By Joanne Laurier, wsws.org

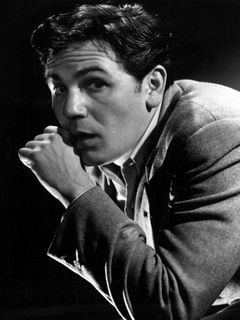

Garfield with Lana Turner, the doomed incandescent duo in Postman Rings Twice.

“Garfield was the darling of the romantic rebels, beautiful, enthusiastic, rich with the knowhow of street intelligence. He had passion and a lyrical sadness that was the essence of the role he created as it was created for him. The Group Theatre trained him; the movies made him; the Blacklist killed him…” wrote fellow blacklist victim and filmmaker Abraham Polonsky about actor John Garfield.

March 4 marked the centenary of film actor John Garfield’s birth in New York City. Garfield, from a working class background and identified with left-wing beliefs and causes, died at the age of 39, a victim of the anticommunist blacklist. One of the most charismatic figures in post-World War II American films, he made 35 films in his 13-year movie career.

It is the aim of this tribute to encourage readers to watch—or re-watch—Garfield’s best work, particularly a series of complicated, intriguing films he made in the late 1940s and early 1950s, including The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), Humoresque (1946), Body and Soul (1947), Force of Evil (1948) and The Breaking Point (1950). We would particularly urge a younger generation to make the effort to see these movies, even if that involves overcoming a prejudice against black-and-white films, because this period was one of the high points in the history of American cinema.

As Robert Nott details in his biography He Ran All the Way: The Life of John Garfield, the future actor was born Jacob Julius Garfinkle on March 4, 1913 into the poverty of New York’s Lower East Side. His parents were first-generation Americans of Ukrainian-Jewish peasant descent. His father David was a coat presser in the garment district, working 10 to 12 hours a day. Young Garfield began life in a cold water flat as a child of the slums.

Garfield’s mother died when he was seven, and he and his brother Max were sent to live with relatives in the tenements of the tough Brownsville section of Brooklyn. When his father remarried, the family relocated to New York’s West Bronx. Garfield would later recall that in his youth, he learned “all the meanness, all the toughness it’s possible for kids to acquire.”

It was at Public School 45 in the Bronx that Garfield was introduced to acting by the noted educator Angelo Patri. Garfield was later to say of Patri, “For reaching into the garbage pail and pulling me out, I owe him everything.” It is an indication of the cultural circumstances then prevailing that Garfield, still a teenager, was soon able to study with famed Russian actress Maria Ouspenskaya. She and other former members of the Moscow Art Theater promoted the Stanislavsky system of acting. Garfield made his Broadway debut in 1932, in a long-forgotten play that only ran two weeks.

The background to Garfield’s early acting career and the New York cultural scene of the time was the Great Depression, the growing radicalization of millions and the attractive force for many of the Soviet Union, still identified with the October Revolution of 1917. Whether Garfield ever joined the Communist Party or not, he traveled in its environs, like many of the leading film and theater artists of the time. The gravitation toward the left was a perfectly natural one, as Abe Polonsky (born in New York in 1910) explained in a 1996 interview with David Walsh: “I was born into the Depression … My father was a socialist. The house was full of socialists. The attitude in our family was: if you’re not smart enough to be a socialist, you’re not smart enough to live.”

During this period, the early 1930s, a friend from the Bronx, Clifford Odets, told Garfield about the work of a collective called the Group Theatre, whose leading lights were Lee Strasberg, Harold Clurman and Cheryl Crawford. Odets of course became one of the best known left-wing playwrights and screenwriters of the 1930s and 1940s.

By 1935, the Group was New York City’s most influential avant-garde ensemble, known for teaching Stanislavsky-inspired “Method” acting. Among its members were Luther and Stella Adler, Franchot Tone and Elia Kazan. When Odets’ Waiting for Lefty became a success, the Group then staged the playwright’s full-length drama, Awake and Sing. Odets first Broadway hit, Golden Boy, was written with Garfield in mind, but it would not be until near the end of his life that Garfield would perform the role of boxer Joe Bonaparte in a revival of the play in 1952.

In 1937, reportedly propelled in part by his inability to land the leading role in Golden Boy, Garfield went to Hollywood and signed a contract with Warner Bros. His dynamism in a supporting role in Michael Curtiz’s musical drama Four Daughters (1938), with Claude Rains and the Lane Sisters, immediately made its presence felt with critics and audiences. Garfield followed up with Daughters Courageous (1940) for Warners, also directed by Curtiz and starring Rains and the Lane Sisters, although the film is actually about a different family.

From his early days in Hollywood, Garfield had the opportunity to work with numerous talented and even pantheon directors, including Busby Berkeley—of all people—on the hardboiled They Made Me a Criminal (1939); William Dieterle on Juarez (1939), a drama of Mexico’s struggle for independence from foreign domination; Curtiz once again on The Sea Wolf (1941), based on the Jack London novel, with Edward G. Robinson as the Nietzschean monster, Captain “Wolf” Larsen; Anatole Litvak on Castle on the Hudson (1940), a prison drama, and Out of the Fog (1941); Victor Fleming on Tortilla Flat (1942), from the John Steinbeck novel; Howard Hawks—whom Garfield reportedly told that he had long been an admirer of the director’s Scarface (1932) with Paul Muni—on Air Force (1943); and Delmer Daves on Pride of the Marines (1945), in which Garfield played a blind war veteran.

Garfield’s movie career had a meteoric trajectory. His impact on audiences is hard to overestimate. Like James Cagney, he was a volcano of working class intensity and directness. And like Cagney, his rapid-fire delivery of lines expressed a life-and-death urgency about what he was trying to communicate. Not accidentally, Garfield was described as “the most democratic of star performers on the movie lots.”

Among the lesser known of Garfield films is Saturday’s Children (1940) , a Depression-era movie directed by Vincent Sherman for Warner Bros. Despite the movie’s predictable and slightly old-fashioned plot and feel, the heartfelt performances of both Garfield and Rains stand out as a protest against the injustices inflicted on the working poor, in which resides all of society’s talent, goodness and creativity.

Directed by Tay Garnett in 1946, The Postman Always Rings Twice —an adaptation of novelist James M. Cain’s popular work—is a classic film noir. Garfield, a drifter, finds employment at a rural diner. Lana Turner plays the older owner’s restless young wife. Both lead characters are ordinary people doomed by poverty, lack of opportunity and self-delusion. Critic Edmund Wilson termed Cain one of the “poets of the tabloid murder,” with his lacerating portraits of lower middle class individuals, “always treading the edge of the precipice.” Garfield and Turner are riveting as they fatalistically proceed to their demise.

That same year, Garfield starred in two striking works directed by Jean Negulesco: Nobody Lives Forever and Humoresque. The former features Garfield and the gifted Geraldine Fitzgerald in a melodrama about a con man returning from the war who goes straight after he falls in love with one of his marks, a rich widow. The latter film, from a script partly written by Odets, is about a boy from the slums who becomes a world-class violinist. The memorable movie also stars Joan Crawford and Oscar Levant, with Isaac Stern’s violin playing dubbed in. Garfield is explosive as a musician torn between his old proletarian world of loyal friends and family and a new one filled with spoiled, neurotic bloodsuckers.

Garfield reached his artistic zenith when he became an independent producer of his own films under the banner of Enterprise Productions. Among the most exceptional films Garfield made at that time were Body and Soul (1947), Force of Evil (1948) and The Breaking Point (1950).

Future filmmaker Robert Aldrich, assistant to director Robert Rossen on Body and Soul —about a prize fighter, again from the slums, who runs roughshod over those closest to him—said of Enterprise that it attracted the most talented artists who “tended to be more liberal [read “left wing”] than the untalented people, and because they were more liberal, they got caught up in social processes that had political manifestations, which later proved to be economically difficult to live with. In its search for talented and interesting people Enterprise hired a great many followers of that persuasion, and its pictures began to acquire more and more social content.”

In the Enterprise environment, which Aldrich described as a “really brilliant idea of a communal way to make films. It was a brand-new departure,” Garfield was able with his performances to tap into an unvarnished power. He forcefully dramatized the irreconcilable conflict between the exploiter and exploited, between the despicable means by which material wealth is acquired and the honest, decent qualities of the underdog. These are performances that spring from the deep, delivered by a performer hell-bent on unveiling the falsity of the American Dream.

One of Garfield’s most outstanding films, Body and Soul (directed by Robert Rossen, written by Polonsky), features a shattering relationship between Garfield’s Charley Davis, the boxer climbing the ladder of success with an unethical promoter, and his black trainer Ben, played by Canada Lee. Lee died shortly before he was to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). When the mob boss threatens Davis in the film’s final moments, after the boxer has crossed him, the latter famously shoots back, “What are you going to do, kill me? Everybody dies!”

Polonsky wrote and directed Force of Evil (1948) , a film intended as an indictment of dog-eat-dog American capitalism. It chronicles the rise and fall of a young syndicate lawyer, Joe Morse (Garfield), who earns his money through crime and corruption, and the suffering of others. Morse believes that “to go to great expense for something you want that’s natural. To reach out and take it—that’s human, that’s natural. But to get pleasure from not taking … don’t you see what a black thing that is for a man to do?”

Polonsky said of his film, which equates crime with business: “The numbers racket was a big thing in New York. Always. And New York was good because to me it was a wonderful metaphor for the whole capitalist system. That’s what the picture is about—the monopoly of power that people want. I call it my exposé of capitalism.”

Garfield in Force of Evil

Tony Williams, in his Body and Soul: The Cinematic Vision of Robert Aldrich, that unlike the case in Rossen’s film, “there are no real viable alternatives for him [Joe Morse in Force of Evil ] to consider because the omnipresent nature of the system renders them all unviable. Were this a Warner Bros. social consciousness gangster movie, Joe would see the light and join in his brother in a crusade against the racket. Fortunately, Polonsky recognized the illusionary aspects of a generic formula.” Williams later calls Force of Evil “a masterly cinematic experiment, the like of which would never be seen (or heard) again in American cinema.”

Like a good many other films that emerged from Communist Party-influenced artistic circles, Force of Evil suffers from a failure, so to speak, to entirely dissolve the politics in the poetry. The ideologically meaningful speeches, especially those delivered by Morse’s indignant and long-suffering brother Leo (Thomas Gomez), tend to be the least convincing moments in the movie.

One is most likely to remember some of the striking images—the shots of New York’s financial district, Morse’s endless descent “down and down” to find his brother’s corpse near the Hudson River (“It felt like I was going down to the bottom of the world”), as well as the sensual-suggestive scenes between Morse and Doris (Beatrice Pearson), a complicated young woman he falls for. Indeed, critic Andrew Sarris once noted that the Garfield-Pearson taxicab scene in Force of Evil “takes away some of the luster from [Elia] Kazan’s Brando-Steiger tour de force in On the Waterfront .”

Of the three film adaptations of Ernest Hemingway’s 1937 novel about rich and poor in America, To Have and Have Not, Michael Curtiz’s The Breaking Point (1950) is the finest, in my view. (And that is high praise, considering that one of the others is Hawks’ 1944 first-rate version with Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, which retained the novel’s title, if relatively little of its content.)

In Curtiz’s film, Harry Morgan (Garfield), the owner of a sport-fishing boat, faces an increasingly impossible financial situation. As a result, he is obliged to accept work with an oily, dishonest lawyer (played marvelously by Wallace Ford) smuggling illegal immigrants. That doesn’t work out, and Morgan comes under even more pressure. He then agrees to take a more dangerous assignment, transporting a gang of thieves who plan to rob a racetrack.

Meanwhile he divides his time and attention between his home, where his appealing wife Lucy (Phyllis Thaxter) pleads with him not to undertake anything illegal, and a local bar, where temptress Leona Charles (Patricia Neal) can be found.

In the final portion of The Breaking Point, Morgan’s black friend and right-hand man, Wesley Park (Juano Hernández), is cold-bloodedly murdered and thrown overboard by the crooks before the film climaxes in a shootout. In the devastating concluding scene, Wesley’s young son (played by Hernández’s real-life son) stands alone on the dock looking around for his father. In this brief sequence, Curtiz, like all great filmmakers, is able to identify and bring to the audience’s attention a tragedy that dwarfs the one that has befallen the movie’s central character.

John Berry’s He Ran All the Way, released in June 1951, in which Garfield plays a petty thief on the run from the police after a botched robbery, was the actor’s final movie role. In the film’s initial run, Berry and screenwriters Dalton Trumbo and Hugo Butler were uncredited because they had already fallen victim to the anti-communist blacklist.

John Garfield’s film career was destroyed in a matter of months and his life would end just a little over a year after his appearance before the House Un-American Activities Committee in April 1951. This was the height of the anti-communist hysteria in the US, the time of the Korean War and the trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg on charges of spying for the USSR.

Garfield was perhaps the best known and most successful actor to be totally blacklisted in the industry. His prominence, swagger and outspoken advocacy of various left-wing causes had long made him a bête noir of the extreme right, especially its anti-Semitic elements, who liked to point out Garfield’s birth name.

In his final year, the lack of film work debilitated him and although he refused to “name names,” he did present himself as an anti-communist, which further alienated him from his wife Roberta, who had been a Communist Party member. After his HUAC appearance, however, according to Garfield’s daughter Julie, the FBI called the actor in and asked him to confirm his wife’s involvement in the CP. She reported that her father responded with profanity and left. Julie also claimed that her mother believed studio executives had used Garfield as a scapegoat to take attention from others in Hollywood because he had “formed his own production company and they felt threatened by him.”

In an interview with the WSWS in May 1998, only 18 months before his own death, director John Berry—who emigrated to Europe after his blacklisting—commented: “Rumor had it that he [Garfield] was facing five years in the can if he didn’t give names. It’s easy to be heroic when you’re not facing that. It’s one hell of a choice. They would say to you, ‘Name names, we have them all, anyway.’ It’s a lie. People I met in the Resistance were told the same thing. ‘Just give one piece of information, give us a small piece.’ But it never stops. It was an abuse of power.

“We thought, at the time, to have won the war, to have fought for those correct causes…We thought there was going to be an expanding, a widening of horizons. There would be a much stronger sense of the people. America’s prosperity was so incredible. Two years later, everything was turned into its opposite.”

Berry told French filmmaker Bertrand Tavernier in an interview (included in Tavernier’s Amis Americains ) that HUAC confronted Garfield with evidence that he had attended a Communist Party youth meeting when he was 17. “They [the Committee members] wanted to break him. They didn’t succeed, but John was dying. According to what I was told, he lived under this threat, he couldn’t sleep any more, he drank a lot, he was worried, anguished. He had to appear again before the Committee to defend himself, and it was the morning he was scheduled to take the train for Washington that he cracked. His death was not an accident, it was provoked by this pressure they put on him.”

Additional hammer blows to Garfield’s psychological and physiological condition came in the form of his close friends Kazan and Odets turning informer—Kazan in April 1952 and Odets just days before Garfield’s death from coronary thrombosis on May 21, 1952.

About those acts of perfidy, Julie Garfield said: “Doctors have explanations for what causes death, but in my family we knew that it wasn’t precisely a heart attack that killed my father—it was more like an attack of the heart, by his own country and by his close friends, including those he most revered: the Kazans and the Odetses, the ones who betrayed their own kind to save their careers.”

John Garfield was the product of a working class community with a powerful socialist tradition. The best of his generation were influenced by the Russian Revolution and the Communist Party, whose degeneration under Stalinism tragically played a role in creating the predicament Garfield and others faced during the Hollywood witch-hunts.

One need only look at the list of performers and filmmakers with whom Garfield was associated to appreciate the immense radicalized cultural life of that period. It was a world of extreme want and considerable enlightenment.

Andrew Sarris, not one to approve of the “left” films of the late 1940s, commented profoundly about Garfield in “You Ain’t Heard Nothin’ Yet”: “From the beginning he projected a street-wise social consciousness … that made him a more poetically extroverted actor than the Method actors, notably Montgomery Clift, Marlon Brando, and James Dean, who followed him. Whereas they looked deep inside themselves for their demons, Garfield looked outside far and wide, at home and abroad, for the social injustices that afflicted humanity.”

Cagney, Robinson and Garfield, among others, elevated the presentation and presence of the working class in American films. They combined toughness with an intellectual sophistication and thoughtfulness—the street kid who was sensitive and generous of spirit. In his roles, Garfield had an anti-establishment commitment of a noble sort. His characters always made a quasi-cynical appraisal of the world, but they were far from cynical human beings. Their charm was irresistible in its lack of affectation and self-consciousness. Biographer Lawrence Swindell (in his Body and Soul ) suggests: “Garfield’s work was spontaneous, non-actory; it had abandon. He didn’t recite dialogue, he attacked it until it lost the quality of talk and took on the nature of speech. The screen actor had been the dialogue’s servant, but now Julie [John] had switched those roles”

Anyone interested in a revival of artistically serious and socially critical American filmmaking cannot afford to neglect John Garfield’s films.

__________________________________

We thank Joanne, and wsws.org, for this superb essay on a pivotal figure of American cinema. Garfield’s life and times pack lessons for today’s cinematic artists, many of which, like Kathryn Bigelow, are not content with cranking out mere escapism but enroll in active collaboration with a criminal status quo.