The melting of ice in the Arctic Ocean continues to affect not only maritime transportation but also global geopolitics. As the ice melts, Anglo-Saxon maritime dominance also melts. In this context, a new development that will be a milestone for world maritime trade took place on September 25, 2024, on the Northern Sea Route (NSR) controlled by Russia in the Arctic Ocean.

A First on the North Arctic Route

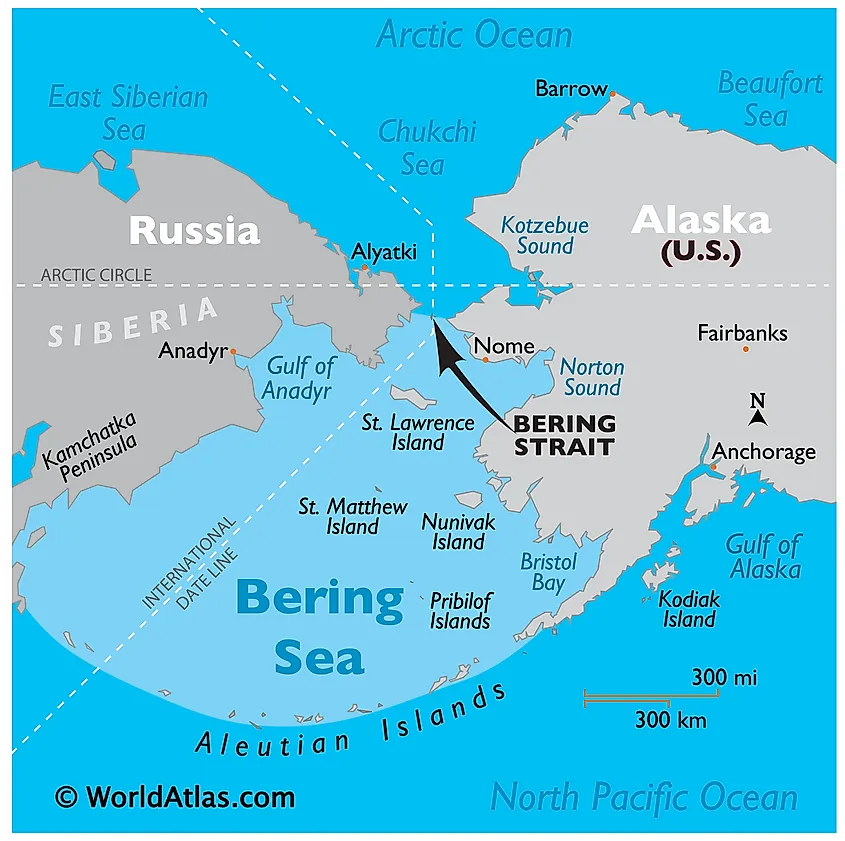

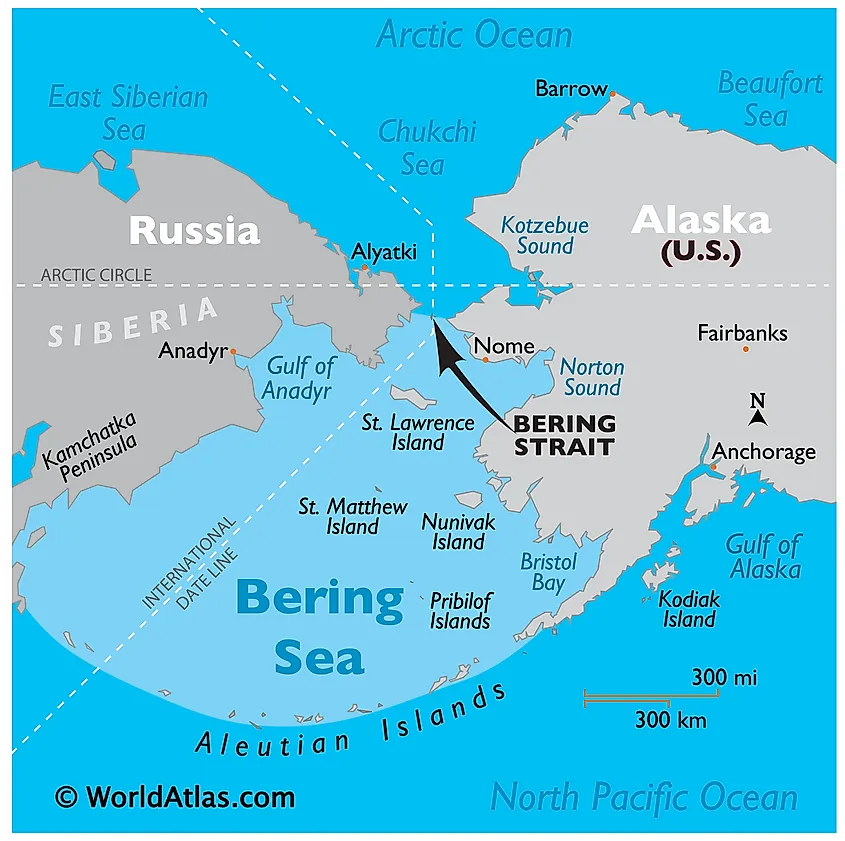

The Panama-flagged, non-Ice Class, 294-meter-long PANAMAX-class container ship named ‘’Flying Fish 1’’ carrying 5,000 containers (TEU) arrived in Shanghai, China, on September 25, 2024, less than three weeks after its departure from Saint Petersburg, Russia. During this 8,000-mile voyage, the ship maintained an average speed of 16 knots and, most importantly, did not need the Russian icebreaker. The two most critical developments for this journey, which goes from the Baltic to the North Sea and passes through the Barents, Kara, Laptev, East Siberian, Chukchi and Bering Seas, are undoubtedly Russia’s announcement that the NSR will be open to ice-class ships all year round at the end of 2022, and starting in 2023, non-ice-class ships will be given permission to pass between July 1 and November 15. The Flying Fish 1 ship received this permission on May 20, 2024.

By Schiffswelt via Vessel Finder

The first container ship to pass through these waters in history was the 45,000-ton container ship named Venta Maersk, owned by the world container giant Maersk. The ship loaded the containers from Vladivostok in the Pacific and brought them to Saint Petersburg in the Baltic within a month on September 28, 2018 via the NSR.

NSR in Energy Transportation

While these were happening in the container world, the Russian Arc7 class Christophe de Margerie (Ice Class) LNG tanker (liquefied natural gas carrier) departed from Jiangsu, China on January 27, 2021 and completed its 2400-mile journey via the NSR in 11 days on February 8, 2021 at the Sabetta Port in the Arctic/Kara Sea of Russia. The same ship had used the same route in May 2020 in the east direction under icebreaker escort. This passage, which was made in February 2020 in winter conditions, in continuous darkness, without icebreaker escort for the most part, took 36 days shorter than the journey to be made via the Suez Canal. With this journey, Russia proved that passage in the region can be realized in almost 10 months out of 12 months. Most importantly, Russia’s possession of the world’s largest and most powerful nuclear icebreakers capable of breaking 4-meter ice causes it to establish a monopoly in the region within its own jurisdiction. These types of ships are capable of breaking ice wide enough for 200,000-ton supertankers to pass.

Shortened Routes

If Flying Fish 1, which arrived in Shanghai on September 25, had used the Suez Canal, it would have covered 12,000 miles and the journey would have taken two weeks longer. On the other hand, many ships that cannot use the Bab El Mandeb Strait and the Suez Canal due to the Houthi attacks that emerged through the Israel-Hamas war have been making this journey by circling the Cape of Good Hope since November 2023. This takes approximately 16,000 miles. Therefore, the NSR offers a solution that reduces operating costs for existing operators by half compared to the Cape of Good Hope route with the 8,000 miles it saves.

The RF nuclear icebreaker Artika was the first surface ship to reach the North Pole on August 17, 1977.

Transition to Regular Lines

Seasonal fixed lines have now begun to be established between China and Russia. In the summer of 2023, the 170,000-ton Capesize bulk carrier Gingo and numerous Suezmax crude oil tankers passed through this route. With 14 consecutive shipments made with ice-free tankers, Russia sent 1.5 million barrels of oil to China. Oil is the strategic material that China will need the most due to the closure of the Strait of Malacca in times of war. Russia is proving that it will send the oil it will need the most to China through the Arctic by tankers, not only through pipelines or train transportation elsewhere. In 2023, 36 million tons of cargo were carried in the NSR, which operates under the authority of ROSATOM.

Dollar and Navy Power

The situation that emerged in the NSR is a nightmare for Anglo-Saxon maritime geopolitics. Because the NSR is turning into a permanent maritime transportation route where American warships cannot control. The US maintained its dollar power with its navy. Today its navy is inadequate in the NSR area. In addition, its navy has weakened beyond shrinking. However, what the founder of the CIA organ Stratfor’s founder, strategist George Friedman, say in his books “The Next 100 Years” and “The Next 10 Years”, which he wrote in the 2010s when American power was not questioned?

Nuclear icebreaker Tor sitting in Siberian port of Sabetta

“The foundation of American power is the oceans. Dominating the oceans prevents other states from attacking the US, allows the US to intervene when necessary, and gives the US control of international trade. Global trade is dependent on the oceans. Whoever controls the oceans controls global trade… The US controls all the oceans. No other power in history has been able to do this. This control is not only the foundation of US security, but also the foundation of its power to shape the international system. If the US does not approve, no one can go anywhere on the seas. At the end of the day, maintaining control of the world’s oceans is the most important geopolitical goal for the US.”

This situation has changed now. The US dollar and naval power are no longer sufficient for the dominance of hegemony.

Crude Oil Reaching From the Sea Is Essential

Both world wars broke out because of Germany, which went from the continent to the sea and challenged the hegemonic England. If we add Japan, which wanted to expand from the island to the continent in World War II, the struggle focused on the control of the seas for both in the final analysis. Hitler could not control the seas with submarines alone. Hitler’s submarines could not keep up with the speed of the US’s shipbuilding. Japan, as an island state, was also dependent on oil and without controlling the seas, oil continuity was not possible. It was exhausted when it lost its merchant fleet. In short, both Germany and Japan could not use the sea, and were left without oil and could not fight. Although oil pipelines exist today, it is easy to destroy these lines in war. Even if they are repaired, it is not easy to prevent repeated attacks. Therefore, Friedman draws the power of his interpretation from history. However, that power is weakening today. When World War II ended, there were 6,000 ships, today there are 297.

Russia’s Geographical Advantage in the Arctic

In 2019, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said,

“The Arctic is no longer an area of cooperation, all countries in the region must be prepared for the fact that it has become a region for competition, and that China and Russia are essentially ‘threats to security’ in the region.”

In 2019, regular transportation lines had not yet been established, and the NSR had not been opened to world trade. Today, the situation is very different.

With the formation of regular lines on the Arctic front and the regular passage of container ships suitable for military buildup, a permanent crisis has begun for the Anglo-Soxon front, but Russia has the advantage in this crisis.

Because only 12% of the Arctic Ocean is in the status of high seas. Of the remaining 88%, 65% (24,000km of coast) is under the full control of Russia. 67% of the Russian Navy belongs to the Northern Fleet, as the most important coasts that open to the oceans, especially nuclear submarines, are in the North Sea. The main base of the Northern Navy is also in this region. However, the biggest nightmare for the US is that Russia has 11 large-tonnage icebreakers/tugboats in the region, 8 of which have Nuclear propulsion. This superiority gives the Russians a clear advantage over the USA, which has 2 conventional icebreakers.

Russia’s Infrastructure Build

At an economic forum at the beginning of 2024, Russian President Putin said that “the center of economic development in Russia is changing, Russia will expand with the Arctic.” Indeed, the region contains 30% of the world’s natural gas reserves and 13% of oil.

Russia first established the Arctic Command in the region, which can be considered its front yard. It established a chain of modern bases extending from the north of the Kola Peninsula to Franz Joseph Land and to Wrangel Island in the east. Russia built a large airport with a 4 km long runway in the Arctic region. Air bases were developed, early warning radars and listening systems were modernized, and the number of aircraft was increased. In addition, a 6,000-person emergency response force was established in the Murmansk and Yamal regions.

China Is a Geopolitical Actor in the Arctic

China defines itself as a Near Arctic State. It does not only have geopolitical interests in the region. It has many common investments with Russia, especially in energy and rare metals.

In 2015, China identified the Bering Strait, the Pacific and Atlantic gateway to the Arctic Ocean, as an area of China’s security concern and declared that it would use force if necessary to protect its interests in this strait. In mid-September 2015, for the first time in history, five Chinese warships exercised the right of innocent passage in the Bering Sea. If China uses the Bering Strait and other Arctic routes, it can both largely get rid of its dependence on the Strait of Malacca and save $60-100 billion annually in maritimetransportation costs.

China is also developing energy cooperation with Russia in the Arctic Ocean within the scope of BRICS and the SCO. Russian Gazprom and China’s CNPC companies continue drilling in the Arctic Ocean. China’s main goal is to include the region in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) under the name of the Polar Silk Road. After the Russia-Ukraine War, China’s cooperation with Russia in the Arctic region has developed rapidly. For example, in July of this year, Russian and Chinese bomber aircraft conducted joint patrol operations off the coast of Alaska. Similarly, in October, Chinese and Russian coast guard ships passing through the Bering Strait conducted joint exercises and patrols in Arctic waters for the first time in history.

The Reaction of the Anglo-saxon Front

It should be emphasized that the maritime hegemony is very disturbed by these developments. In July 2024, the US updated its Arctic Strategy. Before the new document, which aims to develop surveillance, intelligence and military cooperation in order to counter Russia and China, during the Trump era, the US Navy Department published a strategy document for the region under the name Blue Arctic on January 5, 2021.

In addition to the Russian Federation, the Arctic region has coasts with the US, Canada, Norway and Denmark. On the other hand, there is an 8-member Arctic Council established in 1996, where 3 northern (Nordic) countries (Sweden, Finland and Iceland) are represented, which provides regulation and coordination in the region. The Council has been inactive since February 2022 due to the Russia-Ukraine War. On the other hand, 7 out of 8 countries are NATO members. However, this situation does not give NATO a situational advantage. The US and its allies continue to pay the price of the rapid downsizing at sea and in the region after the Cold War. They are falling behind in both the number of icebreakers and the number of troops ready for war in winter conditions.

In addition, Russia has advantages in the field of submarine warfare and hypersonic anti-ship missiles. However, despite its limited naval power, the US challenges Russia’s geographical superiority in these critical waterways through its allies. As the only NATO country with a permanent military headquarters north of the Arctic Circle (66°33’N latitude), Norway gives its most important security and defense priority to the protection of US interests in this region due to the newly developing Arctic geopolitics. NATO also uses Norway’s situation as a battering ram against Russia, putting it forward for the interests of the US in this region. Norway, one of the calmest, richest and most prosperous countries in the world, has now joined the group of risky countries that have to maintain high military vigilance and readiness at all times. In this context, some American strategists have drawn attention to the area between England, Greenland and Iceland, which is called the GIUK Gap where Russian submarines have to pass to reach Atlantic Ocean. US has established the (underwater) SOSUS system during the cold war to monitor Soviet subs movements. Today GIUK Gap is more important than that of the cold war era. In this context the Nuclear Submarine base in Faslane/Scotland is the most valuable asset of US Navy in time of armed conflict with Russia. The speedy accessions of Sweden and Finland to NATO has to be seen in Arctic perspective also.

It is also said that the Bering Strait has emerged as a new rival to the critical junction where Russian nuclear and diesel-electric submarines pass. In this region, the revival of the American base chain in Alaska and the Aleuatian Islands is demanded. In addition to these developments, the joint NATO headquarters JFC Norfolk has also taken responsibility for the Norwegian Arctic region.

The Nordic Council and Zelensky

The Northern (Nordic) Council, established in 1952 by Denmark, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, also intervenes in Arctic policies on environmental and maritime law issues. In the four-day meeting focusing on “Peace and Security in the Arctic” that started on October 27, 2024, the Council prioritized security concerns and perceived “threats” from Russia and China, while also moving into the geopolitical arena by inviting Zelensky to the meeting.

Lessons for Turkiye

Undoubtedly, one of the most important developments of the 21st century is the opening of the Arctic sea route while American hegemony is declining. How active is Turkey in this region?

Although our shipyards follow the developments in the Arctic Region and take some initiatives, our Merchant Marine Fleet is not active in this field. In this conjuncture, where the maritime dominance of the Anglo-Saxon world is coming to an end, or at least a strong Asia/Global South counterbalance is emerging, new areas of opportunity should be evaluated.At the very least, the merchant fleet needs to formulate Arctic policy, as do some of our enterprising shipyards. Because this road will be an area where many operators will try to take a place. While Turkiye-Russia relations are developing in many areas despite our NATO membership and the pressures of the Ukraine War, the opportunities that arise on the Arctic Route should not be overlooked. Due to the US and the EU, which do not allow Ankara to explore for and extract gas and oil in the Mediterranean, Ankara sent a seismic research ship and frigates to Somalia which is 4600 miles away under US/EU pressure.

On the other hand the NSR, is 3000 km to our north and provides new opportuniteis for cooperation with Russia. Reminding that ROSATOM, which built a nuclear reactor in Mersin Akkuyu, is also the NSR Operation Authority, it is important to start bilateral agreements and infrastructure investment partnerships with Russia on the NSR Transportation Route to prepare for the remaining quarters of the 21st century. Our shipowners should also evaluate this rising opportunity and show their flag, albeit slowly, on this line by having Ice Class ships.

*

Click the share button below to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Don’t Miss Out on Global Research Online e-Books!

Ret Admiral Cem Gürdeniz, Writer, Geopolitical Expert, Theorist and creator of the Turkish Bluehomeland (Mavi Vatan) doctrine. He served as the Chief of Strategy Department and then the head of Plans and Policy Division in Turkish Naval Forces Headquarters. As his combat duties, he has served as the commander of Amphibious Ships Group and Mine Fleet between 2007 and 2009. He retired in 2012. He established Hamit Naci Blue Homeland Foundation in 2021. He has published numerous books on geopolitics, maritime strategy, maritime history and maritime culture. He is also a honorary member of ATASAM.

He is a regular contributor to Global Research.

Featured image is from Rosatom via High North News

The original source of this article is Global Research

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License •

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License •