And then all of a sudden, you go from the dashing light-armor knights of the Iraqi plain to the biggest, most vulnerable targets imaginable—thin-skinned vehicles crawling over a completely flat, treeless plain while the drones buzz overhead, armed with Hellfire missiles, just waiting for authorization from a desk jockey in suburban Virginia before they release a weapon designed to destroy much bigger, tougher, Soviet tanks. Suddenly, you, with your Sunni Lawrence of Arabia war-tourist dreams, are nothing but a bug getting zapped by an automated pest-control device.

.

It’s insulting. And the kind of young men who join IS are romantics, of a sort. They might not mind dying in the abstract—most guys don’t, at that age, until they find out what it feels like to get shot in the stomach—but they hate the idea of dying in such an unchivalrous way.

.

So, they take their revenge the best way they can: With a video camera, a hostage, and a short, sharp knife. Why a short knife, by the way? Why not use an ax, if you’re going to behead someone? Because with a short knife, you have to saw the head off slowly. It’s how you kill a sheep. It’s degrading to the victim.

.

Beheading, done with a sharp, heavy ax or sword, was traditionally an aristocratic death in Europe; when Dr. Louis invented the guillotine, he was extending human dignity, as he saw it, by making a noble and quick death by decapitation available to the masses—a huge improvement on hanging, which was usually the “yank on a rope til he stops moving” kind, not the advanced calculation of the Victorian hangman you see in movies. The Parisians loved the new machine; they had a sweet little name for death by guillotine: “Putting your head on the windowsill.” And it was that easy—lay your head down and off it rolled!

.

But decapitation by knife is a very different matter from the sharp, heavy, greased blade of a guillotine. When you saw the head off with a small knife, you’re not trying to make it quick or easy. You’re doing several things at once, aimed at several different audiences who’ll watch the video online: For the audience of IS supporters worldwide, you’re offering revenge porn, revenge for all the airstrikes hitting IS positions over the past few weeks, and for all the other American attacks over the years, inflicted on the body of this American captive.

Suddenly, you, with your Sunni Lawrence of Arabia war-tourist dreams, are nothing but a bug getting zapped by an automated pest-control device.

For the American/Western audience, you’re hoping to provoke disgust and horror intense enough to weaken support for any more intervention in Iraq. Finally, you’re hoping that some Kurdish and Shia Iraqi fighters will see or hear about the video, because you want them terrified of you. It was that terror that led many Iraqi Army units to bug out before they ever even saw the black flag of IS up close. As Brando intoned while the sweat dripped from his fat face in Apocalypse Now, “Terror is your friend…” When you’re a relatively small conventional fighting force like IS, terror is your best weapon.

.

So these videos are eminently practical and effective. The one thing they won’t bring about is the demand the beheader makes: Getting the US to stop the air/drone strikes on IS.

.

But why the emphasis on beheading? IS has used Kalashnikovs to kill low-value prisoners—Syrian and Iraqi soldiers and security men, suspected informers, collaborators—very quickly and efficiently.

.

Automatic rifle fire is the best way to kill lots of people quickly, but it lacks the slow, atavistic drama of beheading—which is why IS uses the knife on its high-value prisoners, especially Americans.

.

Sunni jihadism is a profoundly conservative, defensive movement, a reaction against the corrosive flood of new social rules—above all, uppity women, secularization, and the privileging of civilians over warriors.

.

Sunni jihadis like the men of IS are very willing to use the latest social technology in their propaganda, but that propaganda is in the service of a deeply nostalgic struggle. So naturally, they are drawn to the most universal, powerful, familiar image in war propaganda, all through human history and across all known cultures: The severed head of an enemy.

.

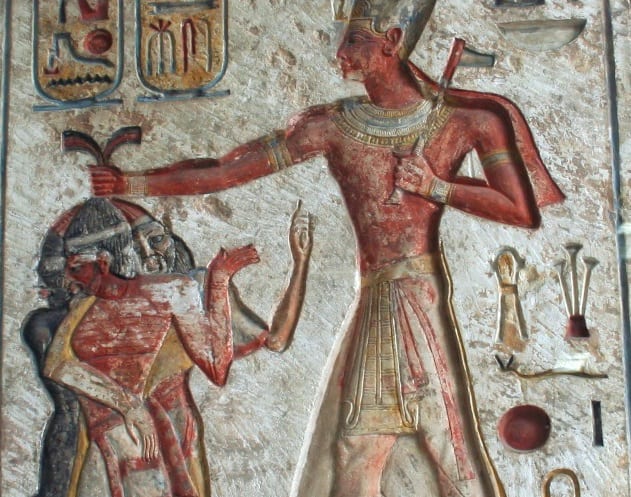

I doubt that the IS crew who put together these videos know much about Mesopotamian history (in fact, IS is downright hostile to history, smashing every artifact they can find)—but the fact is, there are Assyrian bas-reliefs showing the very same scene, acted out on pretty much the same patch of ground, almost 3000 years ago. Using the best visual-media technology available at the time—stone walls carved in bas-relief—Assyrian sculptors created in loving detail a portrait of their King, Sennerachib, using a short knife to saw off the head of a kneeling prisoner. All that’s missing is a link to Facebook and that Guantanamo jumpsuit.

.

The Assyrians were experts in using the available media to spread terror, or respect—the distinction wasn’t so clear in their world—for their war-making ability. They used the same skill in carving bas-reliefs to show their kings blinding prisoners, impaling rebels, and otherwise displaying their familiarity with the pain centers of the human body. But those are all exotic variants; always and everywhere, the most basic form of showing your victory over a prisoner and his tribe is decapitation.

.

Decapitation is the classic way of demonstrating that you have defeated your rival, once and for all. Some cultures found it more practical to take less bulky, messy trophies than the whole head, like scalps or ears. The Tibetans—who have never been anything like the sweet pacifists Hollywood Buddhists imagine them to be—named a region of their country “The Plain of Stinking Ears” because, after a victory over the Mongols, they moved among the enemy dead collecting ears, so many they filled several carts, and then laid the ears out on the ground to dry.

.

…The ten myriarchies of Tibetan troops defeated the many hundreds of thousands of Stod Hor troops. As proof of having killed many thousand [Mongols], they cut off only the right ears [of the dead] and put them into many donkey loads… the ears started stinking. After they had exposed them to the sun on a cool plain, the stone enclosure…is today known as ‘stone enclosure of the ears’ (Tib. Rna ba’i lhas).

.

When Tibetans called the place “Plain of Stinking Ears,” they weren’t complaining or deploring the alleged horrors of war. Deploring such things is a very, very recent trend. The Tibetans were bragging, not complaining. The stench of the enemies’ ears was a source of deep patriotic pleasure for them, and a kind of humor as well: “Whoa, we collected so many durn Mongol ears, they stank the place up for good!”

.

Then there were scalps, penises, and other body parts—all ways of confirming the death of an enemy without the trouble of bringing back an entire head.

.

The Mayans, always inventive where human anatomy was concerned, liked to tinker with their prisoners of war by removing their fingernails, and devoted huge, detailed frescoes to showing the unhappy, bound prisoners looking at the blood pouring from their mangled fingers.

.

But the trouble with all this elaborate mangling, as compared to decapitation, is that the victim could survive the operation. When you took the head, that wasn’t a possibility. So, across the centuries, around the globe, the gold standard in war propaganda has always been the removal of an enemy’s head.

.

There’s a practical side to lopping off the head, of course—it’s guaranteed to diminish the combat value of the victim—but its importance as war propaganda is much greater. It’s a show of power—“look what we can do!”—and a deterrent to future challengers (“You want this to happen to you? Then don’t mess with us!”), but it’s also a revenge movie for audiences who aren’t satisfied with fictional representations of revenge, and a demonstration, for the devout, that God is on the side of the decapitator, and has abandoned the decapitate-ee.

.

The first, simplest method of displaying this trophy was to post it—literally, as in ‘stick it on a post’ and put the post up in a prominent position, like a crossroads, the entrance to the chieftan’s hut, or the border zone between two clans’ territories, as a way of saying, “You might want to stay on your side.”

.

But the actual severed head, though a powerful image, had its limitations. It didn’t last, for one thing. So, as communications tech evolved—and I’m talking about the last several thousand years here, not just the last couple of decades—tribes’ ways of disseminating the image of the severed head that would reach a wider audience and last through the hot season without drawing flies.

.

Stone-carving, a huge breakthrough in war propaganda tech, allowed a conqueror to leave a record of his ravages that would, in theory, last forever. Yeah, maybe your Art History class chose to focus on nice images like the bust of Nefertiti or the Pieta, but those were exceptions. As soon as human cultures discovered stone-carving, slaves were put to work carving, in loving detail, all the monstrous tortures and slow, unpleasant deaths inflicted on enemy combatants and prisoners of war.

.

One of the most popular scenes carved in stone, painted on wall murals, etched into panels, and recorded in every known writing system, was the killing of prisoners taken in war. This mass ritual killing was a pre-television way of bringing the gore to the home front, as those unlucky enough to be taken alive would be marched back to the capital and killed, either by the ruler or at the ruler’s command, in front of huge, cheering crowds. The sheer number of depictions of these killings, by cultures all over the world, shows their importance as propaganda. Pharaoh Ramses II, shown four or five times life size, grabs prisoners representing three rival countries—a Syrian, Nubian, and Libyan—by their distinctly styled top-knots, bringing their necks up to a good angle for the ax he’s holding.

.

Japanese troops in China, 1894, watch happily as prisoners are brought up and beheaded, their Manchu ponytails rolling in blood.

.

A British Royal Marine holds up two severed heads, both Chinese-Malaysian villagers suspected of Communist sympathies, in the 1948 CI campaign.

.

You could actually argue that the most basic subject for human art, across all media and all eras, is the depiction of a victorious soldier holding up the severed head of an enemy. It’s a synecdoche for victory, instantly understandable without language, across cultures.

.

So it’s only natural that as communications media change, that same image will be disseminated by the new media. First came the heads-on-sticks, then stone-cutting—decapitations in bas-relief along the palace walls, to impress visitors with the wisdom of obedience. Then, with the printing press, it was possible to show the most important beheadings to people who might never leave their villages to go to the capital.

.

After the near-miss of the Guy Fawkes plot to blow up Parliament in 1605, gloating Protestants found a way to combine old and new by publishing wood-block prints of the severed heads of Fawkes and his fellow Papists, stuck up on pikes like a barber’s advertisement for new beard stylings for hipsters.

.

You might expect, given this long history of exploiting new tech to disseminate the beloved image of the severed head, that when photography, then motion pictures, come into use, we would see more and more detailed images of this scene. But it didn’t quite happen that way. There was a little thing called the Enlightenment, that convinced some human cultures—not all, but disproportionately those which had the money and advanced tech to use film and photo—that we were actually nice guys, and that it was a little barbaric to devote so much artistic energy to heads without bodies.

.

Beheadings still took place, on even larger scale—but they were off-stage now, as the Victorians developed a sly new way to exploit gore. As the colonial empires grew more and more powerful, they no longer needed to show the folks on the home front images of enemies’ severed heads. It went without saying that British, French, and Spanish colonial armies could slaughter hundreds of “natives” without suffering serious casualties, and showing those slaughters in detail might awaken something like pity.

.

So Victorian war propaganda focused on the few, the very few, European casualties of the colonial wars. The “natives” who died at a rate of 100, or even 1000 to one, in some of those late colonial slaughters, were unfilmed, as the empires struggled to make their invasions seem like a grim moral duty rather than a bloody spree.

.

Only the latecomers, the imitators, like Japan—doing its best to act like the big boys of the colonial enterprise—were naïve enough to produce beheading images. They were slow to get the message, and it cost them dearly.

.

What the cutting edge empires, particularly the Anglos, had learned, was that when it comes to beheadings, it is better to receive than to give. Better to let the foolish, old-school warriors try to inspire their troops by making videos of themselves holding up a Westerner’s head. It’s the best propaganda the West could ask, in the run-up to massive air strikes.

.

The high point of this new strategy was the waning British Empire’s brilliant propaganda campaign against the Kikuyu in Kenya during the Mau-Mau Uprising of the 1950s. If you watched English-language media, all the beheading, mutilating, and other low-tech bloodshed was on the hands of the Kikuyu rebels. The Empire was merely trying to restrain their bloody hands. After a few scare movies and hysterical, blood-soaked radio broadcasts, “Mau-Mau” meant sheer terror.

.

Only when Caroline Elkins looked back at the records of the rebellion did the truth come out. The Kikuyu, driven from their lands, revolted with minimal violence, killing only 32 British colonists over the whole war. The Empire killed or maimed 90,000 Kikuyu over the same period, and still came away with the role of peacemaker, restorer of order. (Click here to see this BBC account of the British counterinsurgency campaign.—Ends)

Mau-Mau prisoners. Their treatment was despicable, but the Brits had the upper hand in propaganda power. They still enjoy it, thanks to their close affiliation with the American juggernaut.

.

That’s the way you do it. The good old days of severed-head videos just don’t work like they used to. It’s not that we don’t kill; we kill wonderfully, better than ever. But the tech has gotten too good for us. Now that everyone from Kuala Lumpur to Oslo can watch your knife cutting through the fat on a beheading victim’s neck, the power of the stylized depictions in earlier media is gone. What’s left is more like a surgery demonstration, and it’s out of tune with the happy tone of the social media—Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest—you’re sending it through.

.

What you want on those media is to be an object of sympathy—the decapitated, not the decapitator. Well, “you,” the individual losing his head, may not particularly feel thrilled that you’re serving as excellent passive-aggressive Western propaganda and airstrike pretext. You singular, the unlucky adrenaline freak who thought it’d be a smart idea to go to Iraq, may not be pleased at all. But in the tribal sense, you are doing much more for the propaganda goals of your people—the ones with the drones—than that fool of an Ali-G-hadi with the knife is for his.

.

We’re all familiar and comfortable with the second kind of propaganda, showing the devastation wrought by whatever enemy the propagandist is trying to demonize at the time. But, again, until recently, that kind of pity-based propaganda was a very minor variant on war propaganda that stressed the devastation wrought by our side. When this kind of war propaganda shows images of pain, death, and destruction, it’s a way of reassuring the home folks that we are the biggest badasses around, and they are the ones suffering devastation.

.

It’s funny how many people nod their heads when someone intones Sherman’s pithy phrase about war as Hell, but forget that it’s a Hell that takes a lot of energy, one that has to be sustained by nonstop, enthusiastic human effort. That ought to tell us something most people would rather forget: We have a huge, endlessly-renewed appetite for cruelty, as long as our clan/tribe/sect/nation is the one dishing it out, rather than taking it.

.

In fact, it’s only very recently that human cultures have learned to be coy about that fact. Before the Victorians came up with the brilliant notion of depicting conquest as a dreary but needful chore, war propaganda was an innocent, constant celebration of horrors committed by the victors, incised on the bodies of the losers.

.

This article appears in PandoQuarterly issue three, published later this month.

(Original iteration Sept. 3, 2014)

Gary Brecher is the War Nerd.