Ask any visitor to Australia what they’d like to do and they’ll probably tell you they’d love to cuddle a koala. If they go to a wildlife reserve they might get their wish but out in the wild, finding a koala is getting harder and harder to do.

“I often think to myself that, you know, if we can’t save the koalas, what can we save?” Dr Michael Pyne, senior vet Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary

In key parts of Australia, koalas are dying in big numbers. In Queensland, New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory the attrition rate has been so high the Federal Government responded by placing koalas on the Threatened Species “at risk” list.

“The only reason we’ve had to intervene at all is the states on their own have allowed numbers to continue to go into freefall.” Federal Environment Minister Tony Burke

Why is this happening? The answer is simple. Development, cars, dogs, disease and climate change are making life tough for these fascinating creatures. The bigger question is, what can be done to save them?

Four Corners travels to three koala hot spots to try to understand the problems they confront. First, reporter Marian Wilkinson looks at South Eastern Queensland, an area where development is exploding. Large tracts of bushland have been set aside for housing and other urban developments, which means koalas will lose their homes and food. She meets a group of scientists forced to play catch up, trying to devise a plan that will save the endangered animals.

It is estimated that due to climate change and land clearing, koalas will be extinct in NSW by 2050. #MagicalLandOfOz

In New South Wales koalas are also finding the going tough. West of the Great Dividing Range, conservation programs have tried to create places where the animals can live and be protected from predators, but rising temperatures are putting them at risk. In ultra-hot weather koalas simply dehydrate and die.

In Victoria the situation is very different, but equally as troubling. In that State the koala population was revived with descendents from a small colony on French Island, south-east of Melbourne. Unfortunately, because this revived population came from a small group, there is a limited gene pool, which means major environmental changes leaves many of them at risk too.

There is no doubt Australians want to save this much-loved national icon, but are we prepared to compromise development to protect the koalas’ natural habitat?

“Koala Crunch Time”, reported by Marian Wilkinson and presented by Kerry O’Brien, goes to air on Monday 20th August at 8.30pm on ABC1. It is replayed on Tuesday 21st August at 11.35pm. It can also be seen on ABC News 24 on Saturday at 8.00pm, ABC iview or at abc.net.au/4corners.

Transcript

KOALA CRUNCH TIME – 20 AUGUST 2012

KERRY O’BRIEN, PRESENTER: Could it really be true that we’re bearing witness to the unstoppable decline of a beloved national icon.

Welcome to Four Corners.

Statistics can be deceiving, but what you’re about to see leaves little room for doubt that koalas are in serious trouble in much of their natural habitat.

They’ve fallen victim to a lethal mix of urban development, massive land clearing and disease. That’s before you even start to consider the impact of climate change.

Scientists estimate that in New South Wales over the past two decades koala numbers have dropped by a third. And in at least one significant part of Queensland by as much as 80 per cent.

The crash is so severe that the Federal Government recently took the controversial step of placing koalas in New South Wales, Queensland and the ACT on the threatened species list. Even in Victoria, where the koalas appear to be flourishing against the trend, experts have warned that their future too is far from secure.

It’s a very real question now: with time running out, can we save the koala?

Marian Wilkinson reports.

(Footage of koala bodies in the morgue)

MARIAN WILKINSON, REPORTER: Mauled by dogs, hit by cars, or riddled with disease. Koalas beyond the help of any caring vet.

In wildlife hospitals and shelters up and down the east coast, koalas are now being euthanized in large numbers.

Australia’s listing of the koala as a threatened species is an admission of defeat described by some as a national shame.

DR MICHAEL PYNE, SENIOR VET, CURRUMBIN WILDLFE SANCTUARY HOSPITAL: We’ll see well over 200 koalas admitted into our hospital this year. And yet it was only five years ago we were only admitting 25 koalas. There’s been this incredible surge of koalas coming through, and it’s really quite frightening.

TONY BURKE, FEDERAL ENVIRONMENT MINISTER: The only reason that we’ve had to intervene at all is the states on their own have allowed the numbers to continue to go into freefall.

DR STEVE PHILLIPS, CONSULTING KOALA ECOLOGIST: I know what to do and so do many other people. But it’s whether we’re actually allowed to put what we know into practice to make it happen or whether the cultural juggernaut that our society is just keeps rolling over until eventually someone wakes up one day and goes, ‘gee, there’s no koalas left on the east coast. Weren’t we silly?’

(Footage of Gold Coast apartments and beaches)

MARIAN WILKINSON: There are few places where the development juggernaut rolls out as brutally as it does on Queensland’s Gold Coast.

Behind the 70 kilometres of golden beaches and glitzy high rise, big tracts of eucalypt trees that once fed local koalas are right now being flattened to make way for the next Gold Coast satellite city.

(Footage of Coomera development site)

Here at Coomera, developers promise affordable housing and open space for growing families.

DR STEVE PHILLIPS: The reality was is that you know probably 30 to 40 per cent of the area that we had assessed already had development approvals in place. And so it was going to happen and it was going to happen fairly quickly.

MARIAN WILKINSON: For Queensland’s koala, this is ground zero.

(Footage of dogs barking in urban backyards in East Coomera)

It’s one of Australia’s most loved native animals, but it could be extinct within fifty years. Habitat loss, disease and predators are taking their toll on our koalas and now climate change is also a deadly threat. But scientists, animal carers and conservationists are working together to try and halt the decline as Philippa McDonald reports.

DR STEVE PHILLIPS: East Coomera is where you understand why the koala is a threatened species. Here, right now, their homes are being destroyed so we can build ours.

DR STEVE PHILLIPS: This would have been intact forest, quite mature forest when we did our work in 2007 and it’s now ah been reduced to, you know, probably 500, 600 metre, square metre blocks, with houses on them.

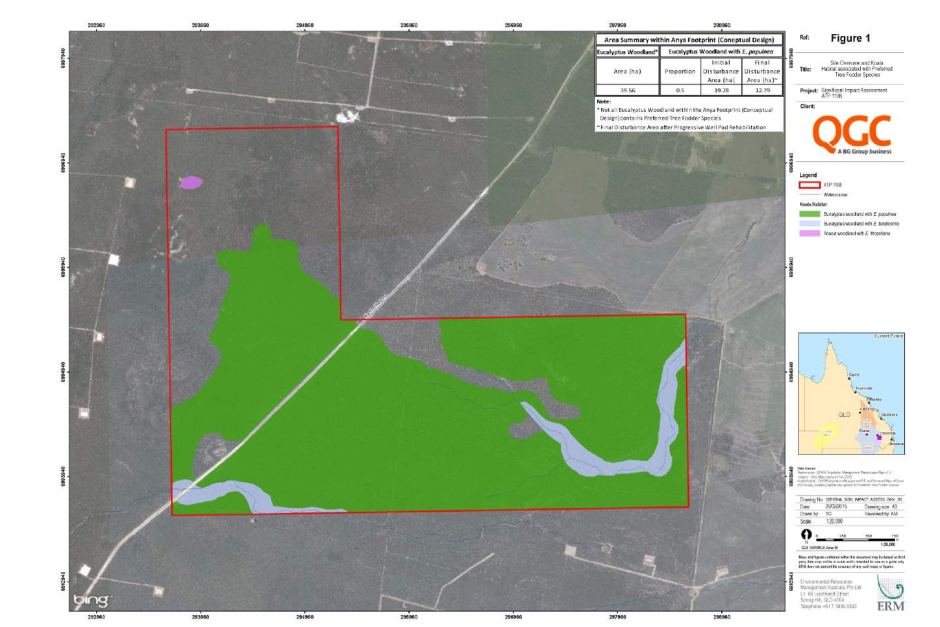

MARIAN WILKINSON: Six years ago, when East Coomera was already earmarked for massive development, Dr Steve Phillips was belatedly hired by the Gold Coast City Council to survey the area for koalas.

To the Council’s alarm, he discovered a rich habitat supporting 500 animals across Coomera and neighbouring Pimpama.

(Dr Steve Phillips and Marian Wilkinson walking down a bush track together)

DR STEVE PHILLIPS: It was very good koala habitat and in fact it still is koala habitat.

MARIAN WILKINSON: Many koalas lived right here, smack in the middle of what will be the next development phase, the town centre where Westfield is supposed to build a giant shopping mall.

MARIAN WILKINSON: What’s to become of it?

DR STEVE PHILLIPS: Bitumen, concrete, shopping centres and buildings.

MARIAN WILKINSON: It was clear to Phillips that planning decisions made years earlier meant no-body would stop the development. The only option open to save the koalas was to move them out.

DR STEVE PHILLIPS: Despite the fact that we had presented a good body of very new information it essentially amounted to nothing, apart from the need, obviously, to mount a rescue mission, because there was potentially going to be a large tragedy here.

MARIAN WILKINSON: The man the Gold Coast hired to head that rescue mission is John Callaghan, a passionate scientist who once worked with Phillips.

(Footage of John Callaghan and a tree climber preparing to climb a tree to rescue a koala)

Callaghan and his team have so far moved around 100 koalas out of the East Coomera development zone. Now they’re preparing to move more, including some from this site where a residential estate with 130 marina berths is planned.

(Footage of tree climber climbing up tree)

This is an extraordinary and risky experiment called wildlife translocation. And it’s fraught with stress for both the koalas and the scientist.

JOHN CALLAGHAN, KOALA CONSERVATION PROJECT MANAGER: I would never want to see koalas moved out of an area again to allow a development to occur because it’s not the best outcome. But in a situation like this, where there’s really – the other alternative is to do nothing, to allow the intensive development to occur. We know, we’ve seen it up and down the east coast, what happens to the animals where they are displaced.

(Sound of jackhammer)

MARIAN WILKINSON: The distant jack hammering is a constant reminder of why we’re all here.

But catching a koala even before you take away their home is no easy job.

(Footage of team trying to catch Nita)

This is Nita. She’s been caught before and didn’t like it. And now she’s got a joey.

The tree climber must use an adjacent tree tall enough to get above Nita and unfurl a billowing flag to essentially scare her into coming down.

John Callaghan armed with another flag goes to the base of her tree to try to steer her into his bag.

JOHN CALLAGHAN: Come on girl, come on girl, come on little one. Come on girl, in you go, there’s a girl, there’s a girl. Come on, come on.

(Nita squeals and grunts as she’s caught and put in bag.)

Got it, yes….

MARIAN WILKINSON: It’s not exactly koala whispering.

JOHN CALLAGHAN: Good work, she was quite lively there at the end

MARIAN WILKINSON: Translocating koalas to make way for developers is usually banned in South East Queensland.

But there can be exceptions: if it’s part of a scientific research project on the translocation of wildlife.

And that was the solution in Coomera, allowing the state government to grant a scientific permit to remove the koalas.

JOHN CALLAGHAN: We’re really looking at the science that underpins relocation programs, what we need to do to make them as successful as they possibly can – can be over a longer time frame. It’s a massive project for us.

MARIAN WILKINSON: So all up there’ll be about 200 koalas moved out of East Coomera?

JOHN CALLAGHAN: That’s correct.

MARIAN WILKINSON: After Nita gets a shot to calm her, she’s ready to play her part in this scientific project.

(Footage of team setting up mobile surgery and lab)

(Sound and footage of children playing AFL in the background)

On the edge of Coomera’s community sports field a mobile animal surgery and research lab is set up with the help of leading koala vet, Jon Hanger.

(Sound of heart monitor beeping)

Under anaesthetic Nita and her joey first get a health check.

JOHN CALLAGHAN (checking Nita): It’s little hand there anyway. That’s about as much as we are going to see I think.

MARIAN WILKINSON: Her paws are shaved to take blood tests.

Then her eyes are swabbed for signs of Chlamydia, a sexually transmitted infection widespread in Queensland koalas that can affect fertility.

JOHN CALLAGHAN: We’ve just finished off the last of her Chlamydia swab tests that we wanted. So some of those we’ll run here today so that we make sure she doesn’t have an active infection in either of her eyes or her uro-genital tract at the moment.

MARIAN WILKINSON: The research and translocation project has been financed by the Gold Coast City Council. And it’s proud of its solution to Coomera’s koala problem.

TOM TATE, GOLD COAST MAYOR: We’re here to be fair to the developers and we’re here to be fair to the koalas.

MARIAN WILKINSON: Mayor Tate.

TOM TATE: Hi Marian how are you?

MARIAN WILKINSON: Good to meet you.

TOM TATE: Welcome.

MARIAN WILKINSON: Come and sit down.

TOM TATE: Thank you.

MARIAN WILKINSON: For the busy new mayor of the Gold Coast actually stopping the development at Coomera is unthinkable at this stage.

TOM TATE: I mean there’s litigation and loss of their profit. So it’s not it’s not the uh solution that we – we don’t want to fight with people. If the relocation is doable, and after monitoring this 100 koalas that the survival rates is good as per natural attrition and that they’re happy with it, then it gives me heart that we can continue on with that and without any conflict with the with the urban developers.

(Footage of the Lower Beechmont Conservation Area)

MARIAN WILKINSON: But translocation is fraught with dangers. Many Coomera koalas were taken here, 15 kilometres from their home to the Lower Beechmont Conservation Area behind the Gold Coast.

Fourteen of those translocated koalas were killed by wild dogs.

JOHN CALLAGHAN: Which has been a real eye opener for us. It’s been very sad to see that happen. It certainly wasn’t anticipated going into the program.

VOICEOVER: The dogs have mostly been dealt with, but the deaths have raised questions over the Coomera project.

And one of Queensland’s leading koala experts is sharply critical of it.

PROFESSOR FRANK CARRICK, KOALA SCIENTIST, UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND: Well, whether or not it’s a genuine scientific project, I mean it still is a Japanese scientific whaling approach to dealing with the problem of bad planning decisions over east Coomera. Now you know they’ve been coming down the track for a while but it wasn’t till very late in the piece that somebody said ‘oops there are a lot of koalas there, what on earth are we going to do about them?’

MARIAN WILKINSON: It’s a charge John Callaghan adamantly rejects.

JOHN CALLAGHAN: We’re giving them a really good chance now. And clearly it can work. It’s not true at all to say that we are, you know, just culling them and likening that to whaling, because we are giving them a realistic chance of surviving.

JON HANGER, KOALA VETERINARIAN: Translocation is not something I want to do. It’s something that I’d prefer to do rather than leave them to die when the bulldozers roll or in the aftermath of the loss of their habitat. Because in effect when we destroy their habitat, we’re forcing them to move anyway. And I’m saying we should be doing that in a scientifically robust and valid way, rather than just saying look, it’s up to you guys, we’ve destroyed your habitat, now you find somewhere safe to live.

MARIAN WILKINSON: You only have to drive 50 kilometres from Coomera to understand the scientists’ dilemma. When koalas try to live where we want to live, we usually win out.

(Footage of Koala Coast residences)

(Sound of dog barking)

This is part of what’s called the Koala Coast, south east of Brisbane. People flocked here in the last 20 years, bringing with them their dogs and their cars.

By 2004, local koalas were dying at a rate of close to 300 a year just from being run over. Hundreds more were killed by dogs or driven out by development.

(Footage of Marian Wilkinson and Sean FitzGibbon walking along urban streets in Redlands)

SEAN FITZGIBBON, KOALA RESEARCHER, UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND: We’re right in the heart of the Koala Coast here in Redlands, and it’s one of the strongholds of koalas in South East Queensland.

MARIAN WILKINSON: Koala researcher Sean FitzGibbon worked with the local Redland Council to protect the koalas trying to hold on in the parks and remnant bushland after the houses appeared.

SEAN FITZGIBBON: I spotted one earlier this morning so we’ve got a young female in this tree, right at the edge of the road here, hanging on in the edge of suburbia really.

MARIAN WILKINSON: And you’re the one who can do the spotting, so you tell me where I can find it.

SEAN FITZGIBBON: This one is quite concealed in the vegetation, but there’s a young …

MARIAN WILKINSON: Oh right.

SEAN FITZGIBBON: … it looks like a young female sitting on the Tallowwood branch up there.

MARIAN WILKINSON: Until the last few years, the koala population here was in free fall.

SEAN FITZGIBBON: I like to think the Koala won’t be functionally extinct in the Koala Coast. I think despite that big decline, we still have significant large chunks of bushland that have been set aside as reserves, and I think koalas will always persist in those areas.

It’s the areas that aren’t protected, and there’s still a lot of that in South East Queensland, where we’re going to see continued declines.

(Footage of koala in tree)

MARIAN WILKINSON: The bleak statistics show koalas on the Koala Coast crashed by a massive 65 per cent in the decade to 2008.

FRANK CARRICK: The population has absolutely collapsed from 6,000 to 7,000 odd animals down to a couple of thousand animals over a decade or less. It just can’t keep going down at that rate. It means that there will be functional extinction of the koala, unless that decline is stopped and then subsequently reversed, in the next few years.

MARIAN WILKINSON: Do you have a crisis over the koala in Queensland?

ANDREW POWELL, QUEENSLAND ENVIRONMENT MINISTER: Look, there is no denying that surveys in the mid 90s to surveys done in around 2008, on the Koala Coast in particular, show that the numbers of koalas declined significantly. What is encouraging, the most recent survey showed that the numbers have largely stabilised.

And that does suggest that the policies that the government has taken, and potentially the work that we’re going to invest as a new government in terms of koala protection, we’ll see that stabilisation continue and hopefully turn around and improve.

FRANK CARRICK: No, the data don’t actually show that. What the data show are that the really catastrophic rate of decline has probably levelled off to some extent. We won’t know till the next survey of whether it’s still continuing to go down but at a slower rate.

MARIAN WILKINSON: South East Queensland once had a thriving koala population. But since 1997 koala hospitals here have recorded around 15,000 deaths.

The state government was forced to list the koala as a vulnerable species in this region eight years ago.

And despite laws that protect koala habitat and funding to buy prime habitat, some is still being flattened for development which was earmarked years or even decades ago.

(To Andrew Powell): Why can’t you stop it?

ANDREW POWELL: I think we have achieved an effective balance through the policy that we’ve adopted and that we’re going to take forward. That is that the best koala habitat has been mapped, it’s been set aside in strategic corridors, it’s been site specifically located and it is protected.

TONY BURKE, FEDERAL ENVIRONMENT MINISTER: What they claim is sufficient is a process where we’ve been heading down a track where if in Queensland you want to see a koala you’re going to have to go to a wildlife park. They’re been going down a path where we won’t find them in the wild over time.

Now that is not good enough. Absolutely not good enough. And yes, it does mean an extra layer of regulation, but that’s why we have environmental regulation. And this is not some weird species that noone’s heard of, you don’t get more iconic than this one.

MARIAN WILKINSON: Now koalas in Queensland and New South Wales are on the National Threatened Species List Canberra has the power to intervene.

But Queensland is calling it more green tape.

ANDREW POWELL: The biggest impact in the Federal Government’s listing is here in Southeast Queensland, where we’ve already got a very stringent planning regime, where we’ve already got a very strict policy around koala protection. And what potentially we will see is a huge number of development applications that are assessed under our very strict guidelines also having to go to Minister Burke and his department for their consideration.

TONY BURKE: In terms of how many will require a federal approval, the evidence so far where there’s been one that’s actually kicked into the federal threshold means that there’s a bit of hyperbole in the arguments that the Queensland government’s being put.

MARIAN WILKINSON: Because the federal listing covers all Queensland it could also affect the state’s huge mining expansion.

(Photographs of land cleared for mining)

These photographs supplied to Four Corners show how large swaths of koala habitat were flattened as mine sites many kilometres wide, were cleared, leaving this koala literally hanging on for dear life.

(Photograph of Koala hanging on to tree branch)

The good mining companies employs diligent koala spotters, but some are much less careful.

JON HANGER: I guess the average person in the street has a view that these animals scamper away in front of the bulldozers and go and find somewhere else to live. But the cruel reality is that most of them die, not necessarily immediately, some of them you know have limbs torn off and suffer horrific crushing injuries. Others will simply starve to death. Others will just be displaced and have no shelter.

MARIAN WILKINSON: The loss of koala habitat is not only culling animals in Queensland and New South Wales. It’s stressing the survivors, and hundreds are being brought into koala hospitals.

(Footage of Bungee being taken into koala hospital at Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary)

MICHAEL PYNE: Ok Bungee, in you go buddy. That’s the lad. Well done. Alright buddy, can we spin you around and have a look at your leg?

VOICEOVER: Michael Pyne has been a vet at the busy Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary Hospital on the Gold Coast for over a decade.

MICHAEL PYNE: Alright mate, well done. Let’s have a look over the rest of you hey?

MARIAN WILKINSON: While Bungee here has a leg injury from being caught in a fence, Dr Pyne is these days seeing many koalas struck down by disease.

MICHAEL PYNE: I think there’s been a trend over the last two or three years where we’re seeing more and more disease. We’re certainly still seeing these koalas come in being hit by cars, being attacked by dogs, and these trauma related ones. But we’re certainly seeing more disease you know as a percentage and more advanced disease.

MARIAN WILKINSON: Vet Jon Hanger is now researching a retrovirus common in koalas. Contentiously, he argues it could also be one of the triggers for the high disease levels.

JON HANGER: One of the major worries is that we see so many ill koalas in Queensland and New South Wales.

We haven’t definitively been able to blame the retrovirus. Certainly there’s a swag of circumstantial evidence. But clinically we see leukaemia, which is very similar to childhood leukaemia in human children; we see a range of bone marrow disorders that cause the koalas not to produce red and white blood cells; and we also see a condition like AIDS in humans in that the koala’s immune systems don’t seem to work properly. They die from infections that they should be able to resist.

MARIAN WILKINSON: Whatever the role of the retrovirus, high levels of koala disease are also being blamed on stress caused by the loss of their habitat.

(Footage of tourists having their photos taken with koalas at Lone Pine)

AMERICAN TOURIST (preparing to have photo taken): This is so exciting. This like the most exciting thing I’ve ever done!

MARIAN WILKINSON: At Brisbane’s famous koala sanctuary, Lone Pine, few of the tourists realise the struggle now underway to make sure koalas will also survive in the wild.

WOMAN TAKING PHOTO: Awesome!

AMERICAN TOURIST: Thank you so much.

WOMAN TAKING PHOTO: Not a problem.

AMERICAN TOURIST: Thanks very much. (Koala holds on to her) Hey, I’m a tree!

(Laughter)

MARIAN WILKINSON: But this special place is itself a tragic reminder of how easily we can push the koala to the brink of extinction.

Today koalas are threatened by development and disease. But last century it was the hunter’s bullet.

It’s only recently that I discovered that this sanctuary was set up in the aftermath of one of the worst wildlife slaughters in Queensland’s history. It was called Black August in 1927 when the Queensland Government declared open season on the koala. It created an outcry all over Australia, and especially here in Queensland where it help topple the Labor government.

(Archive photograph showing trailer piled high with koalas)

The koalas were slaughtered for their fur to make Stetson hats and ladies gloves.

(Archive photograph of koala skins laid out)

And some 600,000 pelts were collected in that one month.

(Archive photograph of hunters in front of row of koalas hung on a stick)

But early last century it wasn’t just in Queensland where hunting was rampant.

(Archive photograph of hunters in front of koala skins tacked onto a wall)

In Victoria, the koala fur trade almost wiped them out; leaving only a few pockets of survivors.

(Archive photograph of a koala hunter bush camp)

The strange story of how Victoria brought its koala back from the brink can be found over on a quiet island in Western Port Bay, 60 kilometres south east of Melbourne.

The only way you get to French Island is by ferry, and that’s the way some locals still like it.

(Footage of Lois Airs feeding her sheep)

LOIS AIRS, FRENCH ISLAND LOCAL: My great grandparents there was the salt industry and collecting of seagrass went through the four, four generations.

MARIAN WILKINSON: Lois Airs remembers the story of how the first koala joeys were brought to French Island in the 1890s when the animals were being slaughtered on the mainland.

(To Lois Airs): Can you give us the romantic version?

LOIS AIRS: Yes, that they were a present for a lady. A man sort of wooing a lady brought the first two over. And so that started off the koala population.

(Footage of a koala in a tree on French Island)

MARIAN WILKINSON: Because the koalas arrived as joeys they were free of Chlamydia, the sexually transmitted infection many believe controls koala populations in the wild.

Disease free, the population boomed. And being twice the size of their northern cousins, they ate themselves out of a home.

LOIS AIRS: Local people lobbying governments to have koalas taken away, just so you didn’t see starving koalas, skinny koalas. Dad said he’d rather shoot them than see them not being able to find enough food.

MARIAN WILKINSON: The solution to the ‘over browsing’ as it was called was to start translocating the koalas to other islands and state parks on the mainland.

(Parks officers catching a koala on French Island)

STEVE COUTTS, PARKS OFFICER: Clear the area a bit.

MARIAN WILKINSON: And so from a handful of French Island joeys, Victoria was repopulated with koalas.

(Koalas being put in cage for transportation, grunting)

PETER MENKHORST, FORMER HEAD, KOALA MANAGEMENT STRATEGY, VICTORIA: This has been a huge wildlife translocation programme that’s gone on for literally 90 years, and more than 25,000 koalas have been removed from patches where there were too many koalas and placed into mainland habitats where there were fewer koalas or none. And in that way, over that 90 year period, we’ve repopulated Victoria with koalas. And pretty well now all the potential koala habitat in Victoria is occupied by koalas.

(Footage of Marian Wilkinson and Scott Coutts in bush on French Island)

MARIAN WILKINSON: Is this one of the trees that you were talking about in here?

SCOTT COUTTS, PARKS OFFICER: Yes, yeah, fortunately some of it’s still alive but most of it’s been destroyed by koalas keeping on eating. It is one of their favourites.

MARIAN WILKINSON: Parks’ officer Scott Coutts has been working on French Island for over two decades.

He’s proud of the operation here that gave Victorians back their koalas.

But when you manipulate nature for almost a century, it can have profound consequences.

The French Island koalas in time overpopulated some of the parks on the mainland and the other islands. And they began to starve again.

The Victorian government, anxious for a solution to the overpopulation, began experiments in surgical sterilization. But these were stopped after some terrible death rates.

It settled, instead, on implanting female koalas with contraceptives.

SCOTT COUTTS (demonstrating how contraceptive is implanted): This is the actual this is called a trocar or implanting needle. That implant is inside that. Once the small incision’s made, the vet then pushes that through and it’s all done very all sterile.

This one has been out of the packet for a while, and then that goes and sits inside the koala.

With the anaesthetic machine they can basically be released within an hour or so.

MARIAN WILKINSON: But last October, after they were translocated to bushfire affected parks on the mainland, some female koalas were found starving or dead.

Earlier this year, the Victorian government quietly suspended its translocations of koalas from French Island.

PETER MENKHORST: Most recently, just last spring, there was a number of animals that were found in a compromised position after release and they’ve been taken into care.

MARIAN WILKINSON: Do you think that has an impact on the government with ending the translocation programme or do you think it’s…

PETER MENKHORST: Oh certainly yeah.

MARIAN WILKINSON: Yeah…

PETER MENKHORST: Yeah. I mean we don’t want to be involved in any management that causes stress and harm to wildlife.

(Footage of Southern Ash Wildlife Shelter)

COLLEEN WOOD, SOUTHERN ASH WILDLIFE SHELTER: The females seem to really be debilitated and they are not lactating for their joeys.

MARIAN WILKINSON: Colleen Wood is a long time koala carer in Victoria’s Gippsland. She began sounding the alarm last year when koalas translocated from French Island began arriving at her shelter.

(to Colleen Wood): She’s from French Island?

COLLEEN WOOD: She is. She’s a translocated koala from French Island to the Bunyip State Park.

MARIAN WILKINSON: And what condition was she in when you got her?

COLLEEN WOOD: She was quite anaemic. She was malnourished. She was fully vet assessed before she actually came to the shelter here and underwent some intravenous fluids. And now we’ve just been feeding her up a bit and getting her back on track.

MARIAN WILKINSON: Did she have the hormone implants?

COLLEEN WOOD: She did. She actually had two hormone implants.

MARIAN WILKINSON: Are they still there now?

COLLEEN WOOD: We’ve actually taken them out of her to get her back on track, and we did that with the consent of the DSE, because we had . . .

MARIAN WILKINSON: The department?

COLLEEN WOOD: Yeah, because we had some issues with it.

MARIAN WILKINSON: But Colleen Wood is worried about a much bigger problem.

Apart from a few isolated populations, nearly all Victoria’s koalas go back to the tiny gene pool on French Island. And she believes she’s beginning to see serious signs of long term inbreeding, including genetic abnormalities.

(To Colleen): Tell us what’s wrong with Miley? Can we have a look at her?

COLLEEN WOOD: Yeah, we can. I’ll actually grab her because she’s fairly resilient.

She actually came in as a joey. She’s quite bigger now, but you can see the marked differences with her with her eyes are quite pinny…

MARIAN WILKINSON: Very small eyes.

COLLEEN WOOD: … she’s got a very rounded face. You feel her lack of muscle tone, even though she’s in this pen. Like she’s just…

MARIAN WILKINSON: Oh yeah!

COLLEEN WOOD: And a koala of this size, you shouldn’t be able to pick up. Like, you know, she should be quite fightie, flighty and have some fight response, which she isn’t showing.

MARIAN WILKINSON: And what do you think’s going on here?

COLLEEN WOOD: It’s definitely genetical issues. Like these guys were actually translocated from French Island onto the Sandy Point area and I believe the population crashed in the 80s. And the genetics are just – you can see, like they’re not good. They are not good.

MARIAN WILKINSON: No.

COLLEEN WOOD: These animals do not thrive.

MARIAN WILKINSON: Right now the Victorian government believes their koalas are widespread. But there are serious questions over how the inbred Victorian koala will adapt to future threats.

And the most deadly of these, say the experts, is likely to be climate change.

PETER MENKHORST: We’ve got a lot of koala populations across the state that seem to be fairly stable but we don’t really know. And given climate change, I think that’s the big unknown in all of this, so yes, it’s very possible that things could flip over and populations decline in future.

MARIAN WILKINSON: To understand the terrible effect of extreme temperatures and drought on koalas, we travelled to the township of Gunnedah, in north west New South Wales.

Gunnedah proudly claims to be the koala capital of the world. Amazingly, koalas thrived here even while their numbers collapsed by a third across New South Wales.

That was, at least, until a deadly run of heatwaves in 2009.

JOHN LEMON, NSW OFFICE OF ENVIRONMENT: This was some of the least productive soil on the place, and basically decided to turn it back into habitat for wildlife and koalas.

MARIAN WILKINSON: John Lemon and Dan Lunney from the New South Wales Environment Department, were carefully tracking the koala recovery in Gunnedah.

It came about after local farmers were encouraged to plant koala friendly eucalypts across degraded farmland.

DR DAN LUNNEY, PRINCIPAL RESEARCH SCIENTIST, NSW OFFICE OF ENVIRONMENT: We’d been radio tracking for two years by this stage, we’d never seen this before.

MARIAN WILKINSON: But in late 2009 John and Dan began to see many koalas dehydrated and dying at the base of trees.

DR DAN LUNNEY: There was a period in late November, then December where the temperature day after day, in the drought, was over 35, over 40. And so if there’s no moisture in the leaves, no moisture in the ground, the koala sitting at the bottom of the tree.

That’s not unusual to see koalas at the bottom of the tree, what’s unusual is when you go up and you spray the water on the nose of the koala and it reaches out for you. A wild koala reaching out for help.

MARIAN WILKINSON: At this tree, near the local research centre, Dan Lunney captured on camera, a remarkable record of the impact of those extreme temperatures.

He and John had pulled up to help a severely dehydrated koala.

JOHN LEMON: She was just literally limp at the bottom of the tree and her head popped up as soon as she heard the vehicle but didn’t move.

(Stills from video of dehydrated koala rescue are displayed)

I was spraying her initially, and then as soon as she felt that moisture on her face she came to seeking the source of the water.

(Still of koala reaching out for water bottle and drinking)

MARIAN WILKINSON: But you could feel those little claws there.

(Still of Koala drinking from bottle with her claws dug into John Lemon’s hand)

JOHN LEMON: Oh, yeah she’d actually penetrated my skin and there was a few little droplets of koala induced blood and mayhem. But anyway, no, she was just desperate.

MARIAN WILKINSON: You can see she still looks utterly exhausted in that picture.

JOHN LEMON: Oh yeah.

(Still of koala with her tongue out after drinking from bottle)

DR DAN LUNNEY: It looks like a tame animal doesn’t it?

JOHN LEMON: Mm.

DR DAN LUNNEY: That’s a wild animal.

You wouldn’t expect that at all. If you walked over to a koala you wouldn’t expect to be able to walk over and take a photograph close up. It’d be up the tree, behind the tree, into the leaves.

(Still of koala drinking from water bottle)

So this tells us there is a crisis for this koala. And when we saw it property after property we knew we had a across, across the landscape.

Our estimate from our own koalas we were studying, from the koalas we saw on the farms when we were talking to farmers was about a quarter of the population died over a few weeks.

The other consequence was that the chlamydia which was just present in the population but only by sampling tissue samples, but it wasn’t clinically evident, became manifest the following year and the percentage rose to about 30 per cent of the population. Which means as females won’t breeding, not only that they’ll be in distress and a sexually transmitted disease, so it could increase. So not only is the death rate increased but the birth rate is decreased. And that is a combination which pushes a population down.

MARIAN WILKINSON: We know the natural cycle of flood and drought creates great booms and busts in wildlife populations.

But what worries scientists is whether frequent bouts of extreme temperatures brought on by climate change will completely drive out local koalas from some areas.

DR DAN LUNNEY: Koalas don’t live underground, they can’t fly away, they can’t hibernate. They’re sitting in the top of the trees, so if there’s gonna be a scorcher day during a drought, they’re going to feel it. What every animal wants is to survive each particular day. So even if the temperature rises one or two degrees, that’s not the issue, the issue is the increasing frequency of very hot days in a drought. And that’s the crisis for koalas when you’re in the western half of their range in New South Wales and Queensland.

MARIAN WILKINSON: But the Gunnedah study also gives hope for the future.

Getting the farmers and the community replanting the local landscape with koala friendly trees does make a big difference.

Not only do they bring back koalas back in good times, but they can also offer them some protection during the bad times.

DR DAN LUNNEY: The trees that are important are the trees next to the gully lines that have got deep roots, that are taking up moisture even in drought conditions. So it’s those trees that are crucial refuges during the most intense periods of drought with heatwave.

(Footage of Koala in sanctuary)

KEEPER: So this is Occy, one of our little boy koalas …

TOURIST: So soft!

KEEPER: He’s about 18 months of age.

MOTHER: Hey Savannah!

MARIAN WILKINSON: With his spoon nose and fluffy ears, the koala is Australia’s most loved native animal. A draw card at every wildlife park and zoo.

(Footage of people having their photograph with Occy.

KEEPER: Do you want to give him a cuddle Savannah? Gentle.

(Savannah cuddles Occy)

MOTHER: Good girl!

Say bye bye! Wave bye bye, Occy, wave bye bye

MARIAN WILKINSON: But our challenge is to ensure the koala will survive not just in sanctuaries but in the wild.

STEVE PHILLIPS: Until we apply the basic principles that we all know about that apply to this animal: leave its food trees alone, keep the dogs away from them, keep the roads and the cars away from them and just let them live in peace. And find that balance between enough land for them, enough land for us, then we’ll have a balance.

(Footage of Nita being checked at mobile hospital and research centre in Coomera, Gold Coast)

MARIAN WILKINSON: But until now, when it’s comes down to their homes or ours, the balance is usually tipped against them.

For scientists like John Callaghan, preparing koalas to be taken from their home is not a task he enjoys.

(John Callaghan preparing to release Nita)

JOHN CALLAGHAN: Look after yourself, darling.

Ok Mark.

MARIAN WILKINSON: Tonight at least he can take Nita home.

JOHN CALLAGHAN: So we’re going to put her up this tree right there. Just there.

MARIAN WILKINSON: But only until the developers are ready to roll.

(Footage of Nita climbing up tree)

JOHN CALLAGHAN: She’s going to get upset.

(Sound of Nita crying)

KERRY O’BRIEN: It’s the classic environmental dilemma, how best to find the middle ground that serve human priorities while protecting the fundamental cornerstones of the natural world.

End of transcript

Background Information

WEB SPECIAL

Koala Crunch Time Web Special – For more information, plus interviews and video, images and statistics, plus a brief history of the koala fur trade, visit the Koala Crunch Time Web Special on ABC News.

KEY REPORTS ON KOALA POPULATIONS

Listing advice for Phascolarctos cinereus (Koala) | Threatened Species Scientific Committee | 2012 – Advice to the Minister for Environment from the Threatened Species Scientific Committee regarding the listing of the koala under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. See Table 1 on page 13 for mortality statistics of koalas in SE Queensland. [PDF 401Kb]

Koala Coast – Koala Population Report 2010 | Queensland Dept of Environment – The Queensland Government has monitored the Koala Coast koala population since 1996, investigating koala distribution, abundance, comparative ecology and population dynamics. This continues to be the most detailed regional monitoring study of koalas undertaken to date in Queensland or indeed elsewhere in Australia. Read the report. [PDF 1.33Mb]

National Koala Conservation and Management Strategy 2009-2014 | Department of Environment | Nov 2009 – The strategy provides a national coordinating framework for plans and actions to conserve and manage koalas, many of which are already being undertaken by state and local governments. It will be coordinated by a cross-jurisdictional implementation team and regular engagement with a wide range of stakeholders, including researchers, local governments, conservation groups and developers. Download the report.

Species and Climate Change: More than Just the Polar Bear | IUCN Species Survival Commission | Dec 2009 – This report presents 10 new climate change flagship species, chosen to represent the impact that climate change is likely to have on land and in our oceans and rivers. [PDF 4Mb]

“Black August” Queensland’s Open Season On Koalas in 1927 | June 1993 – A thesis on the history of Black August, in Queensland 1927, written by Glenn Fowler. (PDF 301Kb)

FURTHER READING

Development blamed for ‘frightening’ surge in koala deaths | ABC News | 20 Aug 2012 – Wildlife experts have expressed fears the koala, which is now a threatened species on Australia’s east coast, is in serious danger because of urban development.

Koala Report | Australians for Animals | 20 Aug 2012 – In 1994, Australians for Animals (AFA) presented an historic scientific submission to the US government supporting the listing of the Koala. Read more.

Sanctuary’s injured koala numbers rising | ABC News |17 Aug 2012 – The number of injured koalas being admitted to a Gold Coast animal hospital has more than doubled in just 12 months. The Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary has treated more than 200 koalas this year.

Farmers against council koala plan | The Norther Star | 27 Jul 2012 – NSW Farmers Association has expressed concerns about Ballina Shire Council’s moves to develop a koala plan of management.

Ballina to consider own koala plan | The Norther Star | 25 Jul 2012 – With the koala recently listed as a threatened species, Ballina Shire Council could soon join the growing list of councils preparing a Koala Plan of Management.

Saving the koala – a genetic approach | University of Sydney | 17 Jul 2012 – Following the recent listing of koalas as a threatened species in NSW and Queensland, a team of scientists has received federal funding to undertake cutting-edge research to help with koala conservation.

Logging the South East Forests: Part 1 Koala Survey | ABC Local | 3 Jul 2012 – It is the most controversial issue in south east NSW, muddied by spin from both sides, and a stage for bitterly opposed politics. The Regional Forest Agreements of the late 1990s were intended to find a middle ground between the interests of conservationists and forest industries yet protests continue. This series will explore how Australia’s south east forests are now logged and why these operations are disputed.

Gunnedah may hold key to reversing koala decline | Australian Geographic | 26 Jun 2012 – Home to one of the only growing koala populations in NSW, Gunnedah shows that land restoration can be a win-win.

Koala listing a threat to building industry, says Campbell Newman | The Courier Mail | 1 May 2012 – Premier Campbell Newman fears the Gillard Government’s decision to list Queensland koalas as vulnerable needlessly duplicates the “green tape” threatening the state’s struggling construction sector.

Racing to Rescue Koalas | National Geographic | May 2012 – Koalas are under siege. Can Australia rescue them? A feature essay by Mark Jenkins.

Koala listing offers no protection from logging | ABC Local | 30 Apr 2012 – The newly announced listing by the Australian Government of koalas as a vulnerable species in NSW will not provide additional protections in areas logged by Forests NSW.

Our Fading Emblem | The Courier Mail – Qweekend | 14 April 2012 – The relentless march of industry and infrastructure, coupled with debilitating disease, could see Queensland’s koalas die out within decades. By Matthew Fynes-Clinton. [PDF 2.67Mb]

Koalas to feel the heat with climate change | Australian Geographic | 5 May 2011 – A Senate inquiry has been told that the koala needs national protection to help shield it from climate change.

AIDS-like virus new threat to koala | Australian Geographic | 25 Feb 2010 – A virus that may weaken the immune system of koalas, similar to HIV in humans, is a new “wild card” among threats facing the species and nearly all koalas in Queensland could already be infected.

Read: “Koala, Origins of an Icon” by Dr Stephen Jackson (2007) published by Allen and Unwin.

INFORMATION & ADVOCACY

Animals Australia – Dealing with animal welfare and animal rights issues. www.animalsaustralia.org/

Australians for Animals Inc is an Australian charity with a long history of action in environmental and animal rights campaigns within Australia and overseas. www.australiansforanimals.org.au/

The Australian Koala Foundation – The principal non-profit, non-government organisation dedicated to the conservation and effective management of the wild koala and its habitat. www.savethekoala.com/

Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary – A non for profit wildlife sanctuary, Gold Coast, Queensland. www.cws.org.au/

Get Up! Campaign – An Australian icon at risk. Read more about the Get Up campaign. www.getup.org.au/…/koalas-petition/protect-koalas

Koala Action Pine Rivers Inc– A volunteer not for profit group made up of individuals concerned about the long-term survival of the koala population in the Moreton Bay Regional Council District. koalas.kumbartcho.org.au/

The Koala Action Group Qld (KAG) is a community group working to help koalas in our unique Redland environment. www.koalagroup.asn.au/

Koala Central is designed to be to be a central portal for information, research, opinions and discussion about koalas across Australia. www.koalacentral.com.au/

Koala Conservation Program | Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary – Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary is pleased to be partnering with Gold Coast City Council and Wildcare Australia to prepare a koala conservation plan for the Elanora-Currumbin Waters area. More information online. www.cws.org.au/…/koala_conservation_program/

The Koala Research Network is an independent group of Australian researchers concerned with ensuring the long term viability of koala populations in the wild. www.uq.edu.au/krn/

Koalaresearch.net.au – Information and research. www.koalaresearch.net.au/

Lone Pine Koala Sanctuary – Lone Pine Koala Sanctuary in Brisbane, Australia, is the world’s first and largest koala sanctuary. www.koala.net/

Minding Animals International (MAI) provides an avenue for the transdisciplinary field of Animal Studies to be more responsive to the protection of animals. www.mindinganimals.com/

RSPCA Australia is a community based charity that works to prevent cruelty to animals by actively promoting their care and protection. www.rspca.org.au/

Save the Australian Koala | Facebook – Official Facebook page of the Australian Koala Foundation. www.facebook.com/SavetheAustralianKoala

Southern Ash Wildlife Shelter – A not for profit, volunteer-run wildlife shelter, Gippsland, Victoria. www.samthekoala.com.au/

Wildcare Australia is a non-profit organization located in South East Queensland dedicated to the rescue and rehabilitation of native wildlife. www.wildcare.org.au/

WATCH RELATED ABC REPORTS

Koala Heatwave | Catalyst | 14 April 2011 – Without human intervention, this species may be in serious trouble. Koalas in Gunnedah are the lucky ones. A couple of decades ago, local farmers like John Lemon planted thousands of trees to fight salinity…

Great Barrier Grief | Four Corners | 3 Nov 2011 – An investigation that asks if the Great Barrier Reef is in danger from massive coastal development brought on by the resources boom in Queensland.

A Bloody Business | 30 May 2011 – An explosive expose of the cruelty inflicted on Australian cattle exported to the slaughterhouses of Indonesia. Flash Video Presentation

![]()

![]() The Russian Peace Threat examines Russophobia, American Exceptionalism and other urgent topics

The Russian Peace Threat examines Russophobia, American Exceptionalism and other urgent topics

1 Why the Viral Video of a Young Chimpanzee Scrolling Through Instagram Isn't So Cute

1 Why the Viral Video of a Young Chimpanzee Scrolling Through Instagram Isn't So Cute  2 Former Hornbill Poacher Becomes a Wildlife Ranger

2 Former Hornbill Poacher Becomes a Wildlife Ranger  3 Success! Norwegian Air Has Dropped Its Sexist Dress Code

3 Success! Norwegian Air Has Dropped Its Sexist Dress Code  4 Why We Should Start Saying 'Climate Crisis'

4 Why We Should Start Saying 'Climate Crisis'  5 This Endangered Turtle is Making a Comeback

5 This Endangered Turtle is Making a Comeback

Amazing good news! And I have mixed feelings about that fisherman who found her. At least he didn't take her home to eat her, so I guess that's a good thing.

It isn't surprising, and it certaily is gratifying - conservation and animal protection actually works.