Bursting the Thatcher Bubble

—By David Corn, Mother Jones

Martin Argles/eyevine/ZUMAPress

Martin Argles/eyevine/ZUMAPressThe canonization of Margaret Thatcher began with nanoseconds of news reports that the former British prime minister and conservative icon had died at the age of 87. On MSNBC, my pal Chuck Todd remarked, “We lionize her over here.” There was insta-commentary about how she saved Britain from economic despair and the rest of the world from the Soviets (with some help from a guy named Ronald Reagan). Excess ruled. Two small examples: Elizabeth Colbert Busch, the Democrat running for Congress in South Carolina (and sister of Stephen Colbert) issued this statement: “When I talk to younger women about their careers, I point to Margaret Thatcher as a role model; she’s a tough consensus builder who cared about everybody and put her country’s fiscal house in order.” Rep. Steve Stockman (R-Texas) proclaimed,

Thatcher was no consensus builder; she was divisive. She set out to crush unions, privatize, undercut the social safety net (where she could), and push free-market policies that led to the deregulatory nightmares of the future. (Just watch Billy Elliot—or listen to the Clash.) She joined with Reagan in support of torturers and human rights abusers around the globe, as long as these folks were opposed to the Soviets. She called Nelson Mandela a “terrorist” and would not join the worldwide crusade against the racist apartheid regime of South Africa. (In 2006, Conservative Party leader David Cameron felt obliged to disown Thatcher’s and his party’s previous opposition to Mandela and his African National Congress.) She supported Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet. Her war in the Falklands struck many as an orchestrated stunt, not an act of necessity—though some have seen that military action as a noble blow against Argentina’s fascist junta (which the Reagan administration was supporting).

Her economic policies were harsh. She pushed the so-called poll tax—a tax to fund local government—that resulted in shifting the tax burden from the well-to-do toward lower-income Brits. This tax provoked riots—literally—and was so unpopular that her successor, John Major, replaced it. And as Bruce Bartlett, an economist who served in the Reagan administration noted two years ago, Thatcher shifted the overall tax burden from top to bottom. She cut the top personal income tax rate from 83 percent to 60 percent, but raised the lowest rate from 25 percent to 30 percent. To pay for her tax cuts, she nearly doubled the value-added tax from 8 percent to 15 percent. (Some American conservative economists howled about this.) As Bartlett put it, “Thatcher’s fiscal accomplishments were much more modest than many of today’s Republicans think.” (Here’s a quick assessment of her overall economic policies.)

A long obit in the Guardian by Michael White cites her “willpower and courage” and maintains that Thatcherism “changed the way Britons viewed politics and economics, as well as the way the country was regarded around the world.” But the article notes certain facts necessary for any balanced appraisal:

- She defeated the unions—especially the miners, in a series of challenges. But most deep-mine pits in England ended up closing.

- Her political career essentially ended when her own Cabinet told her that due to the unpopularity of her policies she should step down and allow another Conservative Party member to lead their party.

Thatcher was a historic figure. But that does not mean she was a great leader. (For a vitriolic assessment of her years in power, read this.) She was not the total conservative that American right-wingers have worshipped for years. She regarded climate change as a serious threat. Her government moved early against HIV/AIDS and outlawed corporal punishment. But in the aftermath of the demise of the Iron Lady, the first woman to become a British prime minister is generally being lauded from the US right and the middle as a hero for her country and the globe. This Thatcher bubble will not last forever.

support for the Khmer Rouge.

My Lai 45 Years Later—And the Unknown Atrocities of Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan

Remembering My Lai—

By Nick Turse, Global Research, March 19, 2013

Survivors recall their memories in 2000 of the mass killing of fellow villagers by U.S. soldiers during the Vietnam War, in My Lai, Vietnam. (Nick Ut/AP)

On the anniversary of the infamous My Lai massacre, Nick Turse recalls the numerous, less-well-known atrocities that marked the Vietnam War, and asks which atrocities from Iraq and Afghanistan we will be remembering in 45 years.

Forty-five years ago today, March 16, roughly 100 U.S. troops were flown by helicopter to the outskirts of a small Vietnamese hamlet called My Lai in Quang Ngai Province, South Vietnam. Over a period of four hours, the Americans methodically slaughtered more than 500 Vietnamese civilians. Along the way, they also raped women and young girls, mutilated the dead, systematically burned homes, and fouled the area’s drinking water.

In this day, I think back to an interview I conducted several years ago with a tiny, wizened woman named Tran Thi Nhut. She told me about hiding in an underground bunker as the Americans stormed her hamlet and how she emerged to find a scene of utter horror: a mass of corpses in a caved-in trench and, especially, the sight of a woman’s leg sticking out at an unnatural angle which haunted her for decades. She lost her mother and a son in the massacre. But Tran Thi Nhut never set foot in My Lai. She lived two provinces north, in a little hamlet named Phi Phu which—she and other villagers told me—lost more than 30 civilians to a 1967 massacre by U.S. troops.

I remember Pham Thi Luyen who lived several provinces north in Trieu Ai village, Quang Tri Province. Decades old Marine Corps court martial records—which told a story of scared and angry Americans under command of an officer bent on revenge for recent casualties—led me to her hamlet. There, she and other survivors told me what it was like to live through a night of sheer terror, in October 1967, when Americans threw grenades into bomb shelters with women and children inside and gunned down men and women in cold blood. It was the night that Pham Thi Luyen became an orphan and 12 fellow villagers died.

I think of Bui Thi Huong who was, according to court-martial records, gang-raped in Xuan Ngoc hamlet by five Marines while her mother-in-law, sister-in-law, husband, and 3-year-old son were shot dead. Her 5-year-old niece was slain too, but by another method. The Marine who killed her did so by “mashing up and down with his rifle,” according to a fellow unit member. Another recalled, “I said one… two… three… And he was hitting the baby with the [rifle] butt!”

I recall too my conversations with Pham Thi Cuc, Le Thi Chung, and Le Thi Xuan who told me about a 1966 massacre by Americans in My Luoc hamlet that claimed the lives of 16 civilians. I think of Vi Thi Ngoi, an elderly woman who told me about the day American and South Korean troops opened fire on more than 100 of her fellow villagers and of the bodies that fell on her tiny frame, shielding her from the bullets. I remember how she explained what it felt like to lie there, for what seemed like an eternity, feigning death, amid the blood and viscera of friends and neighbors.

I think about young American men who shot down innocents in cold blood and then kept silent for decades. I think about horrified witnesses who lived with the memories.

Survivors recall their memories in 2000 of the mass killing of fellow villagers by U.S. soldiers during the Vietnam War, in My Lai, Vietnam. (Nick Ut/AP)

I remember my time spent talking with Jamie Henry, decades after he had been a young draftee and then a decorated medic. Just over a month before the My Lai massacre, Henry’s unit entered a small hamlet, rounded up the civilians—about 19 women and children—and gathered them together. A lieutenant asked his superior, a West Point-trained captain, what he should do with them. As Henry later told an Army criminal investigator in a sworn statement: “The captain asked him if he remembered the op order [operation order] that had come down from higher [headquarters] that morning which was to kill anything that moves. The captain repeated the order. He said that higher said to kill anything that moves.” Henry tried to intervene, but instead could only watch as fellow unit members opened fire on the civilians. An Army investigation determined the massacre occurred just as Henry said it did, but no action was taken against any of the troops involved, while the files were kept secret and buried away for decades.

In short, on this anniversary, I think of all the My Lais that most Americans never knew existed and few are aware of today. I think about young American men who shot down innocents in cold blood and then kept silent for decades. I think about horrified witnesses who lived with the memories. I think of the small number of brave whistleblowers who stood up for innocent, voiceless victims. But most of all, I think of the dead Vietnamese of all the massacres that few Americans knew about and fewer still cared about.

I think of the victims in Phi Phu and Trieu Ai and My Luoc and so many other tiny hamlets I visited in Vietnam’s countryside. And then I think of all the villages I never visited; the massacres unknown to all but the dwindling number of survivors and their families; the stories we Americans will likely never know.

I wonder if, 45 years hence, someone might be writing a similar op-ed about civilian lives lost these past years in Iraq or Afghanistan, Pakistan or Yemen; about killings kept under wraps and buried in classified files or simply locked away in the hearts and minds of the perpetrators and witnesses and survivors. Four and half decades from now, will we still reserve only this day to focus on these hard truths and hidden histories? Or will we finally have learned the lessons of the My Lai massacre and the many other massacres that so many wish to forget and so many others refuse to remember.

Nick Turse is a journalist, historian, and the author of Kill Anything that Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam. Turse’s work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the San Francisco Chronicle, and The Nation, among other publications. His investigations of U.S. war crimes in Vietnam have gained him a Ridenhour Prize for Reportorial Distinction, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a fellowship at Harvard University’s Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.

Copyright © 2013 Global Research

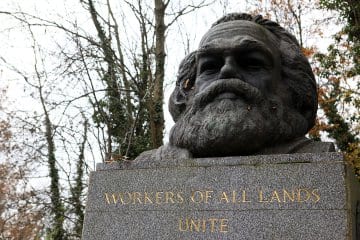

Marx’s Revenge: How Class Struggle Is Shaping the World

Or so we thought. With the global economy in a protracted crisis, and workers around the world burdened by joblessness, debt and stagnant incomes, Marx’s biting critique of capitalism — that the system is inherently unjust and self-destructive — cannot be so easily dismissed. Marx theorized that the capitalist system would inevitably impoverish the masses as the world’s wealth became concentrated in the hands of a greedy few, causing economic crises and heightened conflict between the rich and working classes. “Accumulation of wealth at one pole is at the same time accumulation of misery, agony of toil, slavery, ignorance, brutality, mental degradation, at the opposite pole,” Marx wrote.

A growing dossier of evidence suggests that he may have been right. It is sadly all too easy to find statistics that show the rich are getting richer while the middle class and poor are not. A September study from the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) in Washington noted that the median annual earnings of a full-time, male worker in the U.S. in 2011, at $48,202, were smaller than in 1973. Between 1983 and 2010, 74% of the gains in wealth in the U.S. went to the richest 5%, while the bottom 60% suffered a decline, the EPI calculated. No wonder some have given the 19th century German philosopher a second look. In China, the Marxist country that turned its back on Marx, Yu Rongjun was inspired by world events to pen a musical based on Marx’s classic Das Kapital. “You can find reality matches what is described in the book,” says the playwright.

(MORE: Can China Escape the Middle-Income Trap?)

That’s not to say Marx was entirely correct. His “dictatorship of the proletariat” didn’t quite work out as planned. But the consequence of this widening inequality is just what Marx had predicted: class struggle is back. Workers of the world are growing angrier and demanding their fair share of the global economy. From the floor of the U.S. Congress to the streets of Athens to the assembly lines of southern China, political and economic events are being shaped by escalating tensions between capital and labor to a degree unseen since the communist revolutions of the 20th century. How this struggle plays out will influence the direction of global economic policy, the future of the welfare state, political stability in China, and who governs from Washington to Rome. What would Marx say today? “Some variation of: ‘I told you so,’” says Richard Wolff, a Marxist economist at the New School in New York. “The income gap is producing a level of tension that I have not seen in my lifetime.”

Tensions between economic classes in the U.S. are clearly on the rise. Society has been perceived as split between the “99%” (the regular folk, struggling to get by) and the “1%” (the connected and privileged superrich getting richer every day). In a Pew Research Center poll released last year, two-thirds of the respondents believed the U.S. suffered from “strong” or “very strong” conflict between rich and poor, a significant 19-percentage-point increase from 2009, ranking it as the No. 1 division in society.

The heightened conflict has dominated American politics. The partisan battle over how to fix the nation’s budget deficit has been, to a great degree, a class struggle. Whenever President Barack Obama talks of raising taxes on the wealthiest Americans to close the budget gap, conservatives scream he is launching a “class war” against the affluent. Yet the Republicans are engaged in some class struggle of their own. The GOP’s plan for fiscal health effectively hoists the burden of adjustment onto the middle and poorer economic classes through cuts to social services. Obama based a big part of his re-election campaign on characterizing the Republicans as insensitive to the working classes. GOP nominee Mitt Romney, the President charged, had only a “one-point plan” for the U.S. economy — “to make sure that folks at the top play by a different set of rules.”

Amid the rhetoric, though, there are signs that this new American classism has shifted the debate over the nation’s economic policy. Trickle-down economics, which insists that the success of the 1% will benefit the 99%, has come under heavy scrutiny. David Madland, a director at the Center for American Progress, a Washington-based think tank, believes that the 2012 presidential campaign has brought about a renewed focus on rebuilding the middle class, and a search for a different economic agenda to achieve that goal. “The whole way of thinking about the economy is being turned on its head,” he says. “I sense a fundamental shift taking place.”

(MORE: Viewpoint: Why Capping Bankers’ Pay Is a Bad Idea)

The ferocity of the new class struggle is even more pronounced in France. Last May, as the pain of the financial crisis and budget cuts made the rich-poor divide starker to many ordinary citizens, they voted in the Socialist Party’s François Hollande, who had once proclaimed: “I don’t like the rich.” He has proved true to his word. Key to his victory was a campaign pledge to extract more from the wealthy to maintain France’s welfare state. To avoid the drastic spending cuts other policymakers in Europe have instituted to close yawning budget deficits, Hollande planned to hike the income tax rate to as high as 75%. Though that idea got shot down by the country’s Constitutional Council, Hollande is scheming ways to introduce a similar measure. At the same time, Hollande has tilted government back toward the common man. He reversed an unpopular decision by his predecessor to increase France’s retirement age by lowering it back down to the original 60 for some workers. Many in France want Hollande to go even further. “Hollande’s tax proposal has to be the first step in the government acknowledging capitalism in its current form has become so unfair and dysfunctional it risks imploding without deep reform,” says Charlotte Boulanger, a development official for NGOs.

His tactics, however, are sparking a backlash from the capitalist class. Mao Zedong might have insisted that “political power grows out of the barrel of a gun,” but in a world where das kapital is more and more mobile, the weapons of class struggle have changed. Rather than paying out to Hollande, some of France’s wealthy are moving out — taking badly needed jobs and investment with them. Jean-Émile Rosenblum, founder of online retailer Pixmania.com, is setting up both his life and new venture in the U.S., where he feels the climate is far more hospitable for businessmen. “Increased class conflict is a normal consequence of any economic crisis, but the political exploitation of that has been demagogic and discriminatory,” Rosenblum says. “Rather than relying on (entrepreneurs) to create the companies and jobs we need, France is hounding them away.”

The rich-poor divide is perhaps most volatile in China. Ironically, Obama and the newly installed President of Communist China, Xi Jinping, face the same challenge. Intensifying class struggle is not just a phenomenon of the slow-growth, debt-ridden industrialized world. Even in rapidly expanding emerging markets, tension between rich and poor is becoming a primary concern for policymakers. Contrary to what many disgruntled Americans and Europeans believe, China has not been a workers’ paradise. The “iron rice bowl” — the Mao-era practice of guaranteeing workers jobs for life — faded with Maoism, and during the reform era, workers have had few rights. Even though wage income in China’s cities is growing substantially, the rich-poor gap is extremely wide. Another Pew study revealed that nearly half of the Chinese surveyed consider the rich-poor divide a very big problem, while 8 out of 10 agreed with the proposition that the “rich just get richer while the poor get poorer” in China.

(MORE: Is Asia Heading for a Debt Crisis?)

Resentment is reaching a boiling point in China’s factory towns. “People from the outside see our lives as very bountiful, but the real life in the factory is very different,” says factory worker Peng Ming in the southern industrial enclave of Shenzhen. Facing long hours, rising costs, indifferent managers and often late pay, workers are beginning to sound like true proletariat. “The way the rich get money is through exploiting the workers,” says Guan Guohau, another Shenzhen factory employee. “Communism is what we are looking forward to.” Unless the government takes greater action to improve their welfare, they say, the laborers will become more and more willing to take action themselves. “Workers will organize more,” Peng predicts. “All the workers should be united.”

That may already be happening. Tracking the level of labor unrest in China is difficult, but experts believe it has been on the rise. A new generation of factory workers — better informed than their parents, thanks to the Internet — has become more outspoken in its demands for better wages and working conditions. So far, the government’s response has been mixed. Policymakers have raised minimum wages to boost incomes, toughened up labor laws to give workers more protection, and in some cases, allowed them to strike. But the government still discourages independent worker activism, often with force. Such tactics have left China’s proletariat distrustful of their proletarian dictatorship. “The government thinks more about the companies than us,” says Guan. If Xi doesn’t reform the economy so the ordinary Chinese benefit more from the nation’s growth, he runs the risk of fueling social unrest.

Marx would have predicted just such an outcome. As the proletariat woke to their common class interests, they’d overthrow the unjust capitalist system and replace it with a new, socialist wonderland. Communists “openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions,” Marx wrote. “The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains.” There are signs that the world’s laborers are increasingly impatient with their feeble prospects. Tens of thousands have taken to the streets of cities like Madrid and Athens, protesting stratospheric unemployment and the austerity measures that are making matters even worse.

So far, though, Marx’s revolution has yet to materialize. Workers may have common problems, but they aren’t banding together to resolve them. Union membership in the U.S., for example, has continued to decline through the economic crisis, while the Occupy Wall Street movement fizzled. Protesters, says Jacques Rancière, an expert in Marxism at the University of Paris, aren’t aiming to replace capitalism, as Marx had forecast, but merely to reform it. “We’re not seeing protesting classes call for an overthrow or destruction of socioeconomic systems in place,” he explains. “What class conflict is producing today are calls to fix systems so they become more viable and sustainable for the long run by redistributing the wealth created.”

(MORE: Is It Time to Stop Green-Lighting Red-Light Cameras?)

Despite such calls, however, current economic policy continues to fuel class tensions. In China, senior officials have paid lip service to narrowing the income gap but in practice have dodged the reforms (fighting corruption, liberalizing the finance sector) that could make that happen. Debt-burdened governments in Europe have slashed welfare programs even as joblessness has risen and growth sagged. In most cases, the solution chosen to repair capitalism has been more capitalism. Policymakers in Rome, Madrid and Athens are being pressured by bondholders to dismantle protection for workers and further deregulate domestic markets. Owen Jones, the British author of Chavs: The Demonization of the Working Class, calls this “a class war from above.”

There are few to stand in the way. The emergence of a global labor market has defanged unions throughout the developed world. The political left, dragged rightward since the free-market onslaught of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, has not devised a credible alternative course. “Virtually all progressive or leftist parties contributed at some point to the rise and reach of financial markets, and rolling back of welfare systems in order to prove they were capable of reform,” Rancière notes. “I’d say the prospects of Labor or Socialists parties or governments anywhere significantly reconfiguring — much less turning over — current economic systems to be pretty faint.”

That leaves open a scary possibility: that Marx not only diagnosed capitalism’s flaws but also the outcome of those flaws. If policymakers don’t discover new methods of ensuring fair economic opportunity, the workers of the world may just unite. Marx may yet have his revenge.

— With reporting by Bruce Crumley / Paris; Chengcheng Jiang / Beijing; Shan-shan Wang / Shenzhen

When Chileans Said “No” to Pinochet

Happiness is Skateboarding Over Evil

by SAUL LANDAU

The new film, “No”, takes place in Chile in 1988 as the nation faced a plebiscite — a vote of all citizens –on whether to keep General Augusto Pinochet in power, or not. The Army commander who seized power after a 1973 military coup against elected President Salvador Allende had ruled for more years than Hitler, and had become an old man who gained international notoriety by assassinating, disappearing,” torturing, and sending opponents into exile. But the foreign investors praised his embrace of Chicago Boys economics, a supposedly free market economy whereby proletarios (proletarians) could evolve into proprietarios (property owners), which in practice meant that capitalists could buy Chile’s forests and convert them into chopsticks and tooth picks.

The new film, “No”, takes place in Chile in 1988 as the nation faced a plebiscite — a vote of all citizens –on whether to keep General Augusto Pinochet in power, or not. The Army commander who seized power after a 1973 military coup against elected President Salvador Allende had ruled for more years than Hitler, and had become an old man who gained international notoriety by assassinating, disappearing,” torturing, and sending opponents into exile. But the foreign investors praised his embrace of Chicago Boys economics, a supposedly free market economy whereby proletarios (proletarians) could evolve into proprietarios (property owners), which in practice meant that capitalists could buy Chile’s forests and convert them into chopsticks and tooth picks.

After 15 years of military dictatorship and unbridled capitalism, Chileans got to vote to allow Pinochet to continue his rule. It was “Yes” or “No” — open the political game to a genuine choice. The film focuses on the “No,” campaign waged by the anti-Pinochet forces. To win voters, Chilean TV offered each side a series of 15 minute daily programs.

The old Chilean lefties, who directed the campaign had no experience in selling their side of the story on television; so they choose René Saavedra (Gael Garcia Bernal), a talented ad man, to design the campaign to convince the Chilean majority to reject Pinochet.

Rene designs the commercials in the style he perfected through making soft drink commercials and soap opera promotions, to use the zeal shown by actors pitching a fizzy drink to deliver a message for a new, happier Chile. But Rene must spar with left-wing ideologues about the contents of the message. All recognize the fact that Pinochet had to concede to the referendum because of strong foreign pressure to legitimize a government that was inherently illegitimate—Pinochet’s coup and post-coup brutality was directed against an elected government, and the Chilean population that supported it.

The film also turns into a contest between two Chilean ad men, both adherents of the Madison Avenue alchemy of selling shit by making it smell like perfume.

Rene lives with his eight year-old son (Pascal Montero), both abandoned by his estranged wife Veronica (Antonia Zegers), a miitant leftist who thinks “No” cannot win because Pinochet will rig the results and intimidate the public. But Rene, despite the threat his involvement holds toward his career in advertising, agrees to take on the campaign. His boss at the commercial ad agency, Lucho Guzman (Alfredo Castro), a Pinochetista, colludes with a Cabinet Minister (Jaime Vadell) to direct the “Yes” campaign.

The audience gets a visual education in commercial production, but this does not substitute for character building and inter-personal stories, the lack of which weakens the movie. The film also gets lost in the commercials and loses the important political context that has generated the story.

We do, however, see convincing scenes of Pinochet’s forces attacking peaceful crowds, using violence as their primary means of persuasion. Rene at one point must fear for his son’s safety, as the “Yes” advisors become anxious when they see that the “No” is gaining popularity in the polls, and begin to threaten people working for the “No.”.

The inner plot, Rene’s attempt to win back his estranged wife, becomes a welcome relief from the drumming of the ad campaign. His wife still likes Rene, but whatever made them separate remains fixed strongly in her mind—unfortunately, we never find out what it is. As she rejects his overtures to have sex and reunite, the film makes no attempt to illuminate the barriers to resolving their relationship.

The anti-Pinochet Chileans behind the “No” commercials get irritated by Rene’s peddling their political voice like a commodity. They insist their 15-minute nightly TV allocation should portray Pinochet’s brutality, show his goons doing their violence and lawlessness, exposing the crimes of the regime. Rene, the ad man, calculates that selling “No” instead requires commercial TV advertising techniques. He doesn’t belong in the world of ideas, but in the psychological domain of manipulating complacent and frightened buyers to accept his product. In this way, the movie participates in the trivialization of actual mass mobilizations, door-to-door campaigning, and the vast amounts of literature that anti-Pinochet forces produced for this effort.

Some Chileans, despite their disgust over what Pinochet had done to their people and country, feared his ouster would bring economic chaos, unemployment, massive poverty. Rene thinks about how these factors might reduce voter turnout. He answers these perturbing issues by peddling happiness. His nightly TV spots emphasize the promise of future contentment if No wins. He attaches a rainbow backdrop to the entire ad campaign. Beautiful outdoor scenes feature gleeful dancers and jubilant children, all with their feet moving rhythmically. Oh joy!

As the historic day of the vote approaches, the film centers on the competition between the Yes and No ads, a back-dated Mad Men scenario that overstresses the making of the commercials as the center of history.

A welcome and nicely underplayed strain of humor, however, accompanies the use of contrived marketing tricks and simplistic messages to bring down a dictatorship. The film shows how silly jingles and staged cheerfulness became useful political tools.

That ad man element gets enhanced when the Yes side, aided by Guzman, modifies its campaign accordingly. The film also ends on a note of droll realism. Rene skate boards along the streets, as if to demonstrate that despite his marital woes the boy part of him remains alive and well, and to celebrate the victory of good — happiness is skateboarding – over evil.

Bernal acknowledges his victory with quiet intensity and skeptical facial expressions. He, and the film’s director Pablo Larrain, hint that the superficiality of Rene’s advertising schemes will endure beyond the No vote, and etch themselves deeply in Chile’s destiny. Indeed, the newly democratic Chile remained a country where consumerism prevailed, a place divided by class, wealth and power— and the succeeding governments would behave in the world of commodity production and mass consumption where desire produced by advertising acted as a control on social behavior.

Saul Landau is filming (with Jon Alpert) a documentary on Cuba’s anti homophobia campaign. His “Fidel” and “Will The Real Terroris Please stand Up” are available on dvd from cinemalibrestudio.com