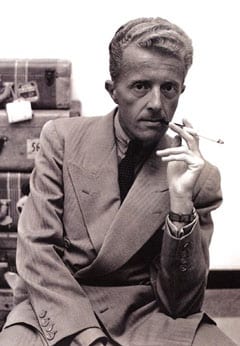

Stranger in a Strange Land: Notes, anecdotes, and memories of a weeklong interview with Paul Bowles in Tangier, Morocco

4586

When the first stories of Paul Bowles appeared in New York at the end of the 1930s critics noted the emergence of a remarkable new talent. Subsequently Bowles was to make his reputation on only a handful of books: four novels and five collections of stories. But what novels and what stories! Stories that Gore Vidal considers “among the best ever written by an American, with few equals in the 20th century – even though he is odd-man out for American academics because he writes as if Moby Dick never existed”. Likewise his friend of many years Tennessee Williams claimed that Bowles was a better writer than Hemingway and Faulkner.

When the first stories of Paul Bowles appeared in New York at the end of the 1930s critics noted the emergence of a remarkable new talent. Subsequently Bowles was to make his reputation on only a handful of books: four novels and five collections of stories. But what novels and what stories! Stories that Gore Vidal considers “among the best ever written by an American, with few equals in the 20th century – even though he is odd-man out for American academics because he writes as if Moby Dick never existed”. Likewise his friend of many years Tennessee Williams claimed that Bowles was a better writer than Hemingway and Faulkner.

I had the good fortune to meet Paul Bowles in a cold, rainy winter in the middle 1980s in Tangier. I had just read his novels “Under The Sheltering Sky” and “Let It Come Down” and his collection of stories in “The Delicate Prey” and was already a convert to his works. After an exchange of several letters to establish the timing – for years he had no phone, no fax or such, only a post box at Tanger Socco - I spent a week in Tangier for an extended interview with the mystical cult figure.

I was as excited about meeting him as the many others who traveled to Tangier had been during the 1960s. However by the 1980s figures like Allan Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Truman Capote, Jean Genet and the Rolling Stones no longer crowded the Moroccan scene. Young people no longer made the pilgrimage to exotic Tangier to search for the strange man who lived in quiet exile among his Moroccan friends. The Tangier craze was over.

By then Bowles had been living in Tangier since 1947, the last 30 years in the same apartment just opposite the residence of the American Consulate on the hill of Marshan looking over the old town. He had suggested in his last letter that I drop by each afternoon, after he had finished his day’s work: he was then transcribing a group of his early songs for publishing in the United States.

When I arrived on the first afternoon at around six the tape of a piece for oboe by his friend Aaron Copeland was playing. Paul Bowles was waiting at the door of his fourth-floor apartment. A fire was blazing, the unpretentious Moroccan-European salon inviting. Beguilingly the elegant maestro did not appear mysterious. His warmth and simplicity contrasted with his exotic reputation and the unreal world of his art. It was the aura around him that was mysterious, not he the person. In the United States he was considered mysterious chiefly because little was known about him since he lived his life abroad and wrote little about the American experience.

My host first proposed a cup of tea, only to discover he had no cooking gas. But in that moment his friend the Moroccan writer Mohammed Mrabet arrived, put in a full bottle of gas, and water was soon boiling. His Spanish speaking chauffeur then walked in and took a seat along the wall as if it were his assigned place. He was followed by two servants who set in cleaning rather ineffectually. Paul blithely didn’t seem to care.

While we were drinking tea and smoking kif - fresh kif-filled cigarettes were always drying by the fireplace as every afternoon in the Bowles household – the door banged open. Another Bowles literary discovery entered, Mohammed Choukhri, whose stories like those of Mrabet have been published in various languages. Choukhri presented Bowles with his latest essay on Jean Genet, which he on the spot dedicated to his friend, drank a cup of tea, smoked a kif cigarette, and hurriedly left.

Unexpected entertainment was then offered by a “jilala” musician, the quaspah player, Abdalmalek, an illiterate for whom Bowles had promised to write a letter. Bowles explained to me that when a sick or depressed Moroccan says “I think I need to dance,” it means he needs “jilala” therapy. Abdalmalek provides it. His music-therapy group plays the flute-like quaspah, bendir drums and bronze castanets called quarquaba until the frenetically dancing patient falls into a trance and leaves his body so that his saint can enter and clean house. Scenes like that appear not infrequently in Bowles literature.

“Probably no worse than many other treatments,” Bowles commented at the end of the impromptu 15-minute concert.

I never understood if Bowles had staged this Moroccan theater to impress the visiting journalist. I still doubt it.

Paul Bowles went to Morocco the first time in 1931, on the recommendation of his new friend, Gertrude Stein. “I had spent that spring in Berlin studying music with Aaron Copeland,” he recalled. “In Paris I told Gertrude that I planned to pass the summer in Villefranche. She found that idea frankly absurd.

Alice Toklas said: ‘Tangier!’ And Gertrude said: ‘That’s the right place.’ So Aaron and I came here together and rented a house. That summer he worked on his “Short Symphony” and I composed my first piece – “Sonata For Oboe and Clarinette” - that was played that winter in London.”

If that part of his life is often forgotten by his literary admirers, music was always important for Bowles. Yet contrary to some critics who noted the influence of music on his literature - the French critic, Marc Saporta, mentions the influence of American music forms like jazz and spirituals - Bowles said that he never felt that.

“I don’t have such highfaluting ideas. I just try to write as simply and clearly as possible. I’m not thinking about rhythm or music. I just try to get it into proper English. French critics haven’t a clue,” he added with a playful smile. “The French can’t play my music either.”

Nonetheless, during the 30s and 40s and occasionally afterwards Bowles was to compose a lot of music. Just to get some of this on the record: Bowles did the music for Tennessee Williams’ “The Glass Menagerie,” “Sweet Bird of Youth,” “Summer and Smoke,” and “The Milkman Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore,” for William Saroyan’s “Love’s Old Sweet Story,” Orson Welle’s “Dr. Faust” and others, for Arthur Koestler’s “Twilight Bar,” for Jose Ferrer’s film “Cyrano de Bergerac.” He composed a Mexican ballet and “Yankee Clipper” for the American Ballet Theater, an opera based on Garcia Lorca’s “Asi Pasen Cinco Anos” [1943] directed by Leonard Bernstein in New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and an opera, “Yerma” [1958]. His compositions were performed in that period at Lincoln Center, which was to be his last visit to the United States.

[dropcap]L[/dropcap]ike a character from a classical novel, his was a precocious biography. He was 21 on that first visit to Tangier but he had already been exposed to the Old World two years earlier. “I then thought Paris was the center of the world and I wanted to be there. College in America was boring. One way or another I had to get out. Since I was under age and my parents refused to sign for my passport, I got one under false pretenses and shipped out to France in 1929. I worked in Paris as a telephonist and the only people I met were the surrealist Tristan Tzara and his wife….I was impressed by his wonderful collection of African art.”

The die was cast. Music studies with Copeland in New York and Berlin, with Nadia Boulanger in Paris. Young Bowles had already frequented an art school in New York and written poetry in college. “I knew I wanted to be in the arts but I didn’t know in which art.”

And in fact, until 1945, music was the chief field of the future writer, precisely in the period when critics were saying that music and literature should be combined. Later Gore Vidal was to see that combination of arts in Bowles’ stories as “something most writers don’t have, the result of which are his disturbing stories like nothing in English literature.”

In those years Paul Bowles remained the inveterate traveler – North Africa, Latin America, Asia – until his final escape in 1947 when he returned for good to his beloved Morocco. He went back to Tangier with a literary reputation. He was a writer. Three of his first stories in particular had caused that stir in the New York literary world – “Pages From A Cold Point,” “The Delicate Prey” and “A Distant Episode” – which proposed one of his main themes: how inhabitants of alien cultures regard creatures of the civilized world. In those stories he tells Poe-like stories of horror, told so gently however that you hardly realize the horror.

When I met him in Tangier, Paul Bowles was no guru. I didn’t think of him that way. It was more a question of involvement. And of a man torn between diverse worlds. He helped his friends – “I can never get enough of them,” he said – and they helped him to bridge the gap between those worlds. Involvement with Mrabet was a long-standing one. Bowles translated the Moroccan writer’s first collection of stories, “Love With A Few Hairs” [1968] and helped him with the six subsequent books. Mrabet spent much time in Bowles’ apartment where he had his work desk.

Another evening: from downtown the walk uphill along the Boulevards Mohammed V Pasteur to the Marshan became familiar as was the warmth chez Bowles. The same dogs were always barking opposite his house. “Careful of those dogs,” he often warned me, “Packs of them right here in town.” When I asked him about the presence of dogs in his works he explained that he’d had a rabies scare after one bit him.

The fire was right, the teapot full and a row of kif cigarettes ready on the hearth when Bowles began recalling the old days in Tangier. “Morocco was a magic land when I first came. But it had changed radically when I returned in the 40s. It had become very Europeanized. After the war artists came here because of the monetary advantages and the cheap life.

“Tennessee Williams, Jack Kerouac, Gregory Corso, Alan Sillitoe, Cecil Beaton all passed through post-war Tangier; yet, there was never a real Tangier group. It was a fluid affair, with much coming and going. I was the only constant and I simply observed that movement. I was never a beat poet as some critics believe. I never felt close to Kerouac. I saw that group in New York and they came here for visits and I once took Allan Ginsberg to Marrakech but that doesn’t make me a beat poet. I knew them personally but I was not associated with the movement.”

Bowles seemed to enjoy reminiscing about old friends and that fantastic Tangier period that still has a limited literature: “Tennessee had lent his name to be used on the stationery of some ‘red network’ organizations and Senator McCarthy was breathing on his neck. In December of 1949 his agent asked me to get him out of the country, so we came here. He brought his car and we traveled to Fez and to south Morocco before he went on to Rome. He returned here many times though. You know, Tennessee was always rootless, he didn’t belong anywhere and had to move about. But he wouldn’t travel alone. Unlike me, the only good way to travel is alone.

“Then there was Daisy Valverde!” - a character in his novel about Tangier in the 1950s, Let It Come Down. “Daisy was mad. And very rich. Her wild parties were famous all over Europe. For one party she installed a whole Berber tribe in the ballroom and an entire village on the roof. After 1965 the hippies arrived! They came chiefly to smoke kif - or to look for LSD. Marrakech was the big attraction. They were romantics and felt at one with Moroccans … but they didn’t really know anything about them.”

Let It Come Down is Bowles’ most existentialist novel. A young American swept up in that Tangier life is attempting to establish his real identity in a world he sees as made of winners and losers. Alienated, with no character, no authority, no volition, he is a born loser. He commits a murder and that, ironically, is by accident, not by choice. High as a kite on majoun and kif, he confuses the ear of his sleeping friend with a banging door and drives a nail into it.

“That really happened in France,” Bowles said. “Sounded like a good book ending. Yes, I’m an existentialist, but not of the Sartrian type. [He by the way was the translator of Sartre’s play, “Huis Clos,” which he entitled “No Exit,” Daniel Halpern reports because of that phrase written over a subway gate that blocked his way.] I’m closer perhaps to Camus. I liked “L’Etranger.” I believe that that which is to happen will happen. In the early years I found it hard to write fiction because I couldn’t identify with the motivation of human beings. But then I don’t see man as naturally isolated, not any more than he wants to be.”

Yet, despite the daily visitors to his apartment that week, I thought of him as isolated. A hermit. In a permanent, self-imposed exile. He didn’t travel any more. He said that he only liked to travel with huge amounts of luggage, impossible today. So why move?

During those days I kept wondering where his ideas came from. Was he even an American writer? Or simply a writer who by chance wrote in English? The only thing he wrote about America was in his autobiography.

“Yes, I’m an American writer,” he claimed. “I loved the New York of the 1930s, until the FBI and later McCarthy began pestering me about my 20-month stay in the Communist Party in 1938-39. I always wanted freedom … chiefly freedom from my parents. Like many things in my life, I joined the Communist Party to spite my parents. That was the worst thing I could have done to them, except go to jail! I was never a Marxist. It was all a personal matter. No, I’m not de-Americanized. I’m delighted to be an American. Still I don’t write about American themes. What I remember of America is of three decades ago. But I can write about expatriated Americans because they don’t change much. Anyway I’ve never thought autobiographical material proper for fiction! My idea is to write about things I’ve never experienced.”

“Yes, I’m an American writer,” he claimed. “I loved the New York of the 1930s, until the FBI and later McCarthy began pestering me about my 20-month stay in the Communist Party in 1938-39. I always wanted freedom … chiefly freedom from my parents. Like many things in my life, I joined the Communist Party to spite my parents. That was the worst thing I could have done to them, except go to jail! I was never a Marxist. It was all a personal matter. No, I’m not de-Americanized. I’m delighted to be an American. Still I don’t write about American themes. What I remember of America is of three decades ago. But I can write about expatriated Americans because they don’t change much. Anyway I’ve never thought autobiographical material proper for fiction! My idea is to write about things I’ve never experienced.”

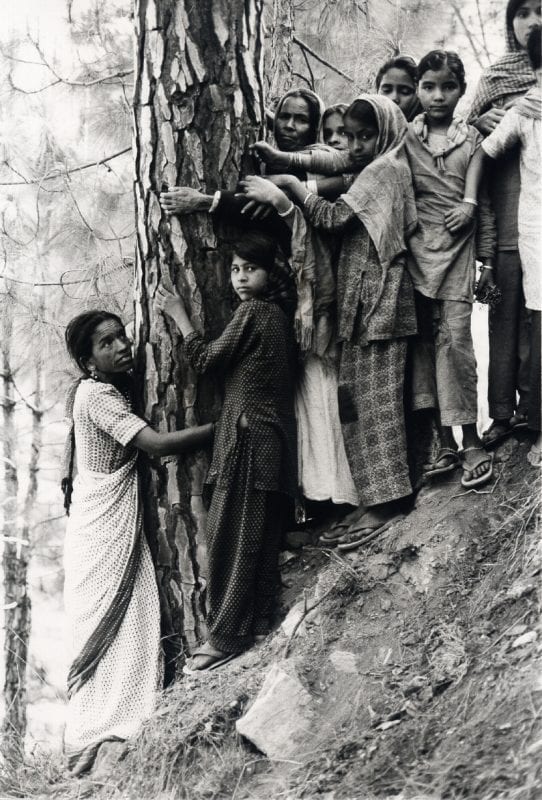

The Bowles artistic world is thus non-American. Alien. The setting is primitive, in the jungle or in the desert or on the edge of Europe. His tension results from the clash between civilized man and an alien environment. The Westerner is inevitably defeated by primitive man. For Bowles, modern man is lost. And therefore he is searching.

But in the jungle or in the desert he is not only lost but also a victim of the primitive environment. Like the sage linguistics professor in “The Delicate Prey”: savages cut out his tongue and make of him a dancing clown for their entertainment. Or in the novel, “The Spider’s House,” the 15-year old Amar of Fez wins out over the American writer.

Natural man is superior and defeats the neurotic product of technological society. Someone called Bowles’ modern-man protagonists “fellow-travelers of primitive society”: they search it out, love it, need it, but in the end are defeated by it. For Bowles they are two incompatible cultures. And that is his theme.

“Perhaps this has no significance,” he said and reached for another of the kif cigarettes that seem to keep him going. “I simply want to show how badly prepared the average Westerner is when he comes into contact with cultures he doesn’t know – or only thinks he knows. The more he tries to penetrate it, the worse it gets. Primitive man has retained things that western man has lost and can operate in natural surroundings. Americans are less prepared than Europeans in such circumstances because they think everyone must do it the American way. Therefore it’s hard for them to establish real contact with others. It’s a paradox that self-subsistent primitive man is more adapted for communal life than is dependent western man, whose attempts at communal life are disasters.

“Primitives have a communal life. No one owns anything. Everything belongs to all. This couldn’t work in advanced societies. As soon as personal property appears, you have to invent another system. Before arriving in the desert, Port – in “Under The Sheltering Sky” – said he didn’t need a passport to prove he is a member of mankind. But when he loses his passport traveling around in the desert, he is lost: he loves and needs the primitive world and seeks salvation in it, but he is demolished by the loss of his passport. He says he is only half a man without it, that he no longer knows who he is. Like his wife, who likes to spread her things around the room and look at them; by observing familiar objects she regains her identity.

Dinner at Bowles’: He cooked a dinner of roast chicken and rice in a non-American kitchen, haphazardly, distractedly but with great delicacy, claiming that he cooks only to survive. I believed he liked the preparation and the intimate ceremony more than the actual consumption. Thin, wiry, resilient and underneath tough, he only nibbled at his food.

“I’ve had about every disease,” he claimed, “from typhoid to hepatitis to dysentery but I think I’m healthy. I don’t even want to think about illness for there are no doctors here and little medicine. I’d have to go abroad if I fell ill. If it comes, it comes, I don’t worry about it.” Let it come down was his philosophy.

He was sitting on the floor with his back to the fire while we dined from a low Moroccan table. The room was half dark, the logs crackled and we could hardly hear the rain, for me omnipresent in his literature – which he denied. Instead we talked about the desert, the setting of his first novel, Under The Sheltering Sky.

“I had written poetry about the desert before I visited it the first time. I had a feeling for it. It has always provided me with many materials. The desert for me is exciting, more romantic than the sea, hard to encompass in words. I had always imagined the desert with dunes every place; it isn’t like that at all. Few dunes, mostly wasteland.”

His desert is endless. In the same novel about an American couple in the Sahara, each is seeking – the minor characters too - himself in that primitive world. “They made the fatal error,” Bowles said rather distantly as if it no longer concerned him, “of treating time as non-existent. They imagined that nothing would ever change, that it didn’t matter if you did something this year, or in ten years. Perhaps those who live here a long time begin to think that way.

“But what can we do about time? It goes very fast and I’ll soon be dead. [He was in his late seventies but in fact lived a number of years afterwards.] I regret that our life span is limited but I can do nothing about it. When you get to the end you have to accept it.

“Despite the grim endings in my stories I’m not interested in death except in that it puts an end to life. Everyone shares that fate. I can’t really think about it because for me it is non-existence. I’m only interested in what can be seized by consciousness. Once that’s gone, there’s nothing left. If you think there is life after death then you can fear death. If not, then there is nothing to fear except the act of dying. You can hope for a quick death. That’s the moment when you’re most alone. Of course if one is not certain there is nothing afterwards, it’s another matter. You believe what you want. A matter of volition. I just think about how long it will take.

“I’ve never been tempted by suicide but I have thought about it. My wife Jane – the writer Jane Bowles – was sick for a long time before she died. She begged me to end it all for her. And I would have done it if there were no law against it for I believe in euthanasia.”

Volition is a word Bowles used frequently. However, not didactically. His existentialism, he said, derived from instinct rather than from active intellectual search. Yet he was not anti-religious as such. “Although religious ideas permeate everything, they have played little role in my life. I never had religious instruction as a child since my parents and grandparents were agnostics. I’m not even anti-Christian and I don’t think Christianity is negative; all religions offer something. Christianity interests me in the same way as do Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism or Islam. Islam is no better than Christianity.

“I think each religion is made for certain people. Religions, unlike invented political ideologies, sort of grew along with man. Religions are part of man. But if I say that all religions are interesting, in general I would say it’s better to leave them alone.”

I remember my feelings of nostalgia and a certain sense of incompleteness when I left Bowles’ apartment the last day. Nostalgia for the former times he experienced in his life; incompleteness for the little I had learned about this complex man. Paul Bowles, outwardly exquisitely polite and considerate, was distant from the world. He didn’t need it any longer.

“It’s dark and drizzling walking down from the Marshan,” I ’m reading from a faded draft of my interview with Paul Bowles. “A light fog hangs over the rooftops of the elegant El Minzah Hotel on Rue de la Liberté, one of Bowles’ locales. But he doesn’t go to such places anymore. No more trips to the desert. No more walks through the old cities. His life is now quiet and meditative. The Bowles path leads across the Zocco Grande into the labyrinth of his Tangier medina, to the Café Tingiz, ringed by a maze of passages, the Casbah above, the port below, the setting of “Let It Come Down”. Bowles knows every nook and corner of it. He doesn’t have to visit it anymore. Nor does he visit the great Fez medina, the background of “The Spider’s House.” They somehow belong to him.”

P.S. Like many writers of his generation, Bowles was interested in and wrote for the cinema. In a letter to me in Rome he later reminded me of the time he was holed up in a Rome hotel to write the dialogue for Visconti’s famous film, “Senso.” He wanted to set the record straight for me: “I shared credits on it with Tennessee Williams, whom Visconti called in afterwards to rewrite the love scenes because he found mine too objective and removed. That was all right with me; I left Rome and went to Istanbul.”

A few more words about Paul Bowles and the cinema world: shortly after my interview with Bowles appeared in Rome’s Espresso Magazine – one of the first interviews with the writer published in Italy – I had the privilege of interviewing the film director, Bertolucci [1988] who said he was looking around for ideas for his next film, which he wanted to do in some exotic place. He had Africa in mind. I only mentioned Bowles’ book “Under The Sheltering Sky” and my recent interview with him, so great was my surprise when some time later Bertolucci announced he was going to do a film version of that novel, with Paul Bowles himself as consultant. In the end, Bowles, still active, an unwilling traveler, did travel some with the cast in the Sahara. Unfortunately I can’t say what Bowles really thought of the Bertolucci film entitled “Té nel deserto.” [Tea In The Desert.]

At the time I published the same interview with Paul Bowles on the cultural pages of the Dutch newspaper, NRC Handelsblad, under the title “Stranger In A Strange Land.” Since then books and many articles, like “The Last Existentialist” by the poet Daniel Halpern in the New York Times Book Review, have been published about this still mysterious American writer.

If the totality of Paul Bowles’ literary production is not voluminous, his works taken together nonetheless constitute a consistent statement about life – an accomplishment for any artist.

Gaither Stewart

Rome, Italy

Email: GaitherStewart@libero.it

GAITHER STEWART serves as Senior Editor, European Correspondent for The Greanville Post, and general literary and cultural affairs correspondent. A retired journalist, his latest book is the essay asnthology BABYLON FALLING (Punto Press, 2017). He’s also the author of several other books, including the celebrated Europe Trilogy (The Trojan Spy, Lily Pad Roll and Time of Exile), all of which have also been published by Punto Press. These are thrillers that have been compared to the best of John le Carré, focusing on the work of Western intelligence services, the stealthy strategy of tension, and the gradual encirclement of Russia, a topic of compelling relevance in our time. He makes his home in Rome, with wife Milena. Gaither can be contacted at gaithers@greanvillepost.com. His latest assignment is as Counseling Editor with the Russia Desk. His articles on TGP can be found here.

GAITHER STEWART serves as Senior Editor, European Correspondent for The Greanville Post, and general literary and cultural affairs correspondent. A retired journalist, his latest book is the essay asnthology BABYLON FALLING (Punto Press, 2017). He’s also the author of several other books, including the celebrated Europe Trilogy (The Trojan Spy, Lily Pad Roll and Time of Exile), all of which have also been published by Punto Press. These are thrillers that have been compared to the best of John le Carré, focusing on the work of Western intelligence services, the stealthy strategy of tension, and the gradual encirclement of Russia, a topic of compelling relevance in our time. He makes his home in Rome, with wife Milena. Gaither can be contacted at gaithers@greanvillepost.com. His latest assignment is as Counseling Editor with the Russia Desk. His articles on TGP can be found here.

[premium_newsticker id=”154171″]

Parting shot—a word from the editors

The Best Definition of Donald Trump We Have Found

In his zeal to prove to his antagonists in the War Party that he is as bloodthirsty as their champion, Hillary Clinton, and more manly than Barack Obama, Trump seems to have gone “play-crazy” -- acting like an unpredictable maniac in order to terrorize the Russians into forcing some kind of dramatic concessions from their Syrian allies, or risk Armageddon.However, the “play-crazy” gambit can only work when the leader is, in real life, a disciplined and intelligent actor, who knows precisely what actual boundaries must not be crossed. That ain’t Donald Trump -- a pitifully shallow and ill-disciplined man, emotionally handicapped by obscene privilege and cognitively crippled by white American chauvinism. By pushing Trump into a corner and demanding that he display his most bellicose self, or be ceaselessly mocked as a “puppet” and minion of Russia, a lesser power, the War Party and its media and clandestine services have created a perfect storm of mayhem that may consume us all.— Glen Ford, Editor in Chief, Black Agenda Report

In his zeal to prove to his antagonists in the War Party that he is as bloodthirsty as their champion, Hillary Clinton, and more manly than Barack Obama, Trump seems to have gone “play-crazy” -- acting like an unpredictable maniac in order to terrorize the Russians into forcing some kind of dramatic concessions from their Syrian allies, or risk Armageddon.However, the “play-crazy” gambit can only work when the leader is, in real life, a disciplined and intelligent actor, who knows precisely what actual boundaries must not be crossed. That ain’t Donald Trump -- a pitifully shallow and ill-disciplined man, emotionally handicapped by obscene privilege and cognitively crippled by white American chauvinism. By pushing Trump into a corner and demanding that he display his most bellicose self, or be ceaselessly mocked as a “puppet” and minion of Russia, a lesser power, the War Party and its media and clandestine services have created a perfect storm of mayhem that may consume us all.— Glen Ford, Editor in Chief, Black Agenda Report