Art, war and social revolution—Part 2

![]()

Films and TV put in their cultural and political contexts.

Films and TV put in their cultural and political contexts.

A talk given in San Diego, Berkeley and Ann Arbor

By David Walsh, wsws.org

1 June 2016

The various writers may step back occasionally to reflect on individual moral issues, or the debilitating impact of the war on their respective central characters, but never to consider the driving forces of the war itself. Not once. No one makes a genuinely profound critique of the society that produces these horrible wars, or ties them to capitalism.

The Cold War: “You can’t fight in here. This is the war room!”

Dr. Strangelove (1964)

The Cold War produced many works, including a great deal of reactionary rubbish. But there were certain films that stood out. Stanley Kubrick directed Paths of Glory (1957), as noted before, a scathing indictment of the First World War. Kirk Douglas plays a French officer whose men refuse to continue a suicidal attack. They then face a court-martial. It is a powerful and disturbing film.

Kubrick, of course, also made Dr. Strangelove (1964), a satire about a lunatic US Air Force general who launches a first nuclear strike against the Soviet Union. Peter Sellers memorably plays three parts, including US president Merkin Muffley and the ex-Nazi, wheelchair-bound Dr. Strangelove. The film is an absurdist reaction to the terrors of the time. Who can forget President Muffley chastising the Soviet ambassador and another US air force general for wrestling in the American military’s sanctum sanctorum: “You can’t fight in here. This is the war room!” A sort of nervous hysteria prevails.

Other films of the time included Stanley Kramer’s On the Beach (1959), based on Nevil Shute’s novel, about a group of people in Australia, in the aftermath of World War III, who are waiting for the cloud of deadly nuclear fallout to arrive and exterminate them; John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate (1962), a delirious, bewildering film about the brainwashing of the son of a right-wing politician unwittingly enlisted in a “communist conspiracy,” with Angela Lansbury as a monstrous political mother-wife; Frankenheimer’s Seven Days in May (1964), with Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas, about an attempted military coup; Sidney Lumet’s Fail Safe (1964), from a screenplay co-written by former blacklisted writer Walter Bernstein, about a Cold War nuclear crisis.

I would not go out too far on the limb artistically with any of these films. But they reflected tremendous anxiety about the global (or specifically American) state of affairs, and they tackled the questions directly, or at least as directly as the circumstances allowed.

Vietnam

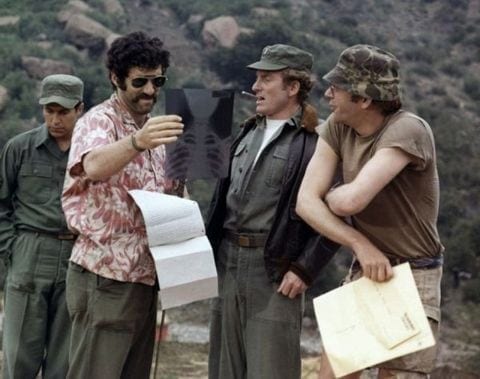

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]ith the Vietnam War, all hell broke loose, so to speak. Generally speaking, the Vietnam-era films are critical of the war, of the military, of the establishment. Of course, they also reflect the contradictions and limitations of the radicalism of the period. Robert Altman’s MASH (1970), set during the Korean War, in fact, but obviously directed at the Vietnam War, the American military and the Nixon administration, established the tone. The film was written by Ring Lardner Jr., another former Hollywood blacklist victim.

One could point to Hal Ashby’s Coming Home (1978), Sidney J. Furie’s The Boys in Company C (1978), Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978), Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), Oliver Stone’s Platoon and Born on the Fourth of July (1986), Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1987), Brian de Palma’s Casualties of War (1989) and others.

Those films are overwhelmingly negative about the war, about the military. They come out of, in a number of cases, the anti-war movement. These are honest, often confused films, none of them great works of art, but with some extraordinary moments. They exude the spirit of rebellion. Those who take military rules and pronouncements seriously are deluded or mad …

In discussing these various war films, we are not looking back nostalgically to some golden age—there never was a golden age. America is a very dark country in many ways, the major imperialist power of the past century.

How do we look at films?

How do we look at these films, how do we look at present-day films? This raises the question: What is art? What is our approach in evaluating art?

For Marxists, art is ultimately a means by which we cognize, make sense of reality, it is no less concerned with truth than the objective sciences, although in a different way obviously.

We criticize or reject didacticism, preaching in art, because in a didactic work the artist has a prosaic, cut and dried content and the artistic shape is merely an ornament, something extraneous. Such work does not make a deep or enduring impression; it lacks spontaneity, life.

Art largely shows, it doesn’t explain—except in unusual cases. Filmmakers think in images, they dramatize their conceptions. The conceptions are embodied in the relationships, situations and imagery.

This doesn’t mean, of course, that the artist has no opinions or ideas. He or she works through images, feelings play an important role, but feelings attached to thought. The artist doesn’t assume that the audience is a quivering mass of emotionalism to be manipulated.

The best films I’ve mentioned tended to look at American society critically, with the military viewed as one component of the social order. There was a greater awareness of the society’s faults, weaknesses. A more pronounced realism predominated.

And it isn’t simply a matter of the explicitly political level of consciousness. One watches The Best Years of Our Lives, From Here to Eternity, They Were Expendable and others, or read the Jones and Mailer novels, and they are not necessarily works of genius, but they give a sense of the American people, or at least in certain important aspects. There is a much closer relationship in those films and novels to everyday life, especially the distrust of the military brass, of big shots in general.

In one of the opening scenes of The Best Years of Our Lives, one of those big shots basically elbows the Dana Andrews character out of the way at an airline counter. (Self-importantly: “I arranged to have my tickets here. My name is Gibbons. George H Gibbons.”) The class issues are laid out at the very outset.

The enormous distance of filmmaking today, commercial or independent, from the people, the way it actually thinks and feels, is so striking, and I’m speaking, frankly, even of those films and television series that make a special effort to present “ordinary people.”

The connection to the people was much more organic, despite the social, profit-driven character of Hollywood. It was taken for granted that the rich were less interesting, selfish, lazy, self-involved, that the big dramas lay in the working class neighborhoods or workplaces, or in the more intriguing sections of the middle class, whether past or present—or in the drama of science, or war, or political struggles of the past.

Of course, there were the performers themselves, the human material. They didn’t have to pretend so hard to be “average,” they came out of the hardships of the Depression and the war, and they represented something.

The anti-communist purges, the changes in American economic life, the immense social polarization of recent decades, the decades of ideological reaction, all this has had a great impact. Revitalized filmmaking will come out of a new period of struggles, out of defeats and hard-fought lessons, out of painful and exhilarating experiences.

Where is the work that has captured the horror of the “war on terror”?

Now, we’ve had 25 years of war … by now, you would think a great work would have appeared.

Where is the film or novel (or drama or poem or painting) that has captured for an entire generation the horror of the “war on terror”? This is a central issue in this talk, a central problem …

The McCarthy period in the early 1950s was a time of intense repression, but, in many respects, better film work was being done. The problem is not just repression, or even primarily repression. American capitalism’s most powerful weapon is not repression, but the threat of ostracism, the power of conformism. And this itself is largely a product of the absence of a political, social alternative, a mass-based, anti-capitalist opposition. So that all the countervailing forces act on the filmmakers. Their powers of resistance are weakened.

No one has been able to capture the past quarter-century because none of the artists understand the times through which they themselves have lived or are oriented to that sort of broad historical and social representation. It’s a problem and I’ll return to it.

I want to say a few words about what has been produced in recent decades.

Studies of post-September 2001 cinema, for example, are obliged to confront such tendencies as “porno-sadism” and “torture porn,” in the form of films consumed by unrestrained indulgence in bloody revenge fantasies. Entire franchises have been built out of inflicting pain and terror.

Of course, all this did not begin on September 11. The decay and decline of American bourgeois society and its culture has been a protracted process. The mid- to late 1970s witnessed a proliferation of “vigilante” films (Death Wish, et al.), which already signified a diseased mood emerging in sections of the affluent middle class. Moreover, the “action hero” who took on an army of terrorists or criminals, who somehow single-handedly—and fantastically—overcame America’s decline on the world stage was a film phenomenon that grew more and more prominent in the 1980s and 1990s.

But the terrorist attacks of September 11 gave a license, a legitimacy to the public expression of genuinely depraved sentiments that had been long accumulating.

In “A Culture at the End of its Rope,” written in June 2004, in response to Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill, Vol. 2, we made some points that I think still stand up:

This is a film whose subject matter is torturing and murdering and bloody revenge. It has the word “Kill,” as an imperative [a command], in its title. Remove the pointless dialogue, the self-conscious references to countless other films, the various camera and editing gimmicks, the heaps of self-satisfaction and self-aggrandizement, and what remains? A work about a group of psychopaths eliminating one another. The first speech of the film contains the word “sadism.” …

We will be told by some that Tarantino is merely reflecting the violence in the society around him, or even that he is holding it up to criticism. Nonsense. Kill Bill is not a critique of sadistic bullying, it revels in it. A calculated, manipulative (and orgasmic) heaping up of violent acts cannot possibly constitute a rejection or a critique.

It is not necessary to repeat or extend these comments in regard to every example of violence, sadism and cruelty in American popular culture over the past two decades, in film, television, music, video games and so forth.

K. Sutherland played the hero in the despicable Fox hit series “24” glorifying the Deep State’s pseudo war against a terrorism that it cynically created. Do actors EVER exercise their brains or are they just moronic narcissists?

But one more example: Fox Television’s “24” which first went on the air in November 2001, created by right-wing Bush supporters, pioneered the favorable representation of torture.

Brian Finney, in Terrorized: How the War on Terror Affected American Culture and Society, writes “The Parents Television Council calculated that 24 showed 67 scenes of torture during its first five seasons, about one incident of torture every other episode, or 12 times a day in fictional time.

“Torture became at least an intermittent feature on such shows as The Unit, Lost, JAG, Alias, and Battlestar Galactica, and in numerous hit movies such as The Passion of the Christ, Casino Royale, and The Dark Knight … The Parents Television Council researched the number of scenes of torture shown on prime time television. Between 1995 and 2001 there were 110 scenes, an average of 16 a year. Between 2002 and 2005 the number increased to 624, an average of 156 scenes a year, and between 2006 and 2007 there were 212 scenes, averaging 106 a year.” (Brian Finney).

We have written extensively about such despicable works as Zero Dark Thirty, the purported story of the decade-long search for Osama bin Laden. Not only did Kathryn Bigelow and Mark Boal create a new film sub-genre, the “art torture film,” they did it, as journalist Seymour Hersh has revealed, on the basis of a pack of lies.

Films and novels on the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan

Dozens of films have been made about 9/11 or have been inspired by the subsequent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, ranging from the openly reactionary and bloodthirsty to the more thoughtful and critical.

These are a few of the films treating the “war on terror,” the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan:

Jarhead (2005), Syriana (2005), The Situation (2005), Home of the Brave(2006), Death of a President (2006), United 93 (2006) Battle for Haditha(2007), Grace is Gone (2007), Charlie Wilson’s War (2007), In the Valley of Elah (2007), Lions for Lambs (2007), Redacted (2007), Rendition (2007), Stop-Loss (2008), W. (2008), War, Inc. (2008), Body of Lies (2008), Traitor (2008), The Hurt Locker (2009), Brothers (2009), Green Zone (2010), American Sniper(2014). One could add numerous others that obviously reference 9/11 (War of the Worlds, 2005) or the invasion of Iraq, including James Cameron’s Avatar(2009).

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]here are numerous pointed works here (Syriana, In the Valley of Elah, Redacted, Rendition, The Situation, Death of a President and Battle for Haditha), as well as some truly lamentable ones or worse (Charlie Wilson’s War, Lions for Lambs, Traitor, The Hurt Locker and American Sniper).

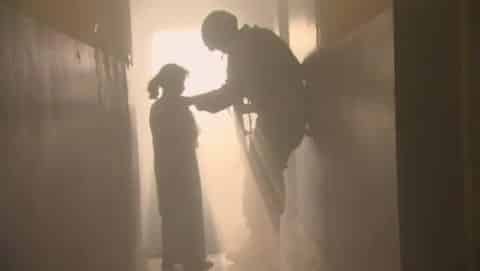

In my view, British director Nick Broomfield’s Battle for Haditha—about a massacre carried out by US marines in November 2005—is the strongest of the lot, for its treatment of both the Iraqi civilians and US troops as victims of imperialist war. The final dreamlike sequence, in which an American marine takes the hand of a small Iraqi girl who survived the attack, is deeply moving.

Redacted, directed by Brian De Palma, recounts in fictional form the rape and murders carried out by US soldiers in March 2006 in Mahmudiyah, Iraq. One author writes, “ Redacted concludes with a series of real-life still photographs of dead Iraqis in a sequence called ‘Collateral Damage,’ images that were denied to the American public in the drive to mythologise the war and the reasons why it was being fought.” (Terence McSweeney, The ‘War on Terror’ and American Film: 9/11 Frames Per Second)

As we noted in 2010, there are numerous “pointed films … but if one may say it, these are primarily ‘small-bore’ works, works that take up elements, specific aspects of the situation. If one compares them, as a body, with Apocalypse Now, or even Platoon, for all its histrionics—the latter were movies that attempted to make a broad statement about American involvement in Vietnam, to paint it as a crime, as an imperialist crime. This element is largely missing today.”

Dozens and dozens of novels have appeared that treat the “war on terror” or the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, some of them written by veterans of those conflicts.

Ian McEwan’s Saturday (2005) and John Updike’s Terrorist (2006), both shallow and contrived novels, essentially adopt the establishment point of view.

Lea Carpenter’s Eleven Days (2013) is a deplorable work. It celebrates the efforts of US Special Operations Forces, America’s death squads. Carpenter is a descendant of the original du Pont in America. Her father served in US Army Intelligence in China and Burma. She was previously the deputy publisher of the Paris Review, the literary magazine. She is married to the former managing director of Goldman Sachs, specializing in mergers and acquisitions.

In her novel, the hero, a member of the Special Operations Forces, thinks to himself, after an intervention against Al Qaeda: “Did these contemporary war stories lack the grandeur and arc of their predecessors? Sadr City was not the Somme. That was like comparing Mad Max to Madame Bovary. But they were alike in this simple fact: men were killing other men across a small space to save the lives of millions of others half a world away. Historians would eventually take their pick of the facts and look at the larger questions, but the first wave of understanding would come from the guys who were there.”

Saving the world for Goldman Sachs. This is what passes for the American intelligentsia.

Redeployment, a collection of stories about the Iraq war, by Phil Klay, is one of the best known books written by an Iraqi war veteran. Klay enlisted in the Marines and served as a Public Affairs Officer in the surge in Iraq in 2008.

In “After Action Report,” one of the newer members of the narrator’s unit shoots an Iraqi teenager who apparently has grabbed an AK-47. This soldier, “like the rest of us, had actually been trained to fire a rifle, and he’d been trained on man-shaped targets. Only difference between those and the kid’s silhouette would have been the kid was smaller. Instinct took over. He shot the kid three times before he hit the ground. Can’t miss at that range. The kid’s mother ran out to try to pull her son back into the house. She came just in time to see bits of him blow out of his shoulders.”

Kevin Powers, the author of The Yellow Birds, also served in Iraq, as a machine gunner in Mosul and Tal Afar. His novel centers on the efforts of its narrator—a US soldier in Iraq—to prevent the death of a younger, fellow private, an effort that fails. The book expresses considerable disgust and anger. At one point, the narrator is considering suicide:

Or should I have said that I wanted to die, not in the sense of wanting to throw myself off of that train bridge over there, but more like wanting to be asleep forever because there isn’t any making up for killing women or even watching women get killed, or for that matter killing men and shooting them in the back and shooting them more times than necessary to actually kill them and it was like just trying to kill everything you saw sometimes because it felt like there was acid seeping down into your soul and then your soul is gone and knowing from being taught your whole life that there is no making up for what you are doing …

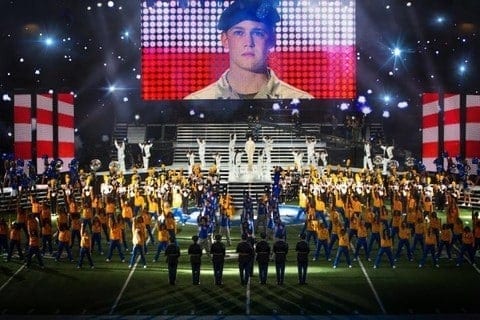

Ben Fountain’s Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, is essentially a satirical work. The novel, a film version of which is coming out directed by Ang Lee, is not so much a novel about Iraq (Fountain is not a veteran) as it is a sharp look at phony patriotism, hypocritical religiosity and corporate greed in Bush’s Texas. The sentiments are legitimate enough, but the targets are fairly easy ones at this point in history. In the end, despite its decent intentions, the book is a little too light-hearted and “soft.”

One comes across in Fountain’s novel to the only reference in any of the novels to a possible ulterior motive on the part of the US authorities. The central character, Billy Lynn, is home and talking to his sister. She says: “Then let me ask you this, do you guys believe in the war? Like is it good, legit, are we doing the right thing? Or is it all really just about the oil?” Billy replies, “You know I don’t know that,” and, later, “I don’t think anybody knows what we’re doing over there.” That’s it, the only discussion of what the US is doing in Iraq or Afghanistan.

Disparate as they are, these latter novels or stories share certain features. None of them discuss the history of the region or the broader motives for American military intervention. Each prides itself on immediacy and immersing the reader in that immediacy. The various writers may step back occasionally to reflect on individual moral issues, or the debilitating impact of the war on their respective central characters, but never to consider the driving forces of the war itself. Not once. No one makes a genuinely profound critique of the society that produces these horrible wars, or ties them to capitalism.

Is it possible to do artistic justice to events as complex and momentous as the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan when one has little or no grasp of their broader significance? Such an approach has an influence on the way in which a given writer treats human psychology and the relationships between people.

The conceptions on the whole are limited. The language tends to be flat, “even-handed,” largely non-committal, matching the writers’ attitude to the war itself.

These novels and stories are efforts at realism, but they evade one of the greatest challenges a fiction writer faces, that of providing historical realism, a general picture of a society and its contradictory parts and an overall sense of the character of the times. In the almost complete absence of that, the movement of individuals inevitably has a flattened, reduced quality. People move about, but only for the most immediate reasons. What is driving them in a more profound sense?

No one is taking on the problems head-on, no one has artistically captured the last quarter century.

Where do some of the difficulties come from?

Where do some of the current artistic difficulties come from?

The unpreparedness of the artists is a matter of concern for our movement. The artistic representation of life is vital to the education of the working class, and this education is our central task.

The anti-communist purges, the decades of political reaction, the increasing indifference of large sections of the upper-middle class to the conditions of the mass of the population—all these have had their impact.

There are many issues, including occupational hazards, so to speak. Art lags behind events at the best of times. But there is a big problem today with the conception of art itself.

I want to refer in particular to the predominance of postmodernism in recent decades, in various forms. A portion of my generation became cynical, complacent or pessimistic, or all three, and eventually regretted missing out on the big money on Wall Street and elsewhere. While these individuals were protesting in the 1960s and 1970s, others were already getting rich. They later turned against everything they had once believed in and adopted everything they opposed.

The postmodernists declared the end of “grand narratives” or “master narratives.” What this really meant was the end to a search for fundamental causes; instead they refer to countless factors, none of them given precedence. There is no underlying truth to be discovered, simply one’s impressions, one’s narrative. This has played a disastrous role, associated as it is with the abandonment of any sense of revolutionary alternative and with accommodation, concealed behind obscurantist language, to the status quo.

By grand or master narratives the postmodernists had in mind, above all, Marxism and its “narrative” of the class struggle. Coherent theories of historical development, which often involve social emancipation, were outlawed. These grand narratives were to replaced, as one commentator puts it, by “mini-narratives” or “stories that explain small practices, local events, rather than large scale universal or global concepts. Mini-narratives are always situational, provisional, contingent, temporary and make no claim to universality, truth, reason or stability.”

The influences here are Nietzsche, Heidegger and other irrationalist thinkers. This represents not only an attack on Marxism, but on the Enlightenment and the ability to cognize the world in a rational, objective fashion. One is left with fragments and the celebration of fragments.

The art and film of the past several decades has been littered with a multiplicity of “little narratives.” In the case of the artistic treatment of the ongoing wars and the drive to war, this “littleness” jibes all too neatly with the filmmakers’ and novelists’ political and historical reticence, their essential intellectual submission to the official account of the “war on terror” and America’s “humanitarian interventions.”

More than that, the “littleness” justifies and sustains a concern with oneself. The recourse to “mini-narratives” and “small practices” is almost inevitably bound up with the adoption of identity politics, the obsession with one’s race, gender and sexual orientation. The world is incomprehensible, overwhelming, unchangeable, all I know and can know is my immediate, “local” piece of it, my particular narrative. In short, myself. This sort of outlook inevitably encourages selfishness and self-involvement, tedious individualism, which are other characteristics of recent art and film.

Conclusion

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he great novelist Leo Tolstoy—Leon Trotsky pointed out in an obituary—had contributed to the 1905 Revolution in Russia although he was no revolutionary. “Everything that Tolstoy stated publicly” about the cruelty, irrationality and dishonesty of tsarist Russia “in thousands of ways … seeped into the minds of the laboring masses … And the word became deed.”

This is our conception too, that art has the ability to alter the thinking and feeling of masses of human beings. To have that sort of influence, however, the artist must know something important about the world, about society and history. To do something one must be something, as Goethe observed.

Art brings into play the subjective impressions and imagination of the artist. But these impressions and this imagination carry weight and endure, in the end, only in so far as they correspond—in accordance with art’s distinctive mirrors—to life and reality as they are.

We are not dictating this state of affairs—but it is a fact that only the art with something to say about the decisive questions facing masses of people, however indirectly or poetically, will be of great interest in the years to come. Self-absorption and social indifference will be looked on with as much astonishment as contempt.

Clearly, we have entered a new stage of development. The economic and social crisis, along with relentless wars and militarist violence, are fueling the discontent of masses of people and blowing up—or threatening to blow up—political arrangements and set-ups around the globe, including in the US.

We know Bernie Sanders and his type. There is nothing of socialism here. He is proposing mild reforms that portions of the ruling elite itself favor. He supports the ongoing wars with certain criticisms, he approves of the drone strikes. He is an advocate of economic nationalism, lining up the working class here with the American ruling elite against China and other rivals of US imperialism. The essence of socialism is internationalism, the international unity of the working class.

But the Sanders campaign and the response it has evoked are objectively significant. It has scandalized the media and the political establishment, it has disrupted the dominant narrative. In a country supposedly dominated by anti-socialism, anti-communism, someone who advertises himself as a socialist is suddenly the most popular politician in America, and among the young, by a wide margin.

The two-party system in the US has been fatally undermined because it is no longer possible to contain the vast, unbearable social contradictions within that structure. Millions have already drawn conclusions about the present system. The task of our party is to transform an unconscious historical process into a conscious revolutionary movement. The Socialist Equality Party is running candidates, Jerry White and Niles Niemuth, for president and vice president, for that reason.

When we discuss the difficulties of the recent decades, it’s not a matter of painting a gloomy picture. To a certain extent, an inevitable clearing of the decks has taken place. Tendencies that pretended to be socialist or left-wing have been revealed for what they are. Organizations that claim to represent the working class have been exposed in the eyes of millions. The same goes for many cultural figures and trends.

These decades of cultural backwardness have also created the conditions for their opposite, for an “epidemic” within the broader population and culture of humanity, compassion and social criticism. We are witnessing an immense movement to the left. We have no illusions about the confusion that exists, but it should also be clear that the course millions have set out on leads inevitably to revolutionary struggles. The elementary needs and interests of masses of human beings will bring them into a life-and-death confrontation with the ruling class.

The social and economic crisis will not be resolved quickly or easily. There will be opportunity for art to reflect on and reveal the truth about the immensely complex, sometimes confusing and enormously intense experiences that vast numbers of people will pass through.

Our concern, again, is with the political and cultural development of the working class. We need a new art committed to telling the truth at all costs. This new art will be incompatible “with pessimism, with skepticism, and with all the other forms of spiritual collapse” (Trotsky) and will have an unlimited, creative belief in humanity and its future. That’s what we’re dedicated to in the Socialist Equality Party and on the World Socialist Web Site. We encourage you to join that effort.

Concluded

Dave Walsh serves as critic for wsws.org. For our money, he's just about the finest film critic in North America. His use of Marxian analysis makes his analyses especially timely and insightful.

Dave Walsh serves as critic for wsws.org. For our money, he's just about the finest film critic in North America. His use of Marxian analysis makes his analyses especially timely and insightful. Note to Commenters

Due to severe hacking attacks in the recent past that brought our site down for up to 11 days with considerable loss of circulation, we exercise extreme caution in the comments we publish, as the comment box has been one of the main arteries to inject malicious code. Because of that comments may not appear immediately, but rest assured that if you are a legitimate commenter your opinion will be published within 24 hours. If your comment fails to appear, and you wish to reach us directly, send us a mail at: editor@greanvillepost.com

We apologize for this inconvenience.

=SUBSCRIBE TODAY! NOTHING TO LOSE, EVERYTHING TO GAIN.=

free • safe • invaluable

[email-subscribers namefield=”YES” desc=”” group=”Public”]

Nauseated by the

vile corporate media?

Had enough of their lies, escapism,

omissions and relentless manipulation?

Send a donation to

The Greanville Post–or

But be sure to support YOUR media.

If you don’t, who will?