Did you sign up yet for our FREE bulletin?

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

ALL CAPTIONS AND PULL QUOTES BY THE EDITORS NOT THE AUTHORS

Please share this article as widely as you can.

In the context of the revolution that erupted in Germany as the country suffered defeat in November 1918, a revolutionary situation also arose in Strasbourg, capital of Alsace, a province that still belonged to the Reich at that time.

Inspired by the proclamation of a “free and socialist republic” in Berlin by Karl Liebknecht on the 9th of that month — and the proclamation, on November 8, of a Bavarian soviet republic (Räterepublik) in Munich, mutinous soldiers as well as civilians seeking radical political and social changes, mostly workers, established a Russian-style revolutionary council or “soviet” in the Alsatian capital and immediately introduced all sorts of radical democratic reforms, including abolition of censorship, wage increases, improved working conditions, the right to strike and to demonstrate, etc.

In addition, the revolutionaries declared that they wanted “nothing to do with the capitalist states” and desired to be neither German nor French but aspired to be able to live, thanks to the “triumph of the red flag,” in a “Republic of Alsace-Lorraine” (Republik Elsaß-Lothringen) that would be free, democratic and linguistically tolerant. A red flag fluttered from the lofty spire of the Alsatian capital, but the democratic project launched there resonated throughout the province: revolutionary movements simultaneously emerged in many other towns of the province, including Colmar, Mulhouse, Haguenau, Molsheim, Neuf-Brisach, Ribeauvillé, Saverne, and Sélestat. Red flags also appeared in the city of Metz, major city of the northern part of Alsace’s neighbouring province, Lorraine, likewise still part of the German Reich in 1918, though not for much longer.

In Strasbourg, the local bourgeoisie, overwhelmingly German-speaking, as well as the local social-democratic leaders, were horrified and decided that they preferred to be “French rather than red.” They appealed to the French army to “rush to Strasbourg as soon as possible” in order to put and end to “red rule” in the city. French troops entered Strasbourg a few days earlier than planned, namely on November 22, overthrew the soviet and cancelled all the democratic measures it had fathered. Strasbourg and the rest of Alsace (and the north of Lorraine) were unilaterally and unceremoniously annexed by France and subjected to a draconian process of “re-francisation”, including a prohibition of the use of the German and even Alsatian languages in education and in the public administration, the demotion of persons of insufficiently French origin to the status of second-class citizens, and the expulsion or ostracism of anyone suspected of disloyalty to France; the famous Doctor Albert Schweitzer was one of the victims of this sort of treatment. After their “liberation”, the Alsatians were less free than before and were no longer allowed to speak their own language, and many of them were (mis)treated as aliens in their own land.

Meeting of the Strasbourg soviet on November 15, 1918 (Bibliothèque nationale et universitaire de Strasbourg 686107, CC BY 2.0, c/o Wikimedia Commons)

The case of Alsace illustrates the sad fact that, contrary to conventional wisdom, the Great War was not a “war for democracy” at all. Even the arguably most democratic of all belligerent powers, France, clearly did not fight for ideals such as democracy, justice, and the Wilsonian principles of self-determination; its victory represented the triumph of a fanatical and intolerant version of nationalism, a consolidation of authoritarian rule, and a setback for democracy.

*

About the author  Jacques R. Pauwels is historian and political scientist, author of ‘The Myth of the Good War: America in the Second World War’ (James Lorimer, Toronto, 2002). His book is published in different languages: in English, Dutch, German, Spanish, Italian and French. Together with personalities like Ramsey Clark, Michael Parenti, William Blum, Robert Weil, Michel Collon, Peter Franssen and many others… he signed “The International Appeal against US-War”. Jacques R. Pauwels is historian and political scientist, author of ‘The Myth of the Good War: America in the Second World War’ (James Lorimer, Toronto, 2002). His book is published in different languages: in English, Dutch, German, Spanish, Italian and French. Together with personalities like Ramsey Clark, Michael Parenti, William Blum, Robert Weil, Michel Collon, Peter Franssen and many others… he signed “The International Appeal against US-War”.

Featured image: Proclamation of the republic in Strasbourg on November 10, 1918 (Bibliothèque nationale et universitaire de Strasbourg 686071, c/o Wikimedia Commons)

The original source of this article is Global Research

[/su_spoiler]

The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of The Greanville Post. However, we do think they are important enough to be transmitted to a wider audience.

All image captions, pull quotes, appendices, etc. by the editors not the authors.

YOU ARE FREE TO REPRODUCE THIS ARTICLE PROVIDED YOU GIVE PROPER CREDIT TO THE GREANVILLE POST VIA A BACK LIVE LINK.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

an>[/su_animate]

Unfortunately, most people take this site for granted.

DONATIONS HAVE ALMOST DRIED UP…

PLEASE send what you can today!

JUST USE THE BUTTON BELOW

[premium_newsticker id=”211406″]

Don’t forget to sign up for our FREE bulletin. Get The Greanville Post in your mailbox every few days.

[newsletter_form]

Please make sure these dispatches reach as many readers as possible. Share with kin, friends and workmates and ask them to do likewise.

Jacques Pauwels Jacques Pauwels

August 19, 1942, 80 Years Ago

Landing craft draw away from transport boat during raid on Dieppe.

Landing craft draw away from main gunboat during Operation Jubilee (Raid on Dieppe)

The tide of World War II turned in early December 1941, when a counter-offensive of the Red Army in front of Moscow signaled the failure of Hitler’s Blitzkrieg strategy. That setback doomed Nazi Germany to lose a war it had to fight without the benefit of Caucasian oil and other resources it had hoped to gain through a speedy victory over the Soviet Union. The war was far from over, however, and for the time being the Red Army continued to do battle with its back to the wall, so to speak. Material help from the United States and Great Britain was forthcoming, but what the Soviets really needed from their allies was effective military assistance. And so Stalin asked Churchill and Roosevelt to open a second front in Western Europe. An Anglo-American landing in France, Belgium, or Holland would have forced the Germans to withdraw troops from the Eastern Front, and would therefore have afforded the Soviets much-needed relief.

In Great Britain and in the USA, which had entered the war only recently, in December 1941, political and military leaders were divided with respect to the possibilities and the merits of a second front. A number of British and American army commanders – including the American chief of staff, George Marshall, as well as General Eisenhower – wanted to land troops in France as soon as possible. They enjoyed the support of President Roosevelt, at least initially. He had promised Churchill that the United States would give priority to the war against Germany, and would settle accounts with Japan later; this decision became known as the “Germany First” principle. Consequently, Roosevelt was eager to deal with Germany right away, and this task required opening a second front. In May 1942 Roosevelt promised the Soviet minister of foreign affairs, Molotov, that the Americans would open a second front before the end of the year.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, on the other hand, was an outspoken opponent of a second front. He may have feared, as some historians suggest, that a landing in France might lead to a duplication of the murderous warfare associated with the battlefields of northern France in the First World War. But it is more likely that Churchill liked the idea that Hitler and Stalin were administering a major bloodletting to each other on the Eastern Front, and that he believed that London and Washington would benefit from a stalemated war in the East. Since he already had nearly three years of war experience, Churchill had much influence on Roosevelt, a newcomer to the war in Europe. It is therefore understandable that the opinion of the British leader ultimately prevailed, and that plans for opening a second front in 1942 were quietly discarded. In any event, Roosevelt himself discovered that this course of action – or rather, inaction – opened up some attractive prospects.

For example, it allowed him, in spite of the “Germany First” principle, to quietly commit a high proportion of manpower and equipment to the war in the Pacific, which was very much “his” war, and where American interests were more directly at stake than in Europe. He and his military and political advisors also started to realize that defeating Germany would require huge sacrifices, which the American people would not be delighted to bring. Landing in France was tantamount to jumping into the ring for a face-off with a formidable German opponent, and, even if ultimately successful, that would be a bloody and costly affair. Was it not far wiser to stay safely on the sidelines, at least for the time being, and let the Soviets slug it out against the Nazis?

With the Red Army providing the cannon fodder needed to vanquish Germany, the Americans and their British allies would be able to minimize their own losses. Better still, they would be able to build up their strength in order to intervene decisively at the right moment, like a deus ex machina, when the Nazi enemy and the Soviet ally would both be exhausted. With Great Britain at its side, the USA would then be able to play the leading role in the camp of the victors, to act as supreme arbiter in the sharing of the spoils of the supposedly common victory, and to create a “new order” of its liking in Europe. In the spring and summer of 1942, with the Nazis and Soviets locked in a titanic battle, watched from a distance by the “Anglo-Saxon” tertius gaudens, it did indeed look as if such a scenario might come to pass. (Incidentally, the hope for a long, drawn-out conflict between Berlin and Moscow was reflected in numerous American newspaper articles and in the much-publicized remark already uttered by Senator Harry S. Truman on June 24, 1941, only two days after the start of the Nazi attack on the Soviet Union: “If we see that Germany is winning, we should help Russia, and if Russia is winning, we should help Germany, so that as many as possible perish on both sides.”)

Of course, the Americans and the British could not reveal the true reasons why they did not wish to open a second front. Instead, they pretended that their combined forces were not yet strong enough for such an undertaking. It was said then – and it is still claimed now – that in 1942 the British and Americans were not yet ready for a major operation in France. Allegedly, the naval war against the German U-boats first had to be won in order to safeguard the required transatlantic troop transports. However, troops had been successfully ferried from North America to Great Britain for quite some time, and in the fall of that same year the Americans would experience no trouble whatsoever landing a sizable force in distant North Africa, on the same side of the admittedly dangerous Atlantic Ocean. (These landings, known as Operation Torch, involving the occupation of French colonies such as Morocco, did not force the Germans to transfer troops from the Eastern Front, did not provide any relief to the Soviets, and can therefore not be construed as the opening of a second front.)

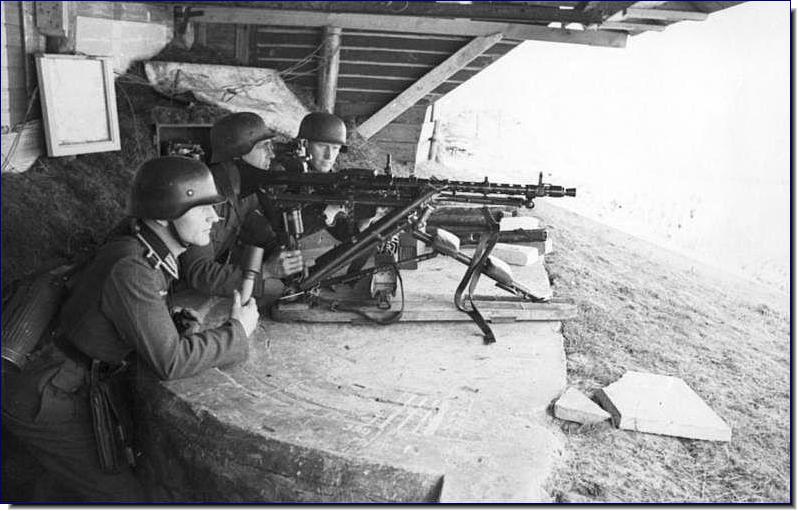

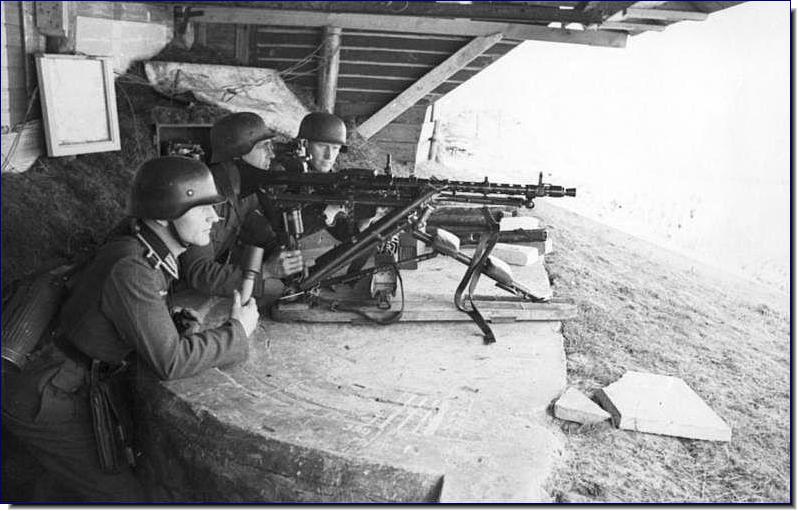

In reality, it was already possible in the summer of 1942 to land a sizable force in France or elsewhere in Western Europe and open a second front. The British army had recuperated from the troubles of 1940, and large numbers of American and Canadian troops had joined them on the British Isles and were ready for action. Furthermore, it was not a secret that the Germans only had relatively few troops available to defend thousands of kilometres of Atlantic coast, and these troops also happened to be of considerably inferior quality compared to their forces on the Eastern Front. On the Atlantic coast, Hitler had about 60 divisions at his disposal, which were generally deemed to be second-rate, while no less than 260 German divisions did battle in the East. It is a fact, furthermore, that on the French coast in 1942 the German troops were not yet as strongly entrenched as they would be later, namely, at the time of the landings in Normandy in June 1944; the order to build the fortifications of the famous Atlantic Wall was only given by Hitler in August 1942, and the construction would drag on from the fall of 1942 until the spring of 1944.

Canadian infantrymen disembark from a landing craft in England during a training exercise before Operation Jubilee, the Raid on Dieppe, France, in August 1942 (MIKAN 3194482) Stalin, who knew that the German defences in Western Europe were weak, continued to press London and Washington for a landing in France. Churchill also experienced considerable domestic pressure in favour of a second front, for example from members of his own cabinet, such as Richard Stafford Cripps, and particularly from the side of the trade unions, whose members were sympathetic to the plight of the Soviets. Thankfully, relief from this relentless pressure came suddenly to the British Prime Minister in the form of a tragedy that appeared to demonstrate conclusively that the Western Allies were not yet able to open a second front: on August 19, 1942, a contingent of Allied soldiers, sent on a mission from England to the French port of Dieppe, seemingly in an effort to open some sort of “second front,” were tragically routed there by the Germans.

The Germans were ready. Dieppe was a strong point in Hitler's Atlantic Wall. Of the total of 6,086 men who made it ashore, 3,623 – almost 60 percent – were either killed, wounded, or captured. The British Army and Navy suffered approximately 800 casualties, and the RAF lost 106 aircraft. The 50 American Rangers who participated in the raid had 3 casualties. But the bulk of the losses were suffered by Canadian troops, with nearly 5,000 men the bulk of the entire force; no less than 3,367 of them – 68 percent! – became casualties; about 900 were killed, nearly 600 were wounded, and the rest were taken prisoner. Of losses such as these, it is traditionally considered that they were “not in vain”; but unsurprisingly, the media and the public wanted to know what the objectives of this raid had been, and what it had achieved, especially in Canada. However, the political and military authorities only provided unconvincing explanations, though these duly found their way into the history books. For example, the raid was presented by Churchill as a “reconnaissance in force,” as a necessary test of the German coastal defences. But did one really have to sacrifice thousands of men to learn that the Germans were strongly entrenched in a seaport surrounded by high cliffs, in other words, in a natural fortress? In any event, crucial information such as the location of pillboxes, cannon, and machine gun positions could have been gleaned through aerial reconnaissance and through the services of local resistance fighters.

Fiasco: Bodies of Canadian soldiers lie among damaged landing craft and Churchill tanks of the Calgary Regiment after Operation Jubilee, August 19, 1942 (MIKAN 3192368)

Talking about the Résistance, the raid was also purported to boost the morale of the French partisans and the French population in general; if so, it was unquestionably counterproductive. Indeed, the outcome of the operation, an ignominious withdrawal from a beach littered with abandoned equipment and corpses, and the sight of exhausted and dejected Canadian soldiers being marched off to a POW camp, was not likely to cheer up the French. If anything, the affair provided grist for the propaganda mill of the Germans, allowing them to ridicule the incompetence of the Allies, boast of their own military prowess, and thus dishearten the French while giving a lift to Germany’s own civilians, who were very much in need of some good news on account of the constant flow of bad tidings from the East.

Last but not least, Operation Jubilee was also claimed to have been an effort to provide some relief to the Soviets. It is obvious, however, that Dieppe was merely a pinprick, unlikely to make any difference whatsoever with respect to the fighting on the Eastern Front. It did not cause the Germans to transfer troops from the East to the West; on the contrary, after Dieppe the Germans could feel reasonably sure that in the near future no second front would be forthcoming, so that they actually felt free to transfer troops from the west to the East, where they were desperately needed. To the Red Army, then, Dieppe brought no relief.

Historians have mostly been happy to regurgitate the official rationalizations of Jubilee, and in some cases they have invented new ones. Just recently, for example, the Dieppe raid was proclaimed to have been planned also, if not primarily, for the purpose of stealing equipment and manuals associated with the Germans’ Enigma code machine, and possibly even all or parts of the machine itself. But would the Germans not immediately have changed their codes if the raid had achieved that objective? (The argument that the plan was to secretly steal the Enigma material, and that that the raiders would have blown up the installations prior to withdrawing from Dieppe, thus destroying evidence of the removal of Enigma equipment, is unconvincing, because it presupposes a high degree of naivety on the part of the Germans.)

After the June 1944 allied landings in Normandy, code-named Operation Overlord, an ostensibly convincing rationale for Operation Jubilee was concocted. The Dieppe Raid was now triumphantly revealed to have been a “general rehearsal” for the successful Normandy landings. Dieppe had supposedly been a test of the German defences in preparation for the big landing yet to come. Lord Mountbatten, the architect of Jubilee, who was – and continues to be – blamed by many for the disaster, thus claimed that “the Battle of Normandy was won on the beaches of Dieppe” and that “for every man who died in Dieppe, at least 10 more must have been spared in Normandy in 1944.” A myth was born: the tragedy of Jubilee had been the sine qua non for the triumph of Overlord.

A very important military lesson had allegedly been learned at Dieppe, namely, that the German coastal defences were particularly strong in and around harbours. It was for this reason, presumably, that the Normandy landings took place on the harbourless stretch of coastline north of Caen, with the Allies bringing along an artificial harbour, code-named Mulberry. But was it not self-evident that the Germans would be more strongly entrenched in seaports than in insignificant little beach resorts? Had it really been necessary to sacrifice thousands of men in order to learn that lesson? And one must also wonder whether information, obtained from a “test” of the German coastal defences in the summer of 1942, was still relevant in 1944, especially since it was mostly in 1943 that the formidable Atlantic Wall fortifications had been built. If Dieppe was a “general rehearsal,” why was the main event not staged until two years later? Is it not absurd to proclaim Jubilee as a rehearsal for an operation that had not even been conceived yet? Finally, the advantage of lessons learned at Dieppe, if any, were almost certainly offset by the fact that at Dieppe the Germans had also learned lessons, and possibly more useful lessons, about how the Allies were likely – and unlikely – to land troops. The idea that the tragedy of Jubilee was a precondition for the triumph of Overlord, then, is merely a useful myth.

Canadian troops march through the city as prisoners, not conquerors.

Even today, then, the Dieppe tragedy remains shrouded in disinformation and propaganda. But perhaps we can catch a glimpse of the truth about Dieppe by finding inspiration in an old philosophical conundrum: If one seeks to fail, and does, does one fail, or succeed? If a military success was sought at Dieppe, the raid was certainly a failure; but if a military failure was sought, the raid was a success. In the latter case, we should inquire about the real objective of the raid, or, to put it in functionalist terms, about its “latent,” or hidden, rather than its “manifest” function.

There are many indications that military failure was intended. First, the town of Dieppe happened to be, and was known to be, an eminently defensible site, and therefore necessarily one of the strongest German positions on the Atlantic coast of France. Anyone arriving there by ferry from England sees immediately that this port, surrounded by high and steep cliffs, bristling at the time with machine guns and cannon, must have been a deadly trap for the attackers. The Germans could not believe their eyes when they found themselves being attacked there. One of their war correspondents, who witnessed the inevitable slaughter, described the raid as “an operation that violated all the rules of military logic and strategy.” Other factors, such as poor planning, inadequate preparations, inferior equipment (such as tanks that could not negotiate the pebbles of Dieppe’s beach), make it seem more likely that the objective was military failure, rather than success.

On the other hand, the Dieppe operation, including its bloody failure, actually made sense if it was ordered for a “latent” non-military purpose. Military operations are frequently carried out to achieve a political objective, and that seems to have been the case at Dieppe in August 1942. The Western Allies’ political leaders in general, the British political leadership in particular, and Prime Minister Churchill, above all, found themselves under relentless pressure to open a second front, were unwilling to open such a front, but lacked a convincing justification for their inaction. The failure of what could be presented as an attempt to open a second front, or at least as a prelude to the opening of a second front, did provide such a justification. Seen in this light, the Dieppe tragedy was indeed a great success, even a double success. First, the operation could be, and was, presented as a selfless and heroic attempt to assist the Soviets. Second, the failure of the operation seemed to demonstrate only too clearly that the western Allies were indeed not yet ready to open a second front. If Jubilee was intended to silence the voices clamouring for the opening of a second front, it was indeed a great success. The Dieppe disaster silenced the popular demand for a second front, and allowed Churchill and Roosevelt to continue to sit on the fence as the Nazis and the Soviets slaughtered each other in the East.

The political motivation for Dieppe would explain why the lambs that were led to the slaughter were not American or British, but Canadian. Indeed, the Canadians constituted the perfect cannon fodder for this enterprise, because their political and military leaders did not belong to the exclusive club of the British-American top command who planned the operation, and who would obviously have been reluctant to sacrifice their own men. Our hypothesis likewise explains why the British were also involved, but in much smaller numbers, and why the Americans sent only a token force.

After the tragedy of Dieppe, even Stalin stopped begging for a second front. The Soviets would eventually get one, but only much later, in 1944, when Stalin was no longer asking for such a favour. At that point, however, the Americans and the British had urgent reasons of their own for landing on the coast of France. Indeed, after the Battles of Stalingrad and Kursk, when Soviet troops were relentlessly grinding their way towards Berlin, “it became imperative for American and English strategy,” as two American historians (Peter N. Carroll and David W. Noble) have written, “to land troops in France and drive into Germany to keep most of that country out of [Soviet] hands.” When a second front was finally opened in Normandy in June 1944, it was not done to assist the Soviets, but to prevent the Soviets from winning the war on their own.

The Soviets finally got their second front when they no longer wanted or needed it. (This does not mean that did they did not welcome the landings in Normandy, or did not benefit from the belated opening of a second front; after all, the Germans remained an extremely tough opponent until the very end.) As for the Canadians, who had been sacrificed at Dieppe, they also got something, namely, heaps of praise from the men at the top of the military and political hierarchy. Churchill himself, for example, solemnly declared that Jubilee had been “the key to the success of the landings in Normandy” and “a Canadian contribution of the greatest significance to final victory.” The Canadians were showered with prestigious awards, including no less than three Victoria Crosses. The hyperbolic kudos and the unusually high number of VCs probably reflected a desire on the part of the authorities to atone for their decision to send so many men on a suicidal mission in order to achieve highly questionable political goals.

Jacques R. Pauwels is a people's historian. In the tradition pioneered by Marx and Engels, and continued by Michael Parenti, Howard Zinn, Eric Hobsbawm, Leo Huberman, and others of similar merit, he writes history that is not only firmly grounded in truth but is aimed at liberating the mind from the claptrap of existing ruling class mythology. Jacques Pauwels is The Greanville Post's resident historian. Jacques R. Pauwels is a people's historian. In the tradition pioneered by Marx and Engels, and continued by Michael Parenti, Howard Zinn, Eric Hobsbawm, Leo Huberman, and others of similar merit, he writes history that is not only firmly grounded in truth but is aimed at liberating the mind from the claptrap of existing ruling class mythology. Jacques Pauwels is The Greanville Post's resident historian.

Prof. Pauwels has taught European history at varous universities in Ontario, Canada, including the University of Waterloo and the University of Guelph. His books include Big Business and Hitler, The Great Class War 1914-1918, and The Myth of the Good War: America in the Second World War, all published byJames Lorimer in Toronto. His new (2022) book, Myths of Modern History, is now also available stateside: https://www.casematepublishers.com/myths-of-modern-history.html . For a recent review of three of his books by Inderjeet Parmar, professor of international politics at the City University of London, see Review: A Trilogy That Challenges the Core Self-Declared Virtues of Western Civilisation.

Print this article

The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of The Greanville Post. However, we do think they are important enough to be transmitted to a wider audience.

Did you sign up yet for our FREE bulletin?

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

ALL CAPTIONS AND PULL QUOTES BY THE EDITORS NOT THE AUTHORS

Read it in your language • Lealo en su idioma • Lisez-le dans votre langue • Lies es in Deiner Sprache • Прочитайте это на вашем языке • 用你的语言阅读

Please make sure these dispatches reach as many readers as possible. Share with kin, friends and workmates and ask them to do likewise.

Jacques R. Pauwels Jacques R. Pauwels

May, 1945. Russian "war tourists" in Berlin. "These were, indeed, the men of the armies which had fought and beaten two-thirds of Germany’s land forces on the Eastern Front while the magnificently equipped British and Americans had trouble enough dealing with the other third in Normandy, Italy, and along the Siegfried Line. They were stocky, hard-faced peasants and herdsmen from the Steppes. They looked inured to hardship,” Australian war correspondent Osmar White described the victors.

Victory Day, May 9, 2021, Moscow's Red Square. In 1943, the Americans, British, and Soviets had agreed that there would be no separate negotiations with Nazi Germany with respect to its capitulation, and that the German surrender would have to be unconditional. In the early spring of 1945, Germany was as good as defeated and the Allies were getting ready to collectively receive its unconditional submission. But where would that capitulation ceremony take place – on the Eastern Front, or on the Western Front?

If only for reasons of prestige, the Western Allies preferred that Nazi Germany would acknowledge defeat somewhere on the Western Front. Secret talks with the Germans, which the British and Americans were already holding at that time (i.e. in March 1945) in neutral Switzerland in flagrant violation of inter-allied agreements, under the code-name Operation Sunrise, promised to be useful in that context. They could produce a German surrender in Italy, which had been the original objective of the talks but could also yield an agreement with respect to the coming general and supposedly unconditional German capitulation. Intriguing details, such as the venue of the ceremony, might possibly be determined in advance and without input from the Soviets. There actually existed many possibilities in this respect, because the Germans themselves kept approaching the Americans and the British in the hope of concluding a separate armistice with the Western powers or, if that would prove impossible, of steering as many Wehrmacht units as possible into American or British captivity by means of “local” surrenders, i.e. surrenders of larger or smaller units of the German army in restricted areas of the front.

Russian Federation army on May 9, 2021, commemorative units.

The Great War of 1914-1918 had ended with a clear and unequivocal armistice, namely in the form of an unconditional German surrender. The capitulation was signed in the headquarters of Marshal Foch in the village of Rethondes, near Compiègne, on November 11 shortly after 5 a.m., and the guns fell silent on that same morning at 11. The Second World War, on the other hand, was to grind to a halt, in Europe at least, amidst intrigue and confusion, so that even today there are many misconceptions regarding the time and place of the German capitulation. The Second World War was to end in the European theatre not with one, but with an entire string of German capitulations, with a veritable orgy of surrenders, and even after the signings it sometimes took quite some time before the hostilities were terminated.

It started in Italy on April 29, 1945, with the capitulation of the combined German armies in southwestern Europe to the Allied forces led by Alexander, the British field marshal. The ceremony took place in the town of Caserta, near Naples. Signatories on the German side included SS General Karl Wolff, who had conducted the negotiations with American secret agents in Switzerland about sensitive issues such as the neutralization of the kind of Italian anti-fascists for whom there was no room in the American-British post-war plans for their country. Stalin had found out about this “Operation Sunrise” and expressed misgivings about the arrangement that was being worked out between the Western Allies and the Germans in Italy, but in the end, he gave his blessing to this capitulation. The armistice was signed on April 29 but provided for a cease-fire only on May 2. This purported to allow sufficient time for American or British troops to hurry all the way to Trieste, where German troops were fighting off Tito’s Yugoslav partisans; the latter had good reason to believe that this city might become part of Yugoslavia after the war and undoubtedly had in mind the dictum that possession is ninety percent of the law. But the Americans and British wanted to prevent this scenario. A New Zealand unit reached Trieste “after a hectic dash up from Venice” on May 2 and helped to force the Germans in the city to surrender the next day, in the evening. A Kiwi chronicle of this event euphemistically relates that their men “arrived just in time to liberate the city together with units of Tito’s army,” but admitted that the objective had been to prevent the Yugoslav communists from seizing Trieste on their own and putting in place their own military administration, thus solidifying their claim to the region.

Many people in Great Britain firmly believe even today that the war against Germany ended with a German surrender in the headquarters of another British field marshal, namely Montgomery, on the Luneburg Heath in northern Germany. Yet this ceremony took place on May 4, 1945, that is, at least five days before the guns finally fell silent in Europe, and this capitulation applied only to German troops that had hitherto been battling Montgomery’s British Canadian 21st Army Group in the Netherlands and in Northwest Germany. Just to be on the safe side, the Canadians accepted the capitulation of all German troops in Holland the next day, May 5, during a ceremony in Wageningen, a town in the eastern Dutch province of Gelderland. To the British, it is of course important and gratifying to believe that the Germans had to beg for a cease-fire in the headquarters of their very own “Monty”; to the latter the prestige associated with the event provided some compensation for the fact that his reputation had suffered considerably from the fiasco of Operation Market Garden, the September 1944 attempt to cross the Rhine in the Dutch town of Arnhem, an undertaking of which he had been the godfather.

In the US and in Western Europe, the event on the Luneburg Heath is rightly viewed as a strictly local capitulation, even though it is recognized that it served as a kind of prelude to the definitive German capitulation and resulting ceasefire. As far as the Americans, French, Belgians, and others are concerned, this definitive German surrender took place in the headquarters of General Eisenhower, the supreme commander of all allied forces on the Western Front, in a modest school building in the city of Reims on May 7, 1945, in the early morning. But this armistice was to go into effect only on the next day, May 8, and only at 11:01 p.m. It is for this reason that even now, commemoration ceremonies in the United States and in Western Europe take place on May 8.

Russians sighteeing around the conquered city. Berlin—as expected—was a costly destination.

However, even the important event in Reims was not the final surrender ceremony. With the permission of Hitler’s successor, Admiral Dönitz, German spokesmen had come knocking on Eisenhower’s door to try once again to conclude an armistice only with the Western Allies or, failing that, to try to rescue more Wehrmacht units from the clutches of the Soviets by means of local surrenders on the Western Front. Eisenhower was personally unwilling to consent to further local surrenders, let alone a general German capitulation to the Western Allies only. But he appreciated the potential advantages that would accrue to the Western side if somehow the bulk of the Wehrmacht would end up in British-American rather than Soviet captivity. And he also realized that this was a unique opportunity to induce the desperate Germans to sign in his headquarters the general and unconditional capitulation in the form of a document that would conform to inter-Allied agreements; this detail would obviously do much to enhance the prestige of the United States.

In Reims, it thus came to a byzantine scenario. First, from Paris an obscure Soviet liaison officer, Major General Ivan Susloparov, was brought over to save the appearance of the required Allied collegiality. Second, while it was made clear to the Germans that there could be no question of a separate capitulation on the Western Front, a concession was made to them in the form of an agreement that the armistice would only go into effect after a delay of forty-five hours. This was done to accommodate the new German leaders’ desire to give as many Wehrmacht units as possible a last chance to surrender to the Americans or the British. This interval gave the Germans the opportunity to transfer troops from the East, where heavy fighting continued unabatedly, to the West, where after the signing rituals in Luneburg and then Reims hardly any shots were being fired anymore. The Germans, whose delegation was headed by General Jodl, signed the capitulation document at Eisenhower’s headquarters on May 7 at 2:41 a.m.; but the guns were to fall silent only on May 8 at 11:01 p.m. Local American commanders would cease to allow fleeing Germans to escape behind their lines only after the German capitulation went into effect. It can be argued, then, that the deal concluded in the Champagne city did not constitute a totally unconditional capitulation.

The document signed in Reims gave the Americans precisely what they wanted, namely, the prestige of a general German surrender on the Western Front in Eisenhower’s headquarters. The Germans also achieved the best they could hope for, since their dream of a capitulation to the Western Allies alone appeared to be out of the question: a “postponement of execution,” so to speak, of almost two days. During this time, the fighting continued virtually only on the Eastern Front, and countless German soldiers took advantage of this opportunity to disappear behind the British-American lines. However, the text of the surrender in Reims did not conform entirely to the wording of a general German capitulation agreed upon previously by the Americans and the British as well as the Soviets. It was also questionable whether the representative of the USSR, Susloparov, was really qualified to co-sign the document. Furthermore, it is understandable that the Soviets were far from pleased that the Germans were afforded the possibility to continue to battle the Red Army for almost two more days while on the Western Front the fighting had virtually come to an end. The impression was thus created that what had been signed in Reims was in fact a German surrender on the Western Front only, an arrangement that violated the inter-Allied agreements. To clear the air, it was decided to organize an ultimate capitulation ceremony, so that the German surrender in Reims retroactively revealed itself as a sort of prelude to the final surrender and/or as a purely military surrender, even though the Americans and the Western Europeans would continue to commemorate it as the true end to the war in Europe.

It was in Berlin, in the headquarters of Marshal Zhukov, that the final and general, political as well as military, German capitulation was signed on May 8, 1945, or put differently, that the German capitulation of the day before in Reims was properly ratified by all the Allies. The signatories for Germany, acting on the instructions of Admiral Dönitz, were the generals Keitel, von Friedeburg (who had also been present in Reims) and Stumpf. Since Zhukov had a lower military rank than Eisenhower, the latter had a perfect excuse for not attending the ceremony in the rubble of the German capital. He sent his rather low-profile British deputy, Marshal Tedder, to sign, and this of course took some luster away from the ceremony in Berlin in favour of the one in Reims.

As far as the Soviets and the majority of Eastern Europeans were concerned, the Second World War in Europe ended with the ceremony in Berlin on May 8, 1945, which resulted in the arms being laid down the next day, on May 9. For the Americans, and for most Western Europeans, “the real thing” was and remains the surrender in Reims, signed on May 7 and effective on May 8. While the former always commemorate the end of the war on May 9, the latter invariably do so on May 8. But the Dutch celebrate on May 5, date of the ceremony in the Canadian headquarters in Wageningen. That one of the greatest dramas of world history could have such a confusing and unworthy end in Europe was a consequence, as American historian Gabriel Kolko has writes, of the way in which the Americans and the British sought to achieve all sorts of big and small advantages for themselves – to the disadvantage of the Soviets – from the inevitable German capitulation.

The First World War had ended de facto with the armistice of November 11, 1918, and de jure with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919. The Second World War came to an end with an entire string of surrenders, but it never did come to a peace treaty à la versaillaise, at least not with respect to Germany. (Peace treaties were in due course concluded with Japan, Italy, and so on.). On February 10, 1947, all the victorious powers thus officially reconciled themselves in Paris with the countries that had been allies of Nazi Germany, namely Italy, Romania, Bulgaria, and Finland. And a peace treaty with Japan was concluded by the US and almost fifty other countries – but not the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China – in San Francisco on September 8, 1951; that treaty went into effect on April 28 of that same year. The so-called State Treaty signed between the four great victors of World War II – the US, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union – in Vienna on May 15, recognizing Austria as an independent and neutral country, may also be considered to have been a peace treaty. The First World War had ended de facto with the armistice of November 11, 1918, and de jure with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919. The Second World War came to an end with an entire string of surrenders, but it never did come to a peace treaty à la versaillaise, at least not with respect to Germany. (Peace treaties were in due course concluded with Japan, Italy, and so on.). On February 10, 1947, all the victorious powers thus officially reconciled themselves in Paris with the countries that had been allies of Nazi Germany, namely Italy, Romania, Bulgaria, and Finland. And a peace treaty with Japan was concluded by the US and almost fifty other countries – but not the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China – in San Francisco on September 8, 1951; that treaty went into effect on April 28 of that same year. The so-called State Treaty signed between the four great victors of World War II – the US, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union – in Vienna on May 15, recognizing Austria as an independent and neutral country, may also be considered to have been a peace treaty.

The reason why no real peace treaty was ever signed with Germany, is that the victors – the Western Allies on the one side and the Soviets on the other side – were unable to come to an agreement about Germany’s fate. Consequently, a few years after the war, two German states emerged, which virtually precluded the possibility of a peace treaty reflecting an agreement acceptable to all parties involved. And so a peace treaty with Germany, that is, a final settlement of all issues that remained unresolved after the war, such as the question of Germany’s eastern border, became feasible only when the reunification of the two Germanies became a realistic proposition, namely, after the fall of the Berlin Wall. That made the “Two-plus-Four” negotiations of the summer and fall of 1990 possible, negotiations whereby on the one hand the two German states found ways to reunify Germany, and whereby on the other hand the four great victors of the Second World War — the United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union — imposed their conditions on the German reunification and cleared up the status of the newly reunited country, taking into account not only their own interests but also the interests of other concerned European states such as Poland. The result of these negotiations was a convention that was signed in Moscow on September 12, 1990, and which, faute de mieux, can be viewed as the peace treaty that put an official end to the Second World War, at least with respect to Germany.

At that time, in 1990, the Soviets committed themselves to withdrawing their troops from all the Eastern European countries that had been their “satellites,” and they kept that promise; they also dissolved the Warsaw Pact. American troops, on the other hand, have remained in Germany ever since, and the US Congress has just recently officially decided that they will stay there for an indefinite period, even though most Germans would like to see the Yanks go home. The US also failed to respond to the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact with a dissolution of NATO. That alliance had presumably been created to defend Europe against a Soviet threat, and that threat had ceased to exist. Washington failed to keep a promise not to expand NATO to Russia’s borders as a wuid pro quo for the Red Army troops’ withdrawal; instead, Poland, the Baltic countries, the Czech Republic, etc., were enrolled as members of the alliance. As NATO clearly served offensive purposes, even in faraway countries such as Afghanistan, the alliance’s push into Europe’s eastern reaches looked increasingly threatening to the Russians.

It is not difficult to understand that Moscow viewed the planned incorporation of Ukraine into NATO to be unacceptable. This is how we got the present war in that country. Let us hope that this conflict, unlike World War II, will soon end with an unambiguous armistice and a solid peace treaty!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jacques R. Pauwels Jacques R. Pauwels is a people's historian. In the tradition pioneered by Marx and Engels, and continued by Michael Parenti, Howard Zinn, Eric Hobsbawm, Leo Huberman, and others of similar merit, he writes history that is not only firmly grounded in truth but is aimed at liberating the mind from the claptrap of existing ruling class mythology. Pauwels has taught European history at the University of Toronto, York University, and the University of Waterloo. His books include Big Business and Hitler, The Great Class War 1914-1918, and The Myth of the Good War. His new book is Myths of Modern History: From the French Revolution to the 20th Century World Wars and the Cold War - New Perspectives on Key Events.'

The views expressed herein fully reflect those of The Greanville Post.

[premium_newsticker id=”211406″]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

ALL CAPTIONS AND PULL QUOTES BY THE EDITORS NOT THE AUTHORS

Read it in your language • Lealo en su idioma • Lisez-le dans votre langue • Lies es in Deiner Sprache • Прочитайте это на вашем языке • 用你的语言阅读

| |

Jacques R. Pauwels is a people's historian. In the tradition pioneered by Marx and Engels, and continued by Michael Parenti, Howard Zinn, Eric Hobsbawm, Leo Huberman, and others of similar merit, he writes history that is not only firmly grounded in truth but is aimed at liberating the mind from the claptrap of existing ruling class mythology. Pauwels has taught European history at the University of Toronto, York University, and the University of Waterloo. His books include Big Business and Hitler, The Great Class War 1914-1918, and The Myth of the Good War.

Jacques R. Pauwels is a people's historian. In the tradition pioneered by Marx and Engels, and continued by Michael Parenti, Howard Zinn, Eric Hobsbawm, Leo Huberman, and others of similar merit, he writes history that is not only firmly grounded in truth but is aimed at liberating the mind from the claptrap of existing ruling class mythology. Pauwels has taught European history at the University of Toronto, York University, and the University of Waterloo. His books include Big Business and Hitler, The Great Class War 1914-1918, and The Myth of the Good War.![]() Don’t forget to sign up for our FREE bulletin. Get The Greanville Post in your mailbox every few days.

Don’t forget to sign up for our FREE bulletin. Get The Greanville Post in your mailbox every few days.