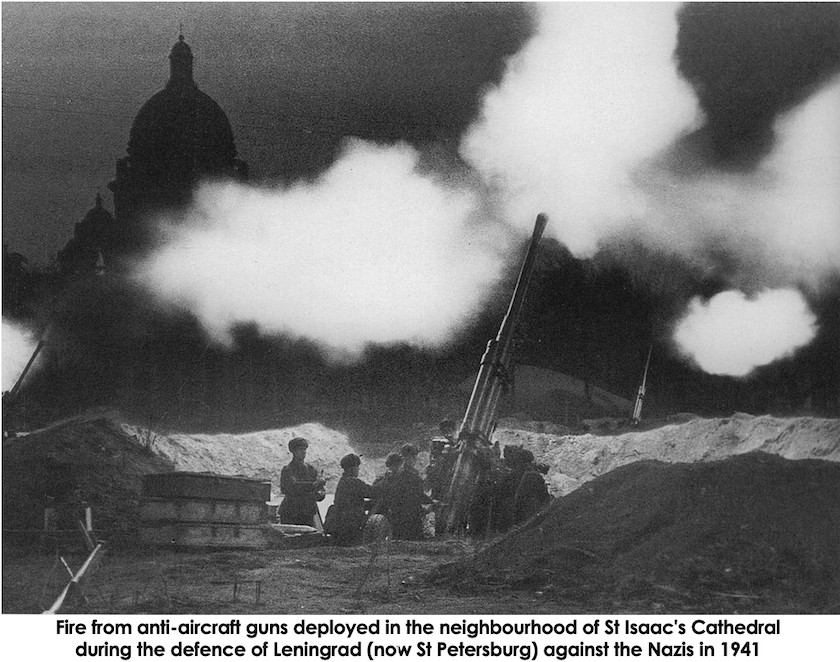

On 16th September, the composer made a special radio broadcast (an excerpt of this broadcast) to encourage the soldiers at the front, saying: “An hour ago I completed the second part of my new work. If I manage to complete the third and fourth parts of this composition, and if it turns out well, I shall be able to call it the Seventh Symphony…. Despite the war-time conditions, despite the danger which is threatening Leningrad, I have written the first two parts in a comparatively short time. Why am I telling you this? I am telling you this so that listeners tuned in now should know that life in our city is normal. Despite the threat of invasion, things are going on as usual in our city. All of us are soldiers today, and those who work in the field of culture and the arts are doing their duty on a par with all the other citizens of Leningrad… Soviet musicians, my dear, numerous comrades-in-arms, my friends! Remember that grave danger faces our art. Let us defend our music, let us work honestly and selflessly… Comrades, I shall soon be completing my Seventh Symphony. My mind is clear and the drive to create urges me on to conclude my composition. And then I shall come on the air again, with my new work and shall nervously await your stern, friendly judgment. I assure you in the name of all Leningraders, in the name of all those working in the field of culture and the arts, that we are invincible and that we are ever at our posts… I assure you that we are invincible.”

That same evening Shostakovich had invited several musicians to his apartment to hear what he had written so far. After he finished the first movement, there was a long silence. An air-raid warning sounded. No one moved. Everyone wanted to hear the piece once more. But the composer briefly excused himself to take his wife Nina and their children Galina and Maxim to the nearest air-raid shelter. When he returned to his guests, he repeated the first movement to the blasts of Luftwaffe bombs and anti-aircraft fire and then proceeded to play the next movement. Their deeply emotional reactions encouraged him to start that night on the Adagio – the third part. He completed this movement on 29th September.

After a month of harrowing conditions in Leningrad, Shostakovich was ordered to evacuate the city. He initially resisted this, but Stalin was determined to protect the most renowned assets of Soviet culture. The composer finally agreed to be evacuated with his family to Moscow and took the first three movements of the symphony along with him. In an article written on 8th October, Shostakovich wrote that his new composition was to be a “symphony about our age, our people, our sacred war, and our victory”.

After a month of harrowing conditions in Leningrad, Shostakovich was ordered to evacuate the city. He initially resisted this, but Stalin was determined to protect the most renowned assets of Soviet culture. The composer finally agreed to be evacuated with his family to Moscow and took the first three movements of the symphony along with him. In an article written on 8th October, Shostakovich wrote that his new composition was to be a “symphony about our age, our people, our sacred war, and our victory”.

With Moscow itself under threat, Russian artists as well as industries were transplanted eastward. Two weeks after their arrival in the capital, Shostakovich and his family boarded a train, along with composers Aram Khachaturian and Dmitri Kabalevsky and members of the Bolshoi Theatre. Their destination was the temporary capital Kuybyshev (today known as Samara on the Volga), over 600 miles east of Moscow. There the family settled into a three-room suite with a grand piano.

Distraught by the devastation he had witnessed in Leningrad and the perils now facing Moscow, Shostakovich felt paralysed and was unable to focus creatively for several weeks. But in early December, when the Red Army succeeded in repelling the Germans before they could reach Moscow, he experienced a renewed burst of energy… and in a matter of two weeks he brought the composition to a triumphant conclusion – on 27th December 1941.

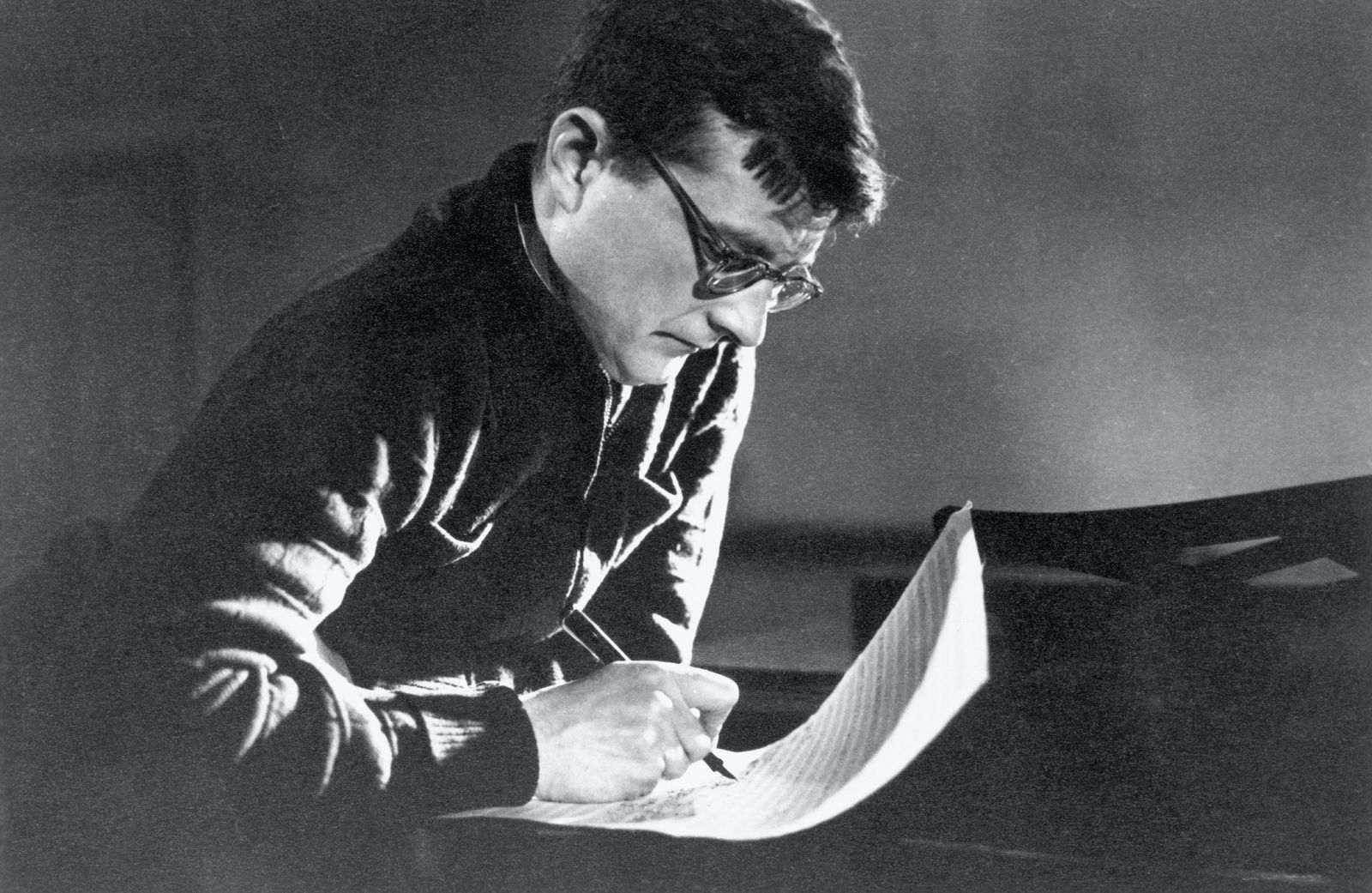

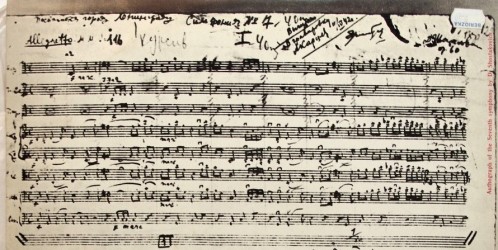

|

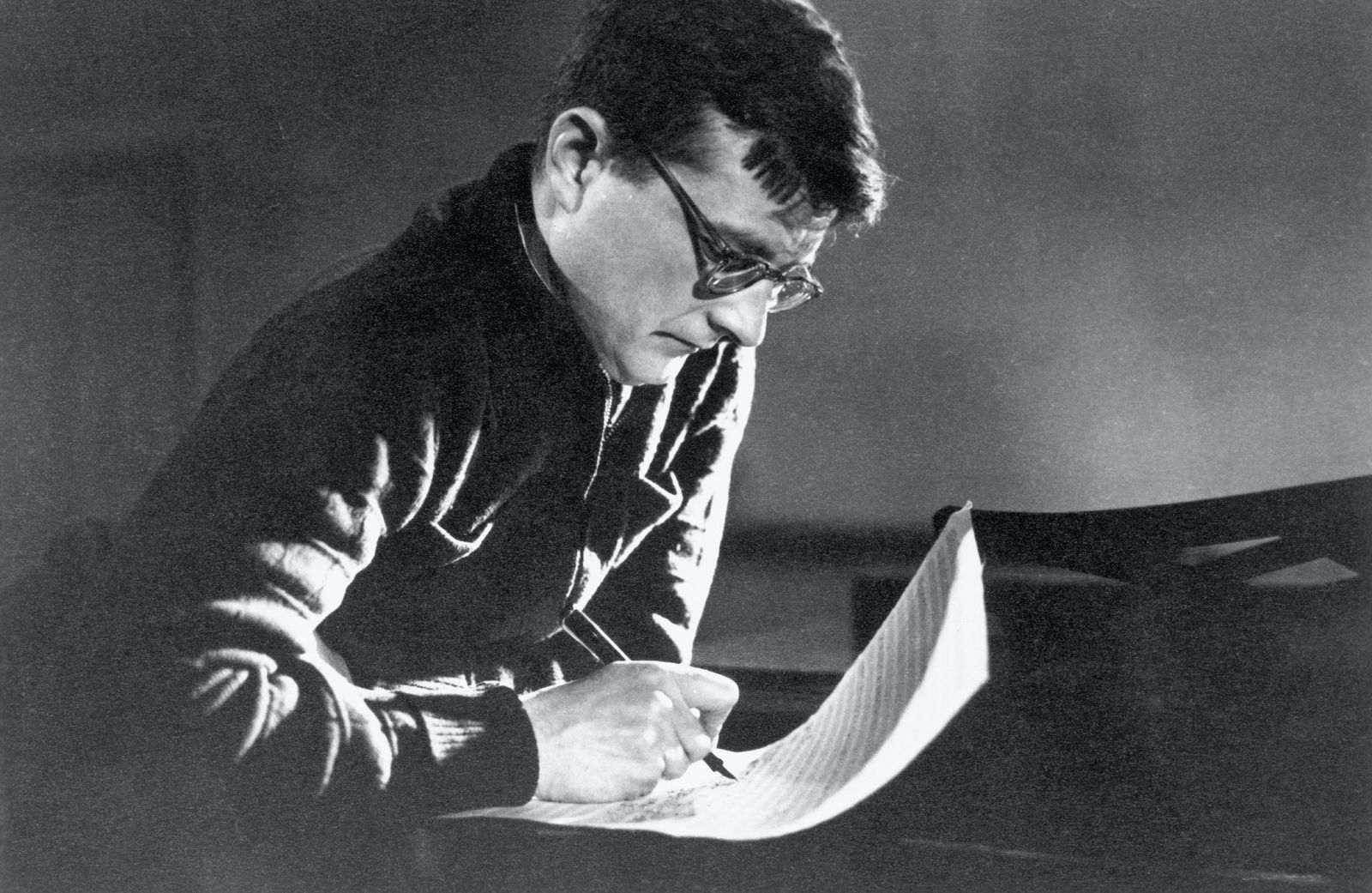

Shostakovich at work. |

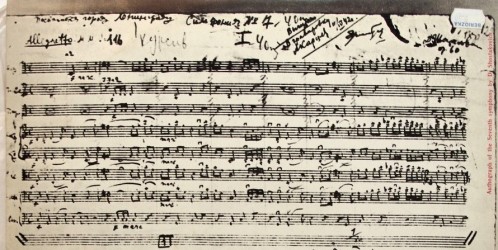

An inscription was written on the title page of the music score, “Dedicated to the City of Leningrad. Dmitry DmitrievichShostakovich” and on the final page, “27.XII.1941. Kuybyshev”.

Conceived on the banks of the Neva and completed on the banks of the Volga, this musical opus became the most legendary musical composition of the entire World War II period… not to mention a social and political achievement on a global scale.

* * *

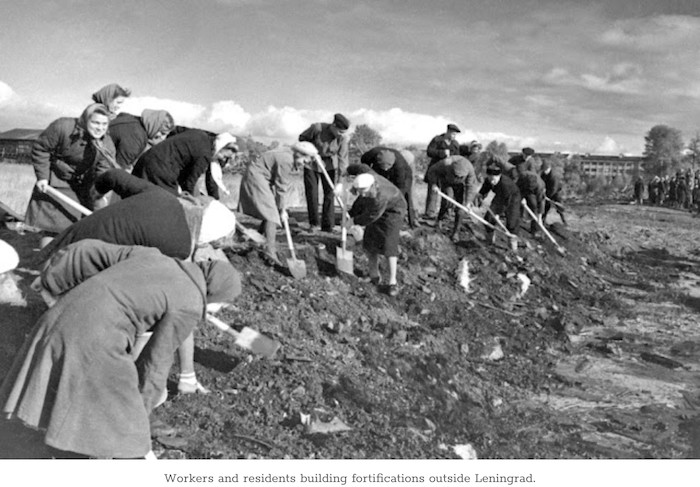

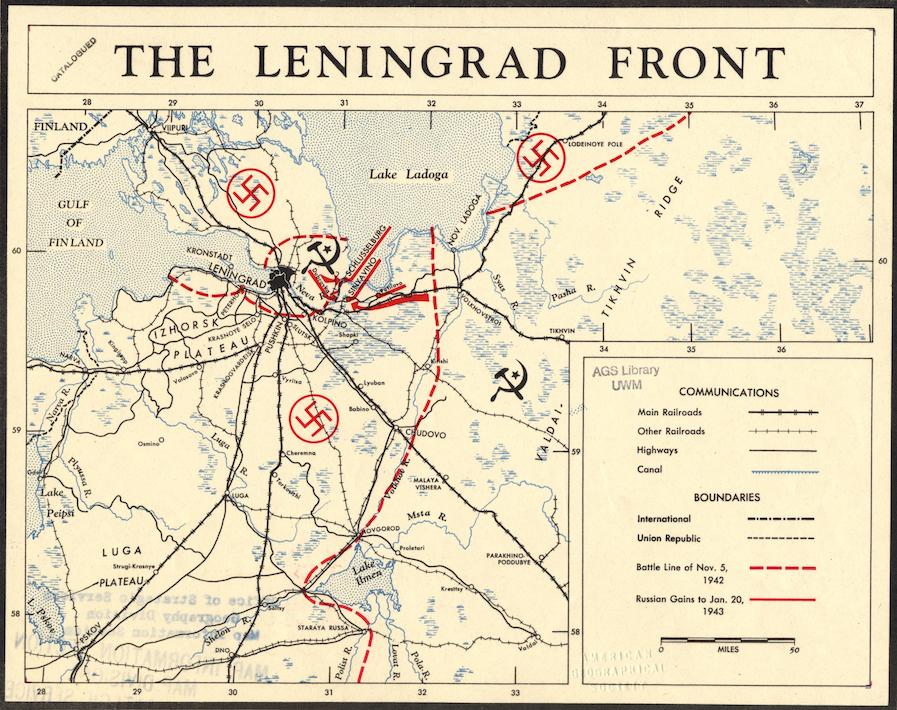

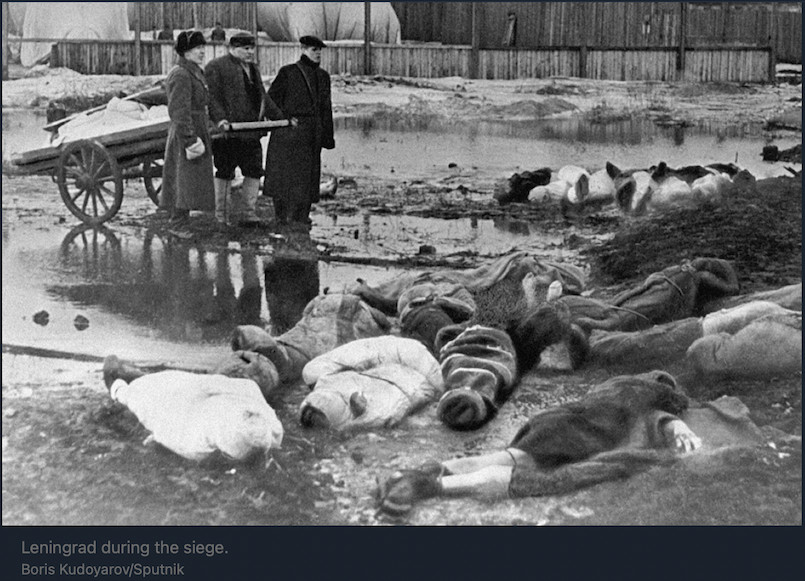

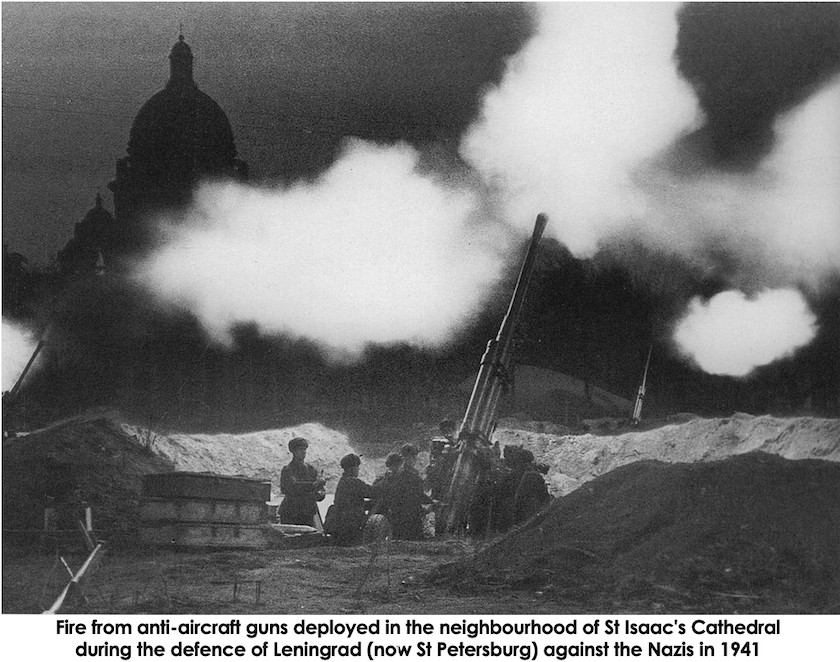

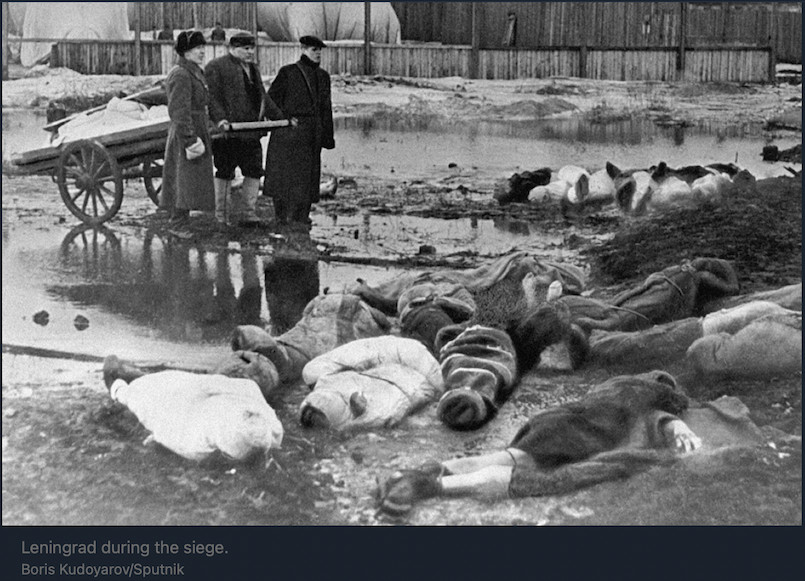

The conditions in Leningrad during the 872 days of the Siege were horrific. Thousands of soldiers died gruesome deaths trying to defend the city, while its inhabitants succumbed to various diseases or famine. The city had become a living hell, with dead bodies littering the streets, since few people could spare the energy to give them a proper burial. In February, special teams removed over 1,000 corpses a day from the streets. Eyewitness reports told of people who had died of cold and starvation lying in doorways in stairwells. “They lay there because people dropped them there, the way new-born infants used to be left. Janitors swept them away in the morning like rubbish. Funerals, graves, coffins were long forgotten. It was a flood of death that could not be managed. Entire families vanished, entire apartments with their collective families. Houses, streets and neighbourhoods vanished.”

On the battlefields, winter temperatures made it impossible to dig pits in the frozen ground, and congealed cadavers were used instead of logs to reinforce trench walls and shelter roofs.

According to official statistics presented at the Nuremberg Trials, as reported by RT, the incessant bombing and shelling of the city killed a total of 17,000 people, while the bitter cold and the famine – as planned by the Germans through the disruption of utilities, water, energy and food supplies – took the lives of another 632,000. Meanwhile, 332,000 soldiers perished. Moreover, many of those who had been evacuated (1,400,000 more – mainly women and children) died during evacuation due to starvation and bombardment.

Historian Michael Walzer summarised that, “More civilians died in the Siege of Leningrad than in the modernist infernos of Hamburg, Dresden, Tokyo, Hiroshima and Nagasaki taken together”. The Siege of Leningrad ranks as the most lethal siege in world history, and some historians speak of the Siege operations in terms of genocide, as a “racially motivated starvation policy” that became an integral part of the unprecedented German war of extermination against populations of the Soviet Union generally.

An article entitled “How Saint Petersburg survived the bloodiest blockade in human history” reported that in October of 2022, the Saint Petersburg City Court finally recognised the Siege as genocide. President Vladimir Putin remarked in November 2022: “Just recently, the blockade of Leningrad was also recognized as an act of genocide. It was high time to do it. By organising the blockade, the Nazis purposefully sought to destroy the Leningraders – everyone from children to the elderly. This is also confirmed, as I have already said, by their own documents.”

The article goes on to describe how President Putin, who was born ten years after the end of the Leningrad Siege, was himself directly affected by the tragedy: “At the beginning of the blockade, the one-and-a-half-year-old son of Vladimir Putin’s mother, Maria Ivanovna, was taken away for evacuation, but he never made it out of the city. According to the official account, the child, Viktor, died of an illness. The only notification his mother received about this was a death certificate. As the Russian leader himself said, she only managed to survive due to the fact that her husband, Putin’s father, had been wounded at the front and received augmented rations, which he passed on to his wife during her daily visits to the hospital. This continued until he fainted from hunger, and the doctors, who understood what was happening, forbade further visits. After leaving the hospital on crutches with a shattered leg, he nursed his wife, who had stopped walking from weakness. Vladimir Spiridonovich had fought on the Neva Bridgehead.” It was on the Neva Bridgehead that he “had had his heel and ankle shattered by a grenade, had to swim across the river and was only able to make it to the right bank with the help of a comrade-in-arms.”

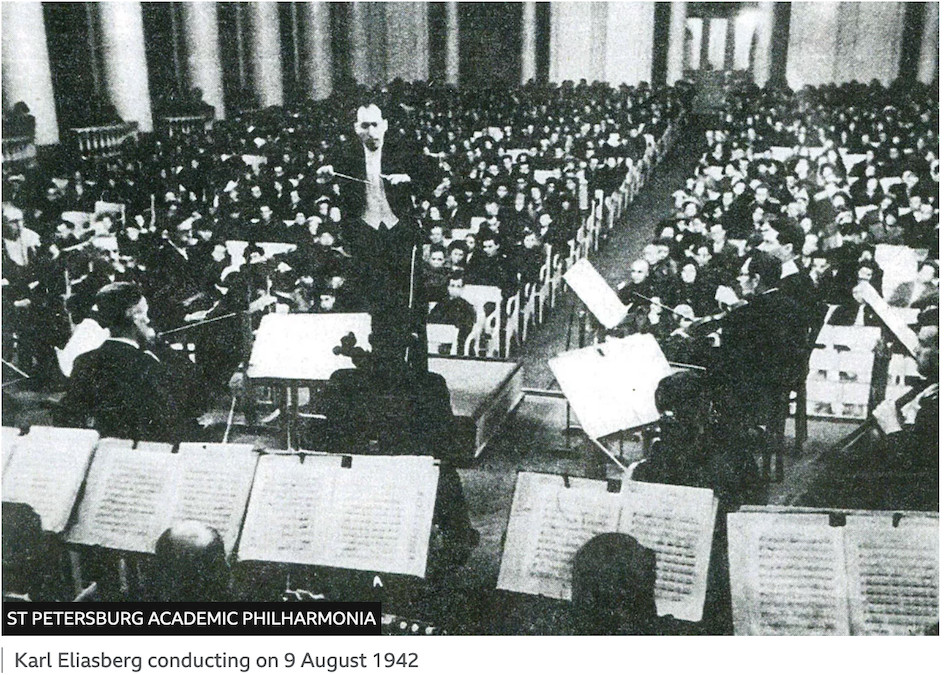

Few important compositions have been performed under such ruthless circumstances as Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 7. At the height of the horrors of the Siege conductor Karl Eliasberg, received orders to begin rehearsals of Dmitri Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony with the Leningrad Radio Orchestra. The city had been under siege for so long that, of the original 40 members of the Leningrad Radio Orchestra, only 15 remained in the city, the rest were dead or fighting on the frontlines. An order had to be issued to soldiers at the battlefront, calling for anyone with musical ability to join the orchestra. In this way, the formation of the symphony united and inspired the people of Leningrad and demonstrated that the people of Leningrad would never give in to their enemies.

Few important compositions have been performed under such ruthless circumstances as Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 7. At the height of the horrors of the Siege conductor Karl Eliasberg, received orders to begin rehearsals of Dmitri Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony with the Leningrad Radio Orchestra. The city had been under siege for so long that, of the original 40 members of the Leningrad Radio Orchestra, only 15 remained in the city, the rest were dead or fighting on the frontlines. An order had to be issued to soldiers at the battlefront, calling for anyone with musical ability to join the orchestra. In this way, the formation of the symphony united and inspired the people of Leningrad and demonstrated that the people of Leningrad would never give in to their enemies.

With winter temperatures below minus 30 degrees Celsius and no electricity or heating during the second winter of the Siege, the orchestra’s pianist Alexander Kamensky kept his hands warm by placing two piping hot bricks on both sides of the piano to radiate some heat. The conductor Karl Eliasberg was so weak he had to be driven to rehearsals on a sledge.

With winter temperatures below minus 30 degrees Celsius and no electricity or heating during the second winter of the Siege, the orchestra’s pianist Alexander Kamensky kept his hands warm by placing two piping hot bricks on both sides of the piano to radiate some heat. The conductor Karl Eliasberg was so weak he had to be driven to rehearsals on a sledge.

Oboist Ksenia Mattus, a survivor, had had to bring her instrument to a craftsman for repair as parts of it had decomposed after the first winter of the Siege. For payment the craftsman had asked her if she could find him a “pussycat” – for his next meal.

Flautist Galina Lelukhina, another survivor, remembers: “On hearing the radio announcement I took my flute under the arm and went. I entered and saw Karl Ilyich Eliasberg, looking dystrophic. He told me: ‘Do not go to the factory anymore. Now you will work in the orchestra’. We were few at first. Some people were brought in the sledge, others walked with a stick.”

The first rehearsal, on 30th March 1942, lasted twenty minutes as everyone was too feeble and exhausted to continue. Ksenia Mattus the oboist compared the conductor’s hand to “a wounded bird falling out of the sky“.

Members of the orchestra not only had to struggle for food each day, they also had to deal with the agonising deaths of loved ones.

As most of the surviving musicians were suffering from starvation, rehearsing was arduous: many collapsed frequently during rehearsals, and three even died in that period. Ultimately, the orchestra was able to rehearse the symphony all the way through only once before the concert.

As most of the surviving musicians were suffering from starvation, rehearsing was arduous: many collapsed frequently during rehearsals, and three even died in that period. Ultimately, the orchestra was able to rehearse the symphony all the way through only once before the concert.

Finally the big day arrived, and the half-starved musicians and their stalwart conductor Eliasberg gathered in Leningrad’s Grand Philharmonia Hall on 9th August 1942 for the grand premiere.

Comrades! We are still here!

The performance of Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony was symbolic in many ways. Hitler had planned a banquet in the Astoria Hotel on the 9th August 1942, the very day of the Leningrad premiere. But not only hadn’t the Germans been able to enter the city, no German air raids interrupted the performance and not a single bomb fell on the Grand Philharmonia Hall on that night although the building was illuminated.

“There were no curtains, and the light from inside the hall was pouring out of the windows into the night,”Trombonist Viktor Orlovsky recalled. “People in the audience were screwing up their eyes as they were no longer used to electric lights. Everyone was dressed in their finest clothes and some even had their hair done. The atmosphere was so festive and optimistic it felt like a victory.”

The performance was broadcast from loudspeakers around the perimeter of the city – both to hearten the Russian people and to convey to the Germans that surrender was out of the question.

For the concert empty chairs were placed in the orchestra to represent those musicians who had died before the performance could be given.

“The halls were always packed – at every performance, which I thought was extraordinary,” Trombonist Viktor Orlovsky went on to recall. “During the hardest period of the Siege, when people’s daily ration dropped to 125 grams of bread, some would exchange their daily meal for a ticket to our concert.” Many Leningraders who didn’t have a radio at home would gather on the streets to listen to orchestral music coming from the loudspeakers. It was an affirmation, an opportunity to rise above one’s physical weakness, fear and starvation.

The 9th of August, 1942, was “a day of the victory at the time of war,” as was described by celebrated Leningrad poet Olga Berggolts, one of the blockade survivors.

Olga Prut, director of “The Muses Weren’t Silent”, a St. Petersburg museum exhibition focusing on the arts during the Siege, said the phenomenon of that colossal dedication to the arts during the blockade was much more than a simple distraction from fears, hunger and solitude. “No one listens to music with such depth as those close to death… Music performs a miraculous transformation on a concentration camp prisoner or the hopelessly ill, turning the slave into a free man. It is an emotional rebirth.”

Many years after the end of the war the conductor Eliasberg was approached by a group of German tourists, who had been on the other side of the barricades and who had listened to his orchestra performing Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony. They had come specifically to tell the conductor that back then on 9th August 1942 they realised they would never take Leningrad. Because, they said, there was a factor more important than starvation, fear and death. It was the will to stay human.

Tatiana Vasilyeva, a survivor of the Siege and a spectator of that legendary performance, was to later reminisce: “When I entered the hall, tears filled my eyes, because there were so many people, all in a state of elation. We listened with such emotion, because we had all lived for this moment – to come to the Philharmonia Hall, to hear this symphony. This was a living symphony – it’s the one we lived. This was our symphony. The Leningradskaia…”

* * *

This struggle continues to this day.

* * * * *

“Shostakovich 7th Symphony”

Brotherhood.

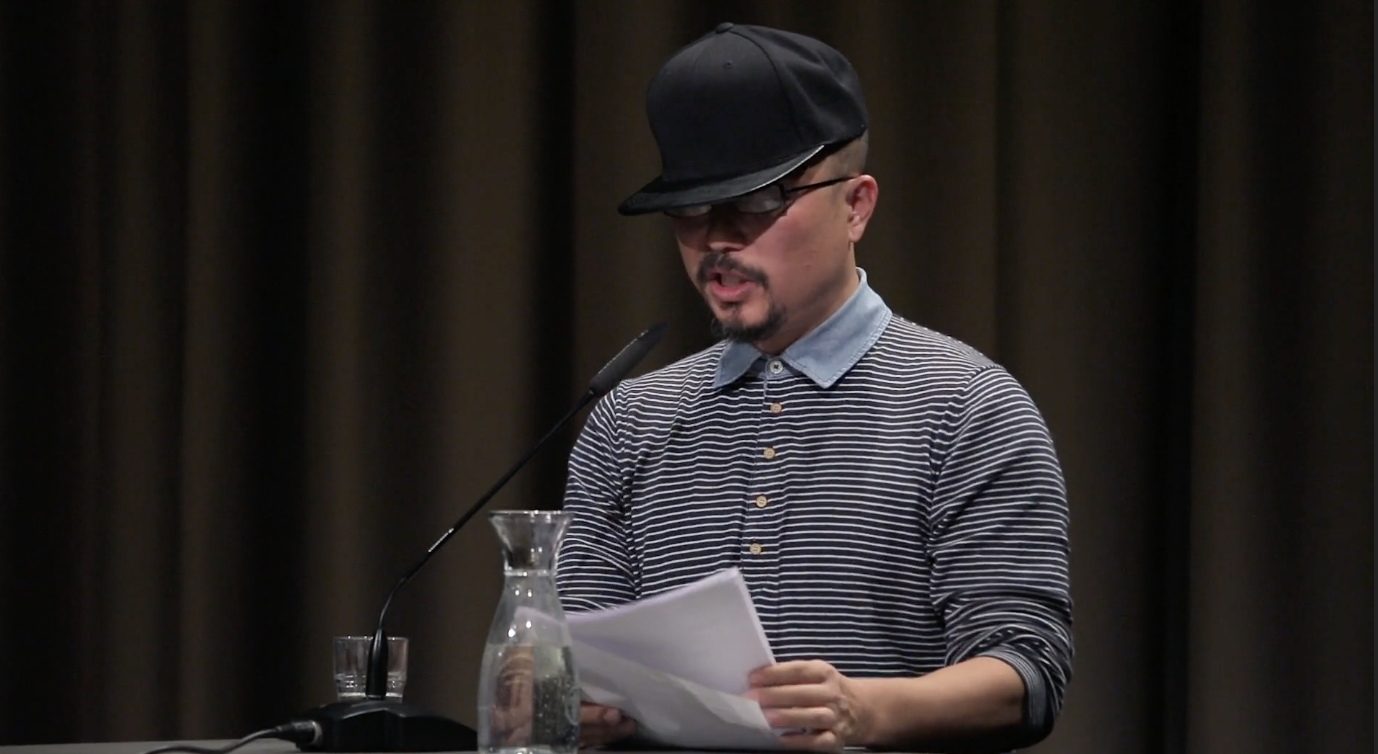

Pepe Escobar is an independent geopolitical analyst. He writes for RT, Sputnik and TomDispatch, and is a frequent contributor to websites and radio and TV shows ranging from the US to East Asia. He is the former roving correspondent for Asia Times Online. Born in Brazil, he's been a foreign correspondent since 1985, and has lived in London, Paris, Milan, Los Angeles, Washington, Bangkok and Hong Kong. Even before 9/11 he specialized in covering the arc from the Middle East to Central and East Asia, with an emphasis on Big Power geopolitics and energy wars. He is the author of "Globalistan" (2007), "Red Zone Blues" (2007), "Obama does Globalistan" (2009) and "Empire of Chaos" (2014), all published by Nimble Books. His latest book is "2030", also by Nimble Books, out in December 2015.

Pepe Escobar is an independent geopolitical analyst. He writes for RT, Sputnik and TomDispatch, and is a frequent contributor to websites and radio and TV shows ranging from the US to East Asia. He is the former roving correspondent for Asia Times Online. Born in Brazil, he's been a foreign correspondent since 1985, and has lived in London, Paris, Milan, Los Angeles, Washington, Bangkok and Hong Kong. Even before 9/11 he specialized in covering the arc from the Middle East to Central and East Asia, with an emphasis on Big Power geopolitics and energy wars. He is the author of "Globalistan" (2007), "Red Zone Blues" (2007), "Obama does Globalistan" (2009) and "Empire of Chaos" (2014), all published by Nimble Books. His latest book is "2030", also by Nimble Books, out in December 2015.![]() Don’t forget to sign up for our FREE bulletin. Get The Greanville Post in your mailbox every few days.

Don’t forget to sign up for our FREE bulletin. Get The Greanville Post in your mailbox every few days.