Why have young people in Japan stopped having sex?

What happens to a country when its young people stop having sex? Japan is finding out… Abigail Haworth investigates

Abigail Haworth, Guardian

Abigail Haworth, Guardian-

- The Observer, Saturday 19 October 2013

Ai Aoyama is a sex and relationship counsellor who works out of her narrow three-storey home on a Tokyo back street. Her first name means “love” in Japanese, and is a keepsake from her earlier days as a professional dominatrix. Back then, about 15 years ago, she was Queen Ai, or Queen Love, and she did “all the usual things” like tying people up and dripping hot wax on their nipples. Her work today, she says, is far more challenging. Aoyama, 52, is trying to cure what Japan‘s media callssekkusu shinai shokogun, or “celibacy syndrome”.

Japan’s under-40s appear to be losing interest in conventional relationships. Millions aren’t even dating, and increasing numbers can’t be bothered with sex. For their government, “celibacy syndrome” is part of a looming national catastrophe. Japan already has one of the world’s lowest birth rates. Its population of 126 million, which has been shrinking for the past decade, is projected to plunge a further one-third by 2060. Aoyama believes the country is experiencing “a flight from human intimacy” – and it’s partly the government’s fault.

The sign outside her building says “Clinic”. She greets me in yoga pants and fluffy animal slippers, cradling a Pekingese dog whom she introduces as Marilyn Monroe. In her business pamphlet, she offers up the gloriously random confidence that she visited North Korea in the 1990s and squeezed the testicles of a top army general. It doesn’t say whether she was invited there specifically for that purpose, but the message to her clients is clear: she doesn’t judge.

Inside, she takes me upstairs to her “relaxation room” – a bedroom with no furniture except a double futon. “It will be quiet in here,” she says. Aoyama’s first task with most of her clients is encouraging them “to stop apologising for their own physical existence”.

The number of single people has reached a record high. A survey in 2011 found that 61% of unmarried men and 49% of women aged 18-34were not in any kind of romantic relationship, a rise of almost 10% from five years earlier. Another study found that a third of people under 30had never dated at all. (There are no figures for same-sex relationships.) Although there has long been a pragmatic separation of love and sex in Japan – a country mostly free of religious morals – sex fares no better. A survey earlier this year by the Japan Family Planning Association (JFPA) found that 45% of women aged 16-24 “were not interested in or despised sexual contact”. More than a quarter of men felt the same way.

Learning to love: sex counsellor Ai Aoyama, with one of her clients and her dog Marilyn. Photograph: Eric Rechsteiner/Panos PictureMany people who seek her out, says Aoyama, are deeply confused. “Some want a partner, some prefer being single, but few relate to normal love and marriage.” However, the pressure to conform to Japan’s anachronistic family model of salaryman husband and stay-at-home wife remains. “People don’t know where to turn. They’re coming to me because they think that, by wanting something different, there’s something wrong with them.”

Official alarmism doesn’t help. Fewer babies were born here in 2012than any year on record. (This was also the year, as the number of elderly people shoots up, that adult incontinence pants outsold baby nappies in Japan for the first time.) Kunio Kitamura, head of the JFPA, claims the demographic crisis is so serious that Japan “might eventually perish into extinction”.

Japan’s under-40s won’t go forth and multiply out of duty, as postwar generations did. The country is undergoing major social transition after 20 years of economic stagnation. It is also battling against the effects on its already nuclear-destruction-scarred psyche of 2011’s earthquake, tsunami and radioactive meltdown. There is no going back. “Both men and women say to me they don’t see the point of love. They don’t believe it can lead anywhere,” says Aoyama. “Relationships have become too hard.”

Marriage has become a minefield of unattractive choices. Japanese men have become less career-driven, and less solvent, as lifetime job security has waned. Japanese women have become more independent and ambitious. Yet conservative attitudes in the home and workplace persist. Japan’s punishing corporate world makes it almost impossible for women to combine a career and family, while children are unaffordable unless both parents work. Cohabiting or unmarried parenthood is still unusual, dogged by bureaucratic disapproval.

Aoyama says the sexes, especially in Japan’s giant cities, are “spiralling away from each other”. Lacking long-term shared goals, many are turning to what she terms “Pot Noodle love” – easy or instant gratification, in the form of casual sex, short-term trysts and the usual technological suspects: online porn, virtual-reality “girlfriends”, anime cartoons. Or else they’re opting out altogether and replacing love and sex with other urban pastimes.

Some of Aoyama’s clients are among the small minority who have taken social withdrawal to a pathological extreme. They are recoveringhikikomori (“shut-ins” or recluses) taking the first steps to rejoining the outside world, otaku (geeks), and long-term parasaito shingurus(parasite singles) who have reached their mid-30s without managing to move out of home. (Of the estimated 13 million unmarried people in Japan who currently live with their parents, around three million are over the age of 35.) “A few people can’t relate to the opposite sex physically or in any other way. They flinch if I touch them,” she says. “Most are men, but I’m starting to see more women.”

No sex in the city: (from left) friends Emi Kuwahata, 23, and Eri Asada, 22, shopping in Tokyo. Photograph: Eric Rechsteiner/Panos Pictures

No sex in the city: (from left) friends Emi Kuwahata, 23, and Eri Asada, 22, shopping in Tokyo. Photograph: Eric Rechsteiner/Panos Pictures

Aoyama cites one man in his early 30s, a virgin, who can’t get sexually aroused unless he watches female robots on a game similar to Power Rangers. “I use therapies, such as yoga and hypnosis, to relax him and help him to understand the way that real human bodies work.” Sometimes, for an extra fee, she gets naked with her male clients – “strictly no intercourse” – to physically guide them around the female form. Keen to see her nation thrive, she likens her role in these cases to that of the Edo period courtesans, or oiran, who used to initiate samurai sons into the art of erotic pleasure.

Aversion to marriage and intimacy in modern life is not unique to Japan. Nor is growing preoccupation with digital technology. But what endless Japanese committees have failed to grasp when they stew over the country’s procreation-shy youth is that, thanks to official shortsightedness, the decision to stay single often makes perfect sense. This is true for both sexes, but it’s especially true for women. “Marriage is a woman’s grave,” goes an old Japanese saying that refers to wives being ignored in favour of mistresses. For Japanese women today, marriage is the grave of their hard-won careers.

I meet Eri Tomita, 32, over Saturday morning coffee in the smart Tokyo district of Ebisu. Tomita has a job she loves in the human resources department of a French-owned bank. A fluent French speaker with two university degrees, she avoids romantic attachments so she can focus on work. “A boyfriend proposed to me three years ago. I turned him down when I realised I cared more about my job. After that, I lost interest in dating. It became awkward when the question of the future came up.”

Tomita says a woman’s chances of promotion in Japan stop dead as soon as she marries. “The bosses assume you will get pregnant.” Once a woman does have a child, she adds, the long, inflexible hours become unmanageable. “You have to resign. You end up being a housewife with no independent income. It’s not an option for women like me.”

Around 70% of Japanese women leave their jobs after their first child. The World Economic Forum consistently ranks Japan as one of the world’s worst nations for gender equality at work. Social attitudes don’t help. Married working women are sometimes demonised as oniyome, or “devil wives”. In a telling Japanese ballet production of Bizet’s Carmen a few years ago, Carmen was portrayed as a career woman who stole company secrets to get ahead and then framed her lowly security-guard lover José. Her end was not pretty.

Prime minister Shinzo Abe recently trumpeted long-overdue plans to increase female economic participation by improving conditions and daycare, but Tomita says things would have to improve “dramatically” to compel her to become a working wife and mother. “I have a great life. I go out with my girl friends – career women like me – to French and Italian restaurants. I buy stylish clothes and go on nice holidays. I love my independence.”

Tomita sometimes has one-night stands with men she meets in bars, but she says sex is not a priority, either. “I often get asked out by married men in the office who want an affair. They assume I’m desperate because I’m single.” She grimaces, then shrugs. “Mendokusai.”

Mendokusai translates loosely as “Too troublesome” or “I can’t be bothered”. It’s the word I hear both sexes use most often when they talk about their relationship phobia. Romantic commitment seems to represent burden and drudgery, from the exorbitant costs of buying property in Japan to the uncertain expectations of a spouse and in-laws. And the centuries-old belief that the purpose of marriage is to produce children endures. Japan’s Institute of Population and Social Securityreports an astonishing 90% of young women believe that staying single is “preferable to what they imagine marriage to be like”.

‘I often get asked out by married men in the office who want an affair as I am single. But I can’t be bothered’: Eri Tomita, 32. Photograph: Eric Rechsteiner/Panos PicturesThe sense of crushing obligation affects men just as much. Satoru Kishino, 31, belongs to a large tribe of men under 40 who are engaging in a kind of passive rebellion against traditional Japanese masculinity. Amid the recession and unsteady wages, men like Kishino feel that the pressure on them to be breadwinning economic warriors for a wife and family is unrealistic. They are rejecting the pursuit of both career and romantic success.

‘I often get asked out by married men in the office who want an affair as I am single. But I can’t be bothered’: Eri Tomita, 32. Photograph: Eric Rechsteiner/Panos PicturesThe sense of crushing obligation affects men just as much. Satoru Kishino, 31, belongs to a large tribe of men under 40 who are engaging in a kind of passive rebellion against traditional Japanese masculinity. Amid the recession and unsteady wages, men like Kishino feel that the pressure on them to be breadwinning economic warriors for a wife and family is unrealistic. They are rejecting the pursuit of both career and romantic success.

“It’s too troublesome,” says Kishino, when I ask why he’s not interested in having a girlfriend. “I don’t earn a huge salary to go on dates and I don’t want the responsibility of a woman hoping it might lead to marriage.” Japan’s media, which has a name for every social kink, refers to men like Kishino as “herbivores” or soshoku danshi (literally, “grass-eating men”). Kishino says he doesn’t mind the label because it’s become so commonplace. He defines it as “a heterosexual man for whom relationships and sex are unimportant”.

The phenomenon emerged a few years ago with the airing of a Japanese manga-turned-TV show. The lead character in Otomen (“Girly Men”) was a tall martial arts champion, the king of tough-guy cool. Secretly, he loved baking cakes, collecting “pink sparkly things” and knitting clothes for his stuffed animals. To the tooth-sucking horror of Japan’s corporate elders, the show struck a powerful chord with the generation they spawned.

‘I find women attractive but I’ve learned to live without sex. Emotional entanglements are too complicated’: Satoru Kishino, 31. Photograph: Eric Rechsteiner/Panos PicturesKishino, who works at a fashion accessories company as a designer and manager, doesn’t knit. But he does like cooking and cycling, and platonic friendships. “I find some of my female friends attractive but I’ve learned to live without sex. Emotional entanglements are too complicated,” he says. “I can’t be bothered.”

‘I find women attractive but I’ve learned to live without sex. Emotional entanglements are too complicated’: Satoru Kishino, 31. Photograph: Eric Rechsteiner/Panos PicturesKishino, who works at a fashion accessories company as a designer and manager, doesn’t knit. But he does like cooking and cycling, and platonic friendships. “I find some of my female friends attractive but I’ve learned to live without sex. Emotional entanglements are too complicated,” he says. “I can’t be bothered.”

Romantic apathy aside, Kishino, like Tomita, says he enjoys his active single life. Ironically, the salaryman system that produced such segregated marital roles – wives inside the home, husbands at work for 20 hours a day – also created an ideal environment for solo living. Japan’s cities are full of conveniences made for one, from stand-up noodle bars to capsule hotels to the ubiquitous konbini (convenience stores), with their shelves of individually wrapped rice balls and disposable underwear. These things originally evolved for salarymen on the go, but there are now female-only cafés, hotel floors and even the odd apartment block. And Japan’s cities are extraordinarily crime-free.

Some experts believe the flight from marriage is not merely a rejection of outdated norms and gender roles. It could be a long-term state of affairs. “Remaining single was once the ultimate personal failure,” saysTomomi Yamaguchi, a Japanese-born assistant professor of anthropology at Montana State University in America. “But more people are finding they prefer it.” Being single by choice is becoming, she believes, “a new reality”.

Is Japan providing a glimpse of all our futures? Many of the shifts there are occurring in other advanced nations, too. Across urban Asia, Europe and America, people are marrying later or not at all, birth rates are falling, single-occupant households are on the rise and, in countries where economic recession is worst, young people are living at home. But demographer Nicholas Eberstadt argues that a distinctive set of factors is accelerating these trends in Japan. These factors include the lack of a religious authority that ordains marriage and family, the country’s precarious earthquake-prone ecology that engenders feelings of futility, and the high cost of living and raising children.

“Gradually but relentlessly, Japan is evolving into a type of society whose contours and workings have only been contemplated in science fiction,” Eberstadt wrote last year. With a vast army of older people and an ever-dwindling younger generation, Japan may become a “pioneer people” where individuals who never marry exist in significant numbers, he said.

Japan’s 20-somethings are the age group to watch. Most are still too young to have concrete future plans, but projections for them are already laid out. According to the government’s population institute, women in their early 20s today have a one-in-four chance of never marrying. Their chances of remaining childless are even higher: almost 40%.

They don’t seem concerned. Emi Kuwahata, 23, and her friend, Eri Asada, 22, meet me in the shopping district of Shibuya. The café they choose is beneath an art gallery near the train station, wedged in an alley between pachinko pinball parlours and adult video shops. Kuwahata, a fashion graduate, is in a casual relationship with a man 13 years her senior. “We meet once a week to go clubbing,” she says. “I don’t have time for a regular boyfriend. I’m trying to become a fashion designer.” Asada, who studied economics, has no interest in love. “I gave up dating three years ago. I don’t miss boyfriends or sex. I don’t even like holding hands.”

Asada insists nothing happened to put her off physical contact. She just doesn’t want a relationship and casual sex is not a good option, she says, because “girls can’t have flings without being judged”. Although Japan is sexually permissive, the current fantasy ideal for women under 25 is impossibly cute and virginal. Double standards abound.

In the Japan Family Planning Association’s 2013 study on sex among young people, there was far more data on men than women. I asked the association’s head, Kunio Kitamura, why. “Sexual drive comes from males,” said the man who advises the government. “Females do not experience the same levels of desire.”

Over iced tea served by skinny-jeaned boys with meticulously tousled hair, Asada and Kuwahata say they share the usual singleton passions of clothes, music and shopping, and have hectic social lives. But, smart phones in hand, they also admit they spend far more time communicating with their friends via online social networks than seeing them in the flesh. Asada adds she’s spent “the past two years” obsessed with a virtual game that lets her act as a manager of a sweet shop.

Japanese-American author Roland Kelts, who writes about Japan’s youth, says it’s inevitable that the future of Japanese relationships will be largely technology driven. “Japan has developed incredibly sophisticated virtual worlds and online communication systems. Its smart phone apps are the world’s most imaginative.” Kelts says the need to escape into private, virtual worlds in Japan stems from the fact that it’s an overcrowded nation with limited physical space. But he also believes the rest of the world is not far behind.

Getting back to basics, former dominatrix Ai Aoyama – Queen Love – is determined to educate her clients on the value of “skin-to-skin, heart-to-heart” intimacy. She accepts that technology will shape the future, but says society must ensure it doesn’t take over. “It’s not healthy that people are becoming so physically disconnected from each other,” she says. “Sex with another person is a human need that produces feel-good hormones and helps people to function better in their daily lives.”

Aoyama says she sees daily that people crave human warmth, even if they don’t want the hassle of marriage or a long-term relationship. She berates the government for “making it hard for single people to live however they want” and for “whipping up fear about the falling birth rate”. Whipping up fear in people, she says, doesn’t help anyone. And that’s from a woman who knows a bit about whipping.

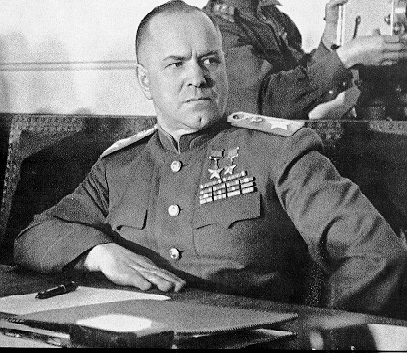

Zhukov is one of the 20th century’s great commanders. The Russians gave him the same title the Mongols gave Subotai and the Greeks gave Alexander: “the one who never lost a battle.” Weird, but I never heard much about him growing up. I knew who he was, of course, but those Cold-War books were a little stingy handing out praise to Soviet generals. Me, I’m not political. I celebrate Zhukov for what he was, a genius at combined-arms attacks. He reminds me of Alexander more than anybody else, and you can’t get higher praise than that. Too bad he was serving Stalin, sure, just like it’s too bad that magnificent Wehrmacht was serving Hitler. But I still salute the Wehrmacht and I still salute Zhukov. Hey, getting yourself a war to command is even tougher than getting a movie to direct, takes even more capital and cooperation from all kinds of prima donnas. A general’s got to go where the work is, and one thing you can say for those 1930s wacko dictators, they gave the generals plenty of chances to showcase their skill sets.

Zhukov is one of the 20th century’s great commanders. The Russians gave him the same title the Mongols gave Subotai and the Greeks gave Alexander: “the one who never lost a battle.” Weird, but I never heard much about him growing up. I knew who he was, of course, but those Cold-War books were a little stingy handing out praise to Soviet generals. Me, I’m not political. I celebrate Zhukov for what he was, a genius at combined-arms attacks. He reminds me of Alexander more than anybody else, and you can’t get higher praise than that. Too bad he was serving Stalin, sure, just like it’s too bad that magnificent Wehrmacht was serving Hitler. But I still salute the Wehrmacht and I still salute Zhukov. Hey, getting yourself a war to command is even tougher than getting a movie to direct, takes even more capital and cooperation from all kinds of prima donnas. A general’s got to go where the work is, and one thing you can say for those 1930s wacko dictators, they gave the generals plenty of chances to showcase their skill sets.

The whole western border, butting up against Mongolia, was left all but undefended. To attack from that direction you’d have to cross the Gobi Desert, which the Japanese considered impossible, then go over the Khingan Mountains, which hit about 5500 feet and are what BLM would proudly call a “roadless area.”

The whole western border, butting up against Mongolia, was left all but undefended. To attack from that direction you’d have to cross the Gobi Desert, which the Japanese considered impossible, then go over the Khingan Mountains, which hit about 5500 feet and are what BLM would proudly call a “roadless area.”