From the ARCHIVES—by way of wsws.org:

wsws.org. Penned by David Walsh, of course. —PG

_______

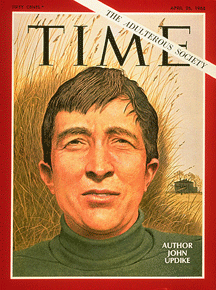

Novelist John Updike dead at 76: Was he a “great novelist”?

By David Walsh | 29 January 2009

American novelist John Updike died January 27 in Danvers, Massachusetts, at the age of 76. The cause of death was cancer.

A major figure in American literature for the past half-century (his first full-length novel, The Poorhouse Fair, appeared in 1959), Updike published more than 60 works—novels, collections of short stories, volumes of essays, art criticism and more.

Many tributes have appeared in the short time since his death, and the writer is certainly worthy of serious consideration. It would be preferable, however, if the commentary were somewhat more thoughtful and sober. Repeated claims along the lines that Updike was “the greatest novelist writing in English,” “one of the greatest American novelists of the 20th century,” “our time’s greatest man of letters” and so forth tend to obscure the man and his work rather than shed much light. What makes a “great novelist”?

A writer is not simply the sum total of his literary gifts. Updike undoubtedly possessed those in abundance, and all of his novels contain passages, pages or more in which he exhibited a great ability to transform intricate human behavior and details of social life and nature into language. He had a truly remarkable eye and ear, and a deep feeling for what words had done in the past and could do.

However, a great writer must also have, in some fashion or other, “great” things to say. Not necessarily in the form of a single major theme or subject, but some sharper, distinctive insight, even if only partially conscious, into his or her times and contemporaries. Of course, Updike paid attention to social and political development in America, and, particularly later in his career, commented on various aspects of modern life: changes in values, the “sexual revolution,” the radicalism of the 1960s, feminism, the cultural wasteland that much of America had become and so forth.

But his purchase on these and other developments remained narrow, shaped by his upbringing and the intellectual framework established in postwar America. He described himself in 1988 as “a product of nearly forty years of the Cold War.” And an all-too uncritical product, in my opinion, who accepted at face value many of the self-serving arguments of the US establishment, including “the idea that communism represented a threat to American democracy, the sense that Americans were competing with a dangerous superpower for global supremacy…[the notion] that the communist system is antithetical to the basic right of individual freedom,” as D. Quentin Miller suggests in John Updike and the Cold War: Drawing the Iron Curtain.

While Updike rummaged widely and provocatively through American life, finding much to dislike or criticize, his vision of things rarely went beyond those circumscribed limits. As the article below suggests, Updike came of age during a period of cultural regression in the US, at the height of the anti-communist purges, which made a left-wing critique of American life far more inaccessible. His own small-town, Protestant, lower middle class, rather smug background (for which Miller claims he always maintained “a painful longing”) and psychological predisposition made him vulnerable to the prevailing orthodoxies.

The need to bend the truth, avoid certain realities, above all, not look too probingly at America’s social foundations affected his art, deflecting it and blunting it. In the more than 20 novels, there is far too much waste, secondary material, running in place, even showing off. As well, frankly, there is a good deal of mean-spiritedness directed toward those who fall outside of or reject Updike’s limited middle-class American universe.

In the end, his remarkable literary gifts and intelligence, his acute ability to see through certain subterfuges and stratagems, at least within private relations, served to conceal from the majority of his readership and perhaps himself the greater failings.

That being said, it is a mistake on the part of anyone who wants to know something about American life and the American psyche in the last 50 years to avoid John Updike’s work. He is generally interesting, often very amusing and sometimes insightful. His best writing was probably invested in the Rabbit Angstrom series, as noted below, especially Rabbit Run (1960) and Rabbit at Rest (1990). The Centaur is also recommended.

In 2006, the WSWS reviewed Updike’s novel, Terrorist, which would turn out to be his second to last. We are reposting the comment here, because it offers a brief overview and assessment of the writer’s career.

* * *

John Updike’s Terrorist

By David Walsh

25 August 2006

John Updike, Terrorist, New York, Alfred A. Knopf 2006, 310 pp.

Terrorist by American novelist John Updike is poorly conceived and unconvincingly written. It tells the story of a New Jersey teenager, Ahmad Mulloy-Ashmawy, the son of a long-absent Egyptian father and an Irish-American mother, who has chosen Islamic righteousness, “the Straight Path,” in the face of American decay and corruption.

Updike sets his 22nd novel in the city of New Prospect, a fictionalized Paterson (home to a large Arab-American population), a depressed industrial town in northern New Jersey. While Ahmad is ostensibly the central figure in the novel, he is strangely static and passive, stiffly reiterating at every opportunity his devotion to the “true faith” and excoriating American moral laxness.

Around him circle more active characters: his mother, Terry Mulloy, a nurse and amateur painter; his black fellow high school student, Joryleen Grant, for whom Ahmad has suppressed feelings; Shaikh Rashid, his spiritual teacher at a second-floor mosque situated “above a nail salon and a check-cashing facility”; his eventual boss, Charlie Chehab, at Excellency Home Furnishings; and, perhaps most significantly, the world-weary Jack Levy, Ahmad’s high school guidance counselor.

A struggle for Ahmad’s soul, more or less, takes place between Levy (linked, implausibly, to the Secretary of Homeland Security through his wife’s sister, the assistant to the secretary) and the Yemeni imam, Shaikh Rashid, who introduces him to a jihadist terror cell in New Jersey. In the end, Updike’s simplistic schema bears far too much resemblance to the Bush doctrine in which, on a world and national scale, “there is no neutral ground between good and evil.”

Apart from the author’s vivid portraits of New Prospect’s tawdriness and decline, and even those need to be considered critically, not much in the book stands up. Ahmad is thoroughly unlikely as a human being. Updike’s forewarning that “the boy speaks with a pained stateliness” is not sufficient to convince us that any American-born 18-year-old carries on like this (in a conversation with Levy): “I am the product of a white American mother and an Egyptian exchange student; they met while both studied at the New Prospect campus of the State University of New Jersey…. My father well knew that marrying an American citizen, however trashy and immoral she was, would gain him American citizenship, and so it did, but not American know-how, nor the network of acquaintance that leads to American prosperity. Having despaired of ever earning more than a menial living by the time I was three, he decamped. Is that the correct word?” This is very weakly done and places Updike in a bad light.

Foolish and unreliable as well is the actual course of the narrative. Ahmad’s transformation into a would-be terrorist fails every test. Yes, he has taken to a strict version of Islam, and much in American life disgusts him, the imam has become something of a father figure to him, and, yes, he is psychically and sexually at odds with the world around him—but these elements, by themselves, cannot possibly account for such a potentially homicidal trajectory.

Updike leaves out of account two critical sets of facts and does so because of his own conservative social outlook. First, the ability of an individual or individuals, like Timothy McVeigh or the Columbine high school killers, to commit deliberate mayhem on his or their fellow human beings bespeaks an increasingly callous and alienating society. The type of calculated mass murder that Updike pretends to imagine can only emerge from a deeply diseased social organism.

As a defender, in the final analysis, of American capitalist society (although not its citizens), Updike will admit of no such state of affairs. While physical decline abounds in Terrorist, there is no indication that the author perceives any great upheaval in ordinary human relationships. The various figures carry on, as they have in Updike’s novels for decades, in their normal chaotic, erotic and messy fashion. History leaves that untouched. Insofar as Updike imagines a change, it is largely a function of the growth in clichéd thuggishness, exemplified by Joryleen’s boy friend and future pimp, Tylenol Jones (“His mother … saw the name in a television commercial for painkiller and liked the sound of it,” Updike sneeringly writes), or equally clichéd cynicism (Jack Levy, above all).

Second, and a related phenomenon, the novelist more or less separates out Ahmad’s seamless willingness to take part in a terrorist plot from any questions of US policies in the Middle East. While others occasionally refer to Iraq and Palestine, including Charlie Chehab, who is not what he at first appears to be, Ahmad hardly ever does.

This is in keeping with the arguments of various right-wing pundits that Islamic fundamentalist terrorism has nothing to do with predatory US foreign policy over the course of decades and stems, rather, from a long-standing “clash of civilizations.” Updike, as a supporter presumably of the “global war on terror,” goes along with this unsustainable reasoning. He met with widespread and deserved opprobrium in the late 1960s for his support of Lyndon Johnson and the war in the Vietnam.

In an interview with Charles McGrath of the New York Times, the novelist observed that he originally contemplated creating “a young seminarian who sees everyone around him as a devil trying to take away his faith…. The 21st century does look like that, I think, to a great many people in the Arab world…. I think I felt I could understand the animosity and hatred which an Islamic believer would have for our system.”

Of course, the purely religious matters are an issue, but Updike conveniently (and condescendingly) abstracts from the equation the rage felt in the Arab and Muslim world for the real machinations of imperialism, the US in the forefront, which oppresses and brutalizes countless millions. The heinous terrorist acts of September 11, 2001, cannot be condoned, but they can be explained. One must say that Updike abandoned a serious attempt to account for them before he began his book.

The writer’s decision to include a quasi-sympathetic portrait of the Secretary for Homeland Security (hickish, bumbling, sincere) is simply disgraceful. Updike has his character declare, “My trouble i s…I love this damn country so much I can’t imagine why anybody would want to bring it down. What do these people have to offer instead? More Taliban—more oppression of women, more blowing up statues of Buddha.” Later, the novel argues that the Secretary’s task “is to protect in spite of itself a nation of nearly three hundred million anarchic souls.” The real directors of Homeland Security operations in the US, contrary to this fairy-tale, are in the business of substituting a police-state for constitutional rule.

In the same interview with McGrath, Updike perhaps lets one of the cats out of the bag. Discussing the brief love affair between Ahmad’s mother and the school guidance counselor, he remarks, “I was happy—because there was so much shaky ground in the writing of this novel—when Jack began to hit on Terry Mulloy…. I felt I was in a scene I could handle. That little romance was very real—to me, at least. I liked those two because they’re normal, godless, cynical but amiable modern people.”

Updike is quite right. The scenes of the two middle-aged lovers are the most relatively convincing in Terrorist, and come largely as a relief.

The writer’s difficulties with terrorism and politics occur within a broader context: his inability to come to terms in a profound manner with contemporary American social reality. The overriding sentiment conveyed by Updike, intentionally or otherwise, in his imagining of New Prospect, New Jersey, is disgust for the population.

The novelist is unsparing, and so he should be, in describing the physical circumstances in which the town’s inhabitants live. Images of urban decay abound. The high school building, for example, “rich in scars and crumbling asbestos…sits on the edge of a wide lake of rubble.” This latter phrase, “lake of rubble,” is repeated numerous times; in fact, various locales are identified by their proximity to it.

As Ahmad and Joryleen walk along in one scene, the “neighborhood grows shaggier around them; bushes are untended, houses unpainted, sidewalk squares in places tilted and cracked by tree roots underneath; the little front yards are speckled with litter. The rows of houses lack a few, like teeth knocked out, the gaps fenced in but the thick chain-link fencing cut and twisted….” Updike notes the “asphalt avenue…with its patched and repatched potholes and the tarry swales created by the constant weight of rushing cars and trucks….” Jack Levy bitterly sees an America “paved solid with fat and tar, a coast-to-coast tarbaby where we’re all stuck.”

Updike is quite right to be appalled by much of what he sees. There is an awfulness, a material and spiritual poverty, affixed to so much of American life, and no one ought to conceal the fact. However, who and what are responsible for this state of affairs?

In Updike, the revulsion at the physical deterioration bleeds into a repugnance with the population itself. The high school teachers are said to be “scuttling after school into their cars on the crackling, trash-speckled parking lots like pale crabs or dark ones restored to their shells.” This image of animal- or insect-like creatures recurs in the book’s final paragraph, with its reference to Manhattan pedestrians “all reduced by the towering structures around them to the size of insects, but scuttling, hurrying, intent in the milky morning sun upon some plan or scheme or hope they are hugging to themselves, their reason for living another day, each impaled live upon the pin of consciousness, fixed upon self-advancement and self-preservation. That and only that.”

Considered individually, Terrorist’s cast of characters proves to be rather pitiable and contemptible as well: Ahmad, with his puerile, adolescent fanaticism; Joryleen, patronizingly treated by the author, who ends up a prostitute; the quasi-bohemian Terry, full of delusions about her painting; Jack, who has come to the conclusion “that people stink,” and that he himself gives off a “stale aroma,” and so on. For all his verbal skill, it should be added, Updike here is largely working off stereotypes.

The author has chosen not to imbue his portrait of a decrepit, hollowed-out and rudderless community with any sense of protest. The often hostile tone the work assumes toward its human figures draws one on to the ineluctable conclusion that the fault for the mess lies with them, these scurrying, selfish, odorous beings. What sort of world could one expect such people to create? Apparently they deserve the cluttered, uncultured, ugly America they get.

In his gloominess about his fellow Americans, or at least a good portion of them, Updike has reached a sorry pass. This has consequences for his art. The work’s more or less happy conclusion, Ahmad’s “seeing the light,” as it were, with Jack Levy’s assistance, is rendered impossibly flimsy and implausible by everything that has gone on before. Divine intervention perhaps? Updike is a believer, but he has hitherto rejected a directly religious presence in his work, arguing that “Fiction holds the mirror up to the world and cannot show more than this world contains.” And this world does not contain an adequate explanation for Ahmad’s trajectory.

In sum, Updike has gotten recent American life, including September 11 and its consequences, terribly wrong. Is it not a commentary on the state of the American intelligentsia, such as it is, that a leading man of letters (and Updike is that, whether one approves of his body of work or not) should be so dangerously mistaken about critical events?

Updike remains an enormously gifted writer. Very few Americans have ever put words together as effectively as he. However, an artist is not free to do as he or she pleases and works, in fact, under definite historical and historically shaped intellectual conditions. Updike, born in 1932, grew up in the small town of Shillington, Pennsylvania (near Reading in the southeastern part of the state), son of a high school science teacher and grandson of a Presbyterian minister, and came of age during the Cold War.

The need to champion the “free world” against “communism,” of course in a sophisticated and literate fashion, stayed with him. (His first novel, The Poorhouse Fair (1959), in part, is a rather mean-spirited attack on the welfare state and any attempt at “socializing” American life.) In Rabbit at Rest (1990), one of Updike’s finest books, his long-running character, Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, remarks laconically, “Without the cold war, what’s the point of being an American?” (The comment, interestingly, was cited by Samuel Huntington, author of The Clash of Civilizations, in Foreign Affairs magazine in 1997.) However ironically intended, the words shed considerable light on Updike’s evolution.

On the basis of liberal anti-communism (“blacklists, congressional show trials and meaningless, redundant loyalty oaths for a time gave patriotism an ugly face,” he later wrote), Updike was able to explore “the whole mass of middling, hidden, troubled America” (his words) with some degree of honesty in novels such as Rabbit Run (1960) and The Centaur (1963). As the name of his most prominent character, “Angstrom,” suggests (“angst” = anxiety or apprehension), Updike, a lifelong churchgoer and student of Christian theology, was initially influenced by thinkers such as Søren Kierkegaard, the nineteenth-century melancholy Dane, and theologian Karl Barth.

As to the latter, a commentator writes, “The principal emphasis in Barth’s work…is on the sinfulness of humanity, God’s absolute transcendence, and the human inability to know God except through revelation. His objective was to lead theology away from the influence of modern religious philosophy back to the principles of the Reformation and the prophetic teachings of the Bible.” Not very attractive, and Updike weaned himself from Barth’s influence to a certain extent in middle age, while remaining a devout Protestant.

This is not the occasion for an in-depth accounting of Updike’s religious philosophy, if such an accounting be warranted. What strikes one most forcefully about the novelist’s “theological” concerns is the extent to which they form part of an overall cultural regression in the postwar period. Updike speaks of a certain “religious revival” in the 1950s, but such a phenomenon could only have taken place as part of a serious intellectual falling off, made possible in large measure by the purging of left-wing ideas from American cultural life.

After Twain, Mencken, Dreiser, early Dos Passos, Fitzgerald, early Hemingway, Sinclair Lewis (for all his limitations), Richard Wright of Native Son, the Harlem Renaissance members, and Steinbeck, O’Neill, Sherwood Anderson and Faulkner, for that matter, as well as other lesser figures, are we to arrive at this: “an unavoidable, unbearable, and unbelievable Sacred Presence,” which Updike believes we will find in his fiction; “the yearning for an afterlife [which]…is love and praise for the world we are privileged, in this complex interval of light, to witness and experience”; and the demand that we “examine everything for God’s fingerprints”? It’s the concentrated provincialism, self-limitation and, to be blunt, banality of many of the concerns that is most disturbing, and, in the end, has proven most harmful to Updike’s art.

Updike’s explorations of certain aspects of small-town, lower middle class American life in portions of the Rabbit Angstrom series are irreplaceable, as is his encounter with the surreal hideousness of Florida’s Gulf Coast in Rabbit at Rest (admittedly an easy target). However, and this is a great inadequacy, Updike has rarely been able to truly empathize with (and recreate artistically) anyone who does not resemble himself in important ways, in particular in his search for and belief in the “transcendent.” (This quality, in fact, is what saves Ahmad in Terrorist, unconvincingly.)

A thorough consideration of “middling, hidden, troubled America” would have required a far different, more critical starting point. In Rabbit Redux (1971), a contrived consideration of 1960s radicalism (one of Updike’s bête noires), Harry Angstrom announces that he has learned the US is not perfect; however, “Even as he says that he realizes he doesn’t believe it, any more than he believes at heart he will die.” The general acceptance of the status quo has had a paralyzing effect on the American literary arts and cinema over the past half-century.

In Updike, one sees a certain cultural process in concentrated form: the accumulation of great formal, technical skill at one pole, and the severe weakening of the artist’s understanding of history and social organization at the other.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

wsws.org are indeed lucky to have him as one of their own.

Let’s keep this award-winning site going!

Yes, audiences applaud us. But do you?If yes, then buy us a beer. The wingnuts are falling over each other to make donations…to their causes. We, on the other hand, take our left media—the only media that speak for us— for granted. Don’t join that parade, and give today. Every dollar counts.

|

|

| Use the DONATE button below or on the sidebar. And do the right thing. Even once a year. |

Use PayPal via the button below.

THANK YOU.

//

Hedren had grown up in Minnesota and had wanted originally to be a skater. When younger, she was “so painfully shy” that she would walk to and from school, head down, biting her nails, “until one day when I thought, then and there, ‘I’m going to stop biting them’, and I did”.

Hedren had grown up in Minnesota and had wanted originally to be a skater. When younger, she was “so painfully shy” that she would walk to and from school, head down, biting her nails, “until one day when I thought, then and there, ‘I’m going to stop biting them’, and I did”.