12 In the decollectivization of the rural economy in the early 1980s, collective enterprises were transformed into township and village enterprises (TVEs) that were later controlled or privatized by individuals. In 1990, nearly one-fifth of rural laborers were working in TVEs; in 2010, this number became one-third.13 Moreover, since the early 1990s, more and more rural laborers have migrated to urban areas; in 2011, the number of migrant workers reached 159 million, or 44 percent of total urban employment.14 However, due to the high cost of housing, education, and medical care in the urban areas and relatively low wages that migrant workers can earn, most cannot live with their families in the urban areas.

For a typical rural family, wages from working in TVEs or in the urban areas make up a large portion of the family’s income, while some of the family members (especially aging parents and young children) still need to engage in agricultural production and live in the rural areas, since the living cost in these areas is much lower. In this context, capitalists are not required to pay wages sufficient for the laborers to reproduce the labor power in the urban areas, and the agricultural income and the rural society becomes indispensable for the reproduction of labor power of their families.

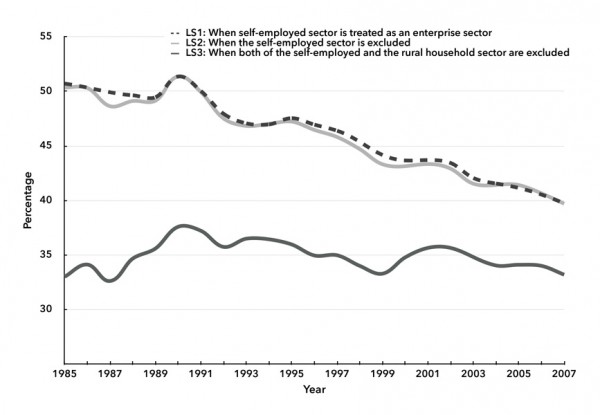

Therefore, although LS3 does describe something about distribution, it meets with a theoretical contradiction: the labor’s income implied by LS3 cannot satisfy the need of the working class to reproduce labor power. The distribution process in reality takes the semi-proletarianization of migrant workers and their families as its foundation. In this process, the working class makes use of both wage income and agricultural income to complete the reproduction process, and the capitalists take advantage of the double roles played by the working class to pay fewer wages. Excluding agricultural income from the calculation of labor’s share oversimplifies the distribution process because it ignores the internal relationship between workers and peasants in the reproduction of labor power and the reliance of the working class on the rural society. In contrast, LS1 and LS2 are better measures of labor’s share as they consider agricultural income as an integral part of labor’s income.

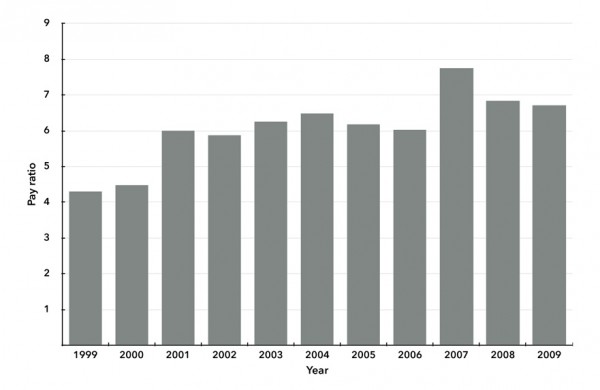

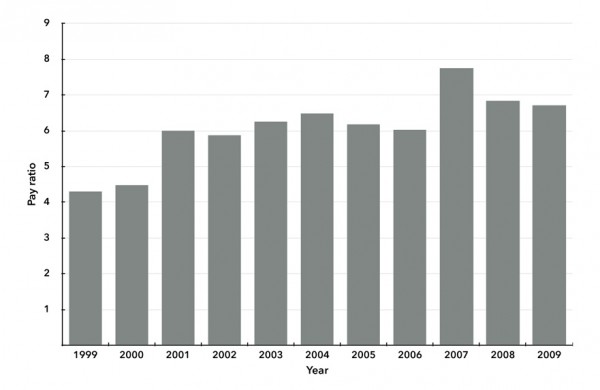

The last problem with measuring labor’s share is the salaries of managers. Under the socialist statistical system, China was collecting data on the salaries of cadres in factories, since the state attempted to control the income gap between cadres and workers, while after China replaced the socialist statistical system with the GDP accounting system in the early 1990s, these data were no longer collected. Nevertheless, from the data of the companies listed in China’s domestic stock markets, we can compare the average salary of managers, including board members, supervisors, and executives, with the average wage of urban employees in the formal sector.15 As shown in Chart 3, from 1999 to 2009 the ratio of the managers’ average salary to the urban average wage increased from 4.2 to 6.7, or by 60 percent. This implies that, if managers’ salaries are excluded from labor’s income, it is very likely that labor’s share in fact dropped more quickly in the past decade.

Chart 3. Ratio of Managers’ Average Salary to Urban Average Wage

Sources: Data of managers’ salaries are from Guotaian Database. The urban average wage is from National Statistical Bureau, China Statistic Yearbook 2012 (Beijing: China Statistics Press, 2012) (in Chinese).

Class Power and Labor’s Share

Labor’s share is widely used in Marxian economics as a proxy for the power of the working class. In China, labor’s share as an outcome of distribution is closely associated with the transition to capitalism, and this relationship can be observed in the transition of incentive systems on the shop floor.

In the Maoist era, there was a recurring debate on “material incentives” and “politics in command” during the transformation of incentive systems. Although a Soviet wage system was established in 1956, there was a lack of consensus among the leadership on how to operate this wage system.16 In particular, given that the Soviet Union underscored the role of material incentives, there was a debate on whether material incentives such as bonuses and piece-rate wages should be encouraged in China.

Mao Zedong was critical of this, and he suggested that the emphasis on material incentives was a reflection of the ignorance of political and ideological work. Mao argued these incentives merely underscored distribution according to work, but do not underscore the contribution of individuals to socialism.17 Thus the proponents of “politics in command” proposed an entirely new path to generate work incentives. The key of the new path was to make workers recognize that they themselves were the masters of factories, and the purpose of production was consistent with the long-run interests of the working class.18 To this aim, material incentives that merely relate workers’ contribution with their short-run economic benefits were eliminated, workers were encouraged to participate in the management of factories in various ways, and the income gap between workers and cadres was controlled since significant inequality would be contradictory to workers’ position as the masters of factories.

With the end of the Maoist era, the first attack against the working class was the deprivation of political rights that the workers had gained. The mass organizations established during the Cultural Revolution were dismissed; radical workers were criticized and punished; the four great rights—the right to speak out freely, to air one’s views fully, to write big-character posters, and to hold great debates—as well as the right to launch strikes were all eliminated in the 1982 amendment of China’s Constitution. Now, workers could no longer criticize cadres. Without the participation of workers in management, the Maoist incentive system lost its foundation and the material incentive system eventually took its place.

From the reformers’ point of view, the material incentive system could play important roles. First of all, material incentives, as compensation for workers’ loss of political rights, shifted workers’ attention from political rights to economic benefits. Secondly, through material incentives the reformers attempted to set up an image that they, in contrast to the leadership in the Maoist era, cared more about the living conditions of workers and the fairness in distribution. Thirdly, material incentives strengthened the power of cadres in management since cadres could decide how to distribute bonuses among workers.

From the position of the working class, the material incentive system benefited workers in the short run but sacrificed their long-term interests. Bonuses could grow as quickly as labor productivity did, but this does not imply that workers’ total wages (including bonuses) could catch up with labor productivity. As workers’ income increasingly relied on bonuses, workers had to be more obedient to cadres in production, which in turn meant that workers were in an unfavorable position with respect to distribution.

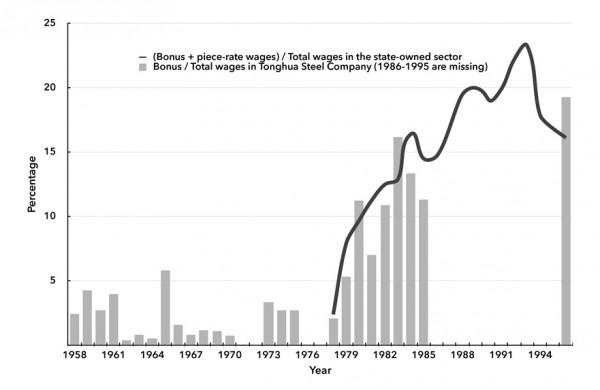

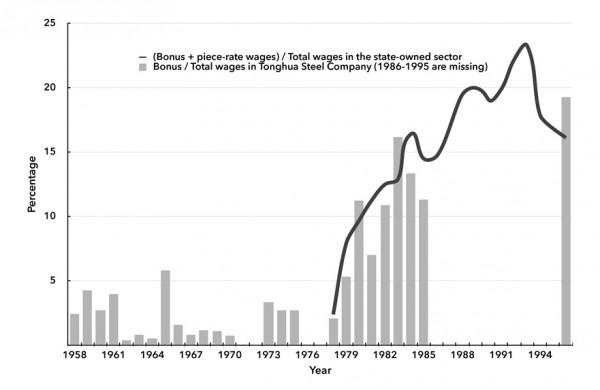

Chart 4 shows the bonus-wage ratio—the ratio of bonuses to total wages—for the Tonghua Steel Company and the state-owned sector as a whole (including SOEs and non-enterprise units such as government institutions). For the steel company, this ratio reached its peak at 4.2 percent in 1959, while in several years of the 1970s this ratio fell to zero. After the Maoist era, the bonus-wage ratio boomed and reached around 20 percent for the state-owned sector. This high bonus-wage ratio was not able to sustain itself; after 1993, this ratio dropped, and in 1996, it returned to the level of ten years earlier.

Chart 4. Bonus-Wage Ratio in Tonghua Steel Company and in the State-owned Sector, 1958–1996

Sources: The bonus-wage ratio of Tonghua Steel Company is from Tonghua Steel Company, Tonggang History 1958–1985(unpublished book; in the Tonghua City Library). The bonus-wage ratio of the state-owned sector is from National Statistical Bureau, China Statistic Yearbook various issues from 1981 to 1997 (Beijing: China Statistics Press) (both in Chinese).

Note: The bonus-wage ratio of the state-owned sector is not available; instead the ratio of the sum of bonuses and piece-rate wages to total wages has been used.

It is not difficult to figure out why the bonus-wage ratio failed to sustain its growth. The viability of material incentives relies on the growth of labor productivity, as the former cannot be generated without the latter. If enterprises are affected by macro fluctuations (as in the mid–1990s), the growth of labor productivity cannot be realized and thus material incentives would not function.19 Under this circumstance, the power of the management was threatened by the problems with the incentive system. For a capitalist enterprise, if the carrot of material incentives does not work, the stick strategy would take its place—capitalists would create unemployment so as to discipline workers. In the early 1990s, however, the management in China’s SOEs did not have the power to fire workers unless workers made serious mistakes such as crimes.

If it were impossible to tame the workers who had socialist experience from the Maoist era, the rational strategy for enterprises was to segregate the labor market in order to explore new sources of labor power, and the state indeed responded to this imperative. The early 1990s witnessed policy changes that reduced barriers for migrant workers to work in the urban areas.20 In the following two decades this new component of the Chinese working class suffered from long working hours and poor working conditions. A 2009 survey from the National Bureau of Statistics has shown that on average migrants work 58.4 hours per week, much more than the 44 hours stipulated in China’s Labor Law. Nearly 60 percent of migrant workers did not sign any labor contract, and 87 percent of them did not have access to health insurance.21 The segregation of the labor market in the early 1990s could provide enterprises with a larger labor force, but without the stick of unemployment the SOEs could never undermine the power of their workers.

In the mid–1990s, China launched a massive privatization of SOEs. Along with this privatization, about 30 million workers were laid off.22 This was a crucial turning point in Chinese capitalism that fundamentally altered the power relations between workers and capitalists. Workers with socialist experience were forced to leave factories, whereas young workers without socialist experience became the majority of the labor force in SOEs. Due to this change, institutions in SOEs began to converge with those in private enterprises: short-term labor contracts, dispatched workers, and overtime work became the routine in both SOEs and private enterprises.23

After the reform, despite the convergence of the institutions on the shop floor, the labor market on the contrary became more segregated. In the center of the labor market was a group of skilled workers in SOEs who enjoyed relatively high wages, benefits, and job security; whereas on the periphery were the laid-off workers and migrant workers who received low wages and benefits with less job security. The segregation of the labor market was clearly observed in the statistics. In 2011, there were 359 million urban employees in total; among them only 19 percent worked in the state-owned sector; another 21 percent worked in the formal sector excluding the state-owned sector; 34 percent worked in the informal sector—either in private enterprises or in the self-employed sector. Ironically, the remaining 26 percent of urban employees (or 97 million employees) turned out to be “invisible” for the National Statistical Bureau because they did not know which sector those employees should belong to.24 In fact, the “invisible” employees were mostly migrant workers working in private enterprises or in the self-employed sector; their jobs were so informal that they were not registered in any way.

To sum up: during the country’s transition to capitalism, as the bonus-centered incentive system could not sustain itself, enterprises needed the existence of a reserve army to discipline workers and a segregated labor market to divide and conquer the working class. A continuous influx of migrant workers and the 30 million laid-off workers from the state-owned sector jointly expanded the reserve army of labor within a few years in the 1990s. The reserve army significantly depressed the power of the working class as a whole, and the segregation of the labor market also weakened the solidarity of the working class. This is why we have witnessed the major decline of labor’s share since the early 1990s.

Conclusion

There is a new turning point for the Chinese working class.25 After the outbreak of the global capitalist crisis, labor’s share in China began to recover. Along with this fact, one can also observe that the nominal wage level has grown faster than nominal GDP since 2008, and in 2012 China’s working-age population decreased for the first time in the reform era, which implies that the reserve army of labor will shrink in the near future.26 More importantly, there is a developing workers’ struggle for a decent living wage that is sufficient to afford the cost of living in the urban areas. The new generation of migrant workers who were mostly born in the 1980s and ‘90s insists on living in the urban areas. This has led to struggles for higher wages. Workers’ struggle for a larger share of the national income will eventually end the high-profit era for capitalists and thus open up a new era for the Chinese economy.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Hao Qi hqi [at] econs.umass.edu is a PhD candidate of the department of economics at University of Massachusetts Amherst. His research interests include Marxian political economy and income distribution.

Notes

- ↩See Andong Zhu and David Kotz, “The Dependence of China’s Economic Growth on Exports and Investment,”Review of Radical Political Economics 43, no. 1 (2011): 9–32.

- ↩See Chong-en Bai, Chang-Tai Hsieh and Yingyi Qian, “The Return to Capital in China,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 37, no. 2 (2006): 61–102.

- ↩On July 24, 2009, workers at the Tonghua Steel Company launched a strike and beat the general manager to death. The Tonghua Steel Company was a state-owned enterprise that was privatized through a local government-led program by introducing a “strategic” private shareholder in 2005. After privatization, the company laid off workers, constrained wage growth, and cut benefits such as the heating subsidy, while the management gained huge bonuses through privatization. This struggle forced the local government (the biggest shareholder) to introduce another state-owned enterprise to replace the private shareholder.

- ↩In China’s reform era, agriculture as a percent of GDP has declined from 28.2 percent to 10.0 percent, the service sector as a percent of GDP has increased from 23.9 percent to 43.4 percent, and the share of industry has been roughly stable. Sources: National Statistical Bureau, China Statistic Yearbook 2012 (Beijing: China Statistics Press, 2012) (in Chinese).

- ↩See National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Finance, and Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, “Some Opinions on Deepening the Reform of the System of Income Distribution,“ http://gov.cn (in Chinese).

- ↩This example is from my interviews.

- ↩Ibid.

- ↩National Statistical Bureau, China Statistic Yearbook 2012.

- ↩Cai Fang, “The Consistency of China’s Statistics on Employment,” Chinese Economy 37, no. 5 (2004): 74–89.

- ↩This example is from my interviews.

- ↩Pan Ngai and Lu Linhui, “Unfinished Proletarianization: Self, Anger, and Class Action Among the Second Generation of Peasant-Workers in Present-Day China,” Modern China 36, no. 5 (2010): 493–519. Tu Lv, Chinese New Workers (Beijing: Law Press, 2012) (in Chinese).

- ↩National Statistical Bureau, China Statistic Yearbook 2012.

- ↩The sample is from Guotaian database, which provides the information about the salaries of about 30,000 board members, supervisors, and executives in the listed companies in China. The formal sector includes state-owned units, collective-owned units, cooperative units, joint-ownership units, limited liability corporations, share-holding corporations, foreign-funded units, and units with funds from Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan.

- ↩The Soviet wage system in China featured an eight-grade scale for workers and separate scales for cadres and technical staff.

- ↩Mao Zedong, Mao’s Notes and Talks on Reading Socialist Political Economy (Beijing: National History Academy, 1998) (in Chinese).

- ↩See Stephen Andors, China’s Industrial Revolution: Politics, Planning, and Management, 1949 to the Present (New York: Pantheon Books, 1977).

- ↩Deng Xiaoping’s southern tour in 1992 triggered an investment boom which further led to continuous inflation in the following years. In 1994, the government decided to restrain banking credit to deal with inflation. This policy succeeded in controlling inflation but meanwhile depressed the profitability of enterprises.

- ↩In the 1980s, the government strictly controlled the migration of labor forces. Migrant workers were called the “blindly floating population.” In the 1990s, most of the constraints on migrant workers were eliminated, whereas workers were still facing the possibility of being repatriated. See Tu Lv, Chinese New Workers (Beijing: Law Press, 2012) (in Chinese).

- ↩National Statistical Bureau, “Investigation Report on Migrant Workers 2009,” http://stats.gov.cn (in Chinese).

- ↩The number is estimated by the reduction in the employment of the state-owned sector from 1995 to 2000. Data is from National Statistical Bureau, China Statistic Yearbook 2012.

- ↩In the interviews with some workers in SOEs, I found that new workers in SOEs mostly signed three-year-long labor contracts, and dispatched workers, who were hired by external labor agencies but worked for SOEs, were quite common in construction and transportation. Many of my interviewees complained about overtime work, and one interviewee who had working experience in both SOEs and private enterprises said that there was no difference with regard to overtime work in both kinds of enterprises.

- ↩National Statistical Bureau, China Statistic Yearbook 2012. Philip Huang suggests that the statistical apparatus in China neglects this part of employment because of the misleading influence of mainstream economic and sociological theories. See Philip Huang, “China’s Neglected Informal Economy: Reality and Theory,” Modern China35, no. 4 (2009): 405–38.

- ↩Minqi Li, “The Rise of the Working Class and the Future of the Chinese Revolution,” Monthly Review 63, no.2 (2011): 38–51.

- Statistical Communiqué of the People’s Republic of China on the 2012 National Economic and Social Development,” http://stats.gov.cn (in Chinese).