1854 the United States settled a minor argument with Nicaragua by sending a warship to bombard San Juan del Norte. Three years later, when one American citizen was wounded there President Buchanan levied a fine of $20,000 which Nicaragua could not pay, the United States repeated the bombardment, following it with Marines who proceeded to burn down anything that was still standing. The next year, the United States forced Nicaragua to sign the Cass-Irisarri Treaty, which gave the United States the right of free passage anywhere on Nicaraguan soil and the right to intervene in its affairs for whatever purpose the United States saw fit. If that does not make America’s material interest in Nicaragua obvious to a liberal, nothing will.

The liberal historian will insist, however, that during this period the State Department was often isolationist, indeed that it tried to enforce America’s neutrality laws strictly. That is true; but that does not mean, once again, that America was not imperialistic, for policy was not—and is not—made by the State Department but by those who profit from it. This was quite clear during the filibuster era, when American privateers raised armies and headed south to conquer areas for private American firms. In 1855, for example, William Walker, a Nashville-born doctor, lawyer, and journalist, who practiced none of these professions, invaded Nicaragua, captured Grenada, and had himself “elected” president of Nicaragua. He then sent a message to President Franklin Pierce asking that Nicaragua be admitted to the Union as a slave state, even though Nicaragua had long outlawed slavery. Walker was operating for private American corporations bent on exploiting Central America. The trouble was that these corporations were the rivals of Cornelius Vanderbilt’s Accessory Transit Company whose concessions Walker, as “President,” canceled. Vanderbilt thereupon threw his weight, money, and power behind other forces and they defeated Walker at Santa Rosa. He was then handed over to the United States Navy, brought back to the United States, and tried for violating neutrality laws. This had happened to him once before, after failing to conquer Lower California and he had then been acquitted. Now, he was again acquitted, and, in fact, cheered by the sympathetic jury.

Was the jury corrupt? Was it imperialist itself? Or was it simply reflecting the teachings, the propaganda, the atmosphere of the United States?

When the first colonizers to the United States had successfully established viable societies in their new land, they launched themselves westward. Liberal historians tell us that this great pioneering spurt was truly a magnificent impulse, a golden asset in America’s formation. In their expansionism to the west, the early Americans were ruthless, systematically wiping out the entire indigenous population. But they were successful, and, by and large, that expansion was completed without sacrificing too many of the basic civil rights of the white settlers. Thus, early America began to take pride in its system.

Later, as American entrepreneurs launched the industrialization of their country, they were equally successful. In the process, they exploited the new settlers, i.e., the working class and their children, but they built a strong economy. So once again they showed themselves and the world that America was a great country, so great in fact that it could not—should not—stop at its own borders. As these entrepreneurs expanded beyond America’s borders, mostly via the sea, and so developed America’s naval power, they were again successful. Thus once again they proved that their country was great.

It did not matter that Jeffersonian democracy, which liberal historians praise as the moral backbone of America’s current power, rested on the “haves” and excluded the “have nots” (to the point of not allowing the propertyless to vote). Nor did it matter that Jacksonian democracy, which liberal historians praise even more, functioned in a ruthless totalitarian setting in which one sector of the economy attempted, and, by and large, succeeded in crushing another. The rhetoric was pure, the results formidable, and therefore the system perfect. That system became known as “the American way of life,” a way of life in which the successful were the good, the unsuccessful the bad. America was founded very early on the basic premise that he who is poor deserves to be poor; he who is rich is entitled to the fruit of his power.

Since America was big enough and rich enough to allow its entrepreneurs to become tycoons while also allowing the poor to demand a fair shake–civil rights and a certain mobility–the rhetoric justifying all the murders and all the exploitations became theory. Out of the theory grew the conviction that America was the greatest country in the world precisely because it allowed self-determination. From there it was only a step to the conclusion that any country which could do the same would be equally great. The corollary, of course, was that those who did not would not be great. Finally, it became clear to all North Americans that he who is great is good. The American way of life became the personification of morality.

From America’s pride in its way of life followed its right to impose that way of life on non-Americans. Americans became superior, self-righteous, and pure. The result was that a new Jesuit company was formed. It too carried the sword and the cross. America’s sword was its Marines, its cross was “American democracy.” Under that cross, as under the cross brandished about by the conquistadors of colonial Spain, the United States rationalized its colonialism. Naval Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan even developed a theory based on Social Darwinism to prove that history is a struggle in which the strongest and fittest survive. The Protestant clergy also joined in to ennoble American imperialism.

The jury that tried Walker for violating America’s neutrality laws–which he had clearly violated–expressed that imperialist duty and colonialist spirit when it cheered Walker out of the court. It was simply reflecting its deep-rooted conviction that Nicaragua would be better off as a slave state in the Union than as a free country outside it. To that jury, as to the American people today, there can be only one democratic system worthy of the name–the American. There can be only one definition of freedom–American free enterprise. Thus, there is no need for the State Department to proclaim an imperialist policy; the Vanderbilts or the Rockefellers or the Guggenheims, the United Fruit Company or the Hanna Mining Company or the Anaconda Company can do what they please. After all, they represent democracy; they are the embodiment of freedom. What’s more, they know that when the chips are down, American might will stand behind them–or in front.

Within the last century America’s colonial expansionism, based on and strengthened by the American way of life, has become consistently bolder. In 1860 the United States intervened in Honduras. In 1871 it occupied Samana Bay in Santo Domingo. In 1881 it joined Peru in its war against Chile in exchange for the port of Chimbote (as a United States naval base), nearby coal mines, and a railroad from the mines to the port. In 1885 it again torpedoed the Central American Federation because it feared such an organization might jeopardize an Atlantic-Pacific canal owned by the United States.

Meanwhile, in 1884, official United States Government commercial missions were launched throughout Latin America for one purpose only, and as one such mission reported, that purpose was successfully carried out: “Our countrymen easily lead in nearly every major town. In every republic will be found businessmen with wide circles of influence. Moreover, resident merchants offer the best means to introduce and increase the use of the goods.” (Nothing, of course, has changed in this respect. Notice, for example, a report in Newsweek magazine of April 19, 1965: “American diplomats can be expected to intensify their help to United States businessmen overseas. Directives now awaiting Dean Rusk’s signature will remind United States embassies that their efficiency will be rated not only by diplomatic and political prowess but by how well they foster American commercial interests abroad. Moreover, prominent businessmen will be recruited as inspectors of the foreign service.”)

In 1895, President Cleveland intervened in Venezuela. In 1897, and again in 1898, the United States stopped further federation attempts in Central America. In 1898, after fabricating a phony war with Spain, the United States annexed Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam, and set up Cuba as a “republic” controlled by the United States through the Platt Amendment (1901). This amendment gave the United States the right to intervene in matters of “life, property, individual libery, and Cuban independence.’ That is, in everything.

The near-absence of significant public outcry in the United States against this policy of open imperialism in both the Caribbean and Pacific shows once again that the people of the United States were convinced that it was her destiny to expand, and that her superiority demanded it.

After 1900, even liberal historians lament America’s foreign policy. Theodore Roosevelt, who is nevertheless admired as one of America’s greatest presidents, intervened by force of arms in almost every Caribbean and Central American country. Naturally, the real beneficiaries were always American businessmen. It is worth repeating an often-quoted statement in this respect:

I helped make Mexico, and especially Tampico, safe for American oil interests. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenue in. I helped pacify Nicaragua for the international banking house of Brown Brothers. I brought light to the Dominican Republic for American sugar interests. I helped make Honduras “right” for American fruit companies..

That harsh but accurate indictment was supplied by a much-decorated United States patriot, Major General Smedley D. Butler of the United States Marine Corps.

Sandino Against such interventions, some local patriots fought back. In Haiti, where United States Marines landed in 1915 and stayed until 1934, 2,000 rebels (called cacos) had to be killed before the United States pacified the island. And there were other rebellions everywhere. In Nicaragua, one such rebel had to be tricked to be eliminated. Augusto Cesar Sandino (left) fought American Marines from 1926 until 1934 without being defeated, though the Marines razed various towns in Nicaragua, and, by accident, some in Honduras to boot. In 1934 he was offered “negotiations,” was foolish enough to believe them, came to the American embassy to confer with Ambassador Arthur Bliss Lane, and he was assassinated. (Such incidents are so common in American foreign policy that no intelligent rebel who has popular support can ever again trust negotiation offers by the United States, unless the setting and the terms of these negotiations can be controlled by him. It seems as if Ho Chi Minh is just that intelligent.)

On March 4, 1933, the United States officially changed its policy. Beginning with his inauguration address, Franklin D. Roosevelt told the world that American imperialism was at an end and that from now on the United States would be a good neighbor. He voted in favor of a nonintervention pledge at the 1933 Montevideo Inter-American Conference, promised Latin American countries tariff reductions and exchange trade agreements, and a year later abrogated the Platt Amendment. His top diplomat, Sumner Welles, even said in 1935, “It is my belief that American capital invested abroad, in fact as well as in theory, be subordinated to the authority of the people of the country where it is located.”

But, in fact, only the form of America’s interventionism changed. FDR was the most intelligent imperialist the United States has had in modern times. As a liberal, he knew the value of rhetoric; as a capitalist, he knew that whoever dominates the economy dominates the politics. As long as American interventionism for economic gain had to be defended by American Marines, rebellions and revolutions would be inevitable. When a country is occupied by American Marines, the enemy is always clearly identifiable. He wears the Marine uniform. But if there are no Marines, if the oppressors are the local militia, police, or military forces, if these forces’ loyalty to American commercial interests can be guaranteed by their economic ties to American commercial interests, it will be difficult, even impossible, for local patriots to finger the enemy. That FDR understood. Thus, he launched a brilliant series of policies meant to tie Latin American countries to the United States.

In 1938, FDR set up the Interdepartmental Committee of Cooperation with American Republics, which was, in effect, the precursor of today’s technical aid program of the Organization of American States (OAS). (The OAS itself had grown out of the Pan American Union which had been set up by Secretary of State James G. Blaine as “an ideal economic complement to the United States.”)

FDR’s Interdepartmental Committee assured Latin America’s dependency on the United States for technical progress. During the war, the United States Department of Agriculture sent Latin America soil conservation research teams who helped increase Latin America’s dependency on one-crop economies. In 1940, FDR said that the United States Government and United States private business should invest heavily in Latin America in order to “develop sources of raw materials needed in the United States.” On September 26, 1940, he raised the ceiling on loans made by the Export-Import Bank, which is an arm of the American Treasury, from $100 million to $700 million, and by Pearl Harbor Day most Latin American countries had received “development loans” from which they have yet to disengage themselves. Latin America’s economic dependency was further secured during the war through the United States lend-lease program, which poured $262,762,000 worth of United States equipment into eighteen Latin American nations (the two excluded were Panama, which was virtually an American property, and Argentina, which was rebellious.)

Roosevelt’s policies were so successful that his successors, liberals all whether Republican or Democrat, continued and strengthened them. By 1950 the United States controlled 70 percent of Latin America’s sources of raw materials and 50 percent of its gross national product. Theoretically at least, there was no more need for military intervention.

Latin American reformers did not realize to what extent the economic stranglehold by the United States insured pro-American-business governments. They kept thinking that if they could only present their case to their people they could alter the pattern of life and indeed the structure itself. Because the United States advocated, in rhetoric at least, free speech and free institutions, the reformers hoped that it would help them come to power. What they failed to realize was that in any underdeveloped country the vast majority of the population is either illiterate, and therefore cannot vote, or else lives in address-less slums and therefore still cannot vote. What’s more, there is no surplus of funds available from the poor. Thus, to create a party and be materially strong enough to wage a campaign with radio and newspaper announcements for the sake of the poor is impossible. The poor cannot finance such a campaign. That is why the United States often tried to convince its puppets to allow freedom of the press and freedom of elections; after all, the rich will always be the only ones capable of owning newspapers and financing elections.

Now and then, of course, through some fluke, a reformist president has been elected in Latin America. If he then tried to carry out his reforms, he was always overthrown. This is what happened in Guatemala where Juan Jose Arevalo and then Jacobo Arbenz were elected on reformist platforms. Before Arevalo’s inauguration in 1945, Guatemala was one of the most backward countries in Latin America. The rights of labor, whether in factories or in fields, including United Fruit Company plantations, had never been recognized; unions, civil liberties, freedom of speech and press had been outlawed. Foreign interests had been sacred and monopolistic, and their tax concessions beyond all considerations of fairness. Counting each foreign corporation as a person, 98 percent of Guatemala’s cultivated land was owned by exactly 142 people (out of a population of 3 million). Only 10 percent of the population attended school.

Arevalo and Arbenz tried to change these conditions. As long as they pressed for educational reforms, no one grumbled too much. Free speech and press were established, then unions were recognized and legalized, and finally, on June 17, 1952, Arbenz proclaimed Decree 900, a land reform which called for the expropriation and redistribution of uncultivated lands above a basic average. But Decree 900 specifically exempted all intensively cultivated lands, which amounted to only 5 percent of over 1,000-hectare farms then under cultivation. The decree ordered all absentee-owned property to be redistributed but offered compensation in twenty-year bonds at 3 percent interest, assessed according to declared tax value.

America’s agronomists applauded Decree 900. In Latin American Issues, published by the Twentieth Century Fund, one can read on page 179: “For all the furor it produced, Decree 900, which had its roots in the constitution of 1945, is a remarkably mild and fairly sound piece of legislation.” But, since much of Guatemalan plantation land, including 400,000 acres not under cultivation, belonged to the United Fruit Company, the United States became concerned, and when Arbenz gave out that fallow land to 180,000 peasants, the United States condemned his regime as Communist. The United States convened the OAS in Caracas to make that condemnation official and found a right-wing colonel named Carlos Castillo Armas, a graduate of the U.S. Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to do its dirty work. It fed him arms and dollars to set up a rebel force in Honduras and Nicaragua and helped him overthrow Arbenz. No matter how good a neighbor the United States wanted to appear, it was perfectly willing to dump such neighborliness and resort to old-fashioned military intervention when the commercial interests of its corporations were threatened.

Since then the United States has intervened again repeatedly, most visibly in the Dominican Republic in 1965 [plus, notably, since 1970 Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, where it toppled Pres. Allende and helped support the establishment of “dirty war” military dictatorships in the entire Southern Cone; and Brazil, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Grenada, El Salvador, Nicaragua (again during the Sandinistas governance) Panama, and Honduras—Eds]. Today, there can no longer be more than two positions in Latin America. As a result of the Dominican intervention, in which 23,000 American troops were used to put down a nationalist rebellion of 4,000 armed men, the United States has made it clear that it will never allow any Latin government to break America’s rigid economic control.

And what is that control? Today, 85 percent of the sources of raw material are controlled by the United States. One American company (United Fruit) controls over 50 percent of the foreign earnings (therefore of the whole economic structure) of six Latin American countries. In Venezuela, the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey (Rockefeller), through its subsidiary the Creole Oil Corporation, controls all the bases of the industrialization processess. Venezuela is potentially the second richest country in the world. Its $500 million-plus net annual revenue from oil could guarantee every family, counting it at 6.5 persons, an annual income of almost $3,000. Instead, 40 percent of its population lives outside the money economy; 22 percent are unemployed; and the country must use over $100 million a year of its revenue to import foodstuffs, although the country has enough land, under a proper agrarian reform, to be an exporter of food.

Chile, with enough minerals to raise a modern industrial state, flounders in inflation (21 percent in 1966) while, despite all the talk of “Revolution in Freedom,” there is only freedom for at most one-fifth of the population–and revolution for no one. So far, the best that Eduardo Frei has been able to do is to launch sewing classes in the slums. The right accuses him of demagogy, the left of paternalism; both are correct, while, as the Christian Science Monitor (September 19, 1966) says, “Many of the poor are apathetic, saying that they are just being used, as they have in the past.”

The continent as a whole must use from 30 to 40 percent of its foreign earnings to pay off interest and service charges, not the principal, on loans to the industrialized world, mostly the United States. The Alliance for Progress claims that it is helping Latin America industrialize on a social-progress basis. Now more than six years old, it has chalked up remarkable successes: right-wing coups in Argentina, Brazil, Honduras, Guatemala, Ecuador, the Dominican Republic, and El Salvador. In exchange, United States businessmen have remitted to United States $5 billion in profits while investing less than $2 billion. And the Alliance itself, which is supposed to lend money strictly for social-progress projects, has kept 86 percent of its outlay to credits for U.S.-made goods, credits which are guaranteed by Latin American governments and are repayable in dollars.

But then, under Johnson, the Alliance no longer maintains its social pretenses. In fact, no U.S. policy does, as President Johnson himself made clear last November when he told American GIs at Camp Stanley, Korea (and as recorded and broadcast by Pacifica radio stations): “Don’t forget, there are only 200 million of us in a world of three billion. They want what we’ve got and we’re not going to give it to them.”

Interventionist and imperialist policies of the United States in Latin America are now successfully in the third stage. Not only does the United States control Latin America’s sources of raw material, not only does it control its markets for American manufactured goods, but it also controls the internal money economy altogether. Karl Marx once warned that the first revolutionary wave in an imperialized country will come about as the result of frustration on the part of the national bourgeoisie, which will have reached a development stage where it will have accumulated enough capital to want to become competitive with the imperializing corporations. This was not allowed to happen in Latin America.

As American corporations became acutely plagued by surplus goods, they realized that they would have to expand their markets in underdeveloped countries. To do so, however, they would have to help develop a national bourgeoisie which could purchase these goods. This “national” bourgeoisie, like all such classes in colonialized countries, had to be created by the service industries, yet somehow limited so that it did not become economically independent. The solution was simple. The American corporations, having set up assembly plants in Sao Paulo or Buenos Aires, which they called Brazilian or Argentinian corporations, actually decided to help create the subsidiary industries themselves–with local money. Take General Motors, for example. First, it brought down its cars in parts (thus eliminating import duties). Then it assembled them in Sao Paulo and called them Brazil-made. Next it shopped around for local entrepreneurs to launch the subsidiary industries–seat covers, spark plugs, etc. Normally, the landed oligarchy and entrepreneurs in the area would do its own investing in those subsidiary industries, and having successfully amassed large amounts of capital, would join together to create their own car industry. It was this step that had to be avoided. Thus General Motors first offered these local entrepreneurs contracts by which it helped finance the servicing industries. Then it brought the entrepreneurs’ capital into huge holding corporations which, in turn, it rigidly controlled. The holding corporations became very successful, making the entrepreneurs happy, and everyone forgot about a local, competitive car industry, making GM happy.

This procedure is best employed by IBEC (International Basic Economy Corporation), Rockefeller’s mammoth investing corporation in Latin America. IBEC claims to be locally owned by Latin Americans, since it does not hold a controlling interest. But the 25 to 45 percent held by Standard Oil (it varies from Colombia to Venezuela to Peru) is not offset by the thousands of individual Latin investors who, to set policy, would all have to agree among themselves and then vote in a block. When one corporation owns 45 percent while thousands of individual investors split the other 55 percent, the corporation sets policy–in the U.S. as well as abroad. Besides, IBEC is so successful that the local entrepreneurs “think American” even before IBEC does. In any case, the result of these holding corporations is that the national bourgeoisie in Latin America has been eliminated. It is an American bourgeoisie. (See the analysis in this section by Carlos Romeo, a brilliant young Chilean economist who both worked with Che Guevara as a practical planner and taught with Regis Debray at the University of Havana, where together they worked out the theoretical consequences of Latin America’s reality.)

IBEC and other holding corporations use their combined local-U.S. capital to invest in all sorts of profitable ventures, from supermarkets to assembly plants. Naturally, these new corporations are set up where they can bring the largest return. IBEC is not going to build a supermarket in the Venezuelan province of Falcon where the population lives outside the money economy altogether and hence could not buy goods at the supermarket anyway. Nor would IBEC build a supermarket in Falcon, because there are no roads leading there. Thus, the creation of IBEC subsidiaries in no way helps develop the infrastructure of a country. What’s more, since such holding corporations have their tentacles in every region of the economy, they control the money market as well (which is why U.S. corporations backed, indeed pushed, the formation of a Latin American Common Market at the 1967 Punta del Este Conference. Such a common market would eliminate duties on American goods assembled in Latin America and exported form one Latin American country to another). Hence no new American investment needs to be brought down, even for the 45 percent of the holding corporations. A new American investment in Latin America today is a paper investment. The new corporation is set up with local funds, which only drains the local capital reserves. And the result is an industry benefiting only those sectors which purchase American surplus goods.

Having so tied up the local economic elites, the United States rarely needs to intervene with Marines to guarantee friendly governments. The local military, bought by the American-national interests, guarantees friendly regimes–with the approval of the local press, the local legal political parties, the local cultural centers, all of which the local money controls. And the local money is now tightly linked to American interests.

Latin American reformers have finally realized all this. They now know that the only way to break that structure is to break it–which means a violent revolution. Hence there are no reformers in Latin America any more. They have become either pro-Americans, whatever they call themselves, who will do America’s bidding, or else they are revolutionaries. (Perhaps the best example of this awakening is described in Fabricio Ojeda’s “Toward Revolutionary Power.” Ojeda, once a well-off student who hoped to bring about reforms through the electoral process–and got himself elected National Deputy–eventually became a revolutionary and guerrilla chief.)

American liberal historians, social scientists, and politicians insist that there is still a third way: a nonviolent revolution which will be basically pro-democracy, i.e., pro-American. They tell us that such a revolutionary process has already started and that it will inevitably lead to equality between the United States and its Latin neighbors. Liberal politicians also like to tell Americans that they should be on the side of that process, help it along, give it periodic boosts. In May, 1966, Robert Kennedy put it this way in a Senate speech: “A revolution is coming–a revolution which will be peaceful if we are wise enough; compassionate if we care enough; successful if we are fortunate enough–but a revolution which is coming whether we will it or not. We can affect its character, we cannot alter its inevitability.”

What Kennedy seemed incapable of understanding, however, was that if the revolution is peaceful and compassionate, if Americans can affect its character, then, it will be no revolution at all. There have been plenty of such misbred revolutions already. Let’s look at a couple.

In Uruguay, at the beginning of this century, a great man carried out the modern world’s first social revolution, and he was very peaceful, very compassionate, and very successful. Jose Batlle y Ordoñez gave his people the eight-hour day, a day of rest for every five of work, mandatory severance pay, a minimum wage, unemployment compensation, old-age pensions, paid vacations. He legalized divorce, abolished capital punishment, set up a state mortgage bank. He made education free through the university, levied taxes on capital, real estate, profits, horse racing and luxury sales (but not on income, which would, he thought, curtail incentive). He nationalized public utilities, insurance, alcohol, oil, cement, meat-packing, fish-processing, the principal banks. He outlawed arbitrary arrests, searches and seizures; separated the state from the church, which was forbidden to own property. He made it possible for peons to come to the city and get good jobs if they didn’t like working for the landed oligarchy. All of this he did before the Russian Revolution–without one murder, without one phony election.

But what happened? A thriving middle class became more and more used to government subsidy. When the price of meat and wool fell on the world market, the subsidies began to evaporate. The middle class was discontent. Used to government support, it demanded more. The government was forced to put more and more workers, mostly white-collar, on its payroll. The whole structure became a hand-me-down because the people had never participated in Batlle’s great revolution. Nobody had fought for it. It had come on a silver platter, and now that the platter was being chipped away, those who had most profited from the so-called revolution became unhappy.

Today, in Uruguay, more than one-third of the working force is employed by the government–but does not share in the decision-making apparatus. And the government, of course, is bankrupt. It needs help, and so it begs. And the United States, as usual, is very generous. It is rescuing Uruguay–but Uruguay is paying for it. It has too much of a nationalistic tradition to be as easily controlled as the [long-suffering Central American nations], but on matters crucial to the United States, Uruguay now toes the line. It either abstains or votes yes whenever the U.S. want the Organization of American States to justify or rationalize U.S. aggression. And, of course, free enterprise is once again primary.

The oligarchy still owns the land, still lives in Europe from its fat earnings. There are fewer poor in Uruguay than elsewhere in Latin America, but those who are poor stay poor. The middle class, self-centered and self-serving, takes pride in being vivo, shrewd and sharp at being able to swindle the government and one another. Uruguay is politically one of the most pleasant places to live, but only if one has money, only if one has abandoned all hope of achieving national pride–or a truly equitable society.

In 1910, while Uruguay’s peaceful revolution was still unfolding, Mexico unleashed its own–neither peacefully nor compassionately. For the next seven years blood was shed throughout the land, and the Indian peasants took a very active part in the upheaval. But Mexico’s revolution was not truly a people’s war, for it was basically controlled by the bourgeoisie. Francisco I. Madero, who led the first revolutionary wave, was certainly honest, but he was also a wealthy landowner who could never feel the burning thirst for change that Mexican peasants fought for. He did understand it somewhat and perhaps for that reason was assassinated with the complicity of the U.S. ambassador, Henry Lane Wilson. But he was incapable of absorbing into his program the unverbalized but nonetheless real plans that such peasant leaders as Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata embodied in their violent reaction to the long torment suffered by their people.

The bourgeoisie and the peasants, according to Gunder Frank,

…faced a common enemy, the feudal order and its supporting pillars of Church, army, and foreign capital. But their goals differed–freedom from domestic and foreign bonds and loosening of the economic structure for the bourgeoisie; land for the peasants. Although Zapata continued to press the interests of the peasants until his murder in 1919, the real leadership of the Revolution was never out of the hands of the bourgeoisie, except insofar as it was challenged by the Huerta reaction and American intervention. The elimination of feudal social relations was of course in the interests of the emerging bourgeoisie as well as of the peasants. Education became secularized, Church and state more widely separated. But accession to power by the peasantry was never really in the cards.

Thus, kept out of power, the peasants never genuinely benefited from their revolution. They did receive land periodically, but it was rarely fertile or irrigated, and the ejidos, communal lands, soon became the poorest sections of Mexico. The bourgeois-revolutionary elite grew into Mexico’s new oligarchy, and while some of its members did have darker skins than the old Spanish colonialists, the peasants were never integrated into the new Institutional Revolutionary Party power structure.

Today, not only do they rarely vote (in the 1958 presidential elections, for example, only 23 percent of the population voted officially, and that only after frauds upped the count), but they barely profit from the social laws instituted by the revolution. As Vincett Padgett, who is no revolutionary, has written: “To the marginal Mexican, the law and the courts are of little use. The formal institutions are not expected to provide justice. There is only acceptance and supplication. In the most unusual of circumstances there is for the marginal man the resort to violence, but the most significant point is that there exists no middle ground.”

In Mexico today, peasants still die of starvation. Illiteracy is about 50 percent, and 46 percent of school-age children do not attend schools at all. Most of the cotton is controlled by one U.S. outlet, Anderson-Clayton, and 55 percent of Mexican banks’ capital is dominated by the United States. Yet Mexico’s revolution was both anti-American and violent. What went wrong?

What went wrong is that the revolution failed to sustain its impulses. It is not enough to win militarily; a revolutionary must continue to fight long after he defeats his enemy. He must keep his people armed, as a constant check against himself and as a form of forcing the people’s participation in his revolutionary government. Yet he must also be careful not to guide this popular participation into a traditional form of party or state democracy, lest the intramural conflicts devour the revolution itself, as they did in Bolivia. He must make the transition from a generalized concept of anti-Americanism to a series of particular manifestations–that is, he must nationalize all the properties belonging to Americans (or Britons or Turks or whoever is the dominating imperialist power). Like all of us who can never find ourselves, psychologically, until we face death, until we sink to such an abyss that we can touch death, smell it, eat it, and then, and only then, rise slowly to express our true selves, so too for the revolution and the revolutionary. Both must completely destroy in order to rebuild, both must sink to chaos in order to find the bases for building the true expression of the people’s will. Only then can there be a total integration of the population into the new nation.

I am not trying here to define a psychological rationalization for violent revolution. What I am maintaining is that if one wants an overhaul of society, if one wants to establish an equitable society, if one wants to install economic democracy, without which all the political democracy in heaven and Washington is meaningless, then one must be ready to go all the way. There are no shortcuts to either truth or justice.

Besides, violence already exists in the Latin America continent today, but it is a negative violence, a counterrevolutionary violence. Such violence takes the form of dying of old age at twenty-eight in Brazil’s Northeast. Or it is the Bolivian woman who feeds only three of her four children because the fourth, as she told me, “is sickly and will probably have died anyway and I have not enough food for all four.”

Liberals, of course, will argue that one can always approximate, compromise, defend the rule of law while working for better living conditions piece by piece. But the facts shatter such illusions. Latin America is poorer today than thirty years ago. Fewer people drink potable water now than then. One-third of the population live in slums. Half never see a doctor. Besides, every compromise measure has either failed or been corrupted. Vargas gave Brazilian workingmen a class consciousness and launched a petroleum industry; his heirs filled their own pockets but tried to push Brazil along the road to progress. They were smashed by the country’s economic master, the United States. Peron, whatever his personal motivation, gave Argentinians new hopes and new slogans; his successors, pretending to despise him, bowed to U.S. pressure, kept their country under their boot and sold out its riches to American companies. In Guatemala, as we saw, Arevalo and then Arbenz tried to bring about social and agrarian reforms without arming the people, without violence. The U.S. destroyed them by force, and when the right-wing semidictatorship of Ydigoras Fuentes decided to allow free elections in which Arevalo might make a comeback, America’s great liberal rhetorician, President Kennedy, ordered Ydigoras’ removal, as the Miami Herald reported. In the Dominican Republic, a people’s spontaneous revulsion for new forms of dictatorships after thirty-two years of Trujillo was met by U.S. Marines. And so on; the list is endless.

Latin America’s revolutionaries know from the experience of the Dominican Republic, of Guatemala, and of Vietnam that to break the structure is to invite American retaliation. They also realize that American retaliation will be so formidable that is may well succeed, at least under normal conditions. In Peru, in 1965, Apra Rebelde went into the mountains to launch guerrilla warfare against the American puppet regime of Belaunde. Gaining wide popular support from the disenfranchised masses, it believed that it could go from phase number one (hit-and-run tactics) to phase number two (open confrontation with the local military). It made a grievous mistake, because the United States had also learned from its experience in Vietnam. It knew that it could not allow the local military to collapse or else it would have to send half a million men, as it had in as small a country as Vietnam. The U.S. cannot afford half a million men for all the countries that rebel. Thus, as soon as Apra Rebelde gathered on the mountain peak of the Andes for that phase number two confrontation, the U.S. hit it with napalm. Apra Rebelde was effectively, if only temporarily, destroyed; its leaders, including Luis de la Puente Uceda and Guillermo Lobaton, were killed.

But the guerrillas have also learned from that mistake. Today, in Guatemala, Venezuela, Colombia, and Bolivia, strong guerrilla forces are keeping mobile and are creating such havoc that the U.S. is forced to make the same mistake it did in Vietnam: it is sending Rangers and Special Forces into combat. In Guatemala, as of January 1, 1967, twenty-eight Rangers have been killed. The United States through its partners in Venezuela and Bolivia has again used napalm, but this time with no success. In Colombia, the U.S. is using Vietnam-type weapons as well as helicopters to combat the guerrillas, but again without notable success. New guerrilla uprisings are taking place (as of May, 1967), in Brazil, Peru, and Ecuador.

But, even more important, a new attitude has developed–an attitude that had been clearly enunciated by Che Guevara who died in Bolivia seeking to organize rebellion. That attitude recognizes that the United States cannot be militarily defeated in one isolated country at a time. The U.S. cannot, on the other hand, sustain two, three, five Vietnams simultaneously. If it tried to do so, its internal economy would crumble. Also, its necessarily increasing repressive measures at home, needed to quell rising internal dissent, would have to become so strong that the whole structure of the United States would be endangered from within.

The attitude further exclaims with unhesitating logic that imperialism never stops by itself. Like the man who has $100 and wants $200, the corporation that gets $1 million lusts for $2 million and the country that owns one continent seeks to control two. The only way to defeat it is to hit each of its imperialist tentacles simultaneously. Thus was Caesar defeated. Thus also was Alexander crushed. Thus too was the imperialism of France, of England, of Spain, of Germany eventually stopped. And thus will the United States be stopped.

Che Guevara had no illusions about what this will mean in Latin America. He wrote: “The present moment may or may not be the proper one for starting the struggle, but we cannot harbor any illusions, we have no right to do so, that freedom can be obtained without fighting. And these battles shall not be mere street fights with stones against tear-gas bombs, nor pacific general strikes; neither will they be those of a furious people destroying in two or three days the repressive superstructure of the ruling oligarchies. The struggle will be long, harsh, and its battlefronts will be the guerrilla’s refuge, the cities, the homes of the fighters–where the repressive forces will go seeking easy victims among their families–among the massacred rural populations, in the villages or in cities destroyed by the bombardments of the enemy.”

Nor shall it be a gentleman’s war, writes Che. “We must carry the war as far as the enemy carries it: to his home, to his centers of entertainment, in a total war. It is necessary to prevent him from having a moment of peace, a quiet moment outside his barracks or even inside; we must attack him wherever he may be, make him feel like a cornered beast wherever he may move. Then his morale will begin to fall. He will become still more savage, but we shall see the signs of decadence begin to appear.”

Che concludes candidly: “Our soldiers must hate; a people without hatred cannot vanquish a brutal enemy.”

This analysis is the inevitable and necessary conclusion of anyone who faces squarely the history of American imperialism and its effect on the imperialized people. Latin America today is poorer and more suffering than it was ten years ago, ten years before that, and so on back through the ages. American capital has not only taken away the Latin American people’s hope for a better material future but their sense of dignity as well.

This analysis will shock the liberals and they will reject it. But then they are responsible for it, for American foreign policy has long been the studied creation of American liberals. That is why an honest man today must consider the liberal as the true enemy of mankind. That is why he must become a revolutionary. That is why he must agree with Che Guevara that the only hope the peoples of the world have is to crush American imperialism by defeating it on the battlefield, and the only way to do that is to coordinate their attacks and launch them wherever men are exploited, wherever men are suffering as the result of American interests. The only answer, unless structural reforms can be achieved in the United States which will put an end to the greed of American corporations, is as Che Guevara has said, the poor and the honest of the world must arise to launch simultaneous Vietnams.

In Revolution in the Revolution?, Regis Debray tried to give the first of many theoretical systemizations as to how this coordinated, armed struggle can be waged. American readers, who generally had never heard of Debray until that pamphlet became a best seller, are quick to condemn him for his lack of analytical preliminaries. But Debray is no superficial pamphleteer; though he makes some important errors in Revolution in the Revolution?, he is a serious student of the Latin American scene and had published some extremely lucid essays on the political and methodological aspects of revolution (one of which is included in this section) prior to Revolution in the Revolution?, which was meant as a working paper anyway.

In this paper, the most important change in tactics that he suggests is the constant creation of guerrilla fronts in underdeveloped countries. These fronts, he says, must be headed by the revolutionary vanguards, commanded by the revolutionary elite itself. it is crucial, he claims, that the political and military leadership be combined into one command, indeed into one man. Leaving the military considerations aside, what this means politically is that the standard practices of the Communist parties must be abandoned. No longer can bureaucrats sit in the cities coordinating strikes, electoral campaigns, and quasi-subversive fronts. From now on, revolutionaries must wage direct war against imperialism. Not to do so, says Debray, is to betray the revolution, to betray the people.

At the beginning of August, 1967, Latin America revolutionaries and Communists met in Havana to discuss these new concepts of direct confrontation with imperialism. The meeting was called the Organization of Latin American Solidarity (OLAS), and out of it came a new International, a Marxist-Leninist-Revolutionary International, which carefully spelled out the necessity of armed struggle as the only way of defeating imperialism and establishing a socialist world. The traditional Communist parties of the Americas, and of course the observers and representatives from the socialist countries of Europe, which all uphold Russia’s policy of coexistence, objected to the Cuban position. But backed by representatives from the guerrilla fronts of Latin America, the Cuban line prevailed. As long as imperialism exists, as long as the United States dominates a single country beyond its borders, as long as U.S. companies exploit the poor and the underdeveloped, no Communist has the right to call himself a Communist unless he fights, unless his solidarity with combatants is expressed in deeds and not words. Thus, Russia itself was condemned for giving material aid to oligarchical countries, and the Moscow-lining Communist parties were chastised for their opportunistic tactics of legal struggle through the electoral process established by the imperialists and repressive governments. OLAS demanded clear-cut definitions, and it defined its own position.

But the traditional Communist parties were not very happy. Though they did not walk out of the conference, they made it clear that they would not accept the OLAS hard line. This, said Fidel on August 10, at the closing session of OLAS, was nothing less than treason. Those who support peaceful coexistence with imperialism, when imperialism is slaughtering and exploiting so many people all over the world, are not revolutionaries, no matter what they call themselves. They belong to a new, vast “mafia,” whose ultimate goal is to serve the desires of a new form of the bourgeoisie. Fight, Fidel said, or pass forevermore into the enemy camp.

[1969]

ABOUT THE AUTHOR  John Gerassi was a professor and journalist born in Paris on July 12, 1931, and died in New York City July 26, 2012. Gerassi wrote a number of books on Latin America, Jean-Paul Sartre, and political affairs. He taught at a variety of colleges and universities in the United States and in France. Most notably, Gerassi was a longtime professor in the Political Science department at Queens College of the City University of New York. He taught at Queens College from 1981 until his passing. He was an activist in the New Left and a leading thinker regarding the significance of Sartre's work. His father was Fernando Gerassi, an anarchist general who defended the Republic from Franco during the Spanish Civil War. John Gerassi was a professor and journalist born in Paris on July 12, 1931, and died in New York City July 26, 2012. Gerassi wrote a number of books on Latin America, Jean-Paul Sartre, and political affairs. He taught at a variety of colleges and universities in the United States and in France. Most notably, Gerassi was a longtime professor in the Political Science department at Queens College of the City University of New York. He taught at Queens College from 1981 until his passing. He was an activist in the New Left and a leading thinker regarding the significance of Sartre's work. His father was Fernando Gerassi, an anarchist general who defended the Republic from Franco during the Spanish Civil War.

Our special thanks to B. Havlena for transcribing this important article.

Patrice Greanville is The Greanville Post's founding (and chief) editor.

This essay appeared in Latin American Radicalism, A Documentary Report on Left & Nationalist Movements (Random House, 1969), edited by I.L. Horowitz, J. de Castro and J. Gerassi.

|