THIS WEEK IN CHINA # 0001 (DATELINE: 8 Aug 2020)

Gleanings from the Middle Kingdom

The size of China’s displacement of the world balance is such that the world must find a new balance. It is not possible to pretend that this is just another big player. This is the biggest player in the history of the world. – Lee Kwan Yew.

THE ECONOMY

Factory activity expanded in July for the fifth month in a row and at a faster pace, beating analyst expectations. The official manufacturing Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) rose to 51.1 in July from June's 50.9, the highest reading since March. Analysts had expected it to slow to 50.7.[MORE]

In a series of deals worth hundreds of billions, PipeChina recently acquired infrastructure assets from China’s three largest energy companies. Central state ownership of the nation's vast pipeline network, liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals and oil storage facilities will make it easier for smaller players to enter the energy sector and keep costs down.[MORE]

Tesla is advertising for another 1,000 Chinese factory workers and designers to join its studio as production ramps up. Q2 China revenues climbed 103% YoY to $1.4 billion, which means China generates 23% of Tesla’s total revenues compared to 11% last year.[MORE]

The world's biggest liquor company, Kweichow Moutai, said net income rose 13% in H1 2020. Earnings for the first six months were $3.2 billion and revenue jumped 11%. [MORE]

Tencent is now bigger than Facebook. After adding around $200 billion to its value this year, Tencent shares rallied around 43% year-to-date (compared to 12% for Facebook), adding $198 billion to Tencent’s value. [MORE]

TRADE WAR

As the chart above shows, China's membership in the WTO did not affect its manufacturing decline. [Cato Institute]

Moody’s says the trade war cost the U.S. economy 300,000 jobs and 0.3% of GDP. Bloomberg says it will cost $316 billion this year, while the New York Fed found that US companies's stocks lost $1.7 trillion as a result of the tariffs. Companies paid $46 billion in tariffs, forcing them to accept lower profit margins, cut wages and jobs, defer potential wage hikes or expansions, and raise prices for American consumers or companies and “farmers have lost the vast majority of what was once a $24 billion market in China”. The US goods trade deficit with China reached a record $419.2 billion. [MORE]

Russia more than doubled its meat exports in the first six months this year and China became the largest buyer of Russian meat, accounting for 45 percent of shipments. [MORE]

Russia and China are rapidly abandoning the US dollar. Four years ago the greenback accounted for over 90 percent of their currency settlements. In Q1 2020, the dollar’s share of their trade fell below 50 percent for the first time. [MORE]

COVID CORNER

A Chinese COVID-19 vaccine candidate is effective against all detected strains of the virus so far, with lower chance and degree of adverse reactions than same-typed vaccine candidates under research."The inactivated vaccine we developed can cover all strains of the coronavirus that have been detected so far, including the virus strains tracked in the Xinfadi market in Beijing". [MORE]

A Chinese COVID-19 vaccine candidate is effective against all detected strains of the virus so far, with lower chance and degree of adverse reactions than same-typed vaccine candidates under research."The inactivated vaccine we developed can cover all strains of the coronavirus that have been detected so far, including the virus strains tracked in the Xinfadi market in Beijing". [MORE]

COLD WAR

A new Harvard study revealing that Chinese citizens’ satisfaction with their government has increased since 2003: “There is little evidence to support the idea that [the Communist Party] is losing legitimacy in the eyes of its people … By 2016, the Chinese government was more popular than at any point during the previous two decades. As such, there was no real sign of burgeoning discontent among China’s main demographic groups, casting doubt on the idea that the country was facing a crisis of political legitimacy.” Just as interesting is the fact that it has received little media attention: how could an evil authoritarian regime attract such widespread support from people across China? –David Dodwell. [MORE]

Harvard professor Charles Lieber, accused of lying about China ties, faces new charges. Lieber, 61, was charged in June with lying to US Defence Department investigators about his relationship with WUT and for lying to Harvard about those connections, leading the university to share that false information with the US National Institutes of Health.[MORE]

The People’s Bank of China says the country should switch from SWIFT to a domestic financial network and drop the greenback as the anchor currency for its foreign exchange controls. It also recommended developing legislation similar to the European Union’s Blocking Statute, which allowed the EU to sustain trade and economic relations with Iran despite US sanctions.[MORE]

BELT AND ROAD

The China-Iran deal will change the balance of power in the Middle East. The manufacturing products created by utilizing cheap Iranian resources will be used to crack the western markets through the China-Iran axis along with unrestricted access to Iranian military bases. China will invest US $280 billion in expanding Iran’s oil, gas, and petrochemicals sectors, to be front-loaded into the first five-year period. Another US $120 billion will upgrade Iran’s transport and manufacturing infrastructure, this amount will increase in each subsequent period. Chinese companies will bid on any stalled or uncompleted oil, gas, and petrochemicals projects in Iran. China is granted the offer to buy oil, gas, and petchems products at a minimum discount of 12 per cent to cover risk premia and volume discounts. “Provided ALL goes as planned, Sino-Russian bombers, fighters, and transport planes will have unrestricted access to Iranian air bases” at Hamedan, Bandar Abbas, Chabhar, and Abadan. [MORE]

HUAWEI

Great video explaining the dirty tricks behind the Meng case: https://youtu.be/SVhLvS9lCNs

Huawei is considering all possible options against HSBC for allegedly presenting “misleading evidence” that resulted in the arrest of its chief financial officer, Meng Wanzhou, in Canada. The tech giant has hired five law firms in an all-out effort to free Meng Wanzhou.[MORE]

Cynthia Chung: “HSBC has a lot to lose if its relationship to the Chinese government falters. In 2017, the first joint venture securities company majority owned by a foreign bank, HSBC Qianhai Securities Limited, was formally opened for business in China. Though this was a great achievement by HSBC, its foreign majority ownership is a mere 51%, which could be easily taken away if they were considered at any point to be unfit for that level of responsibility. Recently, HSBC also carried out the first transaction in yuan-denominated blockchain letters of credit. HSBC’s position at the forefront of facilitating blockchain trade in the yuan promises a way into a major market, with China-related trade producing an estimated 1.2 million letters of credit worth $750 billion last year”. [MORE]

ENVIRONMENT

The Yellow River is the clearest it’s been in 500 years, scientists say. A study found there has been a sharp reduction in run-off and sediment in recent decades that is unprecedented over the past five centuries. The change is a result of tree planting, less rainfall in the region and human activities like irrigation and tree-planting that use a lot of water. [MORE]

SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

The annual ranking of articles published in peer-reviewed science journals worldwide is now available from Scimago. Chinese scientists are widening their lead over US scientists every year, as we would expect, since the PRC invests four times more money in R&D than the US. Frans Vandenbosch kindly distilled it into this chart: [MORE]

China holds the most quantum computing patents, far more than the US Japan, or the UK says Chii Dong Chen, physics researcher at Taiwan's Academia Sinica. The US congress in December 2018 passed the National Quantum Initiative, planning to spend US$1.2 billion in five years to establish an office to organize quantum computing research. [MORE]

After a month in orbit, BeiDou passed its final test by locating a plane in flight while tracking and monitoring an air terminal. By the end of 2023, all civil aviation aircraft will have BeiDou-based positioning and tracking capabilities. Myanmar's Ministry of Fisheries has purchased 1,000 BeiDou shipboard terminals for vessel position information and tracking and 137 countries have signed cooperation agreements with BeiDou.100% of BeiDou's core components are made in China.[MORE]

Doctors have used gene editing to treat patients with thalassemia, the first time the technique has been successfully implemented in the country. Medical scientists at Central South University said those receiving the treatment had gone 87 days without blood transfusions.[MORE]

DEFENSE

CNBC reports that China is testing electronic warfare assets at fortified outposts in the South China Sea. The move allows Beijing to further project its power in the hotly disputed waters. [MORE]. China News reports that several US Growler electronic warplanes went out of control for a few second over the South China Sea then withdrew. According to the pilots, their instruments became chaotic and the planes could not communicate with the outside world. The United States demanded that China dismantle the electronic equipment immediately, but was ignored.[MORE]

Admiral Philip Davidson's Senate testimony:

- “China is pursuing advanced capabilities like hypersonic missiles which the United States has no defense against. As China pursues these advanced weapons systems, US forces across the Indo-Pacific will be placed increasingly at risk.”

- “China is now capable of controlling the South China Sea in all scenarios short of war with the United States.”

- “China is undermining the rules-based international order.” [MORE]

A new RAND Corporation report explores four scenarios of what extended competition between the United States and China might entail through the year 2050:

- triumphant China: Beijing succeeds in realizing its grand strategy

- ascendant China, in which Beijing achieves many, but not all, of its goals

- stagnant China, in which Beijing has failed to achieve its long-term goals

- imploding China, besieged by problems that threaten the communist regime's existence

The report concludes that a triumphant China is the least likely. [MORE]

Next year, ASEAN and China celebrate 30 years of bilateral relations and may upgrade it to form a 'comprehensive strategic partnership'. If they can all agree on a South China Sea Code Of Conduct by the end of 2020 it would invalidate US pretensions to secure “freedom of navigation” in an area where navigation is already free.[Pepe Escobar]

COLD WAR

Australia Tells US It Has No Intention of Injuring Important China Ties [MORE]

“Australia has made a principled call for an independent review of the COVID-19 outbreak, an unprecedented global crisis with severe health, economic and social impacts," said Foreign Minister Marise Payne. Australia was pushing for an investigation into China, not factual information about Covid-19.

Australia plans to set up US-funded military fuel reserve (in America!) amid China tensions [MORE]

The Royal Australian Navy guided-missile frigate HMAS Parramatta (FFH 154) is underway with the US Navy amphibious assault ship USS America (LHA 6),the Ticonderoga-class guided-missile cruiser USS Bunker Hill (CG 52) and the Arleigh-Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Barry (DDG 52) in the South China Sea.

Australia rejects China’s assertion that its sovereignty claims over the Paracel and Spratly Islands are ‘widely recognised by the international community’.Australia is making clear that it does not recognise the claims of China or any other states to these islands and that they remain a matter of dispute. In this respect, there has been no change to Australia’s longstanding position on the disputed status of the islands. [MORE]

Australia Pours Money Into Insane US War Games Yet Won’t Support Its Own Citizens. Australian government slashes pandemic payments to workers after suspending parliament. "Australia is not a real country, and it doesn’t have a real government," writes Aussie Caitlin Johnstone. "It is functionally nothing more than a U.S. military/intelligence asset. Despite a worsening COVID-19 surge in Australia’s two most populous states, the Liberal-National government yesterday announced the slashing of its pandemic wage subsidies and welfare benefits, as part of its drive to ‘reopen the economy.’" [MORE]

New Zealand Ramps Up Military Spending To Align With US and Australia Against China. New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s government, a coalition between Labour, the Greens and the right-wing nationalist NZ First Party, is committed to spending $20 billion on military upgrades.[MORE]

Australian Bureau of Statistics data shows that Chinese investment accounts for 2.0 percent of foreign investment in Australia: US: 25.6 percent; UK: 17.8 percent; Belgium: 9.1 percent; Japan: 6.3 percent; Hong Kong: 3.7 percent; Singapore: 2.6 percent; The Netherlands: 2.3 percent; Luxembourg: 2.2 percent.

The European Union agreed to restrict the export of equipment used for suppression and surveillance to Hong Kong. The European Council stated that it expressed serious concerns about the “Hong Kong National Security Law”, stating that the law has severely eroded the rights and freedoms that Hong Kong should be protected until at least 2047. German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas stated that it is reasonable to treat Hong Kong on the same basis as mainland China when exporting equipment for repression after the Hong Kong National Security Law takes effect.[MORE]. Review Hong Kong's 1997 Treason Ordinance here: [MORE]

“Canada, Australia and the UK have unilaterally suspended the agreements on surrender of fugitive offenders (SFO) with the HKSAR using the enactment of the National Security Law in Hong Kong as an excuse, which smacks of political manipulation and double standards. The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) Government has reciprocated.[MORE]

The International Air Transport Association objects to testing aircrew for Covid-19 as it predicts industry will not recover until 2024. New rules make it compulsory for pilots and cabin crew to have negative result before they can fly to Hong Kong. The IATA does not support the move, though evidence suggests that the latest surge came from imported cases.[MORE]

LONG READ

The Truth About Social Credit

The most authoritative Government release on Social Credit in some time is available for public comment through August 20th., and seeks to clarify critical concepts and concerns in building China’s Social Credit System such as

- What data can be collected or used as ‘Credit Information’?

- When information can be shared or made public and how?

- What penalties are allowed, and what procedures are to be used?

- How negative ‘credit’ can be restored?

The overall goal is to make sure that the system is part of the legal system, not something beyond it or parallel to it.

The backstory.

If you aren’t living in or studying China, you may well believe that the Social Credit System is an algorithmic reputation scoring mechanism based on “real-time monitoring through big data tools” to generate a score “controlling virtually every facet of human life” that “dictates one’s place in society“. The reality is both more complicated and far less exciting.

People would likely have a more accurate understanding of the system if China had said they were crafting a “Law on the Collection and Use of Administrative and Regulatory Data” instead of a ‘social credit system’. The ‘social credit’ name isn’t only evocative in English but also reflects the misguided attempt to include diverse topics such as financial credit reporting, administrative regulation, and public morality propaganda under the same project name, even though these pieces remained fairly discrete in practice.

It’s probably safe to say that the primary function of ‘social credit’ is one of administrative regulation, operating through industry-specific blacklists. Regulatory agencies were all tasked with generating rules for what violations of the laws under their authority would justify blacklisting. Blacklisting is important, not only because it creates a negative public record, but also because various agencies have signed inter-agency MOUs to take limited enforcement action against those blacklisted by another agency. Blacklisting by the food and drug administration, then, might result in consequences when applying for permits from an unrelated agency. This tool lets you explore the full range of cross-departmental punishments under this system.

Updating the Blacklists.

The new draft rules revisit the drafting of industry blacklisting standards and procedures to require both a serious violation of law AND:

- A threat to health or safety,

- disruption of the marketplace,

- violations of judicial or administrative orders, OR

- refusals to perform national defense duties.

The third category is about increasing the enforceability of court judgments and refers to the court system’s blacklist for ‘judgment defaulters’- those who have an active judgment against them and the ability to satisfy that judgment, but who refuse to do so. This one blacklist is overwhelmingly driving most of the exotic penalties connected with social credit, such as the no fly list and limits on spending. Interestingly, it is described as necessary to increase the ‘credibility’ of the courts.

The new draft rules also require that industry blacklisting standards now include express mechanisms for being removed from the list or correcting information. More importantly, the standards must be released for a period of at least 30 days for public commenting before they are enacted, and their implementation must be periodically evaluated by a third party after enactment.

Blacklisting Procedures

Before being blacklisted, parties must be given notice of the reason and the legal basis and have a chance to object. If blacklisted, they must be given a clear written decision indicating the reasons, rules for removal, and so forth. Blacklisting decisions should generally not be made below the county-level and are reviewed at the provincial level.

Punishments

All credit punishments must be listed in a national catalog of penalties drafted in conjunction with experts and other concerned parties. The draft rules make clear that punishments methods cannot require 3rd parties like banks and businesses to take action against blacklistees.

An explicit legal basis must be provided for all possible punishments.

This has actually been done in the past for inter-agency punishments authorized in cross-departmental MOUs mentioned above, although some have found that the scope of the cited authority may have been exceeded. Generally, however, the need for a legal basis has already limited cross-departmental action to areas where an agency has discretion to consider a broad range of factors- such as in permitting and licensing, with punishments generally been limited to:

- Higher scrutiny or restrictions in authorizing necessary permits, credentials, or approvals,

- Higher scrutiny or restrictions on participation in government contract bidding or authorization of use of government resources,

- Restrictions on receiving/ revocation of awards and honors.

- Increased routine regulatory oversight

- limits on receiving government benefits.

One of the greatest fears about the social credit system is that the ‘credit consequences’ for a violation could become a way of covertly increasing the violations’ statutory penalty. Meaning that since ‘untrustworthy conduct’ refers to violations of laws and legal obligations, there shouldn’t be any collateral consequences that increase the punishment beyond what the relevant law authorizes. A parallel might be the lasting impact of a criminal record long after a sentence has been served.

The new rules are at pains to say that this can’t be tolerated. There must be a legal basis for penalties and that if the law doesn’t allow for sufficient penalties, the correct approach is to lobby to amend the law, not use social credit, not only requiring a legal basis for penalties but also adding that if the law doesn’t allow for sufficient penalties, the correct approach is to lobby to amend the law, not use social credit.

Credit Information

A global concern today is the collection of personal information and the new rules attempt to regulate what information should be collected and used as ‘credit information’. The inclusion of ‘Public Credit Information’-the information collected or generated by government agencies in the course of their duties- in social credit is to be limited to the types of information in a national uniform catalog created by the inter-agency committee for establishing social credit with the input of legal experts, scholars, affected businesses, industry associations, and others. Local public credit information catalogs have been available for some time, but a national catalog will limit local discretion and help standardize the system.

The purpose of collecting or using information is also required to be indicated- and consent must be given for the collection of information that isn’t authorized by law. To try and ensure that consent is voluntarily given, the rules say that it must not be coerced or gamed through methods like demanding blanket consent. This follows recent moves on privacy in the commercial sector.

If something is to be considered negative credit information- it must be based on judicial rulings, arbitration documents, administrative decisions and rulings, or other effective legal documents. Again, social credit is concerned with recording and publicizing violations of laws and legal obligations.

Conclusion

The draft rules are open for public comment until August. As written, they would require that industry blacklist and social credit rules comply with them by the end of 2021 or be invalidated. Much of what they say is positive, but not groundbreaking in that they largely restate principles that were always in place or were emerging in practice over the past several years. Moreover, the draft, like much national level authority is quite vague, leaving room for future problems. The required national catalog of public credit information or punishment lists, for example, are yet to be seen, nor are specific mechanisms and procedures for credit restoration and corrections. The requirements that all standards and rules for punishments be made public may ultimately be among the most concrete improvements- allowing monitoring and analysis of the systems’ evolution.

Most critically, the main purpose of the draft is to harmonize social credit with China’s existing legal system, and while ‘legality’ should be a minimum requirement, it is no panacea. Many laws creating obligations or prohibiting conduct in China are unclear or easily abused. Others, that criminalize speech such as mockery of the national anthem are simply unjust. Limiting social credit to the enforcement of such laws, can’t improve those underlying laws. Sponsor a translation at the wonderful China Law Translate. [HERE]

Special Addendum

Which country has arguably the best judicial system in the world and why?

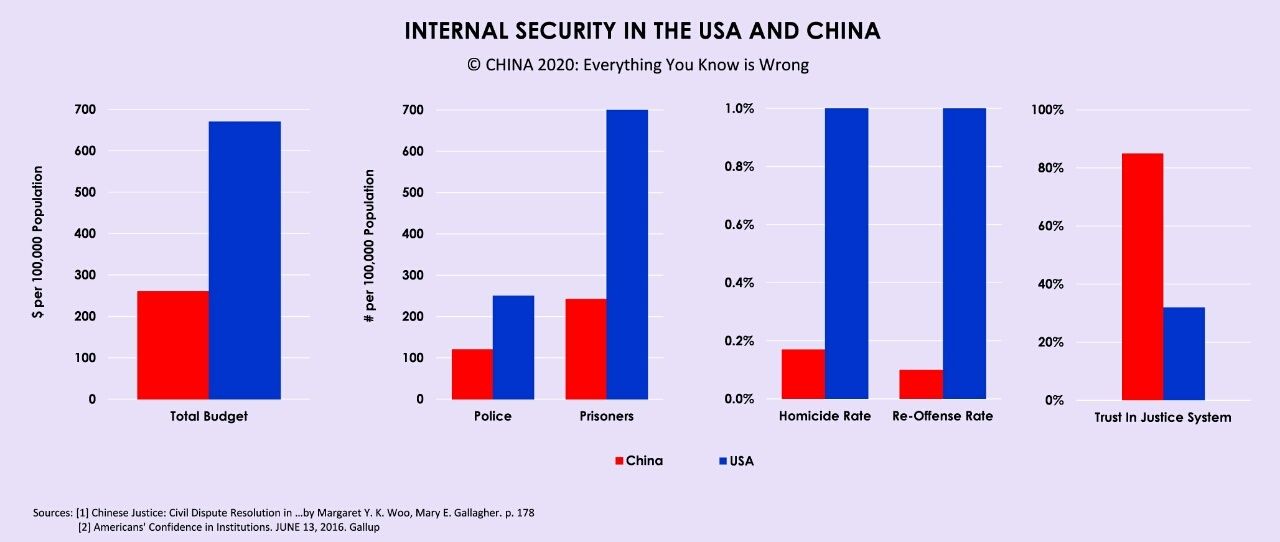

China has the best judicial system in the world because the sine qua non for a good judicial system is trust and people trust their legal system because it applies the law uniformly to rich and poor, powerful and powerless, alike.

If people do not trust their judicial system it has failed, and China’s judicial system is the most trusted on earth.

How do China and America compare? How much do citizens trust their respective legal systems?

When he launched his anti-corruption drive in 2012, President Xi promised1 to govern by virtuous example, yide zhiguo, and to create a socialist spiritual civilization, jingshen wenming. Four years later, reminded2 a judicial study group that law and ethics are inextricably bound:

Law is virtue expressed in words and virtue is law borne in people's hearts. In the eyes of the State, law and virtue have equal status in regulating social behavior, adjusting social relations and maintaining social order. Rule of law must embody moral ideals that provide reliable institutional support for virtue. Laws and regulations should promote virtuous behavior while socialist core values–prosperity, democracy, civility, harmony, freedom, equality, justice, the rule of law, patriotism, dedication, integrity and friendliness–should be woven into legislation, law enforcement, and the judicial process.

Penal law and judicial processes still play minor roles in Chinese everyday life and the legal process remains a work in process. Members of the National Family 3 still address older strangers as ‘aunty,’ ‘uncle,’ ‘grandfather,’ or ‘grandmother,’ and every adult assumes responsibility for every child. Would-be criminals struggle against family, friends, workmates, classmates, and neighbors who counsel, mediate and compromise4 with them to keep them on the path of virtue. They encourage self-criticism and use persuasion, education, and individually tailored solutions, which families can enforce far more effectively than police. So effective is mediation that Congress now requires all villages to maintain People’s Mediation Committees5, courthouses to maintain mediation offices, and lawyers to become certified mediators. In 2019, seven-million mediators handled six million disputes and reduced the national legal bill to one-tenth of America’s6.

As in France, magistrates are regarded as neutral truth seekers who interrogate suspects, examine evidence, hear testimony, render verdicts and determine guilt and innocence pre-trial. Though a Trial Spot in wealthy Shanghai provides defense lawyers for all criminal defendants, elsewhere defense lawyers are mandatory only for juveniles, the disabled, and those facing life imprisonment or death. If there is insufficient evidence for a conviction, the magistrate will suggest that the procurate either reduce the charges or investigate further. Since most casework involves paper depositions, the Western custom of cross-examining witnesses under oath before a judge is uncommon but, while American defendants lose their Fifth Amendment rights against self-incrimination if they testify, Chinese defendants may say what they wish in their defense or refuse to be cross examined, without prejudice. If the investigating magistrate decides that the defendant is guilty the case goes to trial, which is really a sentencing hearing, but even if a defendant confesses and wishes to end the matter, the magistrate must hold an open trial and ask the defendant to confirm his confession publicly.

Though lawyers’ reputation in Chinese society has always been poor, the profession was boosted in 2012 when Li Keqiang7, an expert on English common law, became Premier and, overnight, the Supreme Court’s internship program began attracting top students. Then President Xi suggested establishing independent judicial committees, including non-Party members, to select judges based on merit and professional track record and, by 2019, every province had an independent judicial committee to minimize local government interference, select and oversee the work of judges and prosecutors, and punish professional misconduct. Shanghai’s committee expelled a High Court prosecutor, two sub-prosecutors, the Vice President of the Provincial Supreme Court and a senior circuit court judge. Police, prosecutors and court officials are responsible for wrongful prosecutions until the day they die, and national appeals courts re-hear cases, overturn wrongful convictions, order restitution, and require lower courts to study their reversals.

The Supreme People’s Court’s website, with five billion visits, offers online courses on every element of the law, invites criticism of new laws, and provides an artificial intelligence interface to its six hundred thousand recorded trials. Its website invites citizens to email the Chief Justice, whose answers begin cheerily, “Hello! We received your question, and after consideration, we respond as follows…” and end with, “Thank you for your support of the work of the Supreme People’s Court!” Ultimately–since their ethical duty transcends their legal responsibility–the courts answer to the Party which, as arbiter of national ethics, prevents unethical and anti-democratic decisions8. As former Chief Justice Xiao Yang explained, “The power of the courts to adjudicate independently doesn't mean independence from the Party at all. On the contrary, it embodies a high degree of responsibility vis-à-vis the Party’s [dàtóng9] program.”

Though unarmed, police have powers their Western colleagues only dream of. Instead of removing miscreants from society they can issue temporary restraining orders and mandate home confinement, which gives them the opportunity to discuss solutions with their families. Convicted criminals–who can prosecute prison staff for breaching their rights–must receive humane levels of material comfort and dignity from arrest to release. Sentences are typically short, but prisoners must participate in career, legal, cultural, and moral counseling that focuses on the social consequences of their crimes. Even murderers are expected to repent, reform, and rejoin society.

Citizens can video police, who must publish the status of all arrestees online. TV programs regularly explain new laws and schools, offices, factories, mines and army units discuss concepts like the exclusion of illegally obtained evidence. After the success of a weekly TV show, I am a Barrister, the Legal Channel followed up with The Lawyers Are Here. Each episode introduces legal issues ranging from child custody to healthcare negligence and expert panels offer opinions and advise real litigants on air.

Online Trial Spots are reducing legal costs, promoting equitable outcomes and lightening the burden of enforcement. One app bundles free mediation, dispute settlement and legal aid and connects plaintiffs to thousands of lawyers, notaries and judicial appraisers. Another verifies plaintiffs’ and defendants’ IDs and combines face and speech recognition with electronic signatures, allowing them go to trial without leaving home. Using voice-to-text, it submits their files, transcribes their testimonies, and stores their case records in case of appeal. Beijing’s Internet Court provides artificial intelligence-based risk assessment as a public service and automatically generates legal documents, applies machine translation, and simplifies settlements through oral interaction with its knowledge base. In 2017 Hangzhou, home of Alibaba, launched the first cyber court exclusively for online e-commerce complaints, loan litigation, and copyright infringement. In its inaugural case, TikTok sued Baidu for ownership of user-generated video content.

With unarmed police, two percent of America’s legal professionals and one-fourth its per capita policing budget, China has the world’s lowest rates of imprisonment and re-offense. Crime remains low, trust is rising, and Beijingers no longer remove batteries from parked electric scooters. When Harvard’s Tony Saich10 surveyed them about their greatest worry, most Chinese ranked ‘Maintenance of Social Order’ highest and when he asked which government service pleased them most they chose ‘Maintenance of Social Order.’

____________________________________________________________________________

NOTES

1 Report, 18th Party Congress, November 8, 2012. Xi was quoting from Confucius’ Analects.

2 Xi stresses integrating law, virtue in state governance. Xinhua. 2016-12-10

3 The Chinese term for nation-state is ‘nation-family’ and most Chinese would take for granted that the nation-state is an extended family.

4 Failure to do so can bring consequences. In 2018, when Liu Zehnhua committed suicide after raping and murdering Li Mingzhu, the court ordered Liu’s family to pay the Li family one hundred thousand dollars for failing to socialize their son.

5 In addition to People’s Mediation conducted by grassroots community mediators, China employs Judicial Mediation conducted by judges, Administrative Mediation conducted by government officials, Arbitral Mediation conducted by arbitral administrative bodies, and Industry Mediation conducted by specific industrial associations.

6 Average Person Spends $250 Per Year on Legal Services. Jay Reeves | April 14, 2015. Lawyers Mutual

7 At Peking University Law School in 1978, Li translated Lord Denning’s “The Due Process of Law,” becoming so proficient in the language that he broke protocol and spoke in fluent English at a Hong Kong University event in 2011.

8 In 2010 the US Supreme Court ruled that corporations can spend unlimited money on elections because limiting corporations’ “independent political spending” violates their First Amendment right to free speech.

9 A dàtóng society is the Chinese Dream, which Confucian scholar Kang Youwei rendered thus: “Now to have states, families, and selves is to allow each individual to maintain a sphere of selfishness. This infracts utterly the Universal Principle (gongli) and impedes progress...The only [true way] is sharing the world in common by all (tienxia weigong) This is the way of the Great Community, dàtóng, which prevailed in the Age of Universal Peace. Commentary on Liyun.

10 How China’s citizens view the quality of governance under Xi Jinping. Tony Saich. Journal of Chinese Governance. Vol 1, 2016

Kenneth J. Hammond is Professor of History at New Mexico State University. Hammond was a student and Students for a Democratic Societyleader at Kent State University from 1967 to 1970. He later (1985) completed his degree in Political Science, then studied Modern Chinese language at the Beijing Foreign Languages Normal School in Beijing. Hammond received an M.A. in Regional Studies -East Asia(1989), and a Ph.D in History and East Asian Languages (1994) from Harvard University. In 2007, Hammond was appointed director of the Confucius Institute, a cultural initiative funded in part by Hanban on the NMSU campus that is dedicated to studying and publicizing China and Chinese culture. He is the editor of the journal Ming Studies.

Kenneth J. Hammond is Professor of History at New Mexico State University. Hammond was a student and Students for a Democratic Societyleader at Kent State University from 1967 to 1970. He later (1985) completed his degree in Political Science, then studied Modern Chinese language at the Beijing Foreign Languages Normal School in Beijing. Hammond received an M.A. in Regional Studies -East Asia(1989), and a Ph.D in History and East Asian Languages (1994) from Harvard University. In 2007, Hammond was appointed director of the Confucius Institute, a cultural initiative funded in part by Hanban on the NMSU campus that is dedicated to studying and publicizing China and Chinese culture. He is the editor of the journal Ming Studies.