The Fact-Checked Adventures of Brian Williams

BY ANDY BOROWITZ

MEDIA CRITIQUES

NEW YORK (The Borowitz Report) — The fact-checking department at NBC News has verified that the following anecdotes told by Brian Williams actually happened.

1. In August of 2003, I boarded a helicopter to Steven Spielberg’s house in East Hampton. Once we were up in the air, I was alarmed to discover that there was no bottled water on board. I commanded the pilot to make an emergency landing.

SEE OUR APPENDIX FOR BRIAN WILLIAMS’S EMBARRASSING ADMISSION OF LYING WHILE REPORTING FROM IRAQ

2. In November of 2007, I boarded a Cadillac Escalade to attend the annual gala of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Not until I arrived at my destination did I realize that the driver had closed the door on my Armani coat. I was able to have it successfully dry-cleaned, but that was a close one.

3. In March of 1998, I fell asleep on my tanning bed. I could have been burnt to a crisp. Fortunately, I woke up in the nick of time, but the people at the spa had needlessly endangered me. I started going to a new spa.

4. In May of 2011, the elevator in my building suffered an equipment malfunction en route to my penthouse. I was stuck talking to a tax attorney for seven minutes before I was rescued.

5. While in Sochi for the Olympics last year, I ordered dinner from room service. I don’t know if it was the oysters or the caviar, but something had gone bad. I was hurling all night.

6. In December of last year, I had to attend a live broadcast of “Peter Pan.” It was worse than I expected, but I was trapped for two hours with no way out.

Get news satire from The Borowitz Report delivered to your inbox.

appendix

EXCLUSIVE REPORT

NBC’s Brian Williams recants Iraq story after soldiers protest

By Travis J. Tritten | Stars and Stripes | Published: February 4, 2015

UPDATE | Williams’ apology leaves out key details of Iraq incident

The admission came after crew members on the 159th Aviation Regiment’s Chinook that was hit by two rockets and small arms fire told Stars and Stripes that the NBC anchor was nowhere near that aircraft or two other Chinooks flying in the formation that took fire. Williams arrived in the area about an hour later on another helicopter after the other three had made an emergency landing, the crew members said. “I would not have chosen to make this mistake,” Williams said. “I don’t know what screwed up in my mind that caused me to conflate one aircraft with another.” Williams told his Nightly News audience that the erroneous claim was part of a “bungled attempt” to thank soldiers who helped protect him in Iraq in 2003. “I made a mistake in recalling the events of 12 years ago,” Williams said. “I want to apologize.” Williams made the claim about the incident while presenting NBC coverage of the tribute to the retired command sergeant major at the Rangers game Friday. Fans gave the soldier a standing ovation. “The story actually started with a terrible moment a dozen years back during the invasion of Iraq when the helicopter we were traveling in was forced down after being hit by an RPG,” Williams said on the broadcast. “Our traveling NBC News team was rescued, surrounded and kept alive by an armor mechanized platoon from the U.S. Army 3rd Infantry.” Williams and his camera crew were actually aboard a Chinook in a formation that was about an hour behind the three helicopters that came under fire, according to crew member interviews. That Chinook took no fire and landed later beside the damaged helicopter due to an impending sandstorm from the Iraqi desert, according to Sgt. 1st Class Joseph Miller, who was the flight engineer on the aircraft that carried the journalists. “No, we never came under direct enemy fire to the aircraft,” he said Wednesday. The helicopters, along with the NBC crew, remained on the ground at a forward operating base west of Baghdad for two or three days, where they were surrounded by an Army unit with Bradley fighting vehicles and Abrams M-1 tanks. Miller said he never saw any direct fire on the position from Iraqi forces. The claim rankled Miller as well as soldiers aboard the formation of 159th Aviation Regiment Chinooks that were flying far ahead and did come under attack during the March 24, 2003, mission. One of the helicopters was hit by two rocket-propelled grenades — one did not detonate but passed through the airframe and rotor blades — as well as small arms fire. “It was something personal for us that was kind of life-changing for me. I know how lucky I was to survive it,” said Lance Reynolds, who was the flight engineer. “It felt like a personal experience that someone else wanted to participate in and didn’t deserve to participate in.” Reynolds said Williams and the NBC cameramen arrived in a helicopter 30 to 60 minutes after his damaged Chinook made a rolling landing at an Iraqi airfield and skidded off the runway into the desert. He said Williams approached and took photos of the damage, but Reynolds brushed them off because the crew was assessing damage and he was worried that his wife, who was alone in Germany, might see the news report. “I wanted to tell her myself everything was all right before she got news of this happening,” Reynolds said. The NBC crew stayed only for about 10 minutes and then went to see the Army armored units that had been guarding the nearby Forward Operating Base Rams and came out to provide a security perimeter around the aircraft. Tim Terpak, the command sergeant major who accompanied Williams to the Rangers game, was among those soldiers, and the two struck up a friendship. Miller, Reynolds and Mike O’Keeffe, who was a door gunner on the damaged Chinook, said they all recall NBC reporting that Williams was aboard the aircraft that was attacked, despite it being false. The NBC online archive shows the network broadcast a news story on March 26, 2003, with the headline, “Target Iraq: Helicopter NBC’s Brian Williams Was Riding In Comes Under Fire.” Williams disputed Wednesday claims the initial reports were inaccurate, saying he originally reported he was in another helicopter but later confused the events. In a 2008 NBC blog post with his byline, he wrote that the “Chinook helicopter flying in front of ours (from the 101st Airborne) took an RPG to the rear rotor.” O’Keeffe said the incident has bothered him since he and others first saw the original report after returning to Kuwait. “Over the years it faded,” he said, “and then to see it last week it was — I can’t believe he is still telling this false narrative.”

What is $1 a month to support one of the greatest publications on the Left?

“American Sniper,” Clint Eastwood and White Fear

The Insecurities of Empire

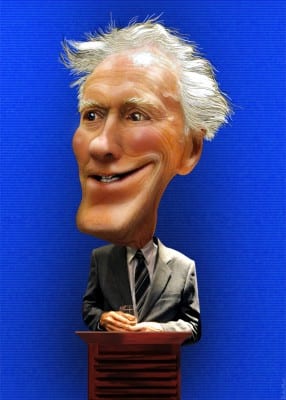

Eastwood as Gunny Sgt. in the ludicrous Heartbreak Ridge (1986). His disingenuous, mawkish glorification of the military is a lifelong passion usually denied. (Warner Bros.)

by JOSEPH E. LOWNDES, COUNTERPUNCH

[dropcap]L[/dropcap]iberal writers have been lining up for the last month to decry American Sniper along predictable, ideologically comfortable lines. “Macho Sludge” was the title of an Alternet piece by David Masciotra. Chris Hedges called it “a grotesque hypermasculinity that banishes compassion and pity.” These reviewers, driven perhaps by their own political distaste of American Sniper miss much – or most of what is at work politically in the film. Straight propaganda rarely makes for compelling entertainment, so the enormous popularity of American Sniper (hauling in $30.6 million in its fourth weekend to total to nearly $250 million in 17 days of broad release) suggests that it has reached far beyond the hard core of ultraconservatives one would expect to embrace the film these reviewers describe.

Let’s start with Clint Eastwood himself, who says that American Sniper was meant to criticize war. “The biggest antiwar statement any film” can make is to show, he said, “the fact of what [war] does to the family and the people who have to go back into civilian life like Chris Kyle did.” There are two Eastwoods in the popular imagination – the celebrant of violence in the Sergio Leone “spaghetti westerns” and the Dirty Harry movies; and the lamenter of violence in films such as Unforgiven and Gran Torino. But as American Sniper demonstrates, those two modes are not so far apart. Eastwood does here what he has done repeatedly in his career – resolves his hero’s ambivalence, psychic pain, and sense of structural powerlessness through masculine honor, sacrifice, and vulnerability (often played out on a highly racialized landscape).

Eastwood hit on this formula in one of the first films he directed, The Outlaw Josey Wales. In that film a poor farmer in the Missouri Territory becomes a Confederate guerilla when his home is attacked by Union soldiers. Like the protagonist of American Sniper (Chris Kyle) seeing the World Trade Center come down, Josey Wales sees no choice but to take up arms, and in so doing proves to be an lowndesunusually good, if reluctant, marksman and killer. In both films, the purposes of war remain ambivalent. Both Wales’s and Kyle’s challenge, ultimately is to work out a postwar existence. As Josey says to a Comanche warrior, “Dyin’ ain’t so hard for men like us . . . its living that’s hard.”

The Outlaw Josey Wales, released in 1976, had an anti-government politics that appealed to an American public by expressing sentiments on both left and right. It came on the heels of both the Vietnam War and Watergate, and reflected popular disillusionment with both. Yet its Confederate, anti-statist hero also anticipated insurgency on the right. When promoting the film, Eastwood always mentioned Vietnam and Watergate, and the kind of profound distrust that had developed toward government at the time. But his sentiment was not just that of an opponent of the war and the Nixon administration; he was openly, angrily anti-statist in a way that blamed not only the government but impoverished recipients of government assistance. As he told one audience, “Today we live in a welfare-oriented society, and people expect more from Big Daddy Government, more from Big Daddy Charity. That philosophy never got you anywhere. I worked for every crust of bread I ever ate.” It was the state and people of color who ultimately violated Josey Wales and his family, even though he makes common cause with a Cherokee against imperial expansion of the US state. It is political ambivalence that made The Outlaw Josey Wales popular with a broad public, not unlike American Sniper.

In reference to a scene in the film Sudden Impact where a white man trains his gun at the head of a black man holding a white woman at knifepoint, the late political theorist Michael Rogin wrote that a fantasized demonic love triangle between women, blacks, and the state authorized the rage of white men in Reagan-era America. But unlike Dirty Harry Callahan, both Josey Wales and Chris Kyle evince a woundedness, and ultimately a kind of powerlessness that does not re-establish white male hegemony. It is this sense that American Sniper is deeply reactionary even as it articulates no clear political vision.

One can see, in Eastwood’s rendering of Chris Kyle, that his desire – his need – to be a killer of almost superhuman proportions makes him not sociopathic, but rather a “sheepdog,” someone operating in a state of anxious alertness at all times against inevitable attack. His violence is justified in advance. Kyle provides protection from the chaotic aggression of people of color (just as the real-life Kyle told stories about picking off bad guys from the roof of the Superdome during Hurricane Katrina).

It is neither male bravado nor triumphant nationalism that compels viewers to sympathize with Chris Kyle. But nor is it an antiwar film. It is rather an assertion of both the grim inevitability of certain kinds of violence, and of our obligation to those who wage violence for that very reason. It is this logic that brings together the violence and anti-violence in Eastwood’s oeuvre, as well as his seeming anti-racism and racism.

We can see this logic of white fear and vulnerability echoed by the recently publicized cases of police who have killed African unarmed African Americans, and by those who support them. Think of the testimony of Darren Wilson: “I felt like a five-year-old holding onto Hulk Hogan.” Or better yet think of Police Benevolent Association President Patrick Lynch defending Daniel Pantaleo, the cop who killed Eric Garner with an illegal chokehold on Staten Island: “Garner’s death was a tragedy for Garner’s family,” he said. “It’s also a tragedy for a police officer who has to live with that death.” Pantaleo, Lynch went on, “is literally, literally an Eagle Scout, and I think that story isn’t being told. That a New York City police officer went out and did a difficult job, a job where there’s no script, and sometimes with that, a tragedy comes.”

American Sniper need not directly claim a link between 9/11 and Iraq, it need not subscribe to the Chris Kyle’s claim that Iraqis are “savage” and “evil.” One could easily read both as meant to convey the narrow, provincial perception of the protagonist. It need not even endorse any American presence in the Middle East at all. American Sniper dispenses with conventional politics to portray the raw, emotional core of white vulnerability. James Baldwin once wrote that the monstrous violence visited by white Americans on the world is due to this people having opted for safety over life. American Sniper, attending to the triple insecurities of race, gender, and empire, serves is an exclamation point to that observation.

Joseph E. Lowndes is assistant professor of political science, University of Oregon. He is the author of From the New Deal to the New Right: Race and the Origins of Modern Conservatism. He lives in Eugene.

What is $1 a month to support one of the greatest publications on the Left?

A Short History of Sniper Cinema

DI instilling the USMC brand of discipline. Blind obedience is key to making soldiers into unthinking robots. Those, like Kyle, who bring their own sociopathies to the task, may excel in the field and remain undisturbed by the horrors they commit. (Full Metal Jacket, Warner Bros.)

[dropcap]The $60 million[/dropcap] Warner Bros.-Clint Eastwood war film American Sniper follows the exploits of Chris Kyle, a United States Navy SEAL who was sent to Iraq to, according to the official Warners website, “protect his brothers-in-arms.” As a military sniper, “[h]is pinpoint accuracy saves countless lives on the battlefield and, as stories of his courageous exploits spread,” continues the website, “he earns the nickname ‘Legend.’” By the real Kyle’s own accounts, the U.S. Navy credited this “legend” with “160 kills” [1].

There was a time not long ago when anyone bragging about “kills” was not the sort of person we would admire – much less pay to see sympathetically portrayed in a major Hollywood movie. This was especially true in the case of the sniper who, even in politically reactionary circles, was generally perceived as sadist, psychopath, and coward. Even Warner Bros. and Clint Eastwood shared this viewpoint at one time.

Eastwood in one of his early signature roles, Dirty Harry. Even then his cinematic persona was that of a crypto fascist cop or cold killer. Wasn’t he really aware he was making that archetype popular? (Warner Bros.)

In Don Siegel’s 1971 thriller Dirty Harry, Eastwood made his first appearance as Inspector Harry Callahan of the San Francisco Police Department. A great success for Warners, the picture was heavily criticized for what many considered to be a fascistic political outlook regarding law enforcement as Eastwood’s Callahan regularly ignored the rulebook and civil liberties protocols in order to deliver Hollywood-style justice with a .44 Magnum [2]. (The liberal Siegel later insisted he did not condone the behavior of the protagonist [3].) And while the villain of the narrative, “Scorpio,” whose most distinguishable clothing statement was a peace sign belt buckle, symbolized an establishment backlash against the hippie/radical movement of the era, the character was in fact based on San Francisco’s notorious Zodiac serial killer (the subject of director David Fincher’s 2007 movie Zodiac).

So what were the horrible crimes Scorpio (Andy Robinson) committed that so disgusted Inspector Harry Callahan and his ultra- conservative movie audiences back in the early 1970s?

conservative movie audiences back in the early 1970s?

Scorpio, like the real-life Zodiac killer, was a sniper. In the opening sequence we see him killing, from a great distance with a scope rifle, a young woman. She, of course, has no clue she is about to be murdered. With the assassination of President John F. Kennedy still a recent and harrowing memory, the U.S. public had good reason to fear and despise snipers.

Flash-forward to 2014-2015 where we find the media and moviegoers fawning over a new Warner Bros.-Clint Eastwood movie (this time directed by Eastwood) in which a military sniper is portrayed as an heroic martyr. What a difference half-a-century makes. Compare this current studio epic with cinematic sniper portrayals from earlier decades and generations.

In director John Ford’s World War I drama The Lost Patrol (RKO Radio Pictures, 1934), which in recent years has been cited for its imperialist racism, an Arab sniper randomly kills soldiers of a British desert patrol in Mesopotamia [4]. In Full Metal Jacket (Warner Bros., 1987), Stanley Kubrick’s centrist/conservative take on the Vietnam war, a North Vietnamese woman sniper fires upon and kills numerous U.S. Marines in Hue during the 1968 Tet offensive. (Earlier in the film, with tongue firmly planted in cheek, Kubrick showed a sadistic Marine drill instructor extolling the virtues of ex-Marine-turned-sniper Charles Whitman, who killed sixteen people during a 1966 Texas shooting spree.)

In Fred Zinnemann’s meticulously crafted Day of the Jackal (1973), the contract assassin (Edward Fox) has none other than Charles de Gaulle, the president of France, in his crosshairs. (Universal)

On the opposite side of the political spectrum, British filmmaker Ken Loach presented an enemy priest as a pro-fascist sniper in Land and Freedom, his 1995 left-wing drama of the Spanish Civil War. And while the protagonist of Fred Zinnemann’s 1973 spy thriller The Day of the Jackal (Universal) is an assassin who plans, in 1963, a sniper rifle killing of President Charles De Gaulle, the character and his actions are designed to arouse morbid curiosity rather than outright audience endorsement. (Michael Caton-Jones crudely updated Zinnemann’s film in his 1997 Universal thriller The Jackal, which also took a disapproving view of snipers.)

Other memorable films about snipers, or would-be snipers, have used the subject matter to probe deeper into everything from the all-American obsession with guns (Peter Bogdanovich’s 1968 independent feature Targets) to the deadly role of the sniper in political terrorism (Lewis Allen’s 1954 thriller Suddenly and John Frankenheimer’s 1962 dark political satire, The Manchurian Candidate). A particularly underrated film from this genre is Edward Dmytryk’s The Sniper (Columbia, 1952), a film noir made after the director informed on former associates following a prison sentence as a member of the “Hollywood Ten.” Produced for the liberal Stanley Kramer, The Sniper centers on a young psychopath (Arthur Franz) in San Francisco who tries and fails to curb his urge to kill women with his sniper’s rifle. What distinguishes this film from most other Hollywood productions on the subject is its efforts to get to the roots of the sniper’s sickness, with a city psychiatrist (Richard Kiley) advocating on behalf of preventive social measures.

These are by no means exceptions to the Hollywood rule, in both feature films and network television series, of depicting snipers as serious threats to humanity. Such depictions are not quaint examples from bygone eras when we consider the anti-sniper themes emerging from time to time in more recent TV series as Bones and 24 as well as the 2012 action epic Jack Reacher.

The ongoing problem with visualizing the sniper on screen in a graphic manner is the inevitable risk that the wrong audience member will regard the proceedings as a tutorial. Luis Buñuel brilliantly resolved this problem in his 1974 absurdist comedy The Phantom of Liberty, in which a rooftop sniper is never shown actually pulling the trigger of his rifle. We see only innocent passersby falling without so much as the sound of a single gunshot.

It can only be hoped that American Sniper will not set the tone for future Hollywood movies in which “sharpshooters” are portrayed heroically.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Max Alvarez is a film historian who was a visiting scholar for The Smithsonian Institution between 1997-2009. He is author of The Crime Films of Anthony Mann (University Press of Mississippi) and a major contributor to Thornton Wilder/New Perspectives (Northwestern University Press). His website is: www.maxjalvarez.com

Sources

[1] Adam Bernstein, “Chris Kyle, Navy Seal [sic] and author of ‘American Sniper,’ dies,” Washington Post (February 3, 2013): http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/chris-kyle-navy-seal-and-author-of-american-sniper-dies/2013/02/03/f838bcfc-6e22-11e2-ac36-3d8d9dcaa2e2_story.html

[2] Roger Ebert, “Dirty Harry,” Chicago Sun-Times (December 29, 1971).

[3] B. Drew, “The Man Who Paid His Dues,” American Film Magazine December 1977/January 1978.

[4] Jack G. Shaheen addresses the bigotry in his book, Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People (New York: Olive Branch Press, 2001), p. 309.

What is $1 a month to support one of the greatest publications on the Left?

Killing Ragheads for Jesus: On Watching ‘American Sniper’

[dropcap]“American Sniper”[/dropcap] lionizes the most despicable aspects of U.S. society—the gun culture, the blind adoration of the military, the belief that we have an innate right as a “Christian” nation to exterminate the “lesser breeds” of the earth, a grotesque hypermasculinity that banishes compassion and pity, a denial of inconvenient facts and historical truth, and a belittling of critical thinking and artistic expression. Many Americans, especially white Americans trapped in a stagnant economy and a dysfunctional political system, yearn for the supposed moral renewal and rigid, militarized control the movie venerates. These passions, if realized, will extinguish what is left of our now-anemic open society.

The movie opens with a father and his young son hunting a deer. The boy shoots the animal, drops his rifle and runs to see his kill.

“Get back here,” his father yells. “You don’t ever leave your rifle in the dirt.”

“Yes, sir,” the boy answers.

“That was a helluva shot, son,” the father says. “You got a gift. You gonna make a fine hunter some day.”

The camera cuts to a church interior where a congregation of white Christians—blacks appear in this film as often as in a Woody Allen movie—are listening to a sermon about God’s plan for American Christians. The film’s title character, based on Chris Kyle, who would become the most lethal sniper in U.S. military history, will, it appears from the sermon, be called upon by God to use his “gift” to kill evildoers. The scene shifts to the Kyle family dining room table as the father intones in a Texas twang: “There are three types of people in this world: sheep, wolves and sheepdogs. Some people prefer to believe evil doesn’t exist in the world. And if it ever darkened their doorstep they wouldn’t know how to protect themselves. Those are the sheep. And then you got predators.”

Why is Hollywood Rewarding Clare Danes and Mandy Patinkin for Glamorizing the CIA? • Filmmaker Robert Greenwald: American Sniper is a Neocon Fantasy • A Tale of Two Snipers • How Clint Eastwood Ignores History in American Sniper

The camera cuts to a schoolyard bully beating a smaller boy.

“They use violence to prey on people,” the father goes on. “They’re the wolves. Then there are those blessed with the gift of aggression and an overpowering need to protect the flock. They are a rare breed who live to confront the wolf. They are the sheepdog. We’re not raising any sheep in this family.”

The father lashes his belt against the dining room table.

“I will whup your ass if you turn into a wolf,” he says to his two sons. “We protect our own. If someone tries to fight you, tries to bully your little brother, you have my permission to finish it.”

There is no shortage of simpletons whose minds are warped by this belief system. We elected one of them, George W. Bush, as president. They populate the armed forces and the Christian right. They watch Fox News and believe it. They have little understanding or curiosity about the world outside their insular communities. They are proud of their ignorance and anti-intellectualism. They prefer drinking beer and watching football to reading a book. And when they get into power—they already control the Congress, the corporate world, most of the media and the war machine—their binary vision of good and evil and their myopic self-adulation cause severe trouble for their country. “American Sniper,” like the big-budget feature films pumped out in Germany during the Nazi era to exalt deformed values of militarism, racial self-glorification and state violence, is a piece of propaganda, a tawdry commercial for the crimes of empire. That it made a record-breaking $105.3 million over the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday long weekend is a symptom of the United States’ dark malaise.

Eastwood: Master of cheap martial sentimentality. The man has fooled millions of people, and even the French—in a signal of their own cultural rot— regard him as a legitimate auteur. He was awarded two of France’s highest honors: in 1994 he became a Commandeur of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres and in 2007 he was awarded the Légion d’honneur medal. In 2000, he was awarded the Italian Venice Film Festival Golden Lion for lifetime achievement. The disease represented by Eastwood—marking the apogee of American cultural influence— is global. (DonkeyHotey, flickr)

“The movie never asks the seminal question as to why the people of Iraq are fighting back against us in the very first place,” said Mikey Weinstein, whom I reached by phone in New Mexico. Weinstein, who worked in the Reagan White House and is a former Air Force officer, is the head of the Military Religious Freedom Foundation, which challenges the growing Christian fundamentalism within the U.S. military. “It made me physically ill with its twisted, totally one-sided distortions of wartime combat ethics and justice woven into the fabric of Chris Kyle’s personal and primal justification mantra of ‘God-Country-Family.’ It is nothing less than an odious homage, indeed a literal horrific hagiography to wholesale slaughter.”

Weinstein noted that the embrace of extreme right-wing Christian chauvinism, or Dominionism, which calls for the creation of a theocratic “Christian” America, is especially acute among elite units such as the SEALs and the Army Special Forces.

The evildoers don’t take long to make an appearance in the film. This happens when television—the only way the movie’s characters get news—announces the 1998 truck bombings of the American embassies in Dar es Salaam and Nairobi in which hundreds of people were killed. Chris, now grown, and his brother, aspiring rodeo riders, watch the news reports with outrage. Ted Koppel talks on the screen about a “war” against the United States.

“Look what they did to us,” Chris whispers.

He heads down to the recruiter to sign up to be a Navy SEAL. We get the usual boot camp scenes of green recruits subjected to punishing ordeals to make them become real men. In a bar scene, an aspiring SEAL has painted a target on his back and comrades throw darts into his skin. What little individuality these recruits have—and they don’t appear to have much—is sucked out of them until they are part of the military mass. They are unquestioningly obedient to authority, which means, of course, they are sheep.

“There is no shortage of simpletons whose minds are warped by this belief system,” warns Hedges, and he’s absolutely right. But we say, please include Eastwood in this breed, or put him down as a cynical exploiter of this severely damaged mentality. It is he who concocted this insalubrious brew, this cryptofascist love song, and meticulously supervised every inch of its footage, along with Bradley Cooper, a fellow who apparently chose to see only the career potential of the role. Separating these men from the end product would constitute critical malpractice.—Eds.

We get a love story too. Chris meets Taya in a bar. They do shots. The movie slips, as it often does, into clichéd dialogue.

She tells him Navy SEALs are “arrogant, self-centered pricks who think you can lie and cheat and do whatever the fuck you want. I’d never date a SEAL.”

“Why would you say I’m self-centered?” Kyle asks. “I’d lay down my life for my country.”

“Why?”

“Because it’s the greatest country on earth and I’d do everything I can to protect it,” he says.

She drinks too much. She vomits. He is gallant. He helps her home. They fall in love. Taya is later shown watching television. She yells to Chris in the next room.

“Oh, my God, Chris,” she says.

“What’s wrong?” he asks.

“No!” she yells.

Then we hear the television announcer: “You see the first plane coming in at what looks like the east side. …”

Chris and Taya watch in horror. Ominous music fills the movie’s soundtrack. The evildoers have asked for it. Kyle will go to Iraq to extract vengeance. He will go to fight in a country that had nothing to do with 9/11, a country that columnist Thomas Friedman once said we attacked “because we could.” The historical record and the reality of the Middle East don’t matter. Muslims are Muslims. And Muslims are evildoers or, as Kyle calls them, “savages.” Evildoers have to be eradicated.

Chris and Taya marry. He wears his gold Navy SEAL trident on the white shirt under his tuxedo at the wedding. His SEAL comrades are at the ceremony.

“Just got the call, boys—it’s on,” an officer says at the wedding reception.

The Navy SEALs cheer. They drink. And then we switch to Fallujah. It is Tour One. Kyle, now a sniper, is told Fallujah is “the new Wild West.” This may be the only accurate analogy in the film, given the genocide we carried out against Native Americans. He hears about an enemy sniper who can do “head shots from 500 yards out. They call him Mustafa. He was in the Olympics.”

Kyle’s first kill is a boy who is handed an anti-tank grenade by a young woman in a black chador. The woman, who expresses no emotion over the boy’s death, picks up the grenade after the boy is shot and moves toward U.S. Marines on patrol. Kyle kills her too. And here we have the template for the film and Kyle’s best-selling autobiography, “American Sniper.” Mothers and sisters in Iraq don’t love their sons or their brothers. Iraqi women breed to make little suicide bombers. Children are miniature Osama bin Ladens. Not one of the Muslim evildoers can be trusted—man, woman or child. They are beasts. They are shown in the film identifying U.S. positions to insurgents on their cellphones, hiding weapons under trapdoors in their floors, planting improvised explosive devices in roads or strapping explosives onto themselves in order to be suicide bombers. They are devoid of human qualities.

“There was a kid who barely had any hair on his balls,” Kyle says nonchalantly after shooting the child and the woman. He is resting on his cot with a big Texas flag behind him on the wall. “Mother gives him a grenade, sends him out there to kill Marines.”

Enter The Butcher—a fictional Iraqi character created for the film. Here we get the most evil of the evildoers. He is dressed in a long black leather jacket and dispatches his victims with an electric drill. He mutilates children—we see an arm he cut from a child. A local sheik offers to betray The Butcher for $100,000. The Butcher kills the sheik. He murders the sheik’s small son in front of his mother with his electric drill. The Butcher shouts: “You talk to them, you die with them.”

Kyle moves on to Tour Two after time at home with Taya, whose chief role in the film is to complain through tears and expletives about her husband being away. Kyle says before he leaves: “They’re savages. Babe, they’re fuckin’ savages.”

He and his fellow platoon members spray-paint the white skull of the Punisher from Marvel Comics on their vehicles, body armor, weapons and helmets. The motto they paint in a circle around the skull reads: “Despite what your momma told you … violence does solve problems.”

“And we spray-painted it on every building and walls we could,” Kyle wrote in his memoir, “American Sniper.” “We wanted people to know, we’re here and we want to fuck with you. …You see us? We’re the people kicking your ass. Fear us because we will kill you, motherfucker.”

The book is even more disturbing than the film. In the film Kyle (thanks to Eastwood’s clichéd massaging of the material to make it more seductive to the unbeknowing audience—Eds) is a reluctant warrior, one forced to do his duty. In the book he relishes killing and war. He is consumed by hatred of all Iraqis. He is intoxicated by violence. He is credited with 160 confirmed kills, but he notes that to be confirmed a kill had to be witnessed, “so if I shot someone in the stomach and he managed to crawl around where we couldn’t see him before he bled out he didn’t count.”

Kyle insisted that every person he shot deserved to die. His inability to be self-reflective allowed him to deny the fact that during the U.S. occupation many, many innocent Iraqis were killed, including some shot by snipers. Snipers are used primarily to sow terror and fear among enemy combatants. And in his denial of reality, something former slaveholders and former Nazis perfected to an art after overseeing their own atrocities, Kyle was able to cling to childish myth rather than examine the darkness of his own soul and his contribution to the war crimes we carried out in Iraq. He justified his killing with a cloying sentimentality about his family, his Christian faith, his fellow SEALs and his nation. But sentimentality is not love. It is not empathy. It is, at its core, about self-pity and self-adulation. That the film, like the book, swings between cruelty and sentimentality is not accidental.

“Sentimentality, the ostentatious parading of excessive and spurious emotion, is the mark of dishonesty, the inability to feel,” James Baldwin reminded us. “The wet eyes of the sentimentalist betray his aversion to experience, his fear of life, his arid heart; and it is always, therefore, the signal of secret and violent inhumanity, the mask of cruelty.”

(Editors comment: The above pretty much sums up Eastwood’s style as a director.)

“Savage, despicable evil,” Kyle wrote of those he was killing from rooftops and windows. “That’s what we were fighting in Iraq. That’s why a lot of people, myself included, called the enemy ‘savages.’… I only wish I had killed more.” At another point he writes: “I loved killing bad guys. … I loved what I did. I still do … it was fun. I had the time of my life being a SEAL.” He labels Iraqis “fanatics” and writes “they hated us because we weren’t Muslims.” He claims “the fanatics we fought valued nothing but their twisted interpretation of religion.”

“I never once fought for the Iraqis,” he wrote of our Iraqi allies. “I could give a flying fuck about them.”

He killed an Iraqi teenager he claimed was an insurgent. He watched as the boy’s mother found his body, tore her clothes and wept. He was unmoved.

He wrote: “If you loved them [the sons], you should have kept them away from the war. You should have kept them from joining the insurgency. You let them try and kill us—what did you think would happen to them?”

“People back home [in the U.S.], people who haven’t been in war, at least not that war, sometimes don’t seem to understand how the troops in Iraq acted,” he went on. “They’re surprised—shocked—to discover we often joked about death, about things we saw.”

He was investigated by the Army for killing an unarmed civilian. According to his memoir, Kyle, who viewed all Iraqis as the enemy, told an Army colonel: “I don’t shoot people with Korans. I’d like to, but I don’t.” The investigation went nowhere.

Kyle was given the nickname “Legend.” He got a tattoo of a Crusader cross on his arm. “I wanted everyone to know I was a Christian. I had it put in red, for blood. I hated the damn savages I’d been fighting,” he wrote. “I always will.” Following a day of sniping, after killing perhaps as many as six people, he would go back to his barracks to spent his time smoking Cuban Romeo y Julieta No. 3 cigars and “playing video games, watching porn and working out.” On leave, something omitted in the movie, he was frequently arrested for drunken bar fights. He dismissed politicians, hated the press and disdained superior officers, exalting only the comradeship of warriors. His memoir glorifies white, “Christian” supremacy and war. It is an angry tirade directed against anyone who questions the military’s elite, professional killers.

“For some reason, a lot of people back home—not all people—didn’t accept that we were at war,” he wrote. “They didn’t accept that war means death, violent death, most times. A lot of people, not just politicians, wanted to impose ridiculous fantasies on us, hold us to some standard of behavior that no human being could maintain.”

The enemy sniper Mustafa, portrayed in the film as if he was a serial killer, fatally wounds Kyle’s comrade Ryan “Biggles” Job. In the movie Kyle returns to Iraq—his fourth tour—to extract revenge for Biggles’ death. This final tour, at least in the film, centered on the killing of The Butcher and the enemy sniper, also a fictional character. As it focuses on the dramatic duel between hero Kyle and villain Mustafa the movie becomes ridiculously cartoonish.

Kyle gets Mustafa in his sights and pulls the trigger. The bullet is shown leaving the rifle in slow motion. “Do it for Biggles,” someone says. The enemy sniper’s head turns into a puff of blood.

“Biggles would be proud of you,” a soldier says. “You did it, man.”

His final tour over, Kyle leaves the Navy. As a civilian he struggles with the demons of war and becomes, at least in the film, a model father and husband and works with veterans who were maimed in Iraq and Afghanistan. He trades his combat boots for cowboy boots.

The real-life Kyle, as the film was in production, was shot dead at a shooting range near Dallas on Feb. 2, 2013, along with a friend, Chad Littlefield. A former Marine, Eddie Ray Routh, who had been suffering from PTSD and severe psychological episodes, allegedly killed the two men and then stole Kyle’s pickup truck. Routh will go on trial next month. The film ends with scenes of Kyle’s funeral procession—thousands lined the roads waving flags—and the memorial service at the Dallas Cowboys’ home stadium. It shows fellow SEALs pounding their tridents into the top of his coffin, a custom for fallen comrades. Kyle was shot in the back and the back of his head. Like so many people he dispatched, he never saw his killer when the fatal shots were fired.

The culture of war banishes the capacity for pity. It glorifies self-sacrifice and death. It sees pain, ritual humiliation and violence as part of an initiation into manhood. Brutal hazing, as Kyle noted in his book, was an integral part of becoming a Navy SEAL. New SEALs would be held down and choked by senior members of the platoon until they passed out. The culture of war idealizes only the warrior. It belittles those who do not exhibit the warrior’s “manly” virtues. It places a premium on obedience and loyalty. It punishes those who engage in independent thought and demands total conformity. It elevates cruelty and killing to a virtue. This culture, once it infects wider society, destroys all that makes the heights of human civilization and democracy possible. The capacity for empathy, the cultivation of wisdom and understanding, the tolerance and respect for difference and even love are ruthlessly crushed. The innate barbarity that war and violence breed is justified by a saccharine sentimentality about the nation, the flag and a perverted Christianity that blesses its armed crusaders. This sentimentality, as Baldwin wrote, masks a terrifying numbness. It fosters an unchecked narcissism. Facts and historical truths, when they do not fit into the mythic vision of the nation and the tribe, are discarded. Dissent becomes treason. All opponents are godless and subhuman. “American Sniper” caters to a deep sickness rippling through our society. It holds up the dangerous belief that we can recover our equilibrium and our lost glory by embracing an American fascism.

What is $1 a month to support one of the greatest publications on the Left?

The Secret Life of Hillary Clinton.

John V. Walsh

As a loyal and reliably warmongering member of the imperial establishment, the favorable marketing of Hillary has been a done deal for a long time. (Via M.Mozart, flickr)

CLICK ON IMAGES TO EXPAND

[dropcap]“We’re going in!” [/dropcap] The Envoy’s voice had the sting of a cold wind cutting across the taiga. Ratta. Tatta Tat. The plane out of Ramstein was pelted with a bararage of fire as it descended into Tuzla Air Base in Bosnia. Ratta Tatta Tat. One piece of shrapnel pierced the window next to the Envoy’s seat. She was calm. “We can’t make it ma’am. There’s even heavier fire below.” “That was an order, Major Fenton.” She was even cooler than her voice in the midst of the panic around her. “I’m going up front.”

Hillary as seen by artist DonkeyHotey (via Flickr)

Bursting into the cockpit she took the controls and put the plane into a steep dive, getting it below the barrage of bullets. The plane hit the ground with a fearful bounce, avoiding a crash only because she had become one with the monster jet. On the tarmac, the plane took gunfire again. She cried, “We came here on a mission. We’re going in! Put down the chutes!” The slides deployed. Grabbing a rifle from her bodyguard she was the first one down. Running now, head down, holding rifle aloft with one arm to let the others know the path and with her daughter sheltered under the other, she outpaced them. And then she and the rest were safe in the hanger.

“I felt the snipers’ bullets whizzing overhead,” she declared to the assembled crowd, now safe. The hanger burst into applause. And then she was startled, as from a dream. The applause erupted in the press conference, as she finished her account. The worshipping press was mesmerized by her story. Among those who applauded loudest were those who were with her in Tuzla. They knew it was all a lie. Their careers were flourishing, their salaries soaring. She thanked them all. Before she knew it, she was whisked off the stage.

Hillary speaks on her legal career and on the importance of voting rights at ABA meeting in San Francisco. (8.12.2013) Note the Orwellian motto: “Defending Liberty, Pursuing Justice”, sure to be violated by a corporatist like Clinton. (Via S. Rhodes, flickr)

“Hill, what were you talking about?” Her bewildered husband looked at her in the holding room. You were never fired on, and you don’t even know how to fly a kite let alone a jet. “Oh, shut up, Bill. You underestimate me every time. Your memory fails you. I was there. You forget those long hours of learning to do stunt flying when I was president of the Winged Wellesley Women. For God’s sake don’t quibble about details. I had to push you to expand NATO when your buddies kept harping on Versailles.” Bill looked like a puppy that had just been whacked with a rolled up newspaper. He knew that there had not been so much as a paper plane flown at Wellesley. He bit his lower lip and fell silent.

The limousine picked them up and whisked them away to her all-important speech, her first State of the Union. Bill watched her take the podium before the joint session of Congress.

(Credit: DonkeyHotey, via flickr)

“The Commander in Chief,” the Speaker announced. She looked out over the assemblage. The day was an inferno under an intense sun in Rome, not a cloud in the sky. The Coliseum crowd was going wild, oblivious to the oppressive heat. “Caesar, Caesar, Caesar” the sweltering mass chanted in unison. She was now back from the successful North African campaign to a tumultuous celebration, the likes of which Rome had not seen since the days of the first emperor.

The Speaker came forward and placed a laurel crown on her head. She smiled without showing her teeth and pointed to the ground. The Speaker knelt and she pointed to her feet. He kissed her feet, rose and backed away, bowing as he rededed. She slowly turned 360 degrees looking at each section of the crowd. Then she deliberately raised her hands high. Within a few moments the entire crowd fell silent. Slowly she looked around, very slowly in the deadly silence, paused for what seemed like an eternity, then deliberately, loudly declaimed, “We came….. We saw…. He died.” The assemblage jumped to its feet applauding wildly, insanely. She had echoed the first Caesar, and she had no doubt that her exploits would far outstrip his. She was sure that the Libyan spoils would fill the general coffers. The captured arms were already on the way to Syria for her next campaign. But again the speech was over before she knew it. And again she was in the limousine with Bill. He was distraught. “Hill, you know Gaddafi was killed in a brutal way when you were head at State. It was your idea to do that, and it does not look good when you gloat.” She stared at him scornfully. “Hill,” he said, “I think you are having one of your days again. Maybe Dr. Kleinkopf should adjust your meds again.” “Ridiculous,” she clipped, not even looking his way.

Bill Clinton (DonkeyHotey, via flickr)

They went back to the White House. It was late. Bill went to bed and she went to the White House gym. She got into her white exercise outfit and was ready to do some yoga. And then there he was tight there in the gym, also dressed in white with a black belt and lying in the corner doing some stretches. It was Vlad! How did he get in? She had long suspected that there were breaches of security, and she had grown ever more apprehensive since she had entered the Oval Office. And sure enough there, he was. Before he could make a move, she moved around him, thinking methodically, “Encircle, encircle.” Then she flew at him feet first, striking her soles deeply into his chest and shouting , “Encircle and break.” The blow appeared to knock Vlad unconscious; he was motionless. She touched the inert heap. It was lifeless, cold and wet, the sweat still on the corpse.

But she knew his presence meant that the country was under attack. Grabbing the red wall phone, she called for Bradford. In an instant he was there carrying the black briefcases with the presidential seal on the leather. How she loved those seals and the leather. “Look at that miserable dictator over there,” she yelled at Bradford, here words echoing in the gym. He was befuddled. “That is just a pile of wet towels, Ma’am.” She did not hear him. “We have been attacked,” she cried. “Open the briefcase.” Bradford looked like a truck had run over him – but he was trained for this and did as told. She looked in, her retina was quickly scanned and she turned the two keys. “Done,” she exclaimed triumphantly. “Nobody messes with the Indispensable Nation.” The bays to rocket silos all over the planet were rolling back minutes after she spoke. Bradford was sobbing now.

Sirens were wailing in the White House and throughout the Capital; panic was everywhere. Rockets from across the seas had now been launched and spotted. Bill appeared at the door of the gym. He saw the hysterical Bradford, collapsed on his knees, with the President standing over him, beaming triumphantly but silent. Bill pulled her to the emergency elevator and they plunged into the shelter deep, deep underground. Bill was also sobbing now. But not Hillary; she stood there, erect, adjusting her exercise outfit, with her back against the elevator wall, looking contentedly into the distance, a faint smile on her lips. Again she had prevailed. Hillary Clinton, unbending, defiant to the end.

John V. Walsh can be reached at John.Endwar@gmail.com

What is $1 a month to support one of the greatest publications on the Left?