The enormous majority of animals in the United States have no legal protection from violence and other cruelty. The shocking ways that factory farms treat them don’t break the law.

The fact that we have a federal Animal Welfare Act (AWA) creates the impression that there are at least some basic minimum standards that apply to all animals. That’s not true.

The law doesn’t cover animals raised for food. That is more than 10 billion individuals. It also leaves out 95 percent of the animals experimented on in research labs — probably another 100 million individuals. None of these beings has any legal protection from cruelty in the United States, except for a few isolated cases where a brave whistleblower has recorded extreme abuse and a couple workers have gotten slaps on the wrist.

The AWA is supposed to cover exhibited animals, like those in zoos. But even there it doesn’t do wonders. Tony the Truck Stop Tiger has been locked up alone, on exhibit in a barren cage at a truck stop, for just about all of his 13 years, amidst the din of diesel semis, the glare of floodlights that are never turned off, and the harassment of people who throw things at him to make him move. Lawyers and animal advocacy organizations, like the Animal Legal Defense Fund and PETA, have spent years doing what you do when someone breaks a law: going to court. Tony is still in his cage.

Unless the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) decides to enforce the law, for many animals it might as well not exist. No one else has this power. Some laws give individuals the opportunity to take law-breakers to court, but not the AWA. Only the USDA can sue. More often than not the USDA, which is more likely to be found helping farmers sell meat, doesn’t feel like going after people who make money exploiting animals. It is designed to be on their side. Protecting animals doesn’t merit even a mention in the agency’s mission statement.

So the people who really care about animals can’t help them through the courts. Judges agree with Congress that the courthouse doors should be shut to people who care about AWA violations. Since the Act isn’t intended to protect people, the courts won’t let people use it to sue.

The judges, at least, are being consistent. In every kind of lawsuit, not just cases about animals, only people directly affected by someone breaking the law can go to court over it. Here’s an example: say a contractor agreed to remodel my sister-in-law’s house, took her money and never did any work. No matter how angry I am, I can’t sue the contractor. Only the person directly affected can sue — in this case, my sister-in-law.

There is a catch-22 here: people can’t bring lawsuits on behalf of animals harmed by illegal conduct, but the animals can’t sue either, seeing as how they are animals and courts are very picky about that human/non-human distinction. In other words, when the truck stop makes Tony the Tiger’s life utterly miserable, people can’t sue for him, and he can’t sue for himself. Only the USDA can save the day, and generally speaking, it doesn’t want to.

This story illustrates how little the USDA wants to be in charge of protecting non-human animals. Congress gave the agency the job of making regulations that would sort out the details of the AWA. One of the first things the agency did in the area of animal experimentation was to declare that mice, rats and birds were not covered. That is 95 percent of the animals researchers use in labs.

Congress passed a law, and the president signed a law, to protect animals used for lab experiments. Then the USDA unilaterally decided that the law should protect only 5 percent of the individuals it was intended to help.

Here’s an illustration of why these laws are all but useless. The Animal Legal Defense Fund went to court and got a ruling that the USDA’s exclusion of mice, rats and birds from the AWA was not kosher and must be changed. Then a higher court said, “Wait a minute, ALDF. You’re humans. No one experimented on you. Get out of this courtroom.” Their victory was short-lived.

The Animal Welfare Act is a national law. What about the states? They could adopt laws to protect their own animals.

They could, but they usually don’t. In fact, the majority of states went out of their way to make sure cruelty to farm animals stayed legal. Since 1990, 36 states have adopted laws that make farms, including factory farms, immune to anti-cruelty laws. As David Wolfson points out in his book “Beyond the Law: Agribusiness and the Systemic Abuse of Animals Raised for Food or Food Production,” the fact that so many states felt compelled to set this immunity in stone demonstrates their understanding that if they didn’t, the things that happen to farm animals every day would be found unlawfully cruel.

So the AWA protects very few animals, and those only haphazardly, thanks in part to the USDA’s indifference. State laws can be even worse. As a result, billions of beings who feel pain, who have desires and who don’t want to die, are tortured and killed in the United States every year, while the government cheers it all on.

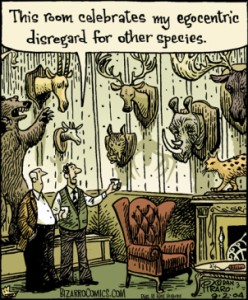

In addition some hunters have group memberships ($1500 membership fee) to elite clubs such as Safari Club International. (These clubs sponsor killing competitions. There are awards given to the most animals slaughtered. and they even keep a record book listing names of who killed what animal, when.)

In addition some hunters have group memberships ($1500 membership fee) to elite clubs such as Safari Club International. (These clubs sponsor killing competitions. There are awards given to the most animals slaughtered. and they even keep a record book listing names of who killed what animal, when.)

The Safari Club International protects the hunter via lobbying the US Congress to weaken the Endangered Species Act and petitioning the Fish and Wildlife Service not to list certain species as threatened or endangered.

The Safari Club International protects the hunter via lobbying the US Congress to weaken the Endangered Species Act and petitioning the Fish and Wildlife Service not to list certain species as threatened or endangered.