Why are Western leaders gawd awful bad and China’s so darn competent?(Part II)

Jeff J. Brown

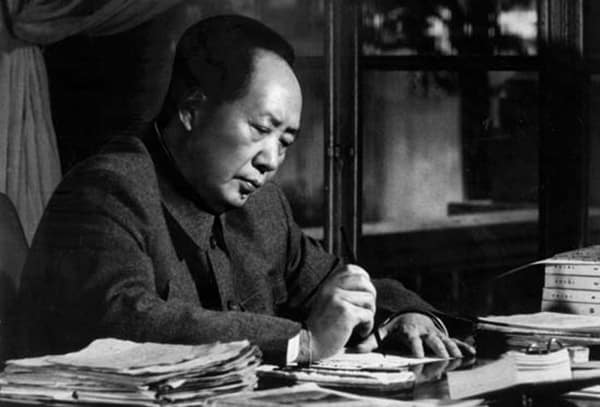

Iconic Mao Zedong silhouette badge. Below his bust is his famous mantra, “Serve the People”, written in his very recognizable calligraphic style. Many people do not notice, but on the back is the millennial governance motto, “Preserve the Peace”. Walking around the streets and in buildings here, you can see Mao’s famous calligraphic chant all over the place. Nothing has changed about governance in China for 5,000 years.

Live from the streets of China, Jeff

Downloadable SoundCloud podcast (also at the bottom of this page), YouTube video, as well as being syndicated on iTunes, Stitcher Radio, RUvid and Ivoox (links below),

<span

style="display: inline-block; width: 0px; overflow: hidden;

line-height: 0;" data-mce-type="bookmark"

class="mce_SELRES_start"></span>

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n the first part of this essay, I showed why Western leaders are generally so bad. The one sentence answer is they are almost always suborned to serve the interests of the 1% at the expense of the 99%. (The "1%"—meaning by that the ruling class billionaires— represents actually a lot more concentrated wealth, in the US and much of the "West" approximately 0.00001%).

There is a corollary explanation for this. European cultures and their spinoffs in the rest of Eurangloland, including Israel are founded on violence and theft. If you don’t believe this goes back to the Jewish Torah/Christian Old Testament, here is a quick review of Westerners’ predilection for killing, destroying, plundering first and asking questions later (http://skepticsannotatedbible.com/cruelty/long.html and http://commonsenseatheism.com/?p=21).

I created a comparative Excel table using Wikipedia’s pages on Conflicts in Europe, United States and China (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_conflicts_in_Europe, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_conflicts_in_the_United_States and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_conflicts_in_Asia#Mainland_China_(People’s_Republic_of_China). Europe’s list has 760 entries, the US’s 250 and China’s 315. Europe’s long list really starts in 1,100BC and does not include all of the genocidal horrors in the Torah/Old Testament before that. The US’s only starts in 1775, which is wishful propaganda. As Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz clearly proves in her book, A Native Peoples’ History of the United States, genocidal wars to exterminate the many millions of First Nations’ peoples started Day One with the colonial landing at Jamestown in 1607. and the killing has never stopped. China’s goes back to 2,500BC, so is over twice as long as Europe’s and compared to the US, almost ten times longer.

To sum up, Europe’s list of conflicts dates back 3,100 years and lists 760, the US’s starts 230 years ago, with 250 conflicts and China’s starts over 4,500 years ago and has 315. Interestingly, one-third of all China’s conflicts happened during its century of humiliation, 1839-1949, when the West terrorized and plundered the country, while addicting one-fourth of the people to opium, morphine and heroin.

Thus, while the West’s numbers are probably grossly understated, since over the centuries, it has committed thousands of government overthrows, invasions and occupations to protect colonial businesses around the world.

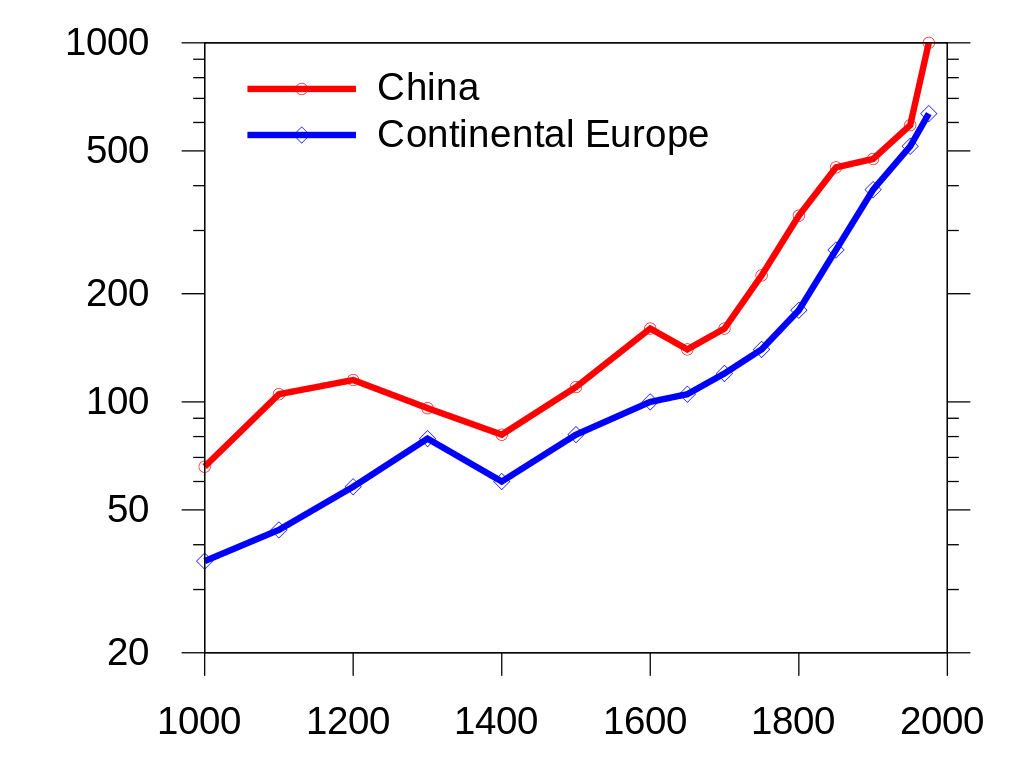

The above statistics speak for themselves. Eurangloland, including Israel conducts its business and trade using violence and expropriation. China, no. This contrast is even more remarkable, when looking at landmass and populations. When the Roman Empire was at its greatest expansion, 200AD, China had six times as much land and nine times as many people, but clearly was experiencing much less conflict, not nine times as much.

As the above chart shows, China has always had many more people than Europe, yet has lived with much less violence and plunder. This is because European cultures are founded on genocide, slavery and the violent plunder of other peoples’ natural resources. For 5,000 years, Chinese civilization has been based on agriculture, animal husbandry and mutually profitable cross border trade.

Proof of this is ample. The Chinese Asian land and African maritime Silk Roads predate Jesus Christ and they did not send out armies to rape and plunder their neighbors, like Alexander the Great, the Christian Crusades and onto modern colonialism and robber baron capitalism. The Chinese conducted state diplomacy, traded goods and technology.

If the Chinese had the same DNA for violence and theft that Westerners do, we’d all be speaking Mandarin today. The Chinese were sailing the high seas many centuries before the rest of the world and had Star Wars weapons compared to Europe and elsewhere, with advanced guns, powerful cannons, rocket propelled grenades, flame throwers, sea and land mines, not to mention chemical and biological bombs. They were so far ahead of the rest of the world in military and other technologies, that they could have easily crushed every city and people they came into contact with, like defenseless bugs. Yet, they fanned out across the planet and no one was ever attacked, unless the Chinese visitors were attacked first, which happened very rarely, given what they arrived with. They just wanted to do win-win business and exchange technology.

Westerners and Israelis can only think about other peoples in terms of war and exploitation. Since that is their world vision, they cannot assimilate the Chinese’s millennia of external non-violence and, Let’s do some business ethos. Cognitive dissonance overwhelms Euranglolanders when this is shown them and they sink into denial and self-serving mythology. They fall back on moral equivalence, Well, everybody else does it too. Not true, American Natives, Africans, and Asians (excepting the Christianized Genghis Khan family and Japan adopting the Western imperial playbook during its Meiji Restoration) have not blanketed the planet like killer locusts, devouring everything within their reach. Only Euranglolanders have done this and continue to do so.

This concept of Chinese governance and international trade goes back millennia, with the Confucist-Daoist-Buddhist concept of ren (忍), which means forbearance, relenting and retreating. You will never begin to understand how and why the Chinese live and work, until you wrap your head around ren. Ren is also the Chinese foundation for governing the country and leading the people. I highly recommend taking a few minutes to read/listen/watch these articles (https://chinarising.puntopress.com/2019/07/20/wests-hong-kong-color-revolution-still-making-a-mess-of-the-place-and-totally-backfiring-china-rising-radio-sinoland-190720/ and http://chinarising.puntopress.com/2017/11/10/all-the-chinese-people-want-is-respect-aretha-franklin-diplomacy-on-china-rising-radio-sinoland-171110/).

Great governments in China are the ones that have (and continue to) work for the 99%, first, second and third, maintaining social harmony, economic prosperity, securing the country’s borders and avoiding war at all cost. Avoiding war and running a lean administration meant being able to keep taxes low, in the form of grain sent to government storehouses for redistribution during droughts, so the masses had enough eat well and sell their surplus themselves to buy household goods.

In China’s pre-liberation era, this system was feudal, meaning wealthy land owners and bourgeois gentry had to be reigned in, to not demand too much grain for land use. Thus, China’s leaders were also expected to protect the 99% from local exploitation. This of course did not always happen. There were many regional conflicts and if national or local government authority weakened or was corrupt, the landlords could plunder the peasants, as well as become warlords in their areas.

Warlords on the loose were often a harbinger of a Chinese government that had lost its Heavenly Mandate. Democracy in Chinese is very responsive to the 99%’s needs. If the leaders can’t keep the peace, harmony and maintain the territorial integrity of the nation, then the masses have the right to “grab bamboo spears”, attack government centers and demand a new administration. This happened countless times over thousands of years at the local, provincial, regional and national level.

Maybe now you can have a little appreciation for why Chinese civilization has always had “big government”, from the dynastic center down to the local villages. No leaders can hope to govern effectively for the benefit of the 99% otherwise. This is why Western elites love “small government” neoliberalism, since it gives them a license to kill and plunder at will. What is important to understand, when comparing Chinese governance to Eurangloland’s is what the expectations were and are to this day. In China, it’s taking care of the little guy. In the West, it’s serving the wealthy elites, for them to accumulate more and more money property, possessions and power.

When Admiral Zheng He sailed around the world generations before Columbus and the Europeans, his massive flotilla reportedly had an anthology of China’s great books, totaling 200,000 pages, including the art of good governance. This was to show and tell with all the different governments and peoples they met, going from port to port.

China’s magnum opus for good governance comes from the 6th century AD, during the Tang Dynasty. A young emperor at the time was Taizong. Having gained the throne after his father, and having already learned to be a successful general, he realized that running a country and keeping the 99% safe and prosperous was a huge undertaking. Thus, he decided to collect all the ancient books on good governance and peacekeeping, going back to the beginnings of Chinese literature in 2,600BC and from them, generate an anthology of the best passages. The sources included 14,000 books and 89,000 written scrolls. The result was the Qunshu Zhiyao (群书治要), which can be translated as the Compilation of Books and Writings on Important Governing Principles. It totals 500,000 words and covers sixty five categories of good governance and peacekeeping.

In the preface of this 1,400 year-old collection, one of Emperor Taizong’s compiling advisors wrote,

When used in the present, (it) allows us to examine and learn from our ancient history; when passed down to our descendants,(it) will help them learn valuable lessons in life.

Taizong himself was ecstatic about the work, saying,

The collection has helped me learn from the ancients. When confronted with issues, I am very certain of knowing what to do. This is all due to your efforts, my advisors.

Above: stylistic rendition of Tang Emperor Taizong, showing his successful military past in the background and thereafter, his forward thinking good governance and peacekeeping in the foreground.

Of course, over five millennia of civilizational history, China has had its fair share of megalomaniacs, psychopaths, corrupted and incompetents in positions of power, both government and military. But, as the Qunshu Zhiyao instructs, the ideals of good governance and peacekeeping are all about social harmony, economic prosperity and avoiding war at all cost, so politicians and leaders of this stripe are the outliers, not the mainstream, as is the case in Eurangloland. Western elites work hard to put megalomaniacs, psychopaths, corrupt and incompetent people in positions of power, since these latter can be manipulated to serve the previous’ interests. Politicians who practice ren and strive for social harmony, economic prosperity and peacekeeping are Eurangloland’s worst enemies. To wit, China’s Xi Jinping, Russia’s Vladimir Putin, Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro, Iran’s Hassan Rouhani, DPRK’s Kim Jong-Un and every other socialist/anti-imperialist leader across the globe.

To learn more about why Chinese leaders are often so competent – yesterday, today and tomorrow – you can download below and read a book of excerpts from the Qunshu Zhiyao, put out for free by the Malaysian publishing house, Chung Hua Cultural Education Centre. Just glancing over a few of its 1,400-year-old section titles tells you that the people’s expectations of a Chinese leader are not what the 99% usually gets in the West,

Be careful of military actions

Be frugal and diligent

Be respectful of the Dao

Be sincere and trustworthy

Benevolence and righteousness

Caring about people

Character building

Correcting our own mistakes

Emulate good deeds

Exercising caution from beginning to end

Formation of cliques

Guard against greed

Heeding troubling signs

Human sentiments

Magnanimity

Paramount impartiality

Propriety and Music

Refrain from anger

Talents and virtues

Teach and transform

The livelihood of the people

Uphold integrity

Mao Zedong’s famous mottoes were,

Serve the People!

Preserve the Peace!

Mao did exactly that for one-fourth of the human race and was simply living up to the expectations that the Chinese 99% have had for their leaders, going back 5,000 years. It is still ongoing with Xi Jinping and every leader in between. Euranglolanders cannot count themselves so lucky in the quality of their leaders and integrity of their governance.

The Governing Principles of Ancient China book in downloadable PDF (click the link below):

The Governing Principles of Ancient China

Punto Press released China Rising - Capitalist Roads, Socialist Destinations (2016); and for Badak Merah, Jeff authored China Is Communist, Dammit! – Dawn of the Red Dynasty (2017).

Punto Press released China Rising - Capitalist Roads, Socialist Destinations (2016); and for Badak Merah, Jeff authored China Is Communist, Dammit! – Dawn of the Red Dynasty (2017).

Jeff can be reached at China Rising, jeff@brownlanglois.com, Facebook, Twitter and Wechat/Whatsapp: +86-13823544196.

• check this page on his special blog CHINA RISING RADIO SINOLAND

The battle against the Big Lie killing the world will not be won by you just reading this article. It will be won when you pass it on to at least 2 other people, requesting they do the same.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]f you find China Rising Radio Sinoland's work useful and appreciate its quality, please consider making a donation. Money is spent to pay for Internet costs, maintenance, the upgrade of our computer network, and development of the site.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]f you find China Rising Radio Sinoland's work useful and appreciate its quality, please consider making a donation. Money is spent to pay for Internet costs, maintenance, the upgrade of our computer network, and development of the site.

Just use the donation button below (yes, click on Sylvester the Kitty)

Just use the donation button below (yes, click on Sylvester the Kitty)

![]()

![]()

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

PREFATORY NOTE