Special Report: In recent years, the Washington Post’s emergence as a neocon propaganda sheet has struck some as a betrayal of the Post’s earlier reputation as a serious newspaper. But many of the paper’s current tendencies can be traced back to its iconic editor Ben Bradlee, writes James DiEugenio in Part 2 of this series.

Ben Bradlee’s journalistic reputation is defined in the public’s mind by his role as the Washington Post’s gutsy executive editor during the Watergate scandal and especially by Jason Robards’s dramatic portrayal of him in the movie, “All the President’s Men.” Bradlee’s role in Richard Nixon’s political demise and his famous friendship with John F. Kennedy created an image of Bradlee as an icon of the “liberal media,” but those chapters of his life are misleading and miss the point of who Ben Bradlee really was and what his legacy truly is.

As we saw in Part One, Bradlee came from the American ruling elite and operated within a social framework that involved close personal relationships with leading figures in the U.S. government and its intelligence community, including CIA rising star Richard Helms who had been Bradlee’s friend since childhood.

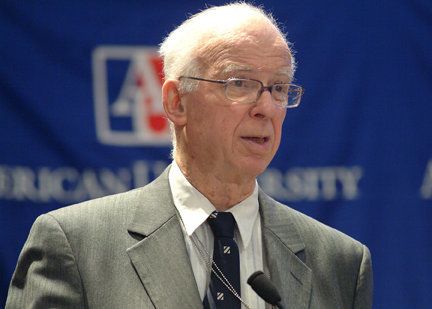

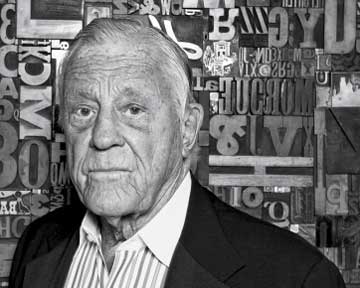

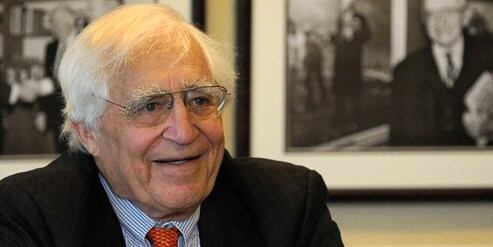

The Washington Post’s Ben Bradlee in his later years. (Photo credit: Washington Post)

In the 1950s, Bradlee not only worked as a U.S. government propagandist in France with close ties to Operation Mockingbird, the spy agency’s project for penetrating and influencing the U.S. news media, but he developed close personal ties to the CIA’s Cord Meyer, a senior clandestine services propagandist considered a leader of Operation Mockingbird.

Meyer and Bradlee each married sisters from the same well-to-do family, Mary and Tony Pinchot, respectively. Tony Pinchot took up with Bradlee after she met him in Paris where he was working as Newsweek’s bureau chief. She and Bradlee then divorced their spouses and married in 1956.

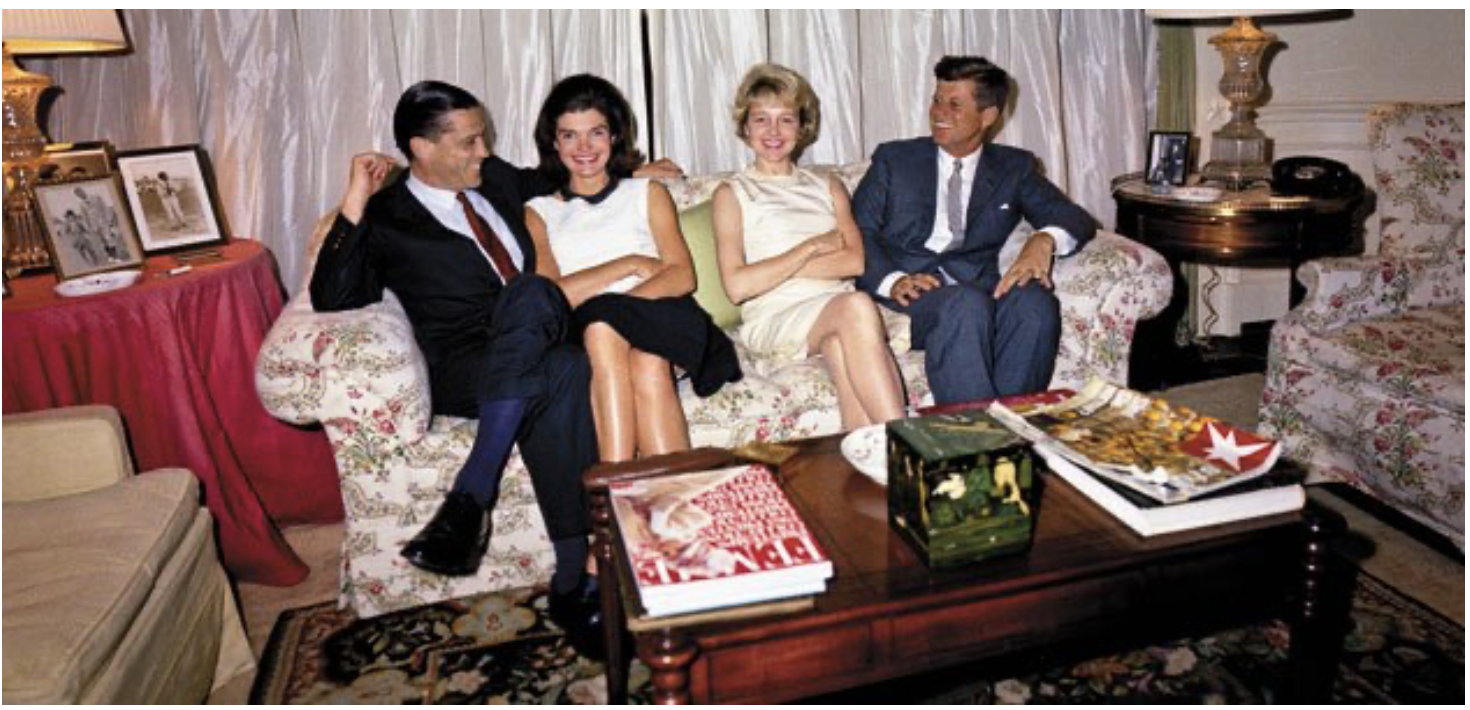

After the couple moved to the pricy Georgetown section of Washington, they socialized with the great and powerful, including two other glamorous neighbors John and Jackie Kennedy. Bradlee was a Newsweek political correspondent and then the magazine’s Washington bureau chief. So these relationships, which sometimes bordered on the incestuous, served him well as he rose through the ranks of the Washington news media.

Cord Meyer and wife, Mary Pinchot.

Cord Meyer, then Bradlee’s relation through marriage, was himself a close friend of James Angleton, the legendary and sinister CIA chief of counterintelligence. The two men’s wives, Mary Pinchot Meyer and Cicely d’Autremont Angleton, were very close and remained so even after Mary Meyer divorced Cord Meyer in 1958. Later, Mary Meyer was widely rumored to have had an affair with John Kennedy, a relationship that supposedly continued until Kennedy’s death on Nov. 22, 1963.

When Mary Meyer herself was murdered on Oct. 12, 1964, along the Georgetown towpath, it was Ben Bradlee who was called by police to identify the body of his sister-in-law. Afterwards, Bradlee encountered Angleton entering the slain woman’s Georgetown house and then joined the CIA counterintelligence chief in a search for her personal diary, not to reveal its contents but to hide whatever secrets were in there.

According to an FBI document, James Angleton, Bradlee’s fellow searcher, and Richard Helms, Bradlee’s boyhood chum, canceled a meeting on Oct. 14, 1964, because they were deeply involved in matters surrounding Mary Meyer’s death.

As for Mary Meyer’s mysterious diary, the Washington Post’s 2011 obituary of Tony Bradlee, Mary Meyer’s sister and Ben Bradlee’s second wife, noted that “Mrs. Bradlee subsequently found the diary, which appeared to disclose her sister’s affair with late President John F. Kennedy. Mrs. Bradlee and her husband, who was serving as head of Newsweek’s Washington bureau, turned the diary over to Angleton with the promise that the CIA would destroy it.

“More than a decade later, Mrs. Bradlee was upset when she heard Angleton had not kept his word. Through an intermediary, she got the diary back and set it on fire.”

A half century after her death, Mary Pinchot Meyer’s murder is still listed as unsolved and the contents of her diary remain an enduring Washington mystery, prompting speculation regarding what it might have revealed about powerful people in both the political and intelligence worlds. [These lingering mysteries have been the subject of two books, Nina Burleigh’s A Very Private Woman (1998) and Peter Janney’s Mary’s Mosaic (2013)]

Mr. Insider

So, the image of Bradlee as a hard-bitten, tough-talking newsman who put the inner workings of the U.S. capital under a microscope and then shared those details with the American people, without fear or favor, was never the reality. Bradlee was an insider who may have exposed some wrongdoing as he wielded the Post as a weapon against certain political enemies but not as a sword fighting for the unbiased and unvarnished truth.

In Bradlee’s elite world, it was best to keep some of Washington’s secrets locked away from those who might not understand what was “good for the country.” Or as his boss and benefactor Katharine Graham once noted in a speech at CIA headquarters, “We live in a dangerous world. There are some things the general public does not need to know and shouldn’t. I believe democracy flourishes when the government can take legitimate steps to keep its secrets and when the press can decide whether to print what it knows.” (Counterpunch, July 25, 2001)

The reality about Ben Bradlee’s elitist attitude toward journalism that it is more about guiding the people than informing them is underscored by his first major hire after he became the Post’s managing editor in 1965. That hire was David Broder, then a political reporter in the New York Times’ Washington bureau whom Bradlee had heard was frustrated with his editors at the Times. (Himmelman, p. 109)

Bradlee made it a prime objective to hire Broder away from the Post’s perceived rival as a top national news publication and he was proud of succeeding. Broder and his political columns would remain a fixture at the Post almost until the end of his life in 2011.

Broder: Established vermin as respected pundit. "War with Iran will be good for the economy."

Yet, Broder came to typify all that was wrong with mainstream journalism as he would regularly recite the capital’s conventional wisdom and rarely rock the boat. Broder’s style of journalism said a lot about who Ben Bradlee really was and where he wanted to take the Post.

As the Internet began to grow in the 1990s and then explode in the new millennium, many bloggers expressed their annoyance and anger at the MSM by singling out Broder and his tedious insider reporting. In fact, a new term was coined “High Broderism” which meant a long and dilatory paragraph that, once analyzed, said either very little or nothing, a gaseous obfuscation that had one objective: to defend the status quo.

In fact, toward the end of Broder’s career, even some liberal members of the MSM had had enough of his pompous punditry. Hendrick Hertzberg of the New Yorker called him “relentlessly centrist.” (April 14, 2006) Frank Rich called him the nation’s “bloviator in chief.” (Politico, Dec. 19, 2007)

Broder was so much of an insider that he began collecting hefty lecture fees from industry groups and then lobbied Congress on behalf of at least one of those groups, even though this was a clear violation of the Post’s editorial policy. He then appears to have lied about it by saying it was cleared in advance. (Harper’s, June 12, 2008)

By hiring Broder and then maintaining the columnist as a fixture at the Post for over four decades, Bradlee not only showed what kind of protect-the-Establishment journalism he valued but that he was blind to the media future that was just over the horizon.

Another early and revealing Bradlee hire was Walter Pincus, who was actually hired twice, once in 1966, and again after he left The New Republic in 1975. As a national security reporter, Pincus was another consummate insider, as much a trusted part of the U.S. intelligence community as a reporter covering it.

To say that Pincus (left) has had a controversial career does not begin to describe the man. He started on CIA subsidy by spying on students abroad. (Gary Webb, Dark Alliance, pgs. 464-66) Covering the Watergate hearings for The New Republic, Pincus appears to have gotten private access to Richard Helms. (See a story Pincus wrote for the Post at the time entitled “The Watergate Decoy” on July 22, 1974)

To say that Pincus (left) has had a controversial career does not begin to describe the man. He started on CIA subsidy by spying on students abroad. (Gary Webb, Dark Alliance, pgs. 464-66) Covering the Watergate hearings for The New Republic, Pincus appears to have gotten private access to Richard Helms. (See a story Pincus wrote for the Post at the time entitled “The Watergate Decoy” on July 22, 1974)

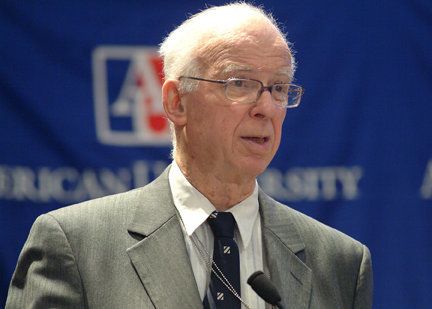

In 1975, Pincus was fired as executive editor of The New Republic, which was then a fairly liberal publication, and went back to the Post, where he said of the newly formed House Select Committee on Assassinations, that it was “perhaps the worst example of congressional inquiry run amok.”

During the Iran-Contra inquiry of the late 1980s and early 1990s, Pincus reported that Independent Counsel Lawrence Walsh was going to indict Ronald Reagan, which turned out to be false. Walsh later wrote in his book Firewall that this phony story hurt his investigation more than anything else. Finally, and predictably, it was Walter Pincus who began the attack in 1996 against Gary Webb’s sensational exposé of the CIA and drug running.

Shifting to the Right

As executive editor beginning in 1968, Bradlee brought onboard other writers who would help define Official Washington’s conventional wisdom in a way that protected the powers-that-be and punished anyone who challenged the Establishment’s version of events.

It was under Bradlee that editorial writers such as Richard Cohen (who began as a reporter in 1968), George Will and Charles Krauthammer first gained national notoriety. The latter two showed how the Post would seek out and then offer conservative writers at smaller publications The National Review and The New Republic a bigger platform to reach the broad American public and thus help set the national agenda. In the case of Krauthammer, both he and The New Republic had clearly turned hard to the right by the time the Post began carrying his column in 1985.

Bradlee also was hostile toward journalists whom he perceived as being more iconoclastic and less inclined to revere the powers-that-be. For instance, before the Watergate scandal, Bradlee wanted to fire Carl Bernstein. (Davis, p. 250)

Looking back at Bradlee’s long career as an editor and then an executive at the Post, it is hard to find any liberal opinion maker or reporter that Bradlee discovered or fostered. (Joseph Kraft was first hired by publisher Phil Graham, while Ben Bagdikian left the Post partly because he did not understand where Bradlee’s editorial policies were headed.)

Despite Bradlee’s JFK-Watergate connections, there is substantial evidence that what Bradlee encouraged and indeed accomplished was to move the Post systematically to the right, making it what it is today, the nation’s neoconservative flagship promoting a militaristic global agenda for the United States.

As stated at the end of Part One, one of the odd things about Bradlee’s career since 1963 is that he never tried to defend his friend John Kennedy against some of the false accusations made against his administration. A common one being that President Johnson was just continuing Kennedy’s policies in Vietnam.

Did Bradlee read the Pentagon Papers that the Post joined in publishing in 1971? If not, he might have at least read about the revelations regarding Kennedy’s intent to wind down the Vietnam War before he wrote his 1975 book, Conversations with Kennedy.

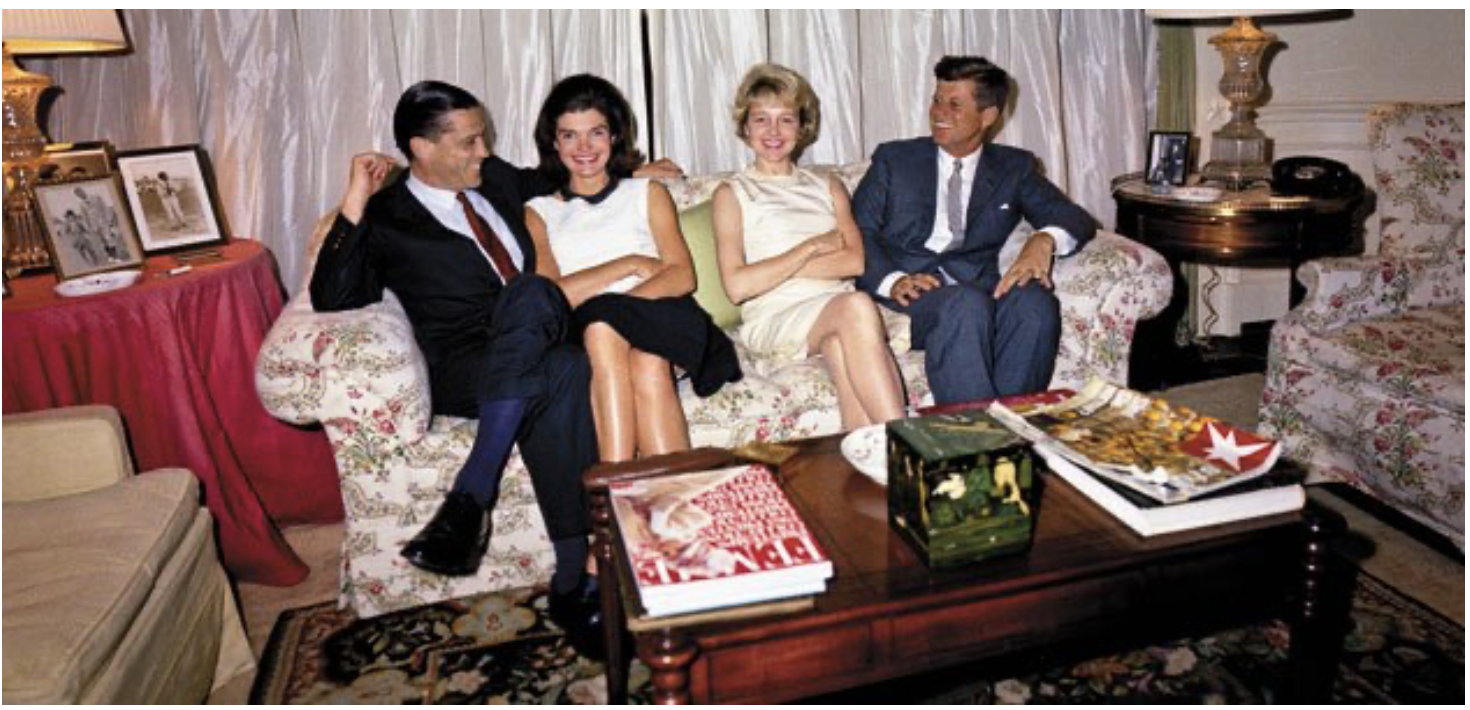

Before discussing Conversations with Kennedy, it should be noted that Ben Bradlee had been friends with President Kennedy for at least five years before Kennedy was killed. They also dined together at the White House on many occasions as well as visiting each other’s homes and sharing drinks and conversations at least twice a week. There is no other journalist whom Kennedy was as close to as Bradlee and Bradlee and his wife continued a relationship with Jackie Kennedy after her husband died.

Ben Bradlee (left) and his then-wife Tony Bradlee (second from right) with President John and Jackie Kennedy after a White House function. (Photo credit: JFK Library)

But Bradlee did not write his book until 1975, a dozen years after Kennedy’s death. So in addition to his own source material, there were many books that Bradlee could have consulted about both Kennedy’s career and his assassination.

In reading Conversations with Kennedy today, it’s obvious that Bradlee did none of this. In fact, he spent about as much time and effort on the book as a college sophomore would spend on a research paper: three weeks. (Himmelman, p. 299)

Not only is the book breezy and shallow, it is simply wrong in many places. For instance, Bradlee writes that Kennedy was not really interested in foreign affairs when he was running for president and that Kennedy’s presidency was more flash and dash than it was substantive which by the mid-1970s was the conventional wisdom emerging to denigrate Kennedy’s presidency. (Conversations with Kennedy, pgs. 12, 41).

Worthless Book

Reading those two comments shows how worthless Bradlee’s book is today because as many writers have revealed, Kennedy was not just interested in foreign policy, he was remolding the very structure of American foreign policy in a rather revolutionary way. He was reversing the militant Cold War trends created by Harry Truman and reinforced by the Dulles brothers under Dwight Eisenhower.

Kennedy was doing this in many places, but especially in the Third World. For example, during the 1960 campaign, Kennedy mentioned Africa 479 times. (Philip Muehlenbeck, Betting on the Africans, p. 38) As chairman of a subcommittee on Africa, Kennedy was eager to see the continent become independent and free from both colonialism and imperialism.

This was a stark break from what the Eisenhower/Nixon administration had done. For instance, at an NSC meeting, Nixon said some of the people of Africa “had been out of the trees for only about fifty years.” Thus, it was only natural that Nixon would back political strong men in Africa and oppose the development of any viable left through labor unions and other social movements. (ibid, pgs. 6-7)

Yet, within weeks of his Inauguration, Kennedy reversed the prior Eisenhower-Dulles policy in Congo where U.S. and neo-colonial forces had opposed a leftist anti-colonial movement, although it was too late to save revolutionary leader Patrice Lumumba who was shot to death on Jan. 17, 1961, three days before Kennedy took office. [See Consortiumnews.com’s “JFK’s Embrace of Third-World Nationalists.”]

Despite Bradlee’s JFK-Watergate connections, there is substantial evidence that what Bradlee encouraged and indeed accomplished was to move the Post systematically to the right, making it what it is today, the nation’s neoconservative flagship promoting a militaristic global agenda for the United States.

Therefore, for Bradlee to write that in 1960 Kennedy was some kind of neophyte in foreign policy and deferred to Nixon in that field makes one wonder how well the author knew Kennedy or question the integrity and honesty of the book.

For instance, Bradlee informs us that he was appalled that Kennedy had discussed with the CIA the possibility of staging a student demonstration in the Dominican Republic. Bradlee adds that he vocally objected to this and was surprised that Kennedy would countenance such interference in a sovereign state’s internal affairs. (Conversations with Kennedy, p. 235)

Recall that Bradlee was the man who worked hand in glove with the CIA for three years in France and played a key role in preparing the European public for the electrocution of the Rosenbergs. Bradlee also leaves out some rather crucial background facts about this dialogue with Kennedy.

First, the Dominican Republic was coming out of decades of brutal repression under the bloodthirsty dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo. In February 1963, the country had elected the liberal socialist Juan Bosch as president. Kennedy had backed Bosch and wanted to extend him loans for development through the Alliance for Progress.

But Bosch was overthrown by the military in September 1963, prompting Kennedy to begin a hemisphere-wide campaign to restore Bosch to power. Kennedy broke diplomatic relations with the military junta and suspended economic aid. He then ordered all U.S. military and economic assistance agents to return home. Other countries in the area joined Kennedy in condemning the overthrow, e. g., Mexico, Bolivia, Costa Rica. The junta complained about Kenney’s harshness and like Ben Bradlee said the U.S. president was interfering with the country’s affairs. (Donald Gibson, Battling Wall Street, p. 78)

But this context of how Bradlee favored a dictatorship over a democratically elected president is not the worst of what he leaves out. The Kennedy/Bradlee conversation took place in early November 1963 when because of Kennedy’s support Bosch had increased his chances of returning democracy to his country, a process that continued even after Kennedy’s death.

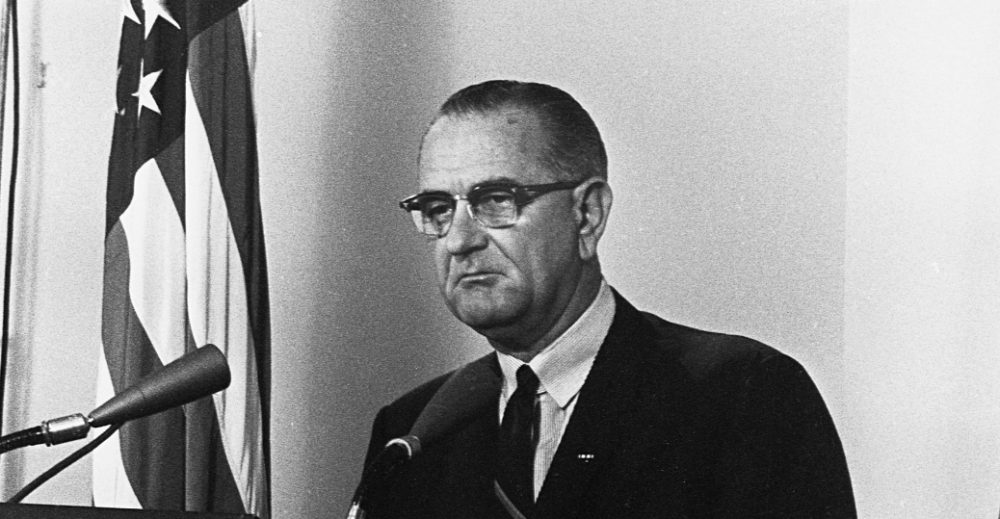

In early 1965, it looked like Bosch was about to succeed. However, President Lyndon Johnson decided to intervene with the Navy and Marines and portrayed Bosch and his followers as communists to justify the unilateral American intervention. (ibid, p. 79)

The Marines stayed in the Dominican Republic for a year and supervised new elections in which Joaquin Balaguer, a former friend and political ally of Trujillo, took power. This reactionary intervention was one of several that Lyndon Johnson, Katharine Graham’s friend, implemented in reversing Kennedy’s policies around the world. But Bradlee does not inform the reader of this background. After all, Katharine Graham was his boss at the time.

Ignoring Vietnam

For the most part, Bradlee ignores the issue of Vietnam, but he brings it up in a jarring way near the end of the book. Bradlee tells us that Kennedy, while reading the Washington Post one day, noticed a photo of American soldiers in Saigon dancing with local prostitutes. The President complained that it looked like a put-up job by the Associated Press and called the State Department to do something about it. Bradlee, who was still at Newsweek, overheard JFK saying: “If I were running things in Saigon, I’d have those GIs in the front line the next morning.” (Conversations with Kennedy, pgs. 234-35)

LBJ—A complex man with a stubborn chauvinist streak

Again, Bradlee wrote the book in 1975 as the Johnson/Nixon escalation debacle was finally concluding. There had already been some writing about Kennedy’s intent to withdraw from Vietnam by this time. In addition to the Pentagon Papers, there was an essay by Peter Scott in Ramparts in 1971 and the book by Kenny O’Donnell and Dave Powers, Johnny We Hardly Knew Ye, which was quite specific in pointing out that Johnson had reversed Kennedy’s intent to withdraw. We know this had been made explicit with Kennedy’s National Security Action Memorandum 263 in October 1963. Again, the Bradlee/Kennedy dialogue took place in November 1963, after NSAM 263.

Therefore, Kennedy must have forgotten that it was he who was controlling things in Saigon. He had just steamrolled his advisers into going along with him on this withdrawal order. (See John Newman, JFK and Vietnam, pgs. 404-07) Kennedy’s policy was reversed by Johnson shortly after Kennedy’s assassination with NSAM 288 which drew up formal battle plans for committing combat troops to Vietnam in March 1964.

Though Bradlee is often described as an overly close friend of JFK some conservatives have demeaned Bradlee as JFK’s “coat holder” he appears to have had a surprisingly cold and disinterested attitude toward his “friend’s” murder.

In Conversations with Kennedy, Bradlee described meeting the bereaved Jackie Kennedy when she returned to Washington from Dallas. Bradlee noted that the widow was glad to see him and his wife and then recounted her fresh recollections of the shooting to him, possibly the first time she had discussed it with someone outside government.

“I can remember now only the strangely graceful arc she described with her right arm as she told us that part of the president’s head had been blown away by one bullet,” Bradlee wrote. (p. 242)

Yet, Bradlee seemed to miss the significance of this as he wrote it in 1975 because by then the autopsy materials had been made available to scholars and the damage from the fatal head shot with parts of the skull blown backwards had contributed to growing doubts about the Warren Commission’s conclusion of only one shooter, Lee Harvey Oswald, from behind.

What Jackie was describing was either the Harper fragment — a large part of the rear of the skull recovered in Dealey Plaza a day later — or a smaller fragment which we see her reaching for out the back of the limousine in the Zapruder film. Both of these were indicative of a shot from the front.

Ben Bradlee, Newsweek’s Washington bureau chief at the time, heard this from the person closest to Kennedy in the car and sat on it for more than a decade. Which brings up an issue that, oddly, no one has ever pointed out about Bradlee and his relationship with Kennedy. Many, especially on the Right, have tried to insinuate that somehow Bradlee was biased in favor of JFK. Yet, as one can see from reading Conversations with Kennedy, such was really not the case.

Wasting an Opportunity

Secondly, there was probably not a journalist in America who was in a better position to investigate the strange circumstances of Kennedy’s death than Bradlee. He had been lifelong friends with Dick Helms, who was coordinating the CIA inquiry into the assassination for the Warren Commission.

Helms was a friend and colleague of former CIA Director Allen Dulles, who was appointed to the Commission by Lyndon Johnson and was its most active member. Dulles attended the most meetings, interviewed the most witnesses, and asked the most questions. (Walt Brown, The Warren Omission, pgs. 87-89)

Through his mother, Bradlee had connections to the law firm of John McCloy, another very active member of the Commission. Bradlee also was the neighbor of Mary Pinchot Meyer, Cord Meyer’s ex-wife who was very close to Kennedy and was rumored to have been his mistress. Through the Meyer family, Bradlee had access to James Angleton, the chief of CIA counterintelligence with whom Bradlee searched for Mary Meyer’s diary after her death less than a year later.

If that weren’t enough, Bradlee still had good relations with Robert Kennedy as well as Jackie Kennedy. As David Talbot discussed in his book Brothers, and as Bobby Kennedy Jr. later revealed to Charlie Rose, Robert Kennedy never bought the official story about JFK’s murder.

In fact, as first revealed by Tim Naftali and Aleksandr Fursenko in their book One Hell of a Gamble, Bobby and Jackie sent a post-assassination message to the Soviet hierarchy via Georgi Bolshakov, a KGB agent who had formerly been stationed under cover in Washington.

William Walton, a close JFK friend, told Bolshakov that the Kennedys believed the President had been victimized by a large political conspiracy, and although Lee Oswald was billed as a communist who had defected to the Soviet Union, they did not think the plot was a foreign one. At the time, Robert Kennedy was already planning to quit as Attorney General and run for political office with an eye on the White House and toward resuming JFK’s pursuit of detente with Moscow. (Talbot, p. 32)

In other words, if Bradlee needed any backing to begin his own investigation of the assassination, the Kennedys would have given it to him. Bobby could have helped provide him entreé to the Warren Commission via Nicolas Katzenbach, his deputy, who was the Justice Department liaison to that body. They also would have let an expert of his choice privately view the autopsy materials.

RFK would have granted Bradlee access to men like Ken O’Donnell and Dave Powers, who, while riding in the motorcade, heard shots come from in front of Kennedy. (ibid, pgs. 293-94) What journalist was in that kind of position in 1964? Even if Bradlee was inclined to accept the official verdict that Oswald acted alone, wouldn’t a true friend of JFK want to make sure the investigation was done properly?

Talbot finally posed the question to Bradlee in 2004. Bradlee was 83 and had been kicked way upstairs at the Post but still had a small office. The answer Bradlee gave Talbot for not lifting a finger to inquire into his friend’s assassination was this: He was worried that if he devoted resources to the case, it would harm him and the Post by allowing people to revive allegations about his overly close personal relationship with Kennedy. (ibid, p. 393)

Talbot left it at that but shouldn’t have. In 1964, when the Warren Commission was ostensibly investigating the murder of President Kennedy, Bradlee was already financially comfortable, having been given sizeable stock options in the Washington Post Company that he knew would make him millions of dollars.

But let us grant Bradlee his (weak) argument. If I were Talbot, after listening to it, I would have immediately replied, “Okay, Ben. That was in 1964. But in 1976, you were at the pinnacle of your career. You had attained the title of executive editor of the Post. Why didn’t you do anything while the House Select Committee on Assassinations was reopening your friend’s murder case?”

Undercutting an Inquiry

Actually, Bradlee did do some things, but they weren’t in support of a thorough reexamination. Author Anthony Summers had called Bradlee and given him a tip about what investigator Gaeton Fonzi had discovered that Cuban exile leader Antonio Veciana had seen Oswald meeting with CIA officer David Phillips at the Southland building in Dallas in late summer 1963. Summers recommended that Bradlee inquire into that incident.

Bradlee put a British intern, David Leigh, on the case; with the proviso that he try and discredit it. Leigh investigated and told Bradlee that he couldn’t discredit it, since it appeared to be true. What Summers and Leigh did not know about Bradlee’s motivation was this: Phillips had also called Bradlee about the Veciana lead and the CIA friendly executive editor wanted to spike the story. (James DiEugenio, Destiny Betrayed, pgs. 363-64)

One of the Post’s writers assigned to report on the House Select Committee was the CIA’s good friend Walter Pincus, who disparaged the committee as “perhaps the worst example of Congressional inquiry run amok.”

But there was one other incident that crystallized Bradlee’s disturbing lack of concern about the mystery surrounding JFK’s murder. In the mid-1970s, the interest in the Kennedy case ratcheted up to an almost fever pitch because of the revelations of the Church Committee about the crimes of the CIA and the FBI and the first televised screening of the Zapruder film showing Kennedy’s head being knocked backwards by the fatal shot, suggesting a shooter in front. Those two events stirred public suspicions and led to the formation of the HSCA.

Many young people were attracted to the case. Two of them, Carl Oglesby and Harvey Yazijian, set up the Assassination Information Bureau to inform the public about new developments in the congressional inquiry. In Boston — where Yazijian lived and where Bradlee was born — the two men faced off in a debate about the case being reopened.

I interviewed Yazijian about this debate for this article. He said, “Jim, to label my encounter with Bradlee a debate is to mischaracterize it.” Yazijian had come prepared to review the evidence in the case and explain why knowledgeable people held the Warren Commission in such low esteem. Instantly, he realized that Bradlee had a different agenda.

“He was vitriolic. He went ballistic right out of the gate. He dismissed all the critics as being irresponsible nutcases. It was nonstop pure vitriol.”

Yazijian tried to present himself as cool and composed, but he was taken aback at how hostile Bradlee was. Yazijian said Bradlee was trying to dismiss all the critics as being an “irresponsible ilk who should not be listened to. He was right; we were wrong.”

It was clear to Yazijian that Bradlee and the Post were invested in the official story and Bradlee did not want to hear any rational argument showing that he might be wrong. He wanted to dismiss all the contrary evidence out of hand via character assassination, thereby eliminating any argument attached to it. Looking back, Yazijian wishes he had been more prepared for this line of attack and had called Bradlee out on it.

In other words, Bradlee ended up constructing a rather perverse legacy around his friendship with his neighbor, the senator-who-became-president. From the above record, one can say that Bradlee was one of the first journalists to combine disdain for JFK’s accomplishments with disinterest in the legitimate questions surrounding his death, even when there was broad public interest in a thorough inquiry into Kennedy’s murder.

Reflecting Bradlee’s curious coolness toward JFK’s death, he concludes his book, Conversations with Kennedy, with a recollection about an invitation from Jackie Kennedy to JFK’s Irish wake at the White House:

“There is much to be said for the wake. Led by Dave Powers, this one was more often than not surprisingly cheerful, and always warm and tender.”

Recall the devastating impact that the murderous weekend in Dallas had just inflicted on the American people and the world. Yet, Bradlee’s takeaway from those horrific events was that he enjoyed a good wake.

The Watergate Reprieve

But Bradlee’s defenders respond to any criticism of the Post’s legendary editor by pointing to Watergate. You can’t deny that was a journalistic triumph of the first order, they say. And it is true that The Washington Post, more than any other media outlet, was responsible for driving Richard Nixon from office because of his abuses of power.

But the problem is that the Post’s version of Watergate has not held up well through history with major elements of the scandal, including how and why it started, having been missed or messed up by Bradlee’s investigative team. Some of that revisionism has originated at Consortiumnews.com due to the work of journalist Robert Parry.

For instance, the Post’s version of Watergate attributes the creation of the Plumbers units to the publication of the Pentagon Papers, but that was not entirely accurate. Based on newly released tapes and documents, it now appears that the creation of the Plumbers and Nixon’s desire to firebomb the Brookings Institution were due to his obsession with Lyndon Johnson’s file on what’s known as the Anna Chennault affair, Nixon’s attempt as a candidate in 1968 to sabotage Johnson’s efforts to negotiate peace in Vietnam. [See Consortiumnews.com’s “The Heinous Crime Behind Watergate.”]

Nixon’s sabotage of those peace talks was successful and helped Nixon prevent a fast-closing Hubert Humphrey from edging ahead to again deny Nixon the White House. In other words, Nixon illegally and treacherously undercut Johnson’s diplomacy to win the presidency. There is not one sentence about this disgraceful episode in the 336 pages of All the President’s Men.

Another astonishing lacuna in that best-selling book is this: there is not any mention of the name Spencer Oliver. Yet, Oliver’s was one of the two phones that burglar James McCord wired for sound during the first Watergate break-in in late May 1972. (The other one was Democratic National Committee chair Larry O’Brien’s, but that bug didn’t work, meaning that Oliver’s phone was the only one that Nixon’s team spied on.)

For decades, no one could come up with a plausible explanation of why this was done or what the burglars heard on the wiretap. But Parry interviewed Oliver at length and learned that Oliver, who was the chair of the Democratic state committees, was running a last-minute effort to derail Sen. George McGovern’s campaign because of doubts that McGovern could win.

In other words, Nixon’s team was hearing the Democratic Party’s most precise delegate count and learning of the last-ditch strategy by Democratic regulars to stop McGovern in favor of someone with a better chance to beat Nixon in November.

That meant the Republicans could turn to conservative Democrats in Texas, where ex-Gov. John Connolly, a Democrat-for-Nixon, still held great sway, to ensure that McGovern got enough delegates at Texas’ June convention to put him in position to win the nomination and then go down to a landslide defeat to Nixon. [See Robert Parry’s Secrecy & Privilege.]

Because the Post’s coverage, led by Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, more or less ignored Oliver and the first break-in focusing instead on the second foiled break-in of June 17, 1972, and the subsequent cover-up these two earlier elements of the story (why was Nixon so frightened about what the Democrats might have on him and what did Nixon get from the bug on Oliver’s phone) were bypassed.

Another interesting fact, relevant to how important Spencer Oliver and his information were to the Watergate scheme, was that the burglars seemed to have gone to great lengths to secure a key to Oliver’s desk. Burglar Eugenio Martinez was trying to hide this key when one of the arresting officers took it from him on June 17. (Jim Hougan, Secret Agenda, pgs. 178-79)

Between the two break-ins when Nixon’s team was only getting information off Oliver’s phone James McCord, one of the team’s leaders, sent his hand-picked assistant, Alfred Baldwin, on an undercover mission to approach Oliver’s secretary Ida Wells, though the precise purpose of the visit has never been made clear. (ibid, p. 202)

But the Post, in its two years of Watergate coverage, never appeared to have made any attempt to tie down these fascinating and important loose ends which raised grave questions about the integrity of the U.S. electoral process in 1968 as well as 1972.

Deep Throat’s Mystery

As for the rest of the mainstream media, its later obsession with Watergate focused only on the identity of the Post’s key source, Deep Throat, who finally revealed himself in 2005 as FBI Associate Director Mark Felt.

Throughout All the President’s Men, there is a rather obvious subtext criticizing the FBI’s investigation of Watergate. Woodward and Bernstein could get away with this in 1974 because the identity of Deep Throat was kept hidden until Felt stepped out of the shadows some three decades later.

During the early months of the Watergate investigation, Felt was the number two man at the FBI, leaving a paradox in the book: If the FBI was conducting a poor investigation, how was Felt able to give Bob Woodward all this interesting information? Today, that question holds two answers:

First, the FBI inquiry was not substandard at all. Neither was the inquiry compromised at the top, which is another accusation the two reporters make. The Bureau’s Watergate investigation, in sharp contrast to its JFK inquiry, was solid, intelligent and thorough.

But because the Post had disguised who Deep Throat was, this allowed Felt to indulge his own private agenda by using Woodward, which is what Bradlee said he feared most. In a private lunch with Woodward, Bradlee asked to know Deep Throat’s position, since he wanted to be sure he had no axe to grind, using the Post to advance a personal vendetta. According to Woodward, he assured Bradlee that this was not the case. (All the President’s Men, p. 146)

However, after Felt revealed himself as Deep Throat and the identity was confirmed by Woodward, Watergate aficionados noted that Felt indeed did have an agenda, fulfilling his lifelong dream of becoming FBI Director. In that sense, Felt’s axe had a two-edged blade.

For one, by leaking this information, Felt was sabotaging Nixon’s acting FBI Director L. Patrick Gray. But Felt could accomplish this only by giving Woodward some good information so he would continue to meet with him. This is why, today, the picture of Deep Throat as drawn by Woodward and Bernstein is slightly humorous. They depict him as a hero who did what he did because he abhorred the “switchblade mentality” of the Nixon White House when he was busy stabbing his boss in the back. (ibid, p. 130)

The risk Woodward ran in this regard was epitomized in the pages of All the President’s Men, allowing Felt to completely fabricate a scene. Felt said President Nixon met with Gray in February 1973 about his appointment as permanent FBI director, with Gray telling Nixon that he had done his job by containing the FBI’s investigation and implicitly threatening Nixon if the appointment were not forthcoming.

Upon hearing this story from Deep Throat, Woodward concludes that Gray had blackmailed Nixon. “I never said that,” Deep Throat laughed. (ibid, p. 270)

This fiction has now been smashed by the declassified tapes and memoranda of the Nixon-Gray meeting. Gray did not lead the meeting at all and did not know what the meeting was about beforehand. In fact, he thought he was going to be replaced. Further, Nixon did almost all the talking. (In Nixon’s Web by L. Patrick and Ed Gray, pgs. 154-81)

Apparently, Woodward never asked Felt how he knew what was discussed since the only people in the room were Gray, Nixon and his domestic adviser John Ehrlichman. But Felt is also the man who twice told Gray that he was not leaking information to any reporters about Watergate. So this kind of duplicity was more or less standard for Woodward’s source.

Secondly, as Ed Gray describes in his memoir, Woodward appears to have attributed other source information to Deep Throat that could not have come from Felt. (Gray, pgs. 294-300)

Though there are always shortcomings in reporting on a complex and developing story like Watergate, the Post’s legendary coverage in retrospect suggests that the reporting was largely superficial and misguided.

The focus was kept on Nixon and his “men,” rather than on the broader corruption of the Washington political system. Once the corrupt group was cleaned out, the wound could heal without any deeper examination of what was wrong. To this day, the Post has shown no interest in exploring the documents about Nixon sabotaging Johnson’s Vietnam peace talks or how those revelations rewrite the history of the Watergate scandal.

Behind the Curve

In Bradlee’s later years as executive editor, the Post trailed miserably on the biggest scandal of Ronald Reagan’s presidency, the Iran-Contra Affair. When Robert Parry, who broke some of the early Iran-Contra stories for The Associated Press, was hired by Newsweek in early 1987, he found an institutional resistance within the Post-Newsweek company against pushing too hard on the scandal.

Parry said he heard concerns from Newsweek executives that taking the story too far might not be “good for the country” and that “we don’t want another Watergate,” i.e., a scandal forcing a second Republican president from office.

Parry recalled that there was particular opposition to digging into evidence that the CIA-backed Nicaraguan Contra rebels were involved in cocaine trafficking, a story that Parry and his AP colleague Brian Barger had pioneered in 1985. After battling his Newsweek editors for three years, Parry left the magazine in 1990.

But the unwillingness to turn over Washington’s many slimy rocks permeated Bradlee’s Washington Post as well. As Jeff Himmelman relates in his biography of Bradlee, the executive editor was planning to step down in 1991 and favored two people to succeed him: Shelby Coffey, a former Post editor who had moved to the Los Angeles Times, and Post managing editor Len Downie. (Himmelman, p. 440)

Bradlee’s job went to Downie with Bradlee becoming the Post’s vice president, a position he held until his death. Coffey became the top editor and vice president of the Los Angeles Times. In 1996-1997, Downie and Coffey, from their editorial perches, oversaw the destruction of San Jose Mercury News reporter Gary Webb’s “Dark Alliance” series, which revived the Contra-cocaine story by showing how the Contra drug smuggling contributed to the crack epidemic and the resulting violence that ravaged U.S. cities and especially African-American communities. The mainstream media attacks on Webb were so savage that he was driven from his profession, into personal despair, and, ultimately, in 2004, to suicide. [See Consortiumnews.com’s “The Sordid Contra-Cocaine Saga.”]

Last fall, when Webb’s story was revived by the movie, “Kill the Messenger,” the New York Times belatedly admitted that the Contras indeed had been involved in cocaine trafficking and that their CIA handlers had looked the other way. But the Post continued bashing Webb and protecting the CIA. [See Consortiumnews.com’s “WPost’s Slimy Assault on Gary Webb.”]

Downie, who had moved on from the Post’s top job to a teaching position at Arizona State University, couldn’t restrain himself from one more pile-on against Webb, circulating by email the Post’s new attack on Webb with the preface: “Gary Webb was no hero, say[s] WP investigations editor Jeff Leen I was at The Washington Post at the time that it investigated Gary Webb’s stories, and Jeff Leen is exactly right. However, he is too kind to a movie that presents a lie as fact.”

In those years, from the 1980s to the present, the Post shifted decisively into a neoconservative ideology, strongly supporting U.S. military interventions and U.S.-backed coups around the world.

For instance, in 2002-03, the Post’s editorial page wrote as flat fact that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction and endorsed the U.S. invasion. Despite the absence of the promised WMD and the ensuing disaster of the war, no senior Post editor was held accountable. The editorial-page editor then, Fred Hiatt, remains the editorial-page editor.

The Shrinking MSM

We all know what happened to the Post and Newsweek in later years. Like many of his MSM colleagues, Bradlee never saw the future coming. As a Post executive and board member, he missed the combination of two factors that directly impacted both of these enterprises: the rise of the Internet and the growing cynicism about the mainstream media.

The combination of those two influences steadily eroded both the magazine and the newspaper. Eventually, they were both sold, Newsweek for one dollar and the Post for $250 million (to Amazon founder Jeff Bezos who paid more than many analysts felt the Post was worth, although the purchase price also included real estate and various other holdings).

In many ways Bradlee exemplified what had gone wrong with the mainstream media, treating the American people as creatures to be herded in some direction desired by the powers-that-be rather than citizens in a democracy who required serious journalism in order to fulfill their responsibilities as voters.

In many ways Bradlee exemplified what had gone wrong with the mainstream media, treating the American people as creatures to be herded in some direction desired by the powers-that-be rather than citizens in a democracy who required serious journalism in order to fulfill their responsibilities as voters.

Parry recalled that during his time at Newsweek, he clashed with editors who thought he didn’t understand the proper role of journalism; Parry thought the goal was to inform the public while Newsweek saw its job as guiding the public.

That was surely true of Bradlee, who was never really interested in giving the people the full truth about the U.S. government and its national security state. As Himmelman pointed out, Bradlee was really more interested in staying on the good side of Katharine Graham, who valued her personal relationships with her peers among the great and powerful.

While Bradlee and Graham might have been willing to oust the scheming climber Richard Nixon, they felt differently about the members of their own elite class such as the well-connected men of the post-World War II CIA and others who ingratiated themselves with skill and grace, whether that was foreign policy guru Henry Kissinger or Hollywood royalty Ronald and Nancy Reagan.

But it was exactly that unspoken snobbishness toward the common American that has generated today’s chasm of distrust between modern news consumers and the mainstream media and the organs of government.

Far from delivering all the important news to his readers, Bradlee sought to restrict the information and control the message. Or as Katharine Graham put it: “There are some things the general public does not need to know and shouldn’t.”

[To read Part One, click here.]

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License