Studies in decadence: The Rockefeller and the Ballet Boys

From the special archives: Articles you should not have missed.

conspire with the native military and the United States in the defense of their privileges, and to further their common project of systemic exploitation without end.—Guillermo Valdés Ureta

As told on Vanity Fair by the inimitable Dominick Dunne.

____________________________________________

THE MAGAZINE / Originally published on February 1987

DANSE MACABRE

There is no one, not even his severest detractor, and let me tell you at the outset of this tale that he has a great many severe detractors, who will not concede that Raymundo de Larrain, who sometimes uses the questionable title of the Marquis de Larrain, is, or at least was, before he took the road to riches by marrying a Rockefeller heiress nearly forty years his senior, a man of considerable talent, who, if he had persevered in his artistic pursuits, might have made a name for himself on his own merit. Instead his name, long a fixture in the international social columns, is today at the center of the latest in a rash of contested-will controversies in which wildly rich American families go to court to slug it out publicly for millions of dollars left to upstart spouses the same age as or, in this case, younger than the disinherited adult children.

The most interesting person in this story is the late possessor of the now disputed millions, Margaret Strong de Cuevas de Larrain, who died in Madrid on December 2, 1985, at the age of eighty-eight, and the key name to keep in mind is the magical one of Rockefeller. Margaret de Larrain had two children, Elizabeth and John, from her first marriage, to the Marquis George de Cuevas. The children do not know the whereabouts of her remains, or even whether she was, as a member of the family put it, incinerated in Madrid. What they do know is that during the eight years of their octogenarian mother’s marriage to Raymundo de Larrain, her enormous real-estate holdings, which included adjoining town houses in New York, an apartment in Paris, a country house in France, a villa in Tuscany, and a resort home in Palm Beach, were given away or sold, although she had been known throughout her life to hate parting with any of her belongings, even the most insubstantial things. At the time of her second marriage, in 1977, she had assets of approximately $30 million (some estimates go as high as $60 million), including 350,00 shares of Exxon stock in a custodian account at the Chase Manhattan Bank. The location of the Exxon shares is currently unknown, and the documents presented by her widower show that his late wife’s assets amount to only $400,000. Although these sums may seem modest in terms of today’s billion-dollar fortunes, Margaret, at the time of her inheritance, was considered one of the richest women in the world. There are two wills in question: a 1968 will leaving the fortune to the children and a 1980 will leaving it to the widower. In the upcoming court case, the children, who are fifty-eight and fifty-six years old, are charging that the will submitted by de Larrain, who is fifty-two, represents “a massive fraud on an aging, physically ill, trusting lady.”

Although Margaret Strong de Cuevas de Larrain was a reluctant news figure for five decades, the facts of her birth, her fortune, and the kind of men she married denied her the privacy she craved. However, her children, Elizabeth, known as Bessie, and John, have so successfully guarded their privacy, as well as that of their children, that they are practically anonymous in the social world in which they were raised. John de Cuevas, who has been described as almost a hermit, has never used the title of marquis. He is now divorced from his second wife, Sylvia Iolas de Cuevas, the niece of the art dealer Alexander Iolas, who was a friend of his father’s. His only child is a daughter from that marriage, now in her twenties. He maintains homes in St. James, Long Island, and Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he teaches scientific writing at Harvard. Bessie de Cuevas, a sculptor whose work resembles that of Archipenko, lives in New York City and East Hampton, Long Island. She is also divorced, and has one daughter, twenty-two, by her second husband, Joel Carmichael, the editor of Midstream, a Zionist magazine so reactionary that it recently published an article accusing the pope of being soft on Marxism. Friends of Bessie de Cuevas told me that she was never bothered by the short financial reins her mother kept her on, because she did not fall prey to fortune hunters the way her sister heiresses, like Sunny von Bülow, did.

Margaret Strong de Cuevas de Larrain, the twice-titled American heiress, grew up very much like a character in a Henry James novel. In fact, Henry James, as well as William James, visited her father’s villa outside Florence when she was young. Margaret was the only child of Bessie Rockefeller, the eldest of John D. Rockefeller’s five children, and Charles Augustus Strong, a philospher and psychologist, whose father, Augustus Hopkins Strong, a Baptist clergyman and theologian, had been a great friend of old Rockefeller’s. A mark of the brilliance of Margaret’s father was that, while at Harvard, he competed with fellow student George Santayana for a scholarship at a German university and won. He then shared the scholarship with Santayana, who remained his lifelong friend. Margaret was born in New York, but the family moved shortly thereafter to Paris. When Margaret was nine her mother died, and Strong, who never remarried, built his villa in Fiesole, outside Florence. There, in a dour and austere atomosphere, surrounded by intellectuals and philosophers, he raised his daughter and wrote scholarly books. His world provided very little amusement for a child and no frivolity.

Each year Margaret returned to the United States to see her grandfather, with whom she maintained a good relationship, and to visit her Rockefeller cousins. Old John D. was amused by his serious and foreign granddaughter, who spoke several languages and went to school in England. Later, she was one of only three women attending Cambridge University, where she studied chemistry. Never, even as a young girl, could she have been considered attractive. She was big, bulky, and shy, and until the age of twenty-right she always wore variations of the same modest sailor dress.

Her father was eager for her to marry, and toward that end Margaret went to Paris to live, although she had few prospects in sight. Following the Russian Revolution there was an influx of Russian émigrés into Paris, and Margaret Strong developed a fascination for them that remained with her all her life. She was most excited to meet the tall and elegant Prince Felix Yusupov, the assassin of Rasputin, who was said to have used his beautiful wife, Princess Irina, as a lure to attract the womanizing Rasputin to his palace on the night of the murder. In Paris, Prince Yusupov had taken to wearing pink rouge and green eye shadow, and he supported himself by heading up a house of couture called Irfé, a combination of the first syllables of his and his wife’s names. Into this hothouse of fashion, one day in 1927, walked the thirty-year-old prim, studious, and unfashionable Rockefeller heiress. At that time Prince Yusupov had working for him an epicene and penniless young Chilean named George de Cuevas, who was, according to friends who remember him from that period, “extremely amusing and lively.” He spoke with a strong Spanish accent and expressed himself in a wildly camp manner hitherto totally unknown to the sheltered young lady. The story goes that at first Margaret mistook George de Cuevas for the prince. “What do you do at the couture?” she asked. “I’m the saleslady,” he replied. The plain, timid heiress was enchanted with him, and promptly fell in love, thereby establishing what would be a lifelong predilection for flamboyant, effete men. The improbable pair were married in 1928.

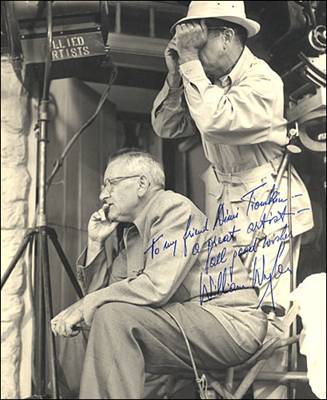

Celebrity fotog Raymundo Larraín with social sponsor Jacqueline de Ribes in another iconic pose (1961, Avedon). Tout pour les arts, mes amis…

From then on Margaret abandoned almost all intellectual activity. She stepped out of the pages of a Henry James novel into the pages of a Ronald Firbank novel. If her father had been the dominant figure of her maidenhood, George de Cuevas was the controlling force of her adult existence. Their life became more and more frivolous, capricious, and eccentric. Through her husband she discovered an exotic new world that centered on the arts, especially the ballet, for which George had a deep and abiding passion. Their beautiful apartment on the Quai Voltaire, filled with pets and bibelots and opulent furnishings, became a gathering place for the haute bohème of Paris, as did their country house in St.-Germain-en-Laye, where their daughter, Bessie, was born in 1929. Their son, John, was born two years later. Along the way the title of marquis was granted by, or purchased from, the King of Spain. The Chilean son of a Spanish father, George de Cuevas is listed in some dance manuals as the eighth Marquis de Piedrablanca de Guana de Cuevas, but the wife of a Spanish grandee, who wished not to be identified, told me that the title was laughed at in Spain. Nonetheless, the Marquis and Marquesa de Cuevas remained a highly visible couple on the international and artistic scenes for the next thirty years.

When World War II broke out, they moved to the United States. Margaret, already a collector of real estate, began to add to her holdings. She bought a town house on East Sixty-eighth Street in New York, a mansion in Palm Beach, and a weekend place in Bernardsville, New Jersey. She also acquired a house in Riverdale, New York, which they never lived in but visited, and one in New Mexico to be used in the event the United States was invaded. In New York, Margaret always kept a rented limousine, and sometimes two, all day every day in front of her house in case she wanted to go out.

Although Margaret had inherited a vast fortune, she was to inherit a vaster one through the persistence of her husband. George de Cuevas’s wooing of his wife’s grandfather, old John D. Rockefeller, turned Margaret from a rich woman into a very rich woman. While John D. had bestowed liberal inheritances on his four daughters during their lifetimes, he believed in primogeniture, and in his late seventies he turned over the bulk of his $500 million fortune to his only son, John D. Rockefeller Jr., the father of Abby, John D. III, Nelson, Laurance, Winthrop, and David. He retained the income for himself. Margaret at that time was indifferent to her inheritance, but George, for whom the prospect of Rockefeller millions had surely been a lure in his choice of a life mate, was not one to sit back and watch what he felt should be his wife’s share pass on to her already very rich Rockefeller cousins. He set about to charm his grandfather-in-law, and charm him he did. He even became his golfing companion. Rockefeller had never come across such a person as this eccentric bird of paradise that his granddaughter had married. Surprisingly, he not only was amused by him but genuinely liked him. The family legend goes that one day George took Bessie and John by the hand to see the old man and said, “Do you want to see your great-grandchildren starve because their mother has not been taken care of the way the rest of the Rockefellers have been?” The tycoon calmly assured him that Margaret would be provided for. Old John D. then began investing his enormous income in the stock market and in the last years of his life made a second fortune, the bulk of which he left to Margaret on his death, when she was forty years old.

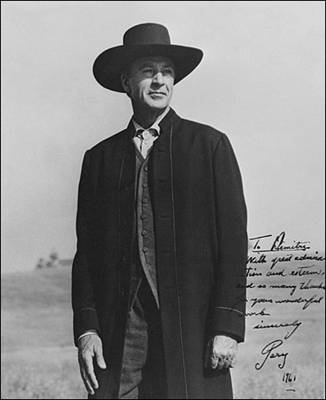

In 1940, in Toms River, New Jersey, George de Cuevas became an American citizen and renounced his Spanish title, claiming he would henceforth be known merely as George de Cuevas. However, he continued to be referred to by his title, and once his role as a ballet impresario grew to international prominence, he changed the name of the company associated with him throughout his career from the Ballet de Monte Carlo to the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas. From 1947 to 1960 the marquis toured the company all over the world, with the financial support of his wife, who donated 15 percent of her income to his troupe. He introduced American dancers to France and French dancers to America, and soon became a beloved figure in the dance world. The impresario Sol Hurok in his biography described him as “a colorful gentleman of taste and culture … perhaps the outstanding example we have today of the sincere and talented amateur in and patron of the arts.”

Actually, de Cuevas is better remembered for one episode of histrionics and temperament than for any of his productions. In 1958 the dancer and choreographer Serge Lifar, then fifty-two years old, became angry when the marquis’s company changed the choreography of his balletBlack and White. After a heated exchange of words the marquis, who was seventy-two at the time, slapped Lifar in the face with a handkerchief in public and then refused to apologize. Lifar challenged de Cuevas to a duel, and the marquis accepted. Although neither of the combatants was known as a swordsman, épées were chosen as the weapons. The location of the duel was to be kept secret because dueling was outlawed in France, but more than fifty tipped-off reporters and photographers showed up at the scene. The encounter was scheduled to last until blood was drawn. For the first four minutes of the duel Serge Lifar leapt about while the marquis remained stationary. In the third round the marquis forced Lifar back by simply advancing with his sword held straight in front of him, and pinked his opponent. It was not clear, according to newspaper accounts of the duel, whether skill or accident brought the maraquis’s blade into contact with Lifar’s arm. “Blood has flowed! Honor is saved!” cried Lifar. Both men burst into tears and rushed to embrace each other. Reporting the event on its front page, the New York Times said that the affair “might well have been the most delicate encounter in the history of French dueling.”

As a couple, the Marqius and Marquesa de Cuevas became increasingly eccentric. “It was unconventional, their marriage, but, curiously, it worked,” said the Viscountess Jacqueline de Ribes, who was a frequent guest in their Paris apartment. “There were always people waiting in the hall to have an audience—it was like a court,” said one family member. Another longtime observer of the inner workings of the de Cuevas household, Jean Pierre Lacloche, said, “Margaret was always in her room during the parties. She hated coming out, but usually finally did. She gave in to all of George’s pranks. She didn’t care. He made life interesting around her.” George de Cuevas often received visitors lying in bed wearing a black velvet robe with a sable collar and surrounded by his nine or ten Pekingese dogs, while Margaret grew more and more reclusive and slovenly in her dress. She always wore black and kept an in-residence dressmaker to make the same dress for her over and over again. When she traveled to Europe, she would book passage on as many as six ships and then be unable to make up her mind as to which day she wanted to sail. If she wanted to go from Palm Beach to New York, she would book seats on every train for a week, and then not be able to make the commitment to move. Once, unable to secure a last-minute booking on a Paris-Biarritz train and determined to leave, no matter what, she piled her daughter, maid, ten Pekingese dogs, and her luggage into a Paris taxicab and had the driver drive her the five hundred miles to Biarritz. The trip took three days.

George De Cuevas liked to entertain, and he filled their homes with society figures, titles, celebrated artists and dancers, and constant flow of Russian émigrés. “At the Cuevas parties were such as the Queen Mother of Egypt, Maria Callas, and of course, Salvador Dali, who was a regular in the house,” said Mafalada Davis, an Egyptian-born public-relations woman who was a great friend of George de Cueva’s. George was a giver of gifts. He bought old furs and jewels from the poor Russians in Paris and gave them away as presents. He gave the Viscountess de Ribes a sable coat, and he gave Mrs. Gurney Munn of Palm Beach a watch on which he had engraved “May the ticking of this watch remind you of the beauty of your faithful heart.”

Somehow, in the midst of this affluent chaos on two continents, Bessie and John de Cuevas were raised. A relative of the family told me that Margaret had a good strong relationship with her children. “Not a peasant-type relationship,” he said, “not conventional,” meaning, as I understood him, not many hugs and kisses, but strong in its way. Another relative said, “After a short period with her children—and later with her grandchildren—she was ready to send them out to play or to turn them over to their nanny.” Margaret, who throughout her life was notorious for never being on time, arrived so late for her daughter’s coming-out party at the Plaza hotel in New York, which was attended by all of her Rockefeller relations, that she almost missed it. When Bessie was seventeen she met Hubert Faure, who became her first husband. “She was an extraordinary-looking person,” said Faure about his former wife, with whom he has retained a close friendship. “English-American in intellect with a Spanish vitality behind that.” Hubert Faure, now the chairman of United Technology, was not at the time considered much of a catch by the Marquis de Cuevas, who wanted his daughter to marry a Spanish grandee and possess a great title. But Bessie exhibited a early independence: she went ahead and married Faure in Paris when she was nineteen, with no family and only another couple in attendence. John, her brother, was also married for the first time at an early age. The children, as Bessie and John are regularly referred to in the upcoming court case with Raymundo de Larrain, have at times shown a bemused attitude about their life. Once, when questioned about her nationality, Bessie described herself as a third-generation expatriate. John, during a brief Wall Street career, was asked by a colleague if he could possibly be related to a mad marquesa of the same name. “Yes,” he is said to have replied, “she is a very distant mother.”

The apex of the social career of George de Cuevas was reached in 1953 with a masked ball he gave in Biarritz; it vied with the Venetian masked ball given by Carlos de Beistegui in 1951 as the most elaborate fête of the decade. France at the time was paralyzed by general strike. No planes or trains were running. Undaunted, the international nomads, with their couturier-designed eighteenth-century costumes tucked into their steamer trunks, made their way across Europe like migrating birds to participate in thetableaux vivants at the Marquis de Cuevas’s ball, an event so extravagant that it was criticized by both the Vatican and the left wing. “People talked about it for months before,” remembered Josephine Hartford Bryce, the A&P heiress who recently donated her costume from that ball to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Everyone was dying to go to it. The costumes were fantastic, and people spent most of the evening just staring at each other.” As they say in those circles, “everyone” came. Elsa Maxwell dressed as a man. The Duchess of Argyll, on the arm of the duke, who would later divorce her in messiest divorce in the history of British society, came dressed as an angel. Ann Woodward, of the New York Woodwards, slapped a woman she thought was dancing too often with her husband, William, whom she was to shoot and kill two years later. King Peter of Yugoslavia waltzed with a diamond-tiara’d Merle Oberon. And at the center of it all was the Marquis George de Cuevas, in gold lamé with a headdress of grapes and towering ostrich plumes, who presided as the King of Nature. He was surrounded by the Four Seasons, in the costumed persons of the Count Charles de Ganay, Princess Marella Caracciolo, who would soon become the wife of Fiat king Gianni Agnelli, Bessie, his daughter, and her then husband, Hubert Faure. As always, Margaret de Cuevas did the unexpected. For days beforehand, her costume designed by the great couturier Pierre Balmain, who had paid her the honor of coming to her for fittings, hung, like a presence, on a dress dummy in the hallway of the de Cuevas residence in Biarritz. But Margaret did not appear at the ball, although, of course, she paid for it. She may have been an unlikely Rockefeller, but she was still a Rockefeller, and the opulence, extravagence, and sheer size (four thousand people were asked and two thousand accepted) of the event offended her. She simply disappeared that night, and the party went on without her. She did, however, watch the arrival of the guests from a hidden location, and a much repeated, but unconfirmed, story is that she sent her maid to the ball dressed in her Balmain costume.

George de Cuevas increasingly made his life and many homes available to a series of young male worldings who enjoyed the company of older men. In the early 1950s Margaret de Cuevas purchased the town house adjoining hers on East Sixty-eighth Street in New York. The confirmation-of-sale letter from the realty firm of Douglas L. Elliman & Co. contained a cautionary line: “The Marquesa detests publicity and would appreciate it if her name weren’t divulged.” An unkind novel by Theodore Keogh, called The Double Door, depicted the marriage of George and Margaret and their teenage daughter. The double door of the title referred to that point of access between the two adjoining houses, beyond which the wife of the main character, a flamboyant nobleman, was not permitted to go, although the houses were hers. The drama of the novel revolved around the teenage daughter’s clandestine romance with one of the handsome young men beyond the double door. Inevitably, the marriage of George and Margaret de Cuevas began to founder, and for the most part they occupied their various residences at different times. They maintained close communication, however, and Margaret would often call George in Paris or Cannes from New York or Palm Beach to deal with a domestic problem. Once when the marquesa’s temperamental chef in Palm Beach became enraged at one of her unreasonable demands and threw her breakfast tray at her, she called her husband in Paris and asked him to call the chef and beseech him not only not to quit but also to bring her another breakfast, because she was hungry. George finally persuaded the chef to recook the breakfast, but the man refused to carry it to Margaret. A maid in the house had to do that.

At this point in the story, Raymundo de Larrain entered the picture. “Raymundo is not just a little Chilean,” said a lady of fashion in Paris about him. “He is from one of the four greatest families in Chile. The Larrains are aristocratic people, a better family by far than the de Cuevas family.” Whatever he was, Raymundo de Larrain wanted to be something more than just another bachelor from Chile seeking extra-man status in Paris society. He was talented, brilliant, and wildly extravagant, and soon began making a name for himself designing costumes and sets for George de Cuevas’s ballet company. A protégé of the marquis’s to start with, he soon became known as his nephew. An acquaintance who knew de Larrain at the time recalled that the card on the door of his sublet apartment first read M. Larrain. Later it became M. de Larrain. Later still it became the Marquis de Larrain.

In Bessie de Cuevas’s affidavit in the upcoming probate proceedings, she emphatically states that although various newspapers have described de Larrain as the nephew of her father and suggested that he was raised by her parents, there was no blood relation between the two men. In a letter to an American friend in Paris, she wrote, “He is not my father’s nephew. I think he planted the word long ago in Suzy’s column. If there is any relationship at all, it is so remote as to be meaningless.” Yet as recently as November, when I spoke with de Larrain in Palm Beach, he referred to George de Cuevas as “my uncle.” The fact of the matter is that Raymundo de Larrain has been described as a de Cuevas nephew and has been using the title of marquis for years, and he was on a familiar basis with all members of the de Cuevas family. Longtime acquaintances in Paris remember Raymundo calling Margaret de Cuevas Tante Margaret or, sometimes, perhaps in levity, Tante Rockefeller. In her book The Case of Salvador Dali, Fleur Cowles described the Dali set in Paris as follows: “On May 9th, 1957, the young nephew of the Marquis de Cuevas gave a ball in honour of the Dalis. According to Maggi Nolan, the social editor of the Paris Herald-Tribune, the Marquis Raymundo de Larrain’s ball was ‘unforgettable’ in the apartment which has been converted … into a vast party confection,” with “the most fabulous gala-attired members of international society.” Fleur Cowles then went on to list the guests, including in their number the Marquis de Cuevas himself, without his wife, and M. and Mme. Hubert Faure, his daughter and son-in-law. Although Cowles did not say so, George de Cuevas almost certainly paid for Raymundo’s ball.

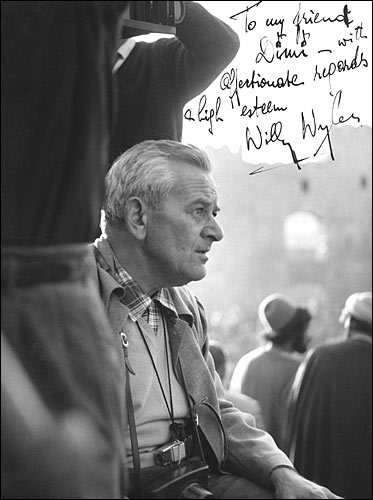

Along the way de Larrain met the Viscountess Jacqueline de Ribes, one of the grandest ladies in Paris society and a ballet enthusiast to boot. “Before Jacqueline, no one had ever heard of Raymundo de Larrain except as a nephew of de Cuevas. Jacqueline was his stepping-stone into society,” said another lady of international social fame who did not wish to be identified. The viscountess became an early admirer of his talent, and they entered into a close relationship that was to continue for years, sharing an interest in clothes and fashion as well as the ballet. Raymundo de Larrain is said to have made Jacqueline de Ribes over and given her the look that has remained her trademark for several decades. A famous photograph taken by Richard Avedon in 1961 shows the two of them in exotic matching profiles. At a charity party in New York known as the Embassy Hall, chaired by the Viscountess de Ribes, Mrs. Winston Guest, and the American-born Princess d’Arenberg, Raymundo de Larrain’s fantastical butterfly décor was so extravagant that there was no money left for the charity that was meant to benefit from the event. In time the viscountess became known as the godmother of the ballet, and she, more than any other person, pushed the career of Raymundo de Larrain.

After the publication of The Double Door, the de Cuevases were often the subject of gossip in the sophisticated society in which they moved, but somehow they had the ability to keep scandal within the family perimeter. The relationship of both husband and wife with the unsavory Jan de Vroom, however, almost caused their peculiar habits to be open to public scrutiny. A family member said to me that at this point in Margaret de Cuevas’s life she fell into a nest of vipers. Born in Dutch Indonesia, Jan de Vroom was a tall, blond adventurer who dominated drawing rooms by sheer force of personality rather than good looks. A wit, a storyteller, and a linguist, he had an eye for the main chance, and like a great many young men before him looking for the easy ride, he attached himself to George de Cuevas. De Vroom was quick to realize on which side the bread was buttered in the de Cuevas household, and, to the distress of the marquis, who soon grew to distrust him, he shifted his attentions to Margaret, whom he followed to the United States. At first Margaret was not disposed to like him, but, undeterred by her initial snubs, he schooled himself in Mozart, whom he knew to be her favorite composer, and soon found favor with her as a fellow Mozart addict. He got a small apartment in a brownstone a few blocks from Margaret’s houses on East Sixty-eighth Street and was always available when she needed a companion for dinner. She set him up in business, as an importer of Italian glass and lamps. From Europe, George de Cuevas tried to break up the deepening intimacy, but Margaret, egged on by her friend Florence Gould, ignored her husband’s protests. As the friendship grew, so did de Vroom’s store of acquisitions. He was a sportsman, and through Margaret de Cuevas’s bounty he soon owned a sleek sailing boat, a fleet of Ferrari cars, a Rolls Royce, and—briefly, until it crashed—an airplane. He also acquired an important collection of rare watches.

Raymundo de Larrain and Jan de Vroom detested each other, and Jan, in the years when he was in favor with Margaret, refused to have Raymundo around. De Vroom had no wish to join the ranks of men who made their fortune at the altar; he was content to play the role of son to Margaret, a sort of naughty-boy son whose peccadilloes she easily forgave. A mixer in the darker worlds of New York and Florida, he entertained her with stories of his subterranean adventures. Often, in her own homes, she would be the only woman present at a dining table full of men who were disinterested in women.

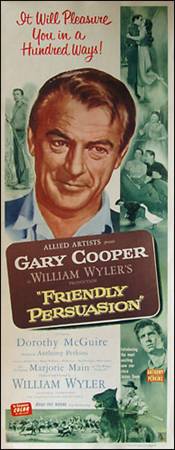

In 1960 the Marquis de Cuevas, in failing health, offered Raymundo de Larrain, with whom he was now on the closest terms, the chance to create a whole new production of The Sleeping Beauty, to be performed at the Théâtre de Champs-Élysées. De Larrain’s Sleeping Beauty is still remembered as one of the most beautiful ballet productions of all time, and it was the greatest box-office success the company had ever experienced. The marquis was permitted by his physicians to attend the premiere. “If I am going to die, I will die backstage,” he said. After the performance he was pushed out onto the stage in a wheelchair and received a standing ovation. George de Cuevas attended every performance up until two weeks before his death. He died at his favorite of the many de Cuevas homes, Les Délices, in Cannes, on February 22, 1961. Margaret, who was in New York, did not visit her husband of thirty-three years in the months of his decline. In his will George left the house in Cannes to his Argentinean secretary, Horacio Guerrico, but Margaret was displeased with her husband’s bequest and managed to get the house back from the secretary in exchange for money and several objects of value.

Although Margaret had never truly shared her husband’s passion for the ballet, or for the ballet company bearing his name, which she had financed for so many years, she did not immediately disband it after his death. Instead she appointed Raymundo de Larrain the new head of the company. There was always a sense of dilettantism about George de Cuevas’s role as a Maecenas of the dance—not dissimilar to the role Rebekah Harkness would later play with her ballet company. The taste and caprices of the marquis determined the policy of the company, which relied on the box-office appeal of big-star names. This same sense of dilettantism carried over into de Larrain’s contribution. The de Cuevas company has been described to me by one balletomane as ballet for people who normally despise ballet, ballet for society audiences, as opposed to dance audiences.

De Larrain’s stewardship of the company was brief but not undramatic. In June 1961 he played a significant role in the political defection of Rudolf Nureyev at the Paris airport when the Kirov Ballet of Leningrad was leaving France. The story has become romanticized over the years, and everyone’s version of it differs. According to de Larrain, Nureyev had confessed to Clara Saint, a half-Chilean, half-Argentinean friend of de Larrain’s, that he would rather commit suicide than go back to Russia. In one account, Clara Saint, feigning undying love for the departing star, screamed out to Nureyev that she must have one more kiss from him before he boarded the plane and returned to his homeland. Nureyev went back to kiss her, jumped over the barriers, and escaped in a waiting car as the plane carrying the company took off. De Larrain says that Clara Saint had alerted the French authorities that there was going to be a defection, and she advised Nureyev during a farewell drink at the airport bar that he must ask the French police at the departure gate for political asylum. He says that Nureyev spat in the face of the Russian security official. For a while Nureyev lived in de Larrain’s Paris apartment, and the first time he danced after his defection was for the de Cuevas company, in de Larrain’s production of The Sleeping Beauty. “He danced like a god, but he also had a spectacular story,” de Larrain told me. At one of his first performances the balcony was filled with Communists, who pelted the stage with tomatoes and almost caused a riot. People who were present that night remember that Nureyev continued to dance through the barrage, as if he were unaware of the commotion, until the performance was finally halted.

In Raymundo de Larrain’s affidavit for the probate, he assesses his role in Nureyev’s career in an I’m-not-nobody tone: “With the help of Margaret de Cuevas we made him into one of the biggest stars in the history of ballet.” The professional association between de Larrain and Nureyev, which might have saved the de Cuevas ballet, did not last, just as most of de Larrain’s professional associations did not last. “Raymundo and Rudolf did not have the same point of view on beauty and the theater, and they fought,” explained the Viscountess de Ribes in Paris recently. “Raymundo had great talent and tremendous imagination. He had the talent to be a stage director, but neither the health nor the courage to fight. He was very unrealistic. He didn’t know how to talk to people. He was too grand. What Raymundo is is a total aesthete, not an intellectual. He wanted to live around beautiful things. He was very generous and gave beautiful presents. Even the smallest gift he ever gave me was perfect, absolutely perfect,” she said. Another friend of de Larrain’s said, “Raymundo had more taste and knowledge of dancing than anyone. His problem was that he was unprofessional. He couldn’t get along with people. He had no discipline over himself.” When the Marquesa de Cuevas decided in 1962 not to underwrite the ballet company any longer, it was disbanded. Then, under the sponsorship of the Viscountess de Ribes, de Larrain formed his own ballet company. He began by producing and directingCinderella, in which he featured Geraldine Chaplin in a modest but much publicized role. The Viscountess, however, couldn’t afford for long to underwrite a ballet company, and withdrew after two years. Raymundo de Larrain then took to photographing celebrities for Vogue, Town & Country, and Life. His friends say that he had one obsession: to “make it” in the eyes of his family back in Chile. He mailed every newspaper clipping about himself to his mother, for whom, de Ribes says, “he had a passion.”

For years Margaret de Cuevas’s physical appearance had been deteriorating. Never the slightest bit interested in fashion or style, she began to assume the look of what has been described to me by some as a millionairess bag lady and by others as the Madwoman of Chaillot. “Before Fellini she was Fellini,” said Count Vega del Ren about her, but other assessments were less romantic. Her nails were uncared for. Her teeth were in a deplorable state. She had knee problems that gave her difficulty in walking. She covered her face with a white paste and white powder, and she blackened her eyes in an eccentric way that made people think she had put her thumb and fingers in a full ashtray and rubbed them around her eyes. Her hair was dyed black with reddish tinges, and around her head she always wore a black net scarf, which she tied beneath her chin. She wrapped handkerchiefs and ribbons around her wrists to hide her diamonds, and her black dresses were frequently stained with food and spilled white powder and held together with safety pins. For shoes she wore either sneakers or a pair of pink polyester bedroom slippers, which were very often on the wrong feet. Her lateness had reached a point where dinner guests would sit for several hours waiting for her to make an appearance, while Marcel, her butler of forty-five years, would pass them five or six times, carrying a martini on a silver tray to the marquesa’s room. “She drank much too much for an old lady,” one of her frequent guests told me. Finally her arrival for dinner would be heralded by the barking of her Pekingese dogs, and she would enter the dining room preceded by her favorite of them, Happy, who had a twisted neck and a glass eye and walked with a limp as the result of a stroke.

Her behavior also was increasingly eccentric. In her bedroom she had ten radios sitting on tables and chests of drawers. Each radio was set to a different music station—country-and-western, rock ’n’ roll, classical—and when she wanted to hear music she would ring for Marcel and point to the radio she wished him to turn on. For years she paid for rooms at the Westbury Hotel for a group of White Russians she had taken under her wing.

In the meantime Jan de Vroom had grown increasingly alcoholic and pill-dependant. “If someone’s eyes are dilated, does that mean they’re taking drugs?” Margaret asked a friend of de Vroom’s. “I’ve been too kind to him. I’ve spoiled him.” Young men—mostly hustlers and drug dealers—paraded in and out of his apartment at all hours of the day and night. In 1973 two hustlers, whom he knew, rang the bell of his New York apartment. On a previous visit they had asked him for a loan of $2,000, and he had refused. When de Vroom answered the bell, they sent up a thug to frighten him and demand money again. Jan de Vroom, in keeping with his character, aggravated the thug and incited him to rage. A French houseguest found his body: his throat had been cut, and he had been stabbed over and over again. Although he was known to be the person closest to Margaret de Cuevas at that time in her life, her name was not brought into any of the lurid accounts of his murder in the tabloid papers. De Vroom’s body, covered from the chin down to conceal his slit throat, lay in an open casket in the Westbury Room of the Frank E. Campbell Funeral Chapel at Madison Avenue and Eighty-first Street. Except for a few of the curious, there were no visitors. A little-known fact of the sordid situation was that, through the intercession of Margaret de Cuevas, the body was laid to rest in the Rockefeller cemetery in Pocantico Hills, the family estate, although subsequently it was shipped to Holland. The killers were caught and tried. There was no public outcry over the unsavory killing, and they received brief sentences. It is said that one of them still frequents the bars in New York.

Into this void in the life of the Marquesa Margaret de Cuevas moved Raymundo de Larrain. People meeting Margaret de Cuevas for the first time at this point were inclined to think that the cultivated lady was not intelligent, because she was unable to converse in the way people in society converse, and they suspected that she might be combining sedatives and drink. The same people are uniform in their praise of Raymundo de Larrain during this time. For parties at her house in New York, Raymundo would invite the guests and order the food and arrange the flowers, in much the same way that her late husband had during their marriage, and no one would argue the point that Raymundo surrounded her with a better crowd of people than Jan de Vroom ever had. He would choreograph a steady stream of handpicked guests to Margaret’s side during the evening. “ ‘Go and sit with Tante Margaret and talk with her, and I will send someone over in ten minutes to relieve you,’ ” a frequent guest told me he used to say. “He was lovely to her.” Another view of Raymundo at this time came from a New York lady who also visited the house: “He was so talented, Raymundo. Such a sense of fantasy. But he got sidetracked into moneygrubbing.” Whatever the interpretation, Margaret de Cuevas and Raymundo became the Harold and Maude of the Upper East Side and Palm Beach. Bessie de Cuevas, in her affidavit, acknowledges that “Raymundo was always attentive and extremely helpful to my mother, particularly in her social life, which consisted almost exclusively of gatherings and entertainments at her various residences.”

On April 25, 1977, at the oceanfront estate of Mr. and Mrs. Wilson C. Lucom in Palm Beach, the Marquesa Margaret de Cuevas, then eighty years old, married Raymundo de Larrain, then forty-two, in a hastily arranged surprise ceremony. The wedding was such a closely guarded secret that Margaret de Cuevas’s children, Bessie and John, did not know of it until they read about it in Suzy’s column in the New York Daily News. Bessie de Cuevas’s friends say that she felt betrayed by Raymundo because he had not told her of his plans to marry her mother. Among the prominent guests present at the wedding were Rose Kennedy, Mrs. Winston Guest, and Mary Sanford, known as the queen of Palm Beach, who that night gave the newlyweds a wedding reception at her estate. In her affidavit Bessie de Cuevas states, “I had visited with my mother at some length at her home in New York just about two months before. She was clearly aging but we talked along quite well about personal and family things. She said she would be leaving soon to spend some time at her home in Florida. She did not in any way suggest that she was considering getting married. After I read the article, I called her at once in Florida. She could only speak briefly and seemed vague. I assured her that of course my brother John and I wanted anything that would make her comfortable and happy, but why, I asked, did she do it this way. Her reply was simply, ‘It just happened.’ ”

Wilson C. Lucom, the host of the wedding, was also married to an older woman, the since deceased Willys-Overland automobile heiress Virginia Willys. Lucom, who had trained as a lawyer, never practiced law, but had served on the staff of the law secretary of state Edward Stettinius. Shortly after the wedding, in response to an inquiry from the Rockefeller family, he sent a Mailgram to John D. Rockefeller III, the first cousin of Margaret Strong de Cuevas de Larrain, stating his position as the representative of the marquesa and now of de Larrain. “Do not worry about her or be concerned about any rumors you may have heard,” the Mailgram read. “She was married at our house with my wife and myself as witnesses. It was a solemn ceremony, and she was highly competent and knew precisely that she was being married and did so of her own free will being of sound mind.” Bessie de Cuevas says in her affidavit, “I had never met or heard my mother speak of Mr. Lucom.”

For the wedding, Raymundo told friends, he gave his bride a wheelchair and new teeth. He also supervised a transformation of her appearance. “You must understand this: Raymundo cleaned Margaret up. Why, her nails were manicured for the first time in years.” He got rid of the white makeup and blackened eyes, and he supervised her hair, nails, cosmetics, and dress. “Margaret was never better cared for” is a remark made over and over about her after her marriage. De Larrain would invite people to lunch or for drinks and wheel her out to greet her guests; he basked in the compliments paid to his wife on her new appearance. However, lawyers for the Chase Manhattan Bank, which represents Bessie and John de Cuevas’s interests, told me that the two health-care professionals who cared for the marquesa at different times in 1980 and 1982 recalled that de Larrain did not spend much time with his wife, and that she would often ask about him. But when attention was paid by him, it would be lavish; he would send roses in great quantity or do her makeup. Since he had arranged it so that no one would become close to his wife, “she was particularly vulnerable to such displays of charm and affection.” During her second marriage, she became known as Margaret Rockefeller de Larrain. Although this was illustrious-sounding, it was incorrect, for it implied that she was born Margaret Rockefeller rather than Margaret Strong. “The snobbishness and enhancement were de Larrain’s,” sniffed a friend of her daughter’s.

Shortly after the marriage, Sylvia de Cuevas, the then wife of John de Cuevas, took the marquesa’s two granddaughters to visit her in Palm Beach. She says she was stopped at the front door by an armed guard, who would not let them enter until permission was granted by Raymundo. Soon other changes began to take place. Old servants who had been with the marquesa for years, including her favorite, Marcel, were fired by de Larrain. Bessie de Cuevas claims in her affidavit that he accused them of stealing and other misdeeds. Long-term relationships with lawyers and accountants were severed. Copies of correspondence to the marquesa from Richard Weldon, her lawyer for many years, reflect that her directives to them were so unlike her usual method of communication that they questioned the authority of the letters. Shortly thereafter both men were replaced.

Another longtime secretary, Lillian Grappone, told Bessie de Cuevas that her mother had complained of the fact that there were constantly new faces around her. During this period the many houses of the marquesa were sold or given to charity, among them her two houses on East Sixty-eighth Street in New York, which had always been her favorite as well as her principal residence. Bessie de Cuevas claims in her affidavit that her mother sometimes could not recall signing anything to effect the transfer of these houses. At other times she would talk as if she could get them back. On one occasion she acknowledged having signed away the houses but said she had been talked into it at a time when she was not feeling well. Her father’s villa in Fiesole, where she had grown up, was given to Georgetown University. The house in Cannes was given to Bessie and John de Cuevas. Her official residence was moved from New York to Florida, but she was moved out of her house of many years on El Bravo Way in Palm Beach to a condominium on South Ocean Boulevard. Several people who visited her at the condominium said that she seemed confused as to why she should be living there instead of in her own house. Other friends explain the move as a practical one: the house on El Bravo Way was an old Spanish-style one on several floors and many levels, badly in need of repair, and for an invalid in a wheelchair life was simpler in the one-floor apartment.

During this period the financial affairs of the marquesa were handled more and more by Wilson C. Lucom, the host at the wedding. Bessie de Cuevas states in her affidavit, “I think my mother’s belief that Lucom would safeguard her interests against de Larrain only highlights her lack of appreciation for the reality of her circumstances.” Bessie de Cuevas tells of an occasion when she visited her mother at the Palm Beach condominium and Lucom “taunted” her by boasting that he and de Larrain were drinking “Rockefeller champagne.” “My mother’s total dependence on de Larrain is reflected in an explanation she gave for why she did not accompany de Larrain to Paris on a trip he made concerning her holdings there. De Larrain told her no American carrier flew to Paris any longer, and since my mother did not care for Air France, it was best for her not to go. Plainly, my mother had lost any independent touch with the real world.”

Access to her mother became more and more difficult for Bessie de Cuevas. When she called, she was told her mother could not come to the telephone. Some friends who visited the marquesa say that she would complain that she never heard from her daughter. Others say that messages left by Bessie were never given to her. In 1982 Raymundo de Larrain took his wife out of the country, and they began what lawyers representing the de Cuevases’ interests call an “itinerant existence.” She never returned. They went first to Switzerland, then to Chile, where he was from and where they had built a house, and finally to Madrid, where de Larrain was made the cultural attaché at the Chilean Embassy. There Margaret died in a hotel room in 1985. Bessie de Cuevas saw her mother for the last time a few weeks before she died. Neither Bessie nor her brother has any idea where she is buried.

Certainly there was trouble between the Rockefeller family and the newlywed de Larrains from the time of the marriage. After the change of residence from New York to Florida, David Rockefeller urged his cousin to donate her two town houses at 52 and 54 East Sixty-eighth Street to an institution supported by the Rockefeller family called the Center for Inter-American Relations. The appraisal of the two houses was arranged by David Rockefeller, and the appraiser had been in the employ of the Rockefellers for years. He evaluated the two houses at $725,000. Subsequently Margaret de Larrain was distressed to hear that these properties, which she had donated to the Center for Inter-American Relations, were later sold to another favorite Rockefeller forum, the Council on Foreign Relations, for more than twice the amount of money they had been appraised at.

Raymundo de Larrain, in his affidavit for the probate proceedings, says that his wife’s male Rockefeller cousins discriminated against the females of the family. “Not only did her cousin-trustee [John D. Rockefeller III] want to dominate her life and tell her how to spend her trust income, but wanted also to dictate and approve how she spent her non-trust personal principal and income. My wife strongly resented their intrusion in her personal life.… Her position was that her money was hers outright, not part of her trust, and that she and she alone was to decide how she spent it or what gifts she—not they—would make.” Late in the affidavit, de Larrain says that his wife’s trustees “wanted her to give virtually all her personal wealth away to her children long before she even thought of dying. Then they would control her through their control of her trust income.”

De Larrain said that his wife had been generous with her two children, but that they were not satisfied with her gifts of millions to them. “They wanted more and more.” After giving her children more than $7 million, she refused to transfer her personal wealth to them. Even after her gift of $7 million, he claimed, the trustees cut her trust income. “My wife was shocked and distressed at the unjust and cruel and illegal actions of the cousin-trustees in pressuring her to give millions to her children and then breaking their agreement not to cut her trust income. This further alienated her from her family. She felt cheated and a victim of a plan by the family and the Chase Manhattan Bank.”

On February 21,1978, a year after her marriage, Margaret de Larrain, at age eighty-one, revoked all prior wills and codicils executed by her. “I have personally destroyed the original wills in my possession, namely, two original wills dated February 14, 1941, and an original will dated April 26, 1950, and an original will dated May 14, 1956, and an original will dated May 17,1968, and an original will dated June 11, 1968.” Thereafter, Margaret de Larrain added two codicils to a new will of November 20, 1980. In the first, she stated that she had already transferred her fortune to her husband, and she made him the sole beneficiary and sole personal representative of her estate. In the second, she expressed her specific wish that her only two children and two grandchildren receive nothing. De Larrain ended his affidavit with this statement: “There is also abundant testimony that my wife was entirely competent when she later added the two codicils which expressed that she wanted to give the property to me, her husband. She did this because her children neglected her and she had provided abundantly for them in her lifetime by giving them approximately $7 million in gifts.”

It might be added that Margaret’s will did not set a precedent in the stodgy Rockefeller family. Her mother’s sister Edith Rockefeller McCormick, who divorced her husband, Henry Fowler McCormick, heir to the International Harvester fortune, and then engaged in a series of flamboyant affairs with male secretaries which caused her father great embarrassment, in 1932 bequeathed half of her fortune to a Swiss secretary.

Pending the upcoming court case, Raymundo de Larrain has dropped out of public view. When he is in Paris, he lives at the Meurice hotel, but even his closest friends there, including the Viscountess de Ribes, do not hear from him, and he has dropped completely out of the smart social life that he once pursued so vigorously. On encountering Hubert Faure, the first husband of Bessie de Cuevas, in the bar of the Meurice recently, he turned his back on him. In Madrid he stays sometimes at the Palace Hotel and sometimes at less well known ones. He has been seen dining alone in restaurants there. Sometimes he nods to former acquaintances, but he makes no attempt to renew friendships. He has also been seen in Rabat and Lausanne. In the past year he has made two substantial gifts to charity. He gave a check for $500,000 to Georgetown University to supplement the gift of his late wife’s father’s villa in Fiesole to Georgetown. “You have to figure that if Raymundo gave a million dollars to the Spanish Institute before the trial, he must have already squirreled away at least $10 million,” said a dubious Raymundo follower in Paris recently.

This is not a sad story. The deprived will not go hungry. If the courts are able to ascertain what happened to Margaret Strong de Cuevas de Larrain’s fortune in the years of her marriage and to decide on an equitable distribution of her wealth, already rich people will get richer. As a woman friend of Raymundo de Larrain’s said to me recently, “Raymundo will be bad in court, nervous and insecure. If there’s a jury, the jury won’t like him.” She thought a bit and then added, “It’s only going to end up wrong. If you don’t behave correctly, nothing turns out well. I mean, would you like to fight the Rockefellers, darling?”

Dominick Dunne is a best-selling author and special correspondent for Vanity Fair. His diary is a mainstay of the magazine.