This past May 18th marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of the death Elisha Cook, Jr. at the age of 91. In the two-and-a-half months, I’ve been revisiting some of Cook’s films. Here’s my 1995 obituary as a tribute of renewed admiration for his achievement.

In the opening scene of Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby of 1968, an old apartment manager named Mr. Niklas shows a young couple through the building which is, unbeknownst to them, home to a coven of witches. As they walk through the foyer, Mr. Niklas discovers that the husband is an actor and asks, “Have I seen you in anything?” It’s a sly bit piece of casting that this line should be uttered by one of the great character actors of moving pictures—Elisha Cook, Jr. As in the unsettling amalgam of manic intensity and slightly askew trustworthiness he delivered in Rosemary’s Baby, Cook gave his characters a ruffled quirkiness that made many of them immortal.

Elisha Cook was officially married three times, the first time to singer Mary Gertrude (née Dunckley) Cook (1910-1944) from 1928 until their divorce on November 4, 1941.[10] He then married Illinois native Elvira Ann (Peggy) McKenna in 1943. The couple were married for 25 years until they formally divorced in Inyo County, California, in February 1968. Peggy and Elisha, however, remarried almost four years later on December 30, 1971.[11][9] Their second marriage lasted another 19 years until Peggy's death on December 23, 1990. Various references about Cook state that he had no children from his marriages; yet, his army enlistment record of 1942 documents his marital status as "Divorced, with dependents," which suggests he may have had a child or children with his first wife.[5] He resided for many years in Bishop, California, but he typically spent his summers at Lake Sabrina in the Sierra Nevada.[2] . “When he was wanted in Hollywood,” wrote John Huston, “they sent word up to his cabin by courier. He would come down to do a picture and then withdraw again to his retreat.”

Want him they did. In a career that spanned six decades he appeared in over 100 films.

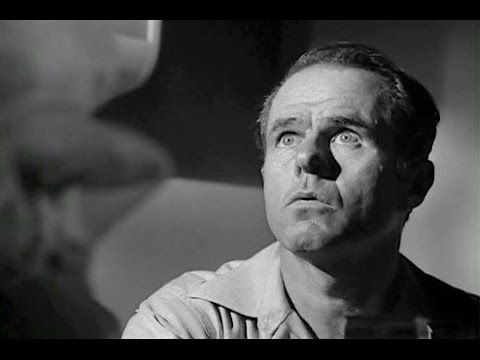

Cook as Wilmer, in the Maltese Falcon (1941).

Huston directed Cook in the 1941 film Maltese Falcon, where he gave his most famous performance— and his own personal favorite —as the gunsel Wilmer, a skittery foil for Humphrey Bogart’s unflappable Sam Spade. Throughout the film Spade taunts Wilmer, impotent in these confrontations even though he is capable of killing. We know it’s just empty talk when Wilmer arches his brow, sticks out his chin and warns Spade, “Keep on ridin’ me, they’re gonna be pickin’ iron out of your liver.” Even facing Wilmer’s pistols, Spade ridicules him and convinces this lethal errand boy’s boss, the Fatman, that his flunky must take the fall. Tears welling in his eyes, Wilmer pleads for permission to kill Spade, but the Fatman must have the falcon: “sorry to lose you, Wilmer, you’re like a son to me.” Spade punches Wilmer and drops him to the floor. Cook had a genius for playing characters who could be bated, manipulated, and done away with.

When Cook decided to leave Broadway for Hollywood (or Hollywoodland as it was then known) in the early 1930’s, the playwright, Owen Davis advised him to be careful about fame: “Junior, if you want to be intelligent, play small parts, because then they can never blame you if the movie is bad.” As in many of his films Cook was not even listed in the opening credits of The Maltese Falcon.

Cook was a small man (5'.5") with a boyish face which he molded brilliantly to expressions of disbelief and indignation. When he appeared in The Maltese Falcon he was nearly forty, but played a kid of about twenty. It is often difficult to gauge someone’s size on the movie screen, and many are the cinematic tricks that inflate the stature of little leading men who must be big. In Howard Hawks’ 1946 The Big Sleep, a film in which Cook and Bogie once again met up, the barrier protecting the hero from his real-life stature is breached with brilliance. In the opening scene of the film a young woman in very short shorts informs detective Philip Marlowe (Bogart),”You’re not very tall are you?” He responds, “I tried to be.” Later in the same film a stool pigeon named Harry Jones (Elisha Cook) offers some information to Marlowe. Jones also lets on that he is going to marrying a woman Marlowe has had a run in with earlier. “She a nice girl,” says Jones. “We’re talking of getting married.” Undoubtedly remembering the jibes about his own height, Marlowe taunts the diminutive thug, “She’s a little big for you. She’ll roll on you and smother you.” Cook activates his talented eyebrows and recoils, wounded: “That’s a dirty crack, brother,” and Marlowe admits it. A short while later Jones is forced to drink poison at gunpoint. When Marlowe discovers Jones’s dead body and calls the police, he describes the victim as a “Little guy. Weighs about 115 pounds.” The dialogue (Williams Faulkner co-wrote the script) is sharp, cutting, but we didn’t need to be told again that the dead man was small. Cook was often cocking his head, looking up at those who would later undo him.

Cuckolded cashier Cook and wifey Marie Windsor, in Kubrick's classic noir The Killing, among their finest performances.

Even the screen’s women towered over him. In Stanley Kubrick’s 1956 film The Killing, Cook gave one of his largest and finest performances as the racetrack cashier George Peatty, the inside man in a complex caper masterminded by a laconic ringleader (Sterling Hayden). When Peatty’s wife Sherry (Marie Windsor) suspects that he may be planning a heist, she plays on his insecurities, and gets him to tell her about the robbery. Sherry’s lover and his gang surprise George in his apartment. George has resorted to crime only to do right by his wife and that naïve love is what brings on the destruction of him and his band of crooks. Cook was great at dying. His Peatty goes out still incredulous that his own wife had betrayed him. Only Cook could have made George Peatty one of the most pathetic characters in all of film noir.

In another of his most memorable roles, Cook played the drummer Cliff Millburn in Phantom Lady (1944). A woman (Ella Raines) is trying to clear her fiancé of murder charges by finding the real killer. Pursuing a lead, she puts on a provocative outfit and goes to a seedy basement jazz club where Cliff, a possible witness, performs an orgasmic drum solo while leering at her, the film intercutting between his overheated rhythmic ejaculations and her self-display. Cook’s antic drumming—however unrealistic—makes for fevered and nightmarish evocation of twisted jazz eroticism.

Elisha as pugnacious sodbuster Torrey about to be blown away by Jack Palance's hired gunman, Jack Wilson, in Shane.

In Shane (1953) Cook was the blustery southerner Stonewall Torrey, a character on the side of righteousness—a rarity among Cook’s roles. The inverse of Wilmer, Torrey is an impotent gunman whose stubbornness gets him killed. Cook recalled a vignette that, at least in my mind, helps the slightest bit to rehabilitate this most sanctimonious of Westerns. Black-hatted Jack Wilson (Jack Palance) goads Torrey into drawing his revolver to defend the honor of his namesake Stonewall Jackson (and Robert E. Lee), whom Wilson has called “trash.” (Author’s note from 2020: Oh, how those Confederate names ring out differently these days!) Torrey barely gets his revolver out of its holster, the barrel angled impotently down in front of him into the mud he’ll soon fall into. Quicker on the draw, Wilson’s gun is pointed right at Torrey, whose height is diminished still further because he’s down in muddy street below the bad guy up on the wooden sidewalk of the Western town. The pair hold their poses for a couple of grueling seconds. Then Wilson guns down the Southerner. As Cook lay in the mud after the scene had been filmed, the director George Stevens ran over to him and yelled “You dumb son of a bitch! See what happens when you stand up for a principle?”

Elijah Cook in The Phantom Lady.

A week ago my wife and I went to a screening of One-Eyed Jacks (1961) starring Marlon Brando, and the only film he ever directed. Near the end of the movie, two men ride into Monterey to rob a bank. When we saw that Elisha Cook was the teller we nudged each other and watched him convert a clichéd scene into a small gem.

Two days later we learned that Elisha Cook had died at the age of 91. The New York Times obituary reported that Cook left no survivors, a statement true only if you think that the family of fabulously dysfunctional characters he created has died with him.

BONUS

Clip from a French interview with Elisha. The man could see and appreciate talent in directors.

ALL CAPTIONS BY THE EDITORS NOT THE AUTHORS.

ANNOTATED BY PATRICE GREANVILLE.

This first appeared in the Anderson Valley Advertiser, May 24, 1995.

The crowning triumph of a career cut tragically short, the final film from Larisa Shepitko won the Golden Bear at the 1977 Berlin Film Festival and went on to be hailed as one of the finest works of late Soviet cinema. In the darkest days of World War II, two partisans set out for supplies to sustain their beleaguered outfit, braving the blizzard-swept landscape of Nazi-occupied Belorussia. When they fall into the hands of German forces and come face-to-face with death, each must choose between martyrdom and betrayal, in a spiritual ordeal that lifts the film’s earthy drama to the plane of religious allegory. With stark, visceral cinematography that pits blinding white snow against pitch-black despair, The Ascent finds poetry and transcendence in the harrowing trials of war. (From Criterion collection edition).

The crowning triumph of a career cut tragically short, the final film from Larisa Shepitko won the Golden Bear at the 1977 Berlin Film Festival and went on to be hailed as one of the finest works of late Soviet cinema. In the darkest days of World War II, two partisans set out for supplies to sustain their beleaguered outfit, braving the blizzard-swept landscape of Nazi-occupied Belorussia. When they fall into the hands of German forces and come face-to-face with death, each must choose between martyrdom and betrayal, in a spiritual ordeal that lifts the film’s earthy drama to the plane of religious allegory. With stark, visceral cinematography that pits blinding white snow against pitch-black despair, The Ascent finds poetry and transcendence in the harrowing trials of war. (From Criterion collection edition).