The rule of modern Capitalism is rooted in lies. It rules, legitimates itself and thrives on lies. Truth kills it.

MINDFUL ECONOMICS

By Joel C. Magnuson /366 pp, Pilot Light, 2007

(Originally published Jul. 8, 2011)/ Revised Nov. 15, 2014

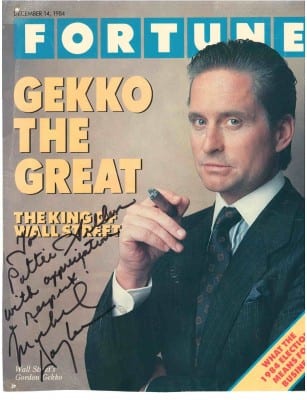

"The richest one percent of this country owns half our country's wealth, five trillion dollars. One third of that comes from hard work, two thirds comes from inheritance, interest on interest accumulating to widows and idiot sons and what I do, stock and real estate speculation. It's bullshit. You got ninety percent of the American public out there with little or no net worth. I create nothing. I own."—Gordon Gekko to Bud Fox (Wall Street, 1987, directed by Oliver Stone)

Given the confusion that underscores so much of the discussion about "economics" in the United States, especially these days when both parties loudly debate with a straight face the "necessity" of curbing "entitlements" (social security, Medicaid, Medicare, public pensions, etc.) to balance the budget, we thought republishing this article might be of some utility to those engaged in exposing these lies for what they are. I have taken the opportunity of this book review on alternative economics to explore some of the systemic distortions supporting the almost universal acceptance of neoclassical economics as a faithful and unbiased descriptor of reality, which it certainly is not. —PG

THIS IS AN IMPORTANT BOOK about a subject—economics—often totally misreported by economically illiterate and biased media. Yet, understanding the reality of economics—or rather, a nation's political economy— is critical to any person wishing to make sense of the world, and essential to choosing rationally on the political map.

It's obvious that if people really understood what's going on in society, and their place in it, especially the larger issues that define what a healthy and truly democratic society is all about, they would be far less likely to vote against their own interest, swear allegiance to myths, criminals and scoundrels in the political class, or act in a selfish manner injurious to the majority of their fellows. Yet that is exactly what we observe among broad segments of the population of many nations, the most notable case being the US, where "irrational" voting patterns have become so scandalously common and fiercely defended as to make the American electorate something of an enigma if not a laughingstock to many observers around the globe. So how do we explain this? The short answer is conditioned behavior injected from above, or "false consciousness." America is a nation overwhelmingly ruled by carefully abetted ignorance and massive propaganda, both of which bolster the plutocratic status quo.

Manipulation an old story

The rise of lies and eventually modern propaganda as a tool of governance was largely inevitable, hardwired almost in the evolution of our species through the highly imperfect stages of its grand journey (which still continues), from primitive communism to scientific, deliberate communitarianism.

The rise of lies and eventually modern propaganda as a tool of governance was largely inevitable, hardwired almost in the evolution of our species through the highly imperfect stages of its grand journey (which still continues), from primitive communism to scientific, deliberate communitarianism.

Since the rise of class-divided society thousands of years ago, chiefly as a result of agriculture, animal domestication, sedentarism, etc., all of which permitted a food surplus, the puny privileged minorities at the top have relied on some type of false consciousness (backed up by liberal applications of violence when circumstances dictated it) to keep the disorganized majorities pliant, divided, and in check.

Religion and the monopoly of violence by the upper classes and their henchmen—and later the modern nation state—have served this purpose admirably for many centuries, but with the emergence of the newfangled democratic ideas in the wake of the French revolution (and associated notions of egalitarianism, secularism, and broad enfranchisement introduced by the ascendant European middle class —the bourgeois—in their effort to attract as many supporters as they could against the decrepit feudal order), more refined and updated methods of social control became necessary.

The rapid strides made by science and technology over the last 200 years have helped immensely in this regard, by facilitating the creation of mass communications media. It's noteworthy that modern propaganda, currently embedded in myriad platforms, from radio and television to mass circulation newspapers, the Internet, etc., did not retire its ancient counterparts such as the religious pulpit, or the royal pomp and circumstance designed to impress the masses; nor has it completely done away with the necessity of state violence against resolute dissidents. It has simply added another monumental weapon to the arsenal of the ruling classes—in today's world, mostly the corporate bourgeoisie—to shape the fate of nations according to their whim.

Prevailing ideology mirrors the ruling class interests

For Marx, ideologies appear to explain and justify the current distribution of wealth and power in a society. In societies with unequal allocations of wealth and power, ideologies present these inequalities as acceptable, virtuous, inevitable, and so forth. Ideologies thus tend to lead people to accept the status quo. The subordinate people come to believe in their subordination: the peasants to accept the rule of the aristocracy, the factory workers to accept the rule of the owners, consumers the rule of corporations. This belief in one's own subordination, which comes about through ideology, is, for Marx, false consciousness.

That is, conditions of inequality create ideologies which confuse people about their true aspirations, loyalties, and purposes.[2] Thus, for example, the working class [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Political_consciousness] has often been, for Marx, beguiled by nationalism, organized religion, and other distractions. These ideological devices help to keep people from realizing that it is they who produce wealth, they who deserve the fruits of the land, all who can prosper: instead of literally thinking for themselves, they think the thoughts given to them by the ruling class. [See Political Consciousness]

To Marx's critics this sounds like a totalitarian explanation, a product of vulgar theorizing. Obviously false political consciousness does NOT explain every single contemptible, cruel, or stupid act carried out by human beings, individually or collectively; such behavior long preceded and probably will long persist after the elimination of "class society", but it goes a long way to explain the curious and persistent disarray found across the board in most class- divided nations today (Disraeli himself called Britain a kingdom split into two irreconcilable nations, "the nation of the rich and the nation of the poor..."). What's more, via the expansion and corruption of mass media, the level of social confusion has tangibly grown. For since at least the late 19th century, shadowing the emergence of "the masses" as an important player in history, and their claim to ultimate sovereignty, there's been an enormous expansion of the tools and wiles of propaganda for the purpose of political manipulation, a fact facilitated by the concurrent growth of corporate-dominated media. As Chomsky, among others, reminds us,

Controlling the general population has always been a dominant concern of power and privilege, particularly since the first modern democratic revolution in 17th century England. The self-described "men of best quality" were appalled as a "giddy multitude of beasts in men's shapes" rejected the basic framework of the civil conflict raging in England between king and parliament. They rejected rule by king or parliament and called for government "by countrymen like ourselves, that know our wants," not by "knights and gentlemen that make us laws, that are chosen for fear and do but oppress us, and do not know the people's sores." The men of best quality recognized that if the people are so "depraved and corrupt" as to "confer places of power and trust upon wicked and undeserving men, they forfeit their power in this behalf unto those that are good, though but a few." Almost three centuries later, Wilsonian idealism -- as it is standardly termed -- adopted a rather similar stance. Abroad, it is Washington 's responsibility to ensure that government is in the hands of "the good, though but a few." At home, it is necessary to safeguard a system of elite decision-making and public ratification ("polyarchy" in the terminology of political science).

Concluding that,

Wilson 's own view was that an elite of gentlemen with "elevated ideals" must be empowered to preserve "stability and righteousness"; "stability" is a code word for subordination to existing power systems, and righteousness will be determined by the rulers. Leading public intellectuals agreed. "The public must be put in its place," Walter Lippmann declared in his progressive essays on democracy. That goal could be achieved in part through "the manufacture of consent," "a self-conscious art and regular organ of popular government." This "revolution [in the] practice of democracy" should enable a "specialized class [of] responsible men" to manage the "common interests [that] very largely elude public opinion entirely." (See, N. Chomsky, Priorities & Prospects)

Thus, the object of most propaganda since its inception in the papal chambers of the 17th century—whether commercial or political—has remained the same, to generate and buttress false consciousness for the almost exclusive benefit of the propagandizing agents—in the vast majority of cases— members of the upper classes. Today, the arsenal of modern ideological propaganda comprises many weapons, and practically no field of social communication is exempt from its reach. Thus, not only are the news media and politics, per se, terminally infected with propaganda in favor of the status quo, as we might expect, but so are all forms of ostensibly non-ideological activity, such as mainstream television entertainment, and even other precincts such as academia whose very mandate is to explore reality without ideological blinders. Indeed, it's precisely the fact that in our modern world the social sciences—economics, sociology, political science, and even the humanities—have been utterly corrupted, turned into shameless vectors for capitalist propaganda, that justifies the discussion of false consciousness in a review of a book like Joel Magnuson's Mindful Economics, which challenges prevailing economic orthodoxy. For mainstream economics in its present (bourgeois) form is a huge fount of pseudo information about the real world, and its cascading, rarely questioned toxic effects can be found in practically all corners of society where the public goes for answers.

As argued earlier, false political consciousness has always worked to prop up the status quo. In the 14th century, for example, embedded in fanatical religiosity and ignorance, it justified feudal absolutism. In our time, it props up capitalism and its ultra violent offshoot on the global stage, imperialism. As such, it presents true democrats (small "d") with a tough challenge: Systemic propaganda, the constant dissemination of false consciousness is not just an irritant. Because it delays the development of forces capable of dealing effectively with the reform, delegitimization, and finally elimination of capitalism, it's showing itself to be lethal now not only to the survival of democracy but to all planetary life as we know it. All capitalist regimes—when not vigorously opposed—eventually degenerate into profoundly undemocratic arrangements.

Adam Smith: Often invoked, rarely read.

From the ruling orders' perspective, the wages of propaganda have been substantial. In the countries that pretend to operate as democracies, false consciousness among the masses allows the upper classes to run society in their own narrow self-interest while pretending to do so in the interest of all, as true democracy would require. Enormous, mind-boggling wealth and power are thus rapidly accumulated by the tip of the social pyramid in all societies riddled with inequality. In America, an empire on the move for at least a century now, and one of the most income-polarized nations in the developed world, the ideological stranglehold has allowed the US ruling class not only to make a mess of domestic policy, but the freedom to engage with relative impunity in constant and murderous meddling in the affairs of scores of other nations, as the case of Iran, Korea and Vietnam a generation ago, and Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya and Syria today, so eloquently confirm. And while at the "micro level" commercial propaganda (i.e., advertising) may induce us only to switch from one brand of detergent to another, a fairly innocuous act, at the "macro level" of class propaganda the effects are far more ominous, since the latter seeks to influence not only the direction but the very nature of the society we inhabit.

"We make the rules, pal. The news, war, peace, famine, upheaval, the price of a paper clip. We pick that rabbit out of a hat while everybody sits around wondering how the hell we did it. Now you’re not naïve enough to think that we’re living in a democracy, are you, Buddy? It’s the free market, and you’re part of it."—Gordon Gekko, Wall Street (directed by Oliver Stone)

As might be expected the instruments to mould opinion in a significant manner are jealously guarded by the ruling classes everywhere. In capitalist America, these tools are literally priced out of the reach of most common mortals. This is logical and consistent with the wealth and power distribution of such societies, where the savvier sectors of the plutocracy understand that the monopoly of opinion manipulation is vital to the survival of their system. Outright repression can certainly ensure a level of compliance, sometimes for a generation or two, but in the long run intimidation cannot guarantee political stability or legitimacy. Only covert mind control can deliver that. Thus by far the most efficient solution is when we are made to carry the chains and prisons right inside our heads. Policing our own actions while still believing in our total freedom is simply a diabolically effective formula to ensure perpetual bondage, but to make it fly the system requires the confluence of many critical factors, including the complicity of academia.

The role of academia

Academia is both a fountainhead and a battlefield for ideology, sometimes as a radical questioner and denouncer of the status quo, as befits its mission to look for truth without "fear or favor", and other times as an obsequious servant of the establishment, a powerful validator of accepted class-buttresing orthodoxy. Besides having some natural audiences in their own students, and given the unquestionable authoritativeness of their voices, academics and leading public intellectuals are in an exquisite position to hold forth on any subject they care to illuminate (or obscure) —pushing for conformity or rebellion according to personal character. Therein lies their power and the problem they present to the status quo—when they choose to oppose it. That their opinions count a great deal can be gleaned from the annals of history, from Galileo to our day, and reminders occur with notable frequency. (For a variety of reasons, including the inroads of career-induced conformity and the suffocating power of hypermedia, the influence of dissenting academia has diminished considerably in the last 30 years.)

Back in 1973, one of the first things that CIA-sponsored Chilean dictator Gen. Augusto Pinochet did was to "intervene" the nation's universities (at least those deemed by the regime to be festering grounds for subversivos and democratic action), and appoint army generals to serve as rectors and deans of a number of distinguished colleges. In the wake of such move, which lasted well into 1976, all the social science faculties and humanities—sociology, economics, history, philosophy, and the main school of journalism—were simply shut down, their staff jailed, exiled, or persecuted, in some cases simply "disappeared". With the unceremonious disbanding of the schools, the students were sent home, or, more precisely into limbo.

Our man in Chile: Augusto Pinochet, Milton Friedman's most notorious disciple.

Concurrent with these "politically hygienic" measures (as one of the regime's spokespeople so crisply called it), Pinochet brought in and soon imposed at bayonet point a "shock treatment model" for the Chilean economy, the free-market fundamentalist prescription preached by University of Chicago professor Milton Friedman and his acolytes, the infamous "Chicago Boys" directly tutored by one of Friedman's colleagues, Arnold Harberger. As many radical and even centrist economists around the world had repeatedly warned, the pain of the "shock" was mainly absorbed by the poorest sectors, who lost a significant portion of their hard-won income, practically all government subsidies (however meager, still significant in their case), and all rights and instruments of self-defense against the depredations of management, as labor unions were banned and their leaders simply jailed or murdered. While the bourgeois media—led by the American press—wasted no time in writing and singing panegyrics to the new "Chilean miracle," thereby helping to whitewash the dictator's numerous crimes, the reality on the ground was far different, and Chile's economic wounds have never healed.

Friedrich Von Hayek: Friedman's intellectual mentor.

Pinochet's move against the social sciences may have been characteristically brutal but it had logic behind it. As suggested earlier, the mainstream social sciences—especially sociology and economics—are critical for the ongoing legitimation of "bourgeois democracy"—itself something of an oxymoron (it's always far more bourgeois than democratic). With their main theorems presented as truths comparable in impartiality (and most importantly, inevitability) to the laws of nature, their postulates sell the public a vision of society calculated to bolster acceptance of a deeply undemocratic status quo favoring capitalist values and policies. In this way, they act as legitimators and apologists for the system, and not as free and independent inquirers of truth. So much for the basic approach they propound (about which more later), but this abdication of their duty to society is often magnified by the fact that, when they do engage in research, their tools and priorities are reserved for the advancement and discovery of notions of benefit to their masters—the business class in power—and perforce inimical or of only tangential benefit to the masses. Similar deformations of focus and priority are seen in all social institutions dominated by the capitalist class, especially the media, the ubiquitous harlot, whose programming choices and content reflect identical biases. [Has anyone noticed the proliferation of business and "financial" news programs on the commercial and even PBS side of television, all fixated on breathless, often boosterish, analyses of the perennial, largely incomprehensible Wall Street roller-coaster, a casino by any standard, and endless discussions of markets, bonds, stocks, and what not, in a nation where no more than 5% of the people actually have a net worth above $100,000 or real portfolios of any kind? If that is not rank capitalist cheerleading, what the heck is that all about?]

What's wrong with "neoclassical" economics?

he average person, including well-educated people, can't begin to answer that question properly. For one thing, they simply don't have a clue. Mainstream departments of economics do not teach anything but orthodox views of the "dismal science" (so nicknamed in 1849 by conservative economist Thomas Carlyle on account of Malthus' grim predictions, and because the discipline dealt with scarcity, subsistence and "other dreary subjects"). Now, orthodox doesn't necessarily mean wrong. "Orthodox" astrophysics, biology, math, or chemistry, even medicine (which is partly an art), for example, are pretty much on the mark. Their theories align as much as human beings can ascertain with observable phenomena, which, incidentally, are far easier to study in these branches of science than in society, since the latter, being immensely complex and in perennial flux, can't be turned into a satisfactory lab model. But the chief obstacle is political. Natural and pure scientists have the luxury of pursuing facts with a far more independent mind than their cousins in economics, anthropology or sociology, for example, chiefly because their findings and positions do not affect the fortunes of powerful sectors of society with a vested interest in a certain version of reality. (The recent arguments about climate change have shown that even natural scientists can get embroiled in class war questions.)

Consider the question of capitalism's "true makeup" for a moment, and how immensely rich and powerful individuals and groups, people who influence or control the destiny and careers of countless academics, journalists, politicians, and similar voices, and who have prospered or lived pretty well under capitalism, would react to the following propositions. How do you think they would choose?

• If capitalism flows from human nature, then replacement is futile, dangerous and foolhardy.

• If capitalism and market freedom are guarantors of democracy, then replacing it is tempting tyranny.

• We have reached the end of history —of ideology (read = the end of the class struggle) because after capitalism we can only look forward to more and better capitalism.

The Nation ("Economic Freedom's Awful Toll"), denouncing in eloquent terms the horrific social costs of the Friedmanian model.

Now, this is not to imply that Samuelson, Friedman, and their numerous progeny, were or are all sellouts and worthless cranks promoted only on the basis of their usefulness to the system, lacking entirely in moral integrity. It would be unfair and inaccurate to deny that there are some brains in that crowd. But even genius is fallible. It's possible to be a true believer in your own theories, be fanatically wrong, so to speak, and still receive accolades from the system boosters because, well, you are useful to them. If nothing else, the system does take care of its own. Under most circumstances orthodoxy pays, and those who do the system's bidding—wittingly or unwittingly—usually gain handsomely.

The need for rectification

All the more reason, therefore, to celebrate the appearance of brave books disputing and exposing this thick tegument of lies, omissions and willful distortions we have come to call "neoclassical economics." Mindful Economics [ME], by a young academic, Joel Magnuson, does that, and it does the job brilliantly and comprehensively. Not since the 1970s, when we saw the last crop of "Goliath slayers" in Hunt and Sherman's Economics—an introduction to traditional and radical views, and, of course, Marc Linder's Anti-Samuelson, had we seen an introductory text to economics so well organized, comprehensive, accessible, and conscientious in its unorthodox analysis of the subject as to merit an unqualified hurrah. For my money, Magnuson's volume easily outweighs the [still] more popular The Divine Right of Capital, by the estimable Marjorie Kelly, if for no other reason that Kelly, like many liberals, seeks to both condemn and exonerate capitalism at once, in her case by producing this fictive criminal beast she calls "corporate capitalism," which apparently (in the tradition of libertarians who continue to be enamoured of the idyllic days of small business) has no historical or evolutionary linkages with standard capitalism! Where does Kelly and her like-minded tribe think "corporate capitalism" sprang from? A new type of phlogiston? Kelly also prefers to talk coyly about 'wealth discrimination"—which I regard as superfluous— instead of class-induced differentials, since class, in the Marxian sense, remains unsurpassed as an instrument to interpret history and society. In that manner, Kelly supposedly seeks to have her cake and eat it too, forgetting that the masses—should they adopt her analysis— would suffer from her deficient diagnosis and inability to sever all ties with a system that has proved its incurable toxicity many times over. Magnuson, I'm happy to report, does not fall for that kind of temporizing.

Friedrich Engels: A superb scholar in his own right, he directed Marx toward the study of economics, and produced some of the earliest classics in the literature of political sociology, basing his writing on firsthand experience of the conditions of life of the English working class which he witnessed in Manchester.

It is said that Engels was once asked by an American reporter how he'd go about fixing or "transcending" capitalism, should he ever have the opportunity to attempt such a feat. The story may be apocryphal, but I can't resist telling it because it is so apt. The journalist was expecting a detailed roadmap to socialist Eden, from indubitably one of the great social visionaries of all time. He was surprised to hear Engels merely say, after a brief moment of reflection, "Upend it." In general, the "distilled wisdom" of the system is poison to the masses, so start by reversing it. If it says "do this", do the opposite. You'll be on safe grounds. Joel Magnuson's book seems to follow the same advice. While presenting all the essential topics that students and the public at large might expect from an overview of standard economics, he "upends" the mainstream approach, while adding to it, and thereby turns a misleading, unnecessarily abstruse, and largely sterile brew into an enlightening journey of new appreciation for the untapped potential of humankind. In that sense, ME is a demystifying tool, a mind detoxifier that also makes economics fun to read. And Mindful Economics helps the reader vaccinate the mind against the blandishments of false consciousness, showing that, in economics, at least, the unorthodox view is far closer to the truth.

Disentangling our minds from the official maze

he history of ideas shows that many notions, when young, carry the spirit of robust free inquiry and a fair dose of altruism, and that as they age, and become accepted and vested in institutions and a tangle of power relations, lose both the freshness and independence of their original approach and often their very reason for being.

The case of economics is perhaps an excellent, some would say, "textbook," example of that trajectory. Economics began as an imperfect science, "political economy," albeit an honest science that recognized in its youth that "economics" doesn't operate in a vacuum (as in today's conceited "science" that long ago dropped the inconvenient "political" from its name) but is always ensconced in a web of uneven power relations that determine the outcome of most transactions.

The "terms of trade" are always uneven, frequently terribly lopsided. A man without a bank account and a family to feed will take just about any job; not so the wealthier party offering the job, who operates under no such compulsion. The latter has a clear upper hand to negotiate a deal and s/he does. This disparity in power also vitiates relations between nations. The developed world has much more clout at the negotiating table—economic, political, and military— than poorer nations, and it shows in a web of dependency that has rendered many of these nations over time less sovereign in the making of internal policy than their status as formally free nations would suggest.

Marx: The formidable curmudgeon. Often attacked, rarely read, seldom understood.

In its infancy—when economics was seen as "political economy"— it recognized such realities. It was, after all, the brainchild of moral philosophers and thinkers such as Adam Smith (far more often spuriously quoted than read), David Ricardo, T. Malthus, J.B. Say, Karl Marx, and others, who sought to discover laws of social organization that might grant humanity—at last—relief from misery, wars, endemic poverty and constant social friction. This period lasted about a full century, and then economics began to take a different coloration. As it matured it took the raiments of a self-conscious ideology for the young capitalist system, which was also receiving a fair boost from Calvinism. Eventually, it went from relevant ideology to apologetics, and from there, in accelerating degeneracy over the last fifty years, to something akin to theology.

Orthodox economics is today so tautological as to be much closer to dogma than science. Lost in next to incomprehensible mathematical models, it seeks to deny its irrelevancy to the average citizen and scandalous subservience to the ruling orders by hiding behind ever more arcane and microscopic applications of its art in friendly venues: corporate corridors, academic towers, or other rarified precincts of the financial-capital sector that dominates the system. It is here that the misplaced focus of contemporary economics is revealed in all its squalid nakedness. For the individuals directly benefiting from such "knowledge" are relatively few, and their objectives and priorities often at loggerheads with the commonwealth. Such facts don't seem to trouble most bourgeois economists, who continue to research and write about economics from the favored perspective of their corporate patrons. Magnuson's text seeks to correct that focus, and return it to its proper place:

"It is rather shocking," says Magnuson, "that so little is written from the perspective of the billions whom this system damages every single day, or from the perspective of the planet it is destroying at an accelerating pace."

Magnuson is talking here about the central question of all economic, nay, all human activity: cui bono? Is the "economy"—this abstract entity we have been taught to respect as determined by inviolable natural laws—the servant of society (i.e., the vast majority), or the other way around? Do we work to make it happy, propitiate it as a whimsical god, or does it work to make us happy? The record is peculiar to say the least. To even have to pose the question is perhaps a reflection of how far we have strayed from common sense. The signs of the disorder are everywhere.

Man-made cultural fog

ven allowing for the widespread (and shameful) economic illiteracy among media people, and the fact that even those who should know better are more interested in advancing their careers by dispensing lies and "getting along" with their bosses than telling it like it is, it's still amazing to observe the near unanimity with which in contemporary capitalist culture all manner of measures negatively afflicting the interests of the average citizen are routinely described as "necessary" and for "the good of the economy." No one ever poses the obvious question of why the vast majority of human beings must submit to the tyranny of this abstract Molloch, whose triumphs over the masses invariably bring Wall Street to paroxysms of delight.

David Ricardo, one of the great classical political economists. He might have been surprised—maybe shocked–by the irrelevancy of so much modern economics to the public interest.

Many readers of this essay may have probably noticed that under this curiously perverse economy, human happiness and the happiness of the markets seem to be perennially at loggerheads...apparently entangled in a cosmic zero sum of Olympian proportions. When unemployment grows, Wall Street cheers. When factories are closed, or relocated to cheap-wage regions, when pensions are slashed, or stolen, when laws to protect the workers or the environment are defeated, when whole industries are taken over by opportunistic raiders...in sum, when human and planetary misery increase, or promise to increase...corporate valuations jump off the charts and a merry choir of mavens come out of the woodwork to celebrate the good news and help break out the champagne. If you think this spectacle is a bit insane, you're right. It is insane. Why do so many people, otherwise intelligent people, put up with such things? That, again, is where false consciousness and misleading instruction come in—reinforced by the cumulative sense of powerlessness that an "atomized" existence usually engenders. They present as logical and inevitable even what is none of those things. So perhaps the urgent but still unasked question is this: just what is this mysterious "economy"? The truth emerges when we look behind the veil.

Omissions, falsehoods, shortcomings, and mystifications

found in mainstream economics

Although the subject is vast—and fairly technical at times—in chapter after chapter, Magnuson's book helps the reader understand and question a large number of issues, and in so doing better comprehend the magnitude of the imposture represented by economics as taught to this day in most colleges across the Unites States and much of the world. For starters, Magnuson does not pretend to be analyzing some "universal and immutable laws of economics," forever true for all nations and epochs, but merely the anatomy of contemporary American capitalism, warts and all. Let's review a few topics that cry for (but never receive) proper attention.

Four major themes underscore Mindful Economics' panoramic view of capitalist activity:

this is a non-negotiable feature that defines it. You can make a man agree to many things, but you can't negotiate with him to stop breathing. That's a non-negotiable demand. Same with capitalism and growth. Constant growth is buried deep in the dynamic of capitalism and now in its mature executive sociology. It's not subject to negotiation. Yet —as anyone, except capitalist diehards and those influenced by them can see—eternal growth is impossible in a finite planet that is growing smaller all the time, especially against the backdrop of continually expanding human populations. Thus, a system like capitalism, that posits endless economic expansion in a finite planet, is insane, by definition.

• Capitalism, a highly hierarchical, inegalitarian system did not clash with the exploitative values of feudalism. It merely forced it to amplify its privilege sphere to embrace the rising class of rich merchants and bankers—the bourgeoisie. Given this value orientation—and when we put self-serving propaganda aside—capitalism can be clearly perceived as inherently indifferent and even hostile to democracy. Capitalism simply thrives in right-wing dictatorships. Chomsky calls capitalist structures "tyrannies" and he's not exaggerating.

• As time goes by, the capitalist crisis can only worsen—the disappearance of jobs, environmental degradation, deeper recessions and inequality, antisocial production, etc.—grows in intensity and there is no possible cure within boundaries acceptable to the capitalist class. This crisis is a direct result of capitalism's core dynamic, and its social relations.

That may be desirable for this tiny minority, but for the rest of us the only cure for capitalism is to transcend it. Space constraints do not allow an in-depth discussion of these issues and their numerous ramifications, many of which are treated in an extremely lucid format by Magnuson, but a short examination may suffice here for the reader to get a sense of what is involved.

The scandal of the GDP Fetish

From Lou Dobbs to Alan Greenspan, to the regular business class teacher, the media "expert" trotted out to "explain the economy," the corporate executive, or politico on the stump, the mantra is always the same: the GDP is a good barometer of the nation's economy, and it better be growing. But this worship of the GDP [Gross Domestic Product] as a reliable yardstick for general social well-being, intimately connected to the growth obsession, is just one of the multiple ways in which bourgeois economics contributes to the miasma of false consciousness. The operating assumption is that there's a close correlation between constant economic growth and increases in the quality of life for all, although there are several enormous flies in this lovely ointment.

To begin with, a bigger GDP does not automatically mean a better life for the vast majority. The truth depends on how the national income is being distributed and (equally important) whether the "goods" counted as positive entries in the economy are real, tangible additions to the well-being of the population. Forget the fabled "trickle down" effect and "the lifting of all boats" economic rapture expected to take place when the superrich are allowed to get away with practically anything. Unadulterated poppycock. A smaller pie in which everyone gets a fair share is probably much better than a much larger pie in which 5% of the top take 90% of the pie. What's more, averages, so widely used in official statistics, lie.

Consider a society comprised of two people. One has an income of $1 million dollars. The other, only $1,000. The average income indicator would tell us that both are doing terrific, at $500,500 each. This is an extremely simplified snapshot, a fantasy if you will—who ever heard of a nation comprised of only two people—but the lesson is true insofar as the application of the sacred tools of mainstream economics are concerned. Worse still, the GDP takes no account of infamous externalities: mounting social inequality, widespread environmental pollution, damage to people's health as a result of industrial practices, or lethal threats to the planet itself. It's also stubbornly blind to the many realities that underscore the best things in life not only for us, but for every sentient creature on earth—like the pure oxygen that a beautiful tree quietly affords us, or the advantages, let alone wonderfulness, of clean rivers and oceans—while it computes as "gains" things that in actuality represent tragedy and loss. Thus a crackup on the highway resulting in a demolished car and someone's death or somebody's prolonged hospital stay, turns up on the capitalist ledgers as income generated for hospitals, doctors, nurses, drug companies, garages, funeral parlors, and car dealerships. Similarly, the GDP robotically celebrates any construction, whether it be of prisons or family homes. And following the same blind logic, it treats crime, divorce and other elements of social breakdown as economic gains. It's a measurement model in urgent need of revamping.

As previously said, measuring all economic and societal "success" by a corporate yardstick of constant growth, capitalism suffers from a compulsion to expand infinitely in what is clearly a very finite and ailing world, thereby betraying in its dynamic something akin to systemic madness. Expansion at all costs is fueled by a well-developed culture of 'short-termers"—the notion of a true capitalist statesman is an oxymoron—and a self-perpetuating, self-selecting, macho executive sociology according to which career advancement is only possible on the basis of--again--constant growth, plus aggressive competition in the boardroom jungle.

Unfortunately for society, these so-called "captains of industry"— like the political class they resemble and own—are characterized by having as much power as obtuseness. The world will not be led out of the crisis by them because, to recall Herzen's famous dictum, "they are not the cure, they're the disease." For them and for us, the tragedy is that they will never admit the enormous flaws in their favorite system, because in their hubris they can't see the actual consequences of their actions, never will, and probably don't care. Such acquired selective blindness, of course, the product of multiple layers of insulation from reality on the back of obscene wealth (one more demonstration of existence and character determining consciousness), doesn't mitigate the fact that the earth is being destroyed at a rapid clip, human-caused species extinction is at an all-time historical high and accelerating, many cataclysmic wars are in the offing (over deeper and vaster exploitation of human and natural resources), while and immoral industrialism continues to extend itself over the planet like an unstoppable raging cancer. Quite an accomplishment, for an species that only "yesterday", in geologic time, climbed out of the primordial soup.

Correctly sensing the importance of this topic, Magnuson devotes two of Mindful Economics' core chapters—Chapter Eight ("The U.S. Capitalist Machine") and Chapter Nine ("The Growth Imperative") to its examination. He is resolute in his rejection of the GDP growth theology:

GDP is the premier measure of the economic machine's performance and growth of GDP is heralded as a supreme virtue... It is rare to find an economist who would question this virtue of economic growth as a positive contribution to human well-being. Yet, GDP growth masks other indicators that would suggest that its ongoing growth is not necessarily good for human well-being...GDP is the dollar value of all finished goods and services produced in an economy in a year's time. As a single number, roughly $10 trillion [in the U.S.], it is a numerical measurement expressed as an undifferentiated mass of products and services. GDP does not take into account under what conditions the products and services are produced, whether they actually improve people's lives, the damage done to people and our environment resulting from growth, or how the output is distributed among the population. [W]]hen we attempt to reduce something as complex as a measurement of well-being of an entire population to a single number, much important information falls through the cracks. (ME, p. 193)

Naturally, the GDP error is far more serious in a deeply class-divided society such as the United States, where huge canyons of inequality separate different layers of the population. But even if we treated a fairly egalitarian capitalist society (something of a contradiction in terms) the blindspots would continue, for, as Magnuson indicates, the problem is that the GDP is calculated in a way "that is heavily biased toward capitalist production." The meaning of that can be gleaned from the following:

Although GDP imputes some value that is created in the public sector, it primarily measures the dollar value of transactions that only occur in the capitalist marketplace. The capitalist machine will appear to be slowing down when people prepare their own meals, clean their own homes or do their own yard maintenance rather than pay businesses in the private sector to perform the same work. If people grow food in their own vegetable gardens, there is no change in GDP, but if they buy those same vegetables in a grocery store GDP rises. (ME, p. 193)

Milton Friedman: Unswerving priest of free-market fundamentalism. "Both the rich and the poor can sleep under the bridges if they want."

Unsolvable issues: ecological sanity, instability, social justice

As the preceding discussion suggests, the capitalist system suffers from enormous contradictions and compulsions not liable to be resolved within the framework of policy permitted by the system's chief beneficiaries. Most importantly, capitalism, as indicated previously, is a system that by design is on a lethal collision with nature. Endless expansionism is buried deep in its genes. (Joel Kovel, a "green economist", justly called his own 2002 volume, The Enemy of Nature). Can anything be done?

The growth mania is not likely to be abandoned any time soon, nor moderated in a manner satisfactory for ecological health. Besides the established requirements of constant competition, the by now well-entrenched "executive mentality" mentioned above (a sociological superstructure in its own right) is turbocharged and replicated at every turn by the catechism taught in business schools, Western madrassas of business fundamentalism where far too many eager youths, not particularly burdened with too many moral scruples, converge to learn how to become Gordon Gekkos in the shortest possible time. Furthermore, the ever-expanding pie has some other less well discussed functions, such as social pacification (constantly rising income however minimal dampens cries for egalitarianism), and what some have called "redistribution of income at the margin" whereby huge transfers of wealth are effected from the middle and lower classes to the top with few if any ever noticing. This is however a delicate mechanism. Let the economy grind to a halt, or backslide, and the true face of Dorian Gray begins to show.

But if growth is non-negotiable, what about the other classical areas of social contention? Perhaps as a result of the tensions and popular resistance triggered by the push for globalization, and lately global warming, the last couple of decades have seen the rise of a new wave of "cosmeticization" of capitalism (in the 1970s it was "people's capitalism"), and this time the snake oil salesmen are saying that the problems of the market system—from economic instability to inequality, to jobs evaporation, and ecological destruction—can be neutralized through a technological fix according to which "everybody wins." The new golden byword is "sustainability." Magnuson devotes his closing chapters to puncturing this manufactured illusion.

Under the capitalist mode of production [and consumption], the purpose of economic activity is to make and accumulate profits. Respect for nature and humanity—critical elements for any sustainable system—may or may not occur depending on whether it is consistent with profit-making. The historical evidence is overwhelmingly clear that these purposes are not consistent, and are in fact opposite. (ME, p. 344)

Yes, social justice and an enlightened, generous attitude toward nature, away from dominionistic dogmas, what Magnuson calls a "respect for nature and humanity" are the foundation of a durable and highly stable economy. Problem is, they just can't happen under capitalism, or any other form of myopic, highly hierarchic, backward-looking system. And technology, per se, while important, is peripheral to this equation. For, as Magnuson is quick to add, "although technology can lighten people's ecological footprints, it does not solve the core problem associated with capitalism."

Some folks will surely take exception to this assertion, considering it a simple instance of leftist "extremist" thinking, or "radical environmentalist" bias. This is to be expected because far too many people, "rather than face the need for systemic change...prefer to believe in 'win-win' fallacies that suggest the capitalist system can be preserved and at the same time achieve the Three Es of sustainability."

The "win-win" fallacy attempts to connect the Three Es of ecology, equity, and economy to the compulsive dynamic of capitalism, chiefly its unrelenting drive for profits. In that manner it chooses to believe "that we can achieve ecological sustainability without compromising corporate bottom lines." As Magnuson notes, this has become a popular approach to selling the business community the notion of sustainability (which their own p.r. hacks have long advocated) but the foundations are shaky:

This brings to mind the old fallacy about the exceptions that always exist in any class or group of people larger than three. There have always existed lords who treated their inferiors with some humanity, entrepreneurs who took care of their employes ("paternalistic capitalism") and slaveowners who eventually granted their slaves their freedom. In fact, as two recent films, Schindler's List and The Pianist so forcefully implied, even the Nazis had a few good apples. But the problem presented by exploitative groups and classes is never in the exception but in the rule, which remains overwhelmingly toxic. The crux of the matter, as ME makes clear, is that,

To the impartial observer the poverty of bourgeois economics is pretty much irrefutable. It cannot offer any better solutions to the great issues facing humanity in the 21st century than it did in the 20th and 19th centuries. The promises of a lasting prosperity on the basis of "an administrated capitalism" using the toolbox of Keynesianism came crashing down with the end of the postwar "Long Boom" in the 1970s, and the onset of stagflation. Today all that really remains is a melange of Friedmanism and military Keynesianism, without which the system could not possibly survive. Endless war is not only grotesquely profitable to the weapons manufacturers and associated constituencies, it is indispensable to the viability of the modern capitalist state, and essential to the new global empire. Meanwhile, the noose keeps tightening around the system's neck. Automation will go on erasing jobs in all continents (China already has more than 100 million effectively unemployed) until the ultimate absurdity of the system will be revealed to all: a handful of people will produce a mountain of goods that only a handful of plutocrats can consume. The rest will be simply "superfluous" to the capitalist logic.

Capitalism has always drowned and faltered on its unjust social relations. The outrageously lopsided way it distributes income, the product of society, continually augmented by advances in technology, is a contradiction that has no economic answers because it is really a question of power, a question of politics. The constant elimination of jobs by automation, and their hemorrhage toward cheap-labor zones cannot be "cured" by job training programs or even better education for all (as Clinton cabinet member Robert Reich, the main evangelist for this pseudo-solution, used to preach). An advanced degree is no guarantee of employment in a job market that has no need for 100,000 applicants with such uber-credentials. The drift toward authoritarianism cannot be arrested, only slowed down or momentarily interrupted given the essentially undemocratic nature of the system. As we said earlier, living with capitalism is like living with a sociopath in the room, a maniac who bears constant watching.

In a recent article, my colleague Susan Rosenthal wrote:

By 2000, U.S. workers took half the time to produce all the goods and services they produced in 1973. If the benefits of this rise in productivity had been shared, most Americans could be enjoying a four-hour work day, or a six-month work year, or they could be taking off every other year from work with no loss of pay. (See, Globalization: Theirs or Ours?)

These are the central questions that "economics" should be debating, that students should be pondering. But Samuelson, Friedman, Von Hayek and their numerous descendants throughout academia (and media) are silent on these issues, as they know only too well that to analyze them with scientific honesty would be to prepare an indictment of capitalism.

By departing from such a shameful tradition of accommodation to the system, a book like Mindful Economics performs a signal service to society, as it arms people with the kind of knowledge they need to see through these multiple falsifications. Only the defeat of the prevailing false consciousness, to which orthodox economics has contributed so much, can open the road to a solution of the current crisis.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License