By now, Americans are virtually unshockable. When we hear of the latest workplace shooting, the latest school shooting, the latest loner who snapped and took others with him to his final rest, we are saddened, certainly, but not shocked. It has happened so often that we’ve long since lost count of the shooters and the victims, long since forgotten which towns bear the indelible marks of random violence. So it is difficult for us to understand the horror to which Americans were introduced by Charles Whitman on August 1, 1966. Until Whitman undertook his shooting spree in Austin, Texas, public space felt safe and most citizens were utterly convinced they were comfortably removed from brutality and terror. After August 1, 1966, things would never be the same.

Whitman’s story stands out for many reasons, not the least of which being that it features a co-star-the University of Texas Tower, from which he fired almost unimpeded for 96 minutes. The Tower afforded Whitman a nearly unassailable vantage point from which he could select and dispatch victims. It was as if it had been built for his purpose. In fact, in previous years Charlie had remarked offhandedly to various people that a sniper could do quite a bit of damage from the Tower.

The Tower is big-307 feet tall. It is a shorter building than the nearby State Capitol, but it stands taller as it is built on higher ground. It opened in 1937 and by 1966, it attracted roughly 20,000 visitors a year, most of whom wanted to take in the spectacular view of Austin from the 28th floor observation deck. The first death associated with the tower came during its construction; a worker slipped and fell twelve floors in 1935. There was another accidental death in 1950. There were also suicides in 1945, 1949 and 1961. Despite these tragedies the Tower stood as a beloved symbol of Texas pride and expansiveness, the figurative heart of the surrounding campus and city.

On the surface, Charles Whitman would have seemed as steady and upstanding as the Texas Tower itself. He came from a wealthy, prominent family in Lake Worth, Florida. He was a gifted student, an accomplished pianist, and an Eagle Scout. But the trappings of the Whitman home concealed turmoil. C.A. Whitman was a self-made man, a plumber who had worked and willed his way to the top of his profession and into polite society. He brooked no weakness in any of his three sons, and he ruled his home dictatorially. “I did on many occasions beat my wife,” he would later say, “but I loved her…I did and do have an awful temper, but my wife was awful stubborn….because of my temper, I knocked her around.” His discipline with his sons was equally harsh—he often employed belts, paddles and his fists to make sure they complied with his rules and met his expectations. Materially, though, C.A. Whitman’s family was amply provided for. C.A. and Margaret always drove late-model cars, and each of the boys was given guns, motorcycles, and other gifts C.A. thought fitting. Their home was the nicest in the neighborhood, with all the amenities and a swimming pool. But the luxuries did nothing to alleviate the troubles within the Whitman household.

In June of 1959, shortly before Charlie Whitman’s 18th birthday, tensions with his father came to a head. Charlie came home drunk from a night out with friends, whereupon C.A. beat him and threw him into the pool, where he nearly drowned. A few days later he applied for enlistment in the United States Marine Corps. He left for basic training on July 6, 1959.

Charlie spent the first part of his stint with the Marines at Guantanamo Naval Base in Cuba. He worked hard at being a good Marine, following orders dutifully and studying hard for his various examinations. He earned a Good Conduct Medal, the Marine Corps Expeditionary Medal, and a Sharpshooter’s Badge. Chillingly, the records of his scores on shooting tests show that he scored 215 out of 250 possible points, that he excelled at rapid fire from long distances, and that he seemed to be more accurate when shooting at moving targets. Captain Joseph Stanton, Executive Officer of the 2nd Marine Division remembered, “He was a good marine. I was impressed with him. I was certain he’d make a good citizen.”

It was important to Charlie that he be the best Marine he could be. After years of belittlement and abuse from his father, he was anxious to prove himself as a man. Every opportunity for advancement was a chance to distance himself from his brutal upbringing. The Naval Enlisted Science Education Program (NESEP) seemed tailor-made for the up-and-comer Charlie fancied himself to be. NESEP was a scholarship program designed to train engineers who would later become officers. Charlie took a competitive exam and then went before a selection committee which chose him for the prestigious award. He would be expected to earn an engineering degree at a selected college and follow that with Officer’s Candidate School. His tuition and books would be paid for by the Marine Corps. He would also receive an extra $250 a month.

Charlie was admitted to the University of Texas in Austin on September 15, 1961. After years of rigid discipline at home and regimented life in the Marines, he was suddenly free to use his time as he wished. Almost immediately he began to get into trouble. He and some friends were arrested for poaching deer. He accumulated gambling debts and refused to pay them, angering some dangerous characters in the process. His grades were unimpressive. He did manage some improvement after he married his girlfriend, Kathy Leissner, in August, 1962, but the Marine Corps was unforgiving of his previous behavior. His scholarship was withdrawn and he returned to active duty in February, 1963.

He was stationed at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina. After a year and a half of freedom, he found the discipline and structure of military life oppressive. His wife was back in Texas finishing her degree and he was lonely. He tried to recapture his scholarship but failed, and was informed that the time he’d spent in Austin did not count as active duty enlistment. He resented the Marine Corps and it showed in his behavior. In November 1963, he was court-martialed for gambling, usury and unauthorized possession of a non-military pistol. He had threatened a fellow soldier who had failed to repay a $30 loan with 50 percent interest. He was found guilty and sentenced to 30 days confinement and 90 days hard labor. A promotion he had received upon his return to active duty was stripped from him. Lance Corporal Whitman was once again Private Whitman, and he was desperate to be free of the Marine Corps. He turned to his father for help. C.A. Whitman had made connections in his years as a prominent businessman, and he set about trying to pull strings to get Charlie’s enlistment time reduced. Charlie’s stint was reduced by a year, and in December 1964, he was honorably discharged from the Marines.

Charlie returned to Austin with a fervent sense of purpose. His failure as a Marine and as a student embarrassed him, and he was determined to redeem himself. He changed his major from mechanical engineering to architectural engineering and began applying himself more vigilantly than he had in his first spell at the university. He took a job as a bill collector for the Standard Finance Company, then moved on to a teller position at Austin National Bank. In his spare time, he served as scoutmaster for Boy Scout Troop 5. He worked hard at being upstanding and admirable, yet constantly berated himself for not living up to his own expectations. His copious journals contain countless self-improvement schemes and lists of traits he felt he should develop. In the early period of his marriage, he had followed his father’s example and become violent with his wife. He was determined not to repeat this behavior and reminded himself in his journal of how a kind and caring husband should act. He seemed to have no inner foundation of morals on which to build his own character; his constant self-instruction was an attempt to impose such a structure from outside himself. A friend described him as, “like a computer. He would install his own values into a machine, then program the things he had to do, and out would come the results.” From time to time, though, his façade would crumble. He was subject to bouts of temper and frustration, which only served to further damage his self-respect.

Kathy Whitman

(Texas Dept of Public

Safety)

Kathy Whitman did the majority of the breadwinning in the Whitman household. Her job as a teacher at Lanier High School in Austin provided a salary and health insurance; Charlie’s income supplemented hers, but he was keenly aware that his wife earned more than he.

Furthermore, he continued to receive money and expensive gifts from his father. Charlie hated freeloaders, yet that was how he saw himself. He hated failure, yet he had failed to accomplish anything he had set out to do since he left home at 18. He saw being overweight as a sign of weakness, yet he was unable to keep himself as trim as he had been in the Marines. Outwardly, Charlie was diligent and conscientious, a devoted husband and a hard worker; inwardly, he seethed with self-hatred.

Kathy Whitman noticed her husband’s ever bleaker outlook and began to gently urge him to seek counseling. Meanwhile, C.A. and Margaret Whitman separated after another violent row. Margaret and Charlie’s brother Patrick moved to Austin in the spring of 1966. C.A. called ceaselessly, begging Margaret to return to him, but she refused. In May she filed for divorce. Charlie’s troubled family, it seemed, had followed him. In this place where he was determined to make a new start he was constantly reminded of his past. His depression and anxiety worsened, and Kathy finally persuaded him to see a doctor that spring.

Dr. Jan D. Cochrun prescribed Valium for Charlie and referred him to University Health Center Staff Psychiatrist Dr. Maurice Dean Heatly. Heatly found that Charlie “had something about him that suggested and expressed the all-American boy,” but that he “seemed to be oozing with hostility.” Charlie spoke mainly of his lack of achievement and his hatred of his father. At one point, he told Heatly that he had fantasized about “going up on the Tower with a deer rifle and shooting people.” Heatly was not disconcerted. Many of his patients had made references to the Tower, and Charlie showed no behavior patterns as of yet that indicated that he was serious. He had, in fact, been making such comments for years, and everyone dismissed them as nonsense. Heatly suggested that Charlie return a week later, and told him that he could call at any time. Charlie did not return, nor did he call.

In the summer of 1966, Charlie dutifully attended to his class work and his job as a research assistant with the help of the amphetamine Dexedrine. Sometimes he went for days without sleep, studying and attending to various projects. He was taking a very heavy course load, trying harder than ever to excel. But the drug made him inefficient. Even though he spent many hours working, he could not seem to accomplish what he wanted. As a result, his self-esteem suffered even more. Additionally, his father was still calling, trying to get Charlie to convince Margaret Whitman to return to him in Florida. Though friends and family generally agreed that Charlie was under strain and trying to do too much, no one noticed he was edging quietly toward violence. As the Texas summer heat intensified, Charlie became ever more consumed by his fantasies of killing.

Preparations

Charlie’s first concrete action toward the plan he’d been formulating came on July 31. That morning he bought a Bowie knife and binoculars at a surplus store, and canned meat at a 7-11. Afterwards, he picked up Kathy from her summer job as a telephone operator for Southwestern Bell. They went to a movie, and then joined Margaret Whitman for a late lunch at the cafeteria where she worked. Following lunch, they dropped in on their friends John and Fran Morgan. The Morgans found Charlie unusually quiet, but suspected no trouble. Kathy returned to Southwestern Bell for another shift at 6:00 p.m. Charlie went home alone. At 6:45 p.m,. he began typing a letter of explanation and farewell.

“I don’t quite understand what it is that compels me to type this letter,” he wrote. “Perhaps it is to leave some vague reason for the actions I have recently performed.” He went on to say he’d increasingly been a victim of “many unusual and irrational thoughts” and that his attempt to get help with his problems (the visit to Dr. Heatly) had failed. He expressed a wish that his body be autopsied after his death to see if there was a physical cause for his mental anguish. As he continued, he outlined his plan for the coming 24 hours. “It was after much thought that I decided to kill my wife, Kathy, tonight after I pick her up from work at the telephone company,” he revealed. “The prominent reason in my mind is that I truly do not consider this world worth living in, and am prepared to die, and I do not want to leave her to suffer alone in it.” He continued, “similar reasons provoked me to take my mother’s life also.”

Charlie’s typing was interrupted by a visit from Larry and Eileen Fuess, a couple with whom Charlie and Kathy were friends. The Fuesses found Charlie unusually calm, but happy. They chatted for a while. Charlie told stories, talked of buying land on Canyon Lake, and spoke very sentimentally of Kathy. Twice he said, “It’s a shame that she should have to work all day and then come home to…..” but didn’t finish the sentence. The three friends bought ice cream from a street vendor, and the Fuesses left around 8:30 p.m.

Presently, Charlie left the house to pick up Kathy. Her shift ended at 9:30, and they were probably back home by 9:45. Kathy chatted on the phone for a while, then Charlie called his mother, asking if he and Kathy could come over and enjoy the air conditioning at her apartment. But Kathy didn’t accompany him to his mother’s place. She went to bed, and Charlie left their house around midnight.

Margaret Whitman greeted her son in the lobby of her apartment building, The Penthouse. When they were inside apartment 505, Charlie attacked her. The exact circumstances are not known, but it seems that he choked Margaret from behind with a length of rubber hose until she was unconscious. He then stabbed her in the chest with a large hunting knife. There was also massive damage to the back of her head, but since no autopsy was performed, it is uncertain if the wound was inflicted with a gun or with a heavy object. Margaret Whitman was dead by 12:30 a.m., at which time Charlie sat down to write another letter of explanation. “I have just taken my mother’s life,” he wrote, “I am very upset over having done it…I am truly sorry that this is the only way I could see to relieve her sufferings but I think it was best.” He placed his mother’s body in bed and pulled up the covers, then composed another note, this one designed to delay the discovery of what he’d done. He posted this one, intended for the building houseman, on the door of apartment 505. It read, “Roy, I don’t have to be to work today and I was up late last night. I would like to get some rest. Please do not disturb me. Thank you. Mrs. Whitman.”

Charlie left The Penthouse at about 1:30 a.m. but quickly returned saying he was Mrs. Whitman’s son and needed to get into her apartment to get a prescription he’d promised to fill for his mother. Probably, he had forgotten a bottle of Dexedrine, which he would need in the coming hours. The doorman let him into the apartment, and he returned in about five minutes with a pill bottle. He left The Penthouse for good around 2:00 a.m.

Kathy Whitman lay in bed asleep when Charlie returned home. Quickly and quietly, he pulled back the bedding and stabbed her five times in the chest. She probably never awoke. He then turned his attention to the letter he’d been typing the previous evening when the Fuesses had visited. “3:00 a.m.,” he scrawled on the page in blue ink, “Both dead.” With his pen he continued the explanation of his crimes, placing the blame for everything on his father and trying to make sense of the twisted morality that had brought him to murder. “I imagine it appears that I bruttaly [sic] kill [sic] both of my loved ones,” he wrote. “I was only trying to do a quick through [sic] job.” He wrote a few more notes, one to each of his brothers and one to his father. He left instructions that the film in his cameras be developed, and that his and Kathy’s dog be given to her parents. For a little while he looked back in his diaries, highlighting entries where he had extolled his wife’s virtues in years past. Then he set about preparations for the killing spree which would follow in a few hours.

Ready for Battle

(Austin Police Department)

In his old Marine footlocker Charlie packed an array of supplies. He brought a radio, 3 gallons of water, gasoline, a notebook and pen, a compass, a hatchet and hammer, food, two knives, a flashlight and batteries, and various other implements which made it clear he was prepared for a lengthy standoff. Additionally, he packed guns—a 35 caliber Remington rifle, a 6mm Remington rifle with a scope, a 357 Magnum Smith & Wesson revolver, a 9mm Luger pistol, and a Galesi-Brescia pistol. Later that morning he would buy two more weapons, a 30 caliber M-1 carbine and a 12-gauge shotgun. As he packed he refined his plan. At 5:45 a.m. he called Kathy’s supervisor at Southwestern Bell and told her his wife was sick and wouldn’t be reporting to work that day.

Charlie spent the morning accumulating more supplies. At around 7:15, he went to Austin Rental Company and rented a two-wheeled dolly to help him transport the heavy, unwieldy footlocker. He cashed checks amounting to $250 at the Austin National Bank, and bought guns and ammunition at Davis Hardware, Chuck’s Gun Shop, and Sears. Arriving home again at around 10:30 he called his mother’s employer and said she was ill and wouldn’t be coming to work that day. Then he took his new shotgun out to the garage and sawed off part of the barrel and the stock. At around 11:00 a.m. he put on blue coveralls over his clothes, trundled his footlocker to the car, and headed for campus.

At 11:30 a.m. Charlie arrived at a security checkpoint on the edge of campus. His job as a research assistant had provided him with a Carrier Identification Card, which was issued to those with a need to deliver large items onto the campus. He told Jack Rodman, the guard at the checkpoint, that he would be unloading equipment at the Experimental Science Building and that he needed a loading zone permit. Rodman issued him a forty-minute permit. By 11:35 Charlie had parked, unloaded his gear and entered the Tower. With his coveralls and dolly he attracted no undue attention—he looked like a janitor or maintenance man. He took an elevator up to the 27th floor, and then dragged the dolly and footlocker up three short flights of steps.

Edna Townsley was the receptionist on duty to supervise the 28th floor observation deck that morning. Her shift was to end at noon. Charlie hit her on the back of the head, probably with the butt of one of his rifles. He hit her again after she fell, then dragged her across the room and behind a couch. She was still alive, but would die in a few hours. At around 11:50, Cheryl Botts and Don Walden entered the reception area from the observation deck and found Charlie leaning over the couch, holding two guns. They greeted him, and though they found him strange and noticed some “stuff” on the floor (Edna Townsley’s blood), they were not immediately alarmed. Charlie watched them board the elevator, which took them to safety.

Meanwhile, M.J and Mary Gabour, their two sons, and William and Marguerite Lamport were headed up the steps from the 27th floor. They found the door barricaded by a desk. Mark and Mike Gabour pushed the desk away and leaned in the door to see what was going on. Suddenly Charlie rushed at them, spraying them with pellets from his sawed-off shotgun. Mark died instantly. Charlie fired down the stairway at least three more times. Marguerite Lamport was killed; Mary Gabour was critically wounded, as was her son Mike. They would lay where they fell for more than an hour. William Lamport and M.J. Gabour ran for help.

From the Tower

View from Texas Tower

(Austin Police Department)

On the lower floors of the Tower the alarm spread. People began barricading themselves into classrooms and offices. On the observation deck, Charlie unpacked his array of supplies and his guns. He wedged the door to the deck shut with the dolly and quickly set about firing. Turning his attention to the area of campus known as the South Mall, he began with his most accurate weapon, the scoped 6mm rifle. His first target was Claire Wilson, a heavily pregnant eighteen-year-old. The bullet pierced her abdomen and fractured the skull of the baby she carried, killing it. When she cried out, an acquaintance, Thomas Eckman turned and asked her what was wrong. Just then he was hit in the chest. He fell dead across his wounded girl. Nearby, Dr. Robert Hamilton Boyer, a visiting physics professor, took a bullet to the lower back. He died quickly.

To the east of the Tower at the Computation Center, Thomas Ashton, a Peace Corps trainee, was shot in the chest. He died later at Brackenridge hospital. As others in areas around the Tower began falling, those in surrounding buildings began to take notice. Wounded victims lay helpless, pinned down in the 95+ degree heat and fearful of being shot again. At about noon, University Police arrived at the Tower and proceeded to the 27th floor, where they discovered the Gabour/Lamport party. An order was given to secure the exits and shut off the elevators. It was not yet clear how many shooters there were, but from the number of calls that were coming in to both the Austin Police and the University Police, it seemed there must be an army atop the Tower.

Charlie was still moving about the observation deck unhindered, and turned his attention westward, toward Guadalupe Street. Known as the Drag, the busy street was lined with businesses and formed the western boundary of the UT campus. Initially, people on Guadalupe Street thought the echoing gunshots were part of a college prank. Then Alex Hernandez, a newsboy on a bicycle, fell wounded. Seventeen-year-old Karen Griffin fell next, and would die a week later. Thomas Karr, who had probably turned to render aid to Griffin, was then shot in the back. He died an hour later. Those inside Guadalupe Street businesses huddled together away from windows.

Austin Police were arriving on campus and trying to make their way to the Tower. Officers Jerry Culp and Billy Speed were huddled, with others, under a statue south of the Tower, trying to figure their next move. Charlie shot Billy Speed through a six-inch space between two balusters, which were part of a rail that surrounded the statue. Though Speed’s wound looked superficial to those around him, it was in fact grave. He was dying.

Back on the Drag, the carnage continued. Harry Walchuk, a thirty-eight-year-old doctoral student and father of six was exiting a newsstand when a bullet entered his chest. He died at the scene. Nearby, high-school students Paul Sonntag, Claudia Rutt and Carla Sue Wheeler dove for cover behind a construction barricade. As Paul peered out from behind the barricade to see what was happening, Charlie shot him through his open mouth. He was killed instantly. Another shot hit Claudia Rutt, who died later at Brackenridge Hospital.

By now word of what was happening had spread, and police began returning fire toward the Tower, trying to pick off Charlie as he rose up over the parapet to take aim. Citizens went home and got their own guns, and hundreds of shots chipped away at the Tower in the next hour. Charlie began shooting through the rainspouts on each side of the building, making himself virtually impossible to hit. He switched guns from time to time. The greater part of his killing had been done in his first twenty minutes on the observation deck, but he was not finished. Over 500 yards to the South, city electricians Solon McCown and Roy Dell Schmidt parked their truck and joined a group of reporters and spectators. They huddled behind cars for safety. Schmidt, probably thinking that they were out of range, stood up. He was hit in the abdomen, and was dead ten minutes later.

As more victims fell, police officers made their various ways to the Tower. Austin Police Officers Jerry Day, Houston McCoy, and Ramiro Martinez, Department of Public Safety Officer W.A. Cowan, civilian Allen Crum and others converged on the 27th floor. They cleared the floor and brought down Mary and Mike Gabour, who had lain critically wounded in a deep pool of blood for over an hour. Martinez and Crum moved carefully up the steps and into the reception area. McCoy and Day soon followed. There was no definite plan of action; each man had to improvise as the situation developed. From inside the reception area, they could cover windows on the south, southwest, and west sides of the Tower. Martinez tried the door to the observation deck, but found it had been wedged shut. He kicked the door until the dolly fell away, freeing the door. The men waited and watched the windows.

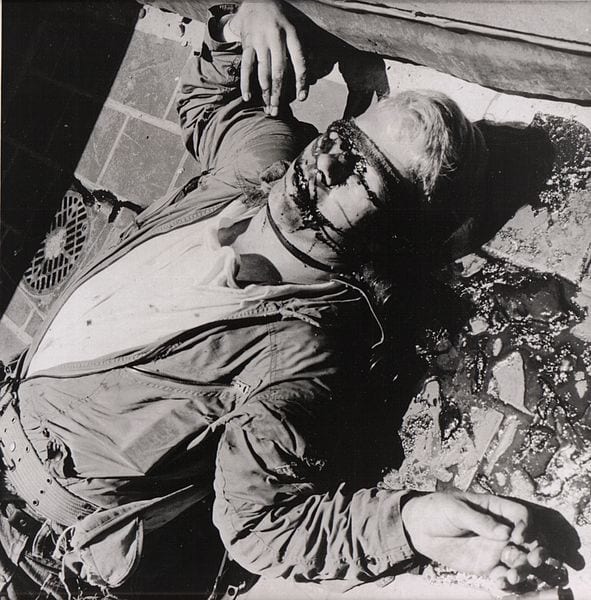

Charlie Whitman dead

(Austin Police Department)

Ramirez emerged onto the deck, and began crawling toward the northwest corner, where the shots seemed to be coming from. McCoy followed, while Crum and Day guarded the door. As Charlie tried to change position, Crum misfired his gun, sending him back to the northwest corner. There he sat with his back against the north wall, aiming his carbine toward the south, from whence Crum’s shot had come. Martinez and McCoy continued their slow crawl, friendly fire from the ground zinging around them. When Martinez reached the northeast corner, he rounded it and began firing his .38. Charlie tried to return fire but could not bring his weapon around in time. McCoy fired his shotgun twice at Charlie’s head, knocking him to the floor. Martinez then grabbed McCoy’s gun and ran toward Charlie’s twitching body, firing into it point blank. At 1:24 p.m. Charlie was dead.

Aftermath

Charlie had killed fourteen people and injured dozens more in a little over ninety minutes. Soon, Charlie Whitman’s name was being broadcast nationwide in television and radio news bulletins. In Needville, Texas, Kathy Whitman’s father heard his son-in-law’s name on the radio. Concerned for his daughter, he contacted Austin police. Kathy’s friends were calling, too, expressing concern and offering support. A car was sent to the Whitman’s Jewell Street home. Peering through a window, Officers Donald Kidd and Bolton Gregory saw Kathy’s body lying in bed. They entered the house through the window and found that she had been dead for some time. They also found Charlie’s notes. “Similar reasons provoked me to take my mother’s life also,” one read. Arriving at the Penthouse at around 3:00 p.m., police found the body of Margaret Whitman.

It soon became known that Charlie had sought the help of Dr. Heatly some months before, and Heatly released all his records regarding him to the public. Because Charlie had told Heatly of his fantasy of killing people from the tower during his one appointment, Heatly was suddenly under intense scrutiny. He was never found responsible in any way for the killings, however. The general consensus was that he’d done the best he could with the information he was given by Charlie. Nothing else about Charlie suggested that he would do what he did, so Heatly did not consider him a threat to himself or others.

When Charlie’s body was autopsied doctors discovered a small tumor in his brain. Some of his friends and family have seized upon this as the cause of his actions, but experts concur that this is doubtful. Charlie was buried in Florida beside his mother. As he was an ex-Marine, an American flag covered his coffin. Kathy Whitman was buried in her hometown of Needville, Texas.

At the Texas Tower the observation deck remained open for several years. The University spent $5000 repairing bullet holes in 1967. There were suicides, though, four of them in the years between 1968 and the closing of the deck in 1974. In 1976 the University of Texas Regents declared the deck permanently closed, and so it remained for over twenty years.

In October, 1998, University of Texas President Larry Faulkner announced plans to reopen the observation deck. He asked for the support of the University Regents in making the Tower a positive symbol of Texas pride once again. The Regents approved his plan, and on September 15, 1999 (the school’s 116th anniversary) the deck was reopened. There are security guards on the ground floor of the Tower and on the deck itself, which is surrounded by a stainless steel lattice to prevent suicides and falls. Visitors can once again enjoy the panoramic view from the Tower, but must pass through a metal detector to gain entry. The ghost of Charlie Whitman is, for the most part, exorcised. Yet the security precautions remind visitors that safety can only be ensured through hyper-vigilance.

There was a time when things weren’t like that. Charlie Whitman ended it for good.

Bibliography

Fox, James Alan and Jack Levin, Mass Murder and Serial Killing Exposed. Dell Publishing, 1996.

Lane, Brian and Wilfred Gregg, The Encyclopedia of Mass Murder. London: Headline Book Publishing, 1994.

Lavergne, Gary M., A Sniper in the Tower: The True Story of the Texas Tower Massacre. Bantam, 1997.

Newton, Michael, Mass Murder: An Annotated Bibliography. New York: Garland, 1988.

Steiger, Brad, The Mass Murderer. New York: Award Books, 1967.

Contemporary accounts may also be found in archives of these Texas newspapers: Dallas Morning News and the Austin American-Statesman