HELP ENLIGHTEN YOUR FELLOWS. BE SURE TO PASS THIS ON. SURVIVAL DEPENDS ON IT.

by Jacques R. Pauwels

This chapter is based on the author’s book on the French Revolution, Le Paris des sans-culottes. Guide du Paris révolutionnaire (1789-1799).

Myth: The French Revolution amounted to a senseless bloodbath during which thousands of innocent people were massacred by a Parisian mob, led by Jacobin scoundrels such as Robespierre. Fortunately, a great leader eventually appeared on the scene, like a deus ex machina, to restore order at home and, via an amazing string of victories in foreign wars, bring glory to France: Napoleon Bonaparte. For that achievement, France will forever remain grateful, even though things finished badly for Napoleon on account of a setback in Russia and a heroic last stand at Waterloo.

Reality: Despite the bloodletting that accompanied it, which was actually due more to counterrevolutionary “white” terror than to the revolutionary terror, the French Revolution constituted a first step in the direction of the political and social emancipation of the great majority of the people, in other words, of democracy, not only in France but in all of Europe and the entire world. This fact was most dramatically exemplified by Robespierre’s abolition of slavery. As for Napoleon, in many ways he was a product of the Revolution, but he was certainly not a democrat; he restored slavery, and his quest for national and personal glory cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of people.

Initial phase of the Revolution: Opening session of the General Assembly, 5 May 1789 shows the inauguration of the Estates-General in Versailles. The Estates General, comprising both nobles and commoners, had not been convened since 1614. The suggestion to summon the Estates-General came from high-ranking nobles, church dignitaries and high bureaucrats, the Assembly of Notables, convened by the King as a consultative body to resolve a serious fiscal and political crisis. (Click image for best appreciation).

Another view of the assembled Etats-Generaux. Consistent with the Ancien Regime's social order, the seating arrangement privileged the nobility and church, at the expense of the commoners, the Third Estate, who represented the vast majority of France. The Estates-General would eventually morph into the revolutionary National Assembly.

These changes occurred in France itself, but not its major transatlantic colony, founded in the early 17th century and known as Nouvelle-France, “New France”, namely the present-day Canadian province of Quebec. That territory was lost to the motherland during the Seven-Years’ War of 1756-1763. When, a few decades later, the Revolution called an entirely new France into being, nothing changed in Quebec. Change was unwanted there, especially since the British conquerors had turned over the colony’s administration to the Catholic Church, which anathemized the Revolution as the handiwork of Satan. In other words, when in Europe Old France became a New France, the overseas New France became an Old France. To modern Frenchmen, visiting Quebec is like a voyage back in time, as they are greeted by blue-and-white flags proudly displaying no less than four fleurs-de-lis, separated by a large cross. Within its mighty walls, Old Quebec City certainly radiates charm and comfort. But what was life really like in France before the “Great Revolution” that broke out in 1789?

About the political and social system of Ancien-Régime France, one thing is certain: it was not a democracy. Ordinary people, the demos (to use Greek terminology), or plebs, as the Romans used to say, had no power (Greek, kratos) whatsoever. Power was monopolized by a small minority of noblemen (a.k.a. aristocrats)1 as well as bishops and cardinals, the so-called “princes” of the Church.

Together, this patriciate of secular and ecclesiastical seigneurs represented no more than about five percent of the population. The system may therefore be described as an oligarchy, that is, an arrangement in which power (archè) is in the hands of “few people” (oligoi), or even an autocracy (autos, “self”, plus kratos), power enjoyed by a single person. Indeed, in France, the monarch, the primus inter pares of the nobility, had managed, at the expense of the rest of the noblemen, to concentrate most power into his own hands. The French monarchy had thus become an absolute monarchy. 2 It is in this context that the “Sun-King” Louis XIV had been able to pompously proclaim that the state belonged to him and to him alone, that his person was in fact the state: l’État, c’est moi! And on the eve of the Revolution, his successor, Louis XVI, still felt entitled to state that “this is the law because it is what I want”. In Ancien-Régime France, the monarch held an enormous amount of power, the seigneurs of the nobility and the church shared some of it, but the “little people” of the demos, the plebeians, enjoyed no power whatsoever.

While the French monarchy traditionally spent colossal sums of money on the construction of palaces such as Versailles and on grandiose “places royales”, that is, city squares featuring statues of sovereigns, such as the vast open space that is known today as Place de la Concorde, and also on endless wars, it never achieved anything worthwhile for the benefit of ordinary people.

The French were subjects of their king. They had all sorts of obligations to the monarchical state, such as payment of taxes and military service, but they hardly had any rights. They could be incarcerated for an indefinite period of time or even executed, simply because the king gave orders to that effect.

In the Ancien Régime, moreover, the principle of the equality of people was unheard of. Non-Catholics, for example, enjoyed even fewer rights than the Catholic majority. And different laws applied to the noble minority and the non-noble majority. Aristocrats condemned to death were decapitated, which happened to be the most humane form of execution at the time, while all others were either hanged or, worse, broken on the wheel, a bestial form of execution used in Paris for the last time only in the middle of the supposedly “enlightened” 18th century, in 1757.

The Ancien Régime was a society officially divided into classes, or rather, “estates”, three in number. The nobility and the clergy constituted the first two estates, while the rest of the rural as well as urban population – representing about ninety percent of France’s total population! — was lumped together into the “third estate”. The first and second estates were very much representative of the social upper class which was rich, powerful, and privileged in many ways. This class was mostly satisfied with the state of political and social affairs and felt that major changes were unnecessary and undesirable. (But they did wish for some reforms, as we will see later.)

On the other hand, one could not expect that ordinary people would resign themselves forever to a state of affairs that was unpleasant for most. In addition to the peasants in the countryside, the malcontents included urban folks such as the bourgeoisie, a term whose literal meaning is inhabitant of a town, bourg in French. The term bourgeoisie is often translated as “middle class”, but it is important to realize that there were two levels within that class. First, there was the upper level of the bourgeoisie, the “upper-middle” class (grande bourgeoisie, haute bourgeoisie), consisting of well-to-do people such as merchants, bankers, high-ranking government officials, and members of a well-paid liberal profession. Second, the bourgeoisie featured a large lower level, known as the petite bourgeoisie or “petty bourgeoisie”; its members were far less prosperous folks, though not paupers, for example shopkeepers and above all artisans, that is, craftsmen; they usually owned some property in the form of a house, a workshop, or at least the (sometimes valuable) tools of their trade. Finally, the urban plebs also included many folks who were very genuinely poor, and often extremely poor, such as wage-earning workers, unemployed, prostitutes, beggars, and other “proletarians”, that is, “people who own nothing but their offspring”. 3

The Third Estate thus amounted to a heterogeneous combination of what one might today call the “middle class” and the “lower class”. The upper-middle class – the members of the haute bourgeoisie, but not of the petite bourgeoisie – were rich, sometimes very rich, even richer than many aristocrats, and in this sense they, like the aristocrats, were “patricians”, to use an ancient Roman term for folks on the higher levels of the power pyramid. But they did not have any political power and did not enjoy the kind of social prestige radiated by the nobility; so they felt that it was time for change.

As for the peasants in the countryside and the petits bourgeois and other plebeians in the cities, their existence was precarious, as they confronted misery and hardships even when they were not totally poor, for example during the frequently occurring famines and times of high bread prices, which were typically blamed on taxes and on conspiracies of landowning noblemen and bourgeois merchants. This rising discontent triggered demonstrations and riots, and in 1789 these folks were to supply the shock troops that would storm the Bastille and achieve other impressive revolutionary deeds.

The Revolution that exploded in 1789 clearly reflected the great and traumatic class contradictions that characterized the Ancien Régime. The majority of the people, the peasants in the countryside and, in the city, the patrician haute bourgeoisie as well as the plebeians, above all the Parisian artisans who would be known as the “sans-culottes”, rose up against the upper class, the elite or “establishment”, consisting of the nobility and the high ranks of the clergy, lined up behind the king. Members of the bourgeoisie took over the leadership of the revolutionary movement, but the sans-culottes performed most if not all the revolutionary heavy lifting. In the countryside, the peasants made a significant contribution to the revolutionary cause by attacking the noble seigneurs in their castles. After the cancellation of the onerous feudal obligations the peasants had resented so much, however, tranquillity returned to the countryside. Henceforth, revolutionary action would take place mostly, though not exclusively, in Paris.

The French Revolution was obviously a domestic conflict within France, in which the lower classes, meaning the overwhelming majority of the population, put an end to the power and privileges of a tiny minority. Thus originated a process of democratization that, over the course of the following couple of centuries and until the present day, has known dramatic ups and downs, zigzags, and reversals, and is still far from completed.

The Revolution brought considerable change to the lives of the French, and this change amounted to a major improvement. The Revolution initiated the emancipation of the middle class and even of the lower classes. In 1789, the women and men of France ceased to be the “subjects” of a king. Instead, they became “citizens”, endowed with legally defined duties but also rights, of a state they could identify with, of a “nation”. And this state was no longer closely tied to a specific religion, as in the Ancien Régime, but was separated from the Church, and it enshrined the modern, sensible, and, indeed, democratic principle of freedom of conscience. The French also acquired the right to exert, via elections, a certain amount of political influence, that is, to provide some input into the management of the state. Moreover, the citizens of France were henceforth equal before the law, regardless of their social status or religious beliefs. Jews and Protestants thus ceased to be second-class citizens. (But more, much more, could have been done for women.) The considerable merits of the French Revolution also included measures that were inspired by the Enlightenment, such as the abolition of torture and, last but not least, the creation of a modern, “indivisible” and highly centralized French state.

This is only a very brief sketch of the major achievements of the years 1789-1791, which happened to be the first phase of the French Revolution. These achievements were important, but they certainly did not produce a democratic Utopia. They only amounted to the very first stage of the democratization process, that is, the long road, far from rectilinear, but winding and featuring ups and downs, towards a perfect democracy that remains a bright but distant star even today.

The achievements of the French Revolution in its early stage triggered great enthusiasm also outside of France, especially among the bourgeoisie, for example in England, where the poet William Wordsworth was to articulate that feeling of excitement and hope with immortal lines:

Europe at that time was thrilled with joy

France standing at the top of golden hours,

And human nature seeming born again . . .

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,

But to be young was very Heaven! 4

This progress towards democracy was achieved at the expense of the king, the nobility, and the Church, whose collective membership constituted a microscopic demographic minority that detested the idea, and a fortiori the reality, of democracy. Why? Because democracy meant “power by and for the people”, it signified a system that would necessarily put an end to their privileges and power.

On the other hand, the incipient democratization favoured the bourgeoisie, especially the haute bourgeoisie, the upper-middle class. In the Ancien Régime, this class, consisting of merchants, bankers, high-ranking government officials, lawyers, and such, had been prospering economically but not politically. It was determined to use the state power it had achieved thanks to the revolution to further its class interests, just as, in the Ancien Régime, the monarch, the nobility and the clergy had used their power in the state for their own benefit, for example by exempting themselves from most forms of taxation. As they ensconced themselves on the commanding heights of the state, the upper-middle class burghers were able to craft laws and regulations that they, as merchants, bankers, entrepreneurs, high-ranking officials, etc., found advantageous. These measures included the abolition of domestic tolls on the transportation and sale of goods – such as the infamous customs wall surrounding Paris – as well as the introduction of a new, uniform system of weights and measures; and also the Law of Le Chapelier, which prohibited the formation of trade unions and other organizations of wage earners and artisans.

After two years of revolution, in 1791, the haute bourgeoisie had realized its major objectives. Royal absolutism, with its privileges for the nobility and the clergy, had given way to a constitutional, parliamentary monarchy in which prosperous burghers held power. Thanks to the introduction of limitations on the right to vote, in the form of a census suffrage (or censitary suffrage), which gave the vote only to those who paid a relatively high amount of taxes, ordinary folks remained politically powerless. Only the well-to-do, the “people with property” (gens de bien) could vote and qualify for membership in the popular assemblies, first the Constitutional Assembly (Assemblée constituante) and then the Legislative Assembly (Assemblée legislative), while the “people without property” (gens de rien) – or with only minimal property, such as the majority of the sans-culottes – were rigorously excluded.

In the fall of 1791, this compromise, essentially a constitutional monarchy of the kind that still exists today in quite a few European countries, seemed to be firmly in place and was in fact enshrined in a formal constitution. And powerful symbols were created for it: the tricolor flag, a combination of the white and blue of the monarchy and the red and blue of the coat of arms of Paris.

The revolutionary issue remained far from settled for two main reasons: first, relentless pressure for more far-reaching revolutionary changes, emanating from the Parisian populace, the sans-culottes, and second, the compromise of a constitutional, parliamentary monarchy was also threatened by counterrevolutionary pressure at home and abroad. The Parisian plebeians longed for a more radical revolutionary outcome, while the counterrevolutionaries wanted to undo the revolution, wishing for a retour en arrière to the Ancien Régime.

The Parisian sans-culottes constituted the shock troops that had achieved the great revolutionary deeds, including the storming of the Bastille. It was thanks to them that the upper-middle class had been able to come to power. But the well-to-do burghers despised and feared the lower-class denizens of the capital as a restless and dangerous “populace” or “mob”, as unsympathetic historians call them. The objectives of this populace included all sorts of desiderata deemed unacceptable to the “moderate” revolutionaries of the bourgeoisie, for example, the introduction of what will later be widely considered to be the sine qua non of democracy: universal suffrage. This democratic system seemed likely to enable the rise to positions of power not of solid burghers but of representatives of the popular masses, that is, the kind of folks who could not be counted on to display much respect for private property, cornerstone of the liberal gospel preached by Adam Smith. It was indeed at that time that the French bourgeoisie was embracing liberal ideas because they reflected and promoted the interests of their class.

The plebeian revolutionaries also expected the embryonic democratic state to somehow arrange for higher wages and lower prices, especially a lower price of bread, the primordial food of the French at the time. But that too was not to the taste of the bourgeoisie, because such measures amounted to state intervention in economic life and therefore violated the liberal dogma of laissez faire, the idea that “markets” and “enterprise” should be “free”. It was clear, moreover, that the bourgeoisie would be saddled with a share of the costs of “statist” measures. Conversely, the numerous Parisian wage-earners were antagonized by a number of measures taken by the new bourgeois authorities, for example the notorious Le Chapelier law, which outlawed workers’ associations and strikes.

The plebeians were excluded from the successive assemblies of “representatives of the people”, but they put considerable pressure on these bodies via boisterous demonstrations in the streets and squares of the capital. This frequently involved eruptions of violence. On July 17, 1791, for instance, tens of thousands of sans-culottes gathered on the huge open space known as Champ de Mars to express their discontentment about unemployment, high prices, and low wages.

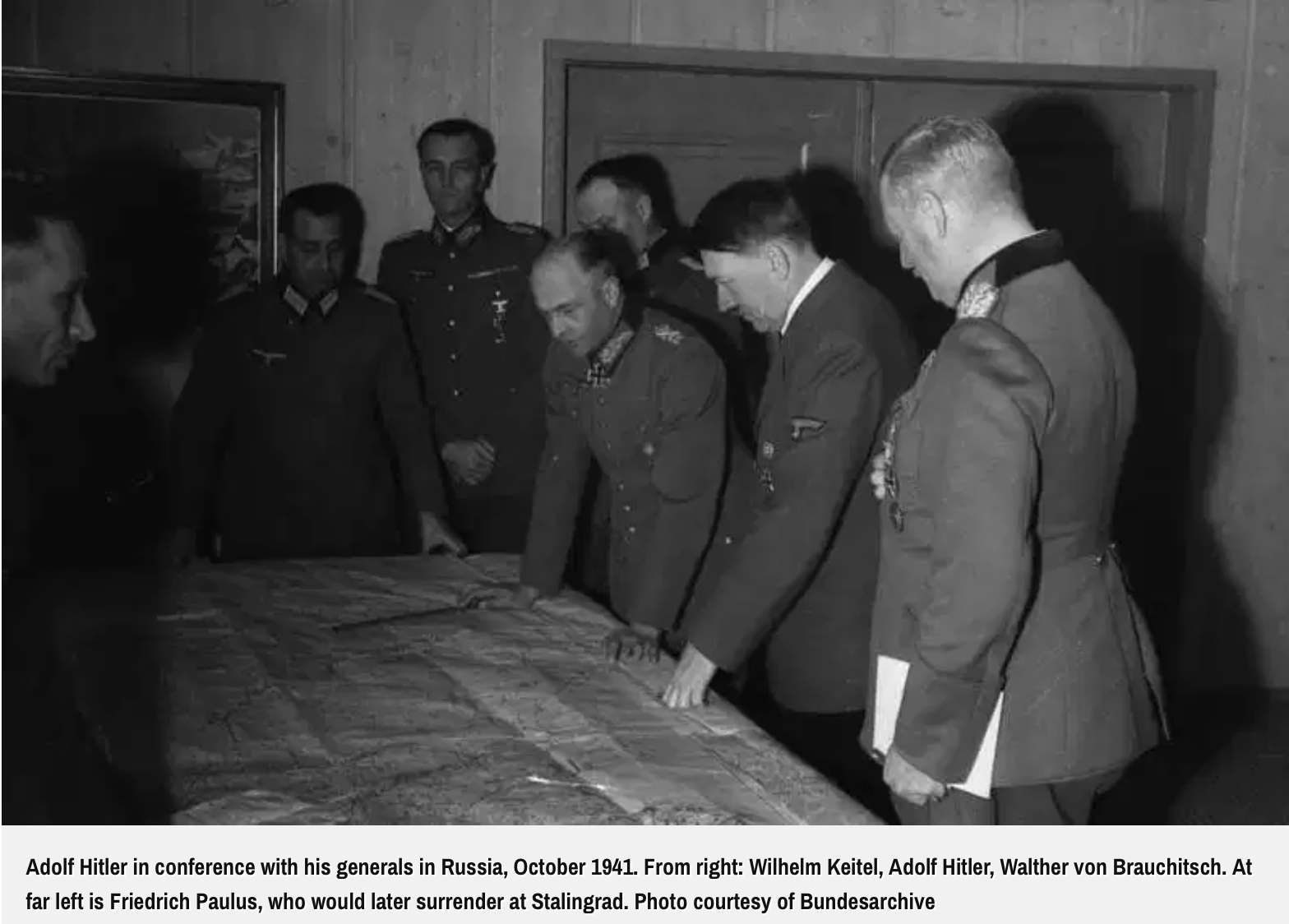

Leaders of the Gironde taken to the gallows. The disgraced Girondins promoted war as a maneuver to stunt the revolutionary process at the level that benefited their merchant/haute bourgeois interests. They failed, and paid a high price, but their class would eventually emerge victorious to the detriment of most ordinary citizens and real democracy. They would be pleased with today's global capitalism.

To eliminate this pesky pressure from the popular masses, a stratagem was found in the spring of 1792 by a group of grand-bourgeois politicians, i.e. men of upper-middle class background, mostly rich merchants from Bordeaux; these men were known as the Girondins, because that is what the inhabitants of that city, located on the shores of the Gironde river, are traditionally called. The remedy they conjured up was war. Indeed, war was eminently useful for the purpose of redirecting the energy of the sans-culottes towards less risky objectives than the additional, more radical revolutionary objectives unwanted and even feared by the bourgeoisie. War also implied the removal of most of the revolutionary hotheads from the revolutionary crucible, Paris. An international war, a conflict against foreign or “external” enemies, was to put an end to the national war, which the revolution happened to be, the conflict between domestic or “internal” enemies, class enemies, within France. The Girondins hoped to halt the revolutionary process, prevent the revolution from intensifying, from becoming more radical, which is what the sans-culottes aspired to do. The “men from Bordeaux” wanted to prevent the revolutionary Pandora’s Box from yielding what the bourgeoisie viewed as a surfeit of democracy. They preferred conflict against foreign foes to conflict against domestic enemies, international war to class war.

The Girondins hoped not only that war would neutralize the overly radical revolutionaries but also provide an opportunity to settle accounts with all those who did not fully support the new revolutionary France, to stigmatize them as traitors to the fatherland, and to treat them accordingly; the number of these counterrevolutionaries, who longed for a return to the Ancien Régime, included the king himself.

Like countless other revolutionaries, the Girondins also believed that revolutionary France had a universal mission, in other words, was predestined to recreate the rest of the world in its own image, and was entitled to use violence, if necessary, to achieve this noble objective. It was believed that France’s revolutionary troops would be welcomed abroad by the popular masses as liberators.

Finally, it was expected that war would yield conquests and therefore bring in revenue, because the Girondins and bourgeois revolutionaries in general wanted to repay the huge national debt that was the legacy of the absolute monarchy. The reason why did they not simply repudiate that debt is that the creditors were essentially the kind of merchants, bankers, and other well-to-do burghers exemplified by the Girondins, from whom the royal government had borrowed the money.

The intrigues of counter-revolutionaries at home and abroad eventually involved the king, who hoped a war with Austria, and a revolutionary defeat, would restore his authority. Charged with treason, Louis XVI was executed on January 21, 1793, at the Place de la Révolution (today rechristened Place de la Concorde).

The Revolution, which had started in France as a domestic class conflict, also started to morph into an international war because of the reaction of Europe’s crowned heads to developments within France. These sovereigns were far from enchanted by the anti-absolutist and anti-aristocratic precedent being created. They considered it a nefarious example that might be emulated by their own subjects. And the prelates of the Christian churches – Catholic and non-Catholic – associated with the absolutist monarchies supported the Pope’s condemnation of the anticlerical Revolution as well as his appeal for a counterrevolutionary crusade against France.

Support for an international armed intervention aimed at the restauration of the Ancien Régime in France also came from the émigrés, the numerous French aristocrats who had fled to England or elsewhere, and even, albeit secretly, from Louis XVI himself. That became obvious when he attempted to flee the country and, a little later, when incriminating correspondence with foreign monarchs was discovered in his apartments.

When war broke out in 1792, countless volunteers stepped forward to defend the fatherland as well as the Revolution. They came from all over France, but prominent among them were the Parisian sans-culottes. Against all expectations, this motley crew managed to defeat an Austrian army that had marched into France. It is in this context that a new national anthem originated, namely as a song sung by a battalion of patriots from Marseille: the “Marseillaise”.

Assault on the Tuileries, and massacre of the Swiss Guards, perceived by many as foreign mercenaries. They were.

But the war dragged on, involved some nasty defeats, and provoked more and more misery among the “little people”. A new invasion of the country, combined with counterrevolutionary uprisings in the provinces, especially the Vendée, triggered a kind of panic in Paris, to become known as la Terreur, the Terror. The revolutionary pressure thus increased, which was reflected in some particularly dramatic and bloody events. The first of those was the storming, on August 10, 1792, of the Tuileries Palace, the residence of the king, who was now not incorrectly viewed as the figurehead of the counterrevolution. The second event of this nature took place from 2 to 5 September and was to go down in history as the “September Massacres”: the slaughter of hundreds of real as well as perceived counterrevolutionaries held in Parisian prisons.

While the Revolution became more and more radical, it also became more democratic in many ways. In the Legislative Assembly, which had replaced the Constituent Assembly in September 1791, the bourgeois delegates deemed it necessary to make major concessions to a Parisian “populace” they loathed and feared — but needed in the struggle against foreign as well as domestic counterrevolutionaries. The monarchy was replaced by a democratic state system, the republic, and the king was formally accused of treason, brought to trial, found guilty, and executed. The Legislative Assembly itself had to give way to the National Convention, a meeting of people’s representatives elected via a (quasi-) universal, rather than censitary, suffrage, albeit reserved for men only.

Robespierre and the Jacobins sought to internalize, rather than externalize, the revolution. Contrary to the Girondins, the Jacobins were willing not only to collaborate with the sans-culottes in the implacable struggle against the counterrevolution but also to take unprecedented, radical revolutionary measures for the benefit of these sans-culottes and of French plebeians in general.

Even so, virtually only members of the well-to-do bourgeoisie continued to be elected, because ordinary folks did not benefit from the free time and independent income indispensable for an involvement in parliamentary activities. The Girondins could thus remain in power, but they were rapidly losing prestige and popularity in the eyes of the Parisian “populace”. Their fate contrasted starkly with the rising popular appeal of their radical competitors, folks of mostly lower-middle class, petty-bourgeois background, the Jacobins. Led by personalities such as Maximilien Robespierre. the Jacobins had been opposed to the war. The Girondin argument that French troops would be welcomed abroad as liberators had been rebuffed by Robespierre with the argument that “nobody likes armed missionaries”. He and his companions felt that it was necessary to concentrate on, and indeed intensify, the Revolution within the country instead of exporting it; they sought to internalize, rather than externalize, the revolution. Contrary to the Girondins, the Jacobins were willing not only to collaborate with the sans-culottes in the implacable struggle against the counterrevolution, but also to take unprecedented, radical revolutionary measures for the benefit of these sans-culottes and of French plebeians in general.

It is thanks to the support of the sans-culottes that, in the spring of 1793, Robespierre and the most radical Jacobins, a faction came to power that was known as the Montagnards because in the assembly they occupied the highest rows of benches, the “mountain”. The Convention thus moved from a Girondin to a Jacobin phase. And indeed, under the direction of Robespierre and his collaborators within the Committee of Public Safety (Comité de salut public), the government’s principal executive organ, set up by the Convention in April 1793, numerous radical measures were introduced that heralded a considerable progress in the direction of democracy. For the benefit of the peasants, their feudal obligations to the aristocrats were entirely and definitively abolished; it was no longer necessary to purchase these obligations back from the lords as compensation for the latter's loss of “property”, as had been the case under the previous reform. And via the introduction of price controls, the government attempted to lower the price of bread, a measure that was crucially important for the Parisian sans-culottes and urban plebeians in general; however, such measures violated laissez-faire principles that remained dear to the hearts of the Jacobins, so that their implementation left a lot to be desired.

More important is the fact that a new constitution was promulgated, the Constitution of [the Republican] Year One, or Constitution of 1793. Contrary to its liberal predecessor of 1791, this new code focused much more on equality than on liberty, even though freedoms such as those of the press and of religion were enshrined. It provided for a system of universal suffrage for men and even for certain social-economic rights such as the right to work, to education (at state expense), and to public support for the needy. The state thus clearly assumed an active role in the social-economic life of the nation, which contravened the liberal principles of the Girondins, representatives of the upper-middle class, and even the lower-middle class Jacobins, but suited the Parisian sans-culottes. On the other hand, the new constitution also enshrined the right to hold property and upheld the Le Chapelier law. This reflected the interests and liberal principles that the petty-bourgeois Jacobins shared with the grand-bourgeois Girondins.

The Jacobins’ commitment to democracy was limited in other ways. They remained attached to the age-old patriarchal system and therefore undertook nothing for the emancipation of women, who were not given the right to vote. It was even under the regime of Robespierre that a famous feminist, Olympe de Gouges, author of a Declaration of the Rights of Women (1791), was condemned to death and guillotined in November 1793. However, it is not clear if this was done because of her feminism or because of her support for the Girondins.

Maximilien Robespierre, justly called the Incorruptible. The idealist leader of the Jacobins. Despite some shortcomings, a pivotal figure in the complex revolutionary process. His fall allowed the grand bourgeois to conquer power, which they have retained ever since. |

Africa remembers: Several nations in Africa have issued stamps honoring Robespierre. They are grateful for the French revolutionary's support in the elimination of slavery. |

|

|

In spite of these shortcomings, it may be said that during the French Revolution, the march towards democracy culminated during its most popular – in the sense of “of the people” – phase, its most radical and egalitarian phase, in other words, under the auspices of Robespierre, in 1793-1794.

The Jacobin Convention’s greatest achievement by far in the service of democracy, however, was undoubtedly its abolition of slavery on February 2, 1794. The Girondins opposed this initiative because many of them owed their fortune to the slave trade, and the bourgeoisie in general considered slaves to be a legitimate and therefore sacrosanct form of property. Under the auspices of Robespierre, France became the first country in which an institution that had oppressed and exploited human beings for thousands of years was abolished.

In its early, moderate phase, the Revolution had transformed the French from subjects into citizens; in its radical phase, the Revolution transformed slaves into free women and men. Did this not amount to a giant step forward for democracy, for the emancipation of oppressed, exploited, abused, poor, hungry people? “A historic liberation for humanity” is how, in a book entitled Big History. From the Big Bang to the Present, Cynthia Stokes Brown describes the abolition of slavery in England, the US, and elsewhere, but without mentioning Robespierre and the French Revolution. 5 The majority of other historians similarly fail to pay much attention to this great achievement of the French Revolution in its most radical phase, an achievement to be credited to the most ardent revolutionaries, the Jacobins, and to the most radical faction of these zealots, the Montagnards, of whom Robespierre was the figurehead.

By intensifying and radicalizing the Revolution, by forcing France, so to speak, to make further progress on the road to democracy, Robespierre and his Jacobin companions brought upon themselves the hatred not only of the counterrevolutionaries in France and abroad but also of the majority of the upper-middle class revolutionaries. The latter had been satisfied with the formula of a parliamentary monarchy, enshrined in the Constitution of 1791; as far as they were concerned, the objectives of 1789 had been achieved, the revolutionary process had gone far enough and now needed to come to a halt.

The motto of the French Revolution was “liberty, equality, fraternity”, and in 1791 the haute bourgeoisie felt that the French had achieved sufficient liberty and that their liberty was threatened by the kind of price controls and other forms of state intervention in the economy wanted by the plebeians and introduced by the Jacobins. As for equality, the well-to-do burghers were very pleased that they were no longer, as in the Ancien Régime, unequal, that is, inferior, to the nobles they had simultaneously hated and admired; but they did not want to become the equals of the Parisian sans-culottes and other plebeians, folks they despised and feared and with whom they felt no solidarity whatsoever. Consequently, they wanted to limit equality to a purely formal equality before the law, and they were not at all prepared to consider any initiatives aimed at achieving the ideal of social equality.

We can thus understand that it was not the counterrevolutionaries who, in July 1794, the month of Thermidor according to the revolutionary calendar, arranged for the fall of Robespierre, but the bourgeois elements who longed for a retour en arrière. They wanted to return, not to the pre-1789 Ancien Régime, but to the moderate revolutionary phase of 1791, featuring a republic instead of a constitutional monarch. (After the experiences with Louis XVI, no revolutionary wanted anything more to do with kings.)

The “Thermidorian” reaction – or just “Thermidor” – thus gave birth to a republic custom-made for the haute bourgeoisie; it has been aptly described as a “bourgeois republic” or a “republic of property-owners” (république des propriétaires). The right to vote was restricted to citizens owning a considerable amount of property. And, in the name of laissez faire, the new upper-middle class regime stubbornly refused to undertake anything at all for the benefit of the “little people”, even though plebeians in Paris and all over France suffered from rapidly increasing poverty and misery. Unrest and rebellion resurfaced among the sans-culottes and the Jacobin fire threatened to flare up again. Moreover, the fall of Robespierre and the Jacobins, the great champions not only of the radical Revolution but of the Revolution tout court, had emboldened all counterrevolutionary and antirepublican forces. The latter were now aggressively and openly agitating in favor of a constitutional monarchy or, better still, a full-fledged restoration of the Ancien Régime.

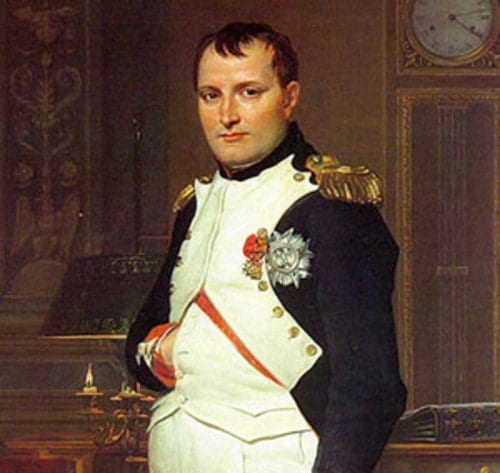

The Thermidorians thus found themselves tacking precariously between a Jacobin Scylla and a counterrevolutionary Charybdis. It is under those difficult circumstances that a new constitution was concocted in 1795. It provided for an extremely undemocratic governmental system, headed by a committee of “directors”, and was therefore called the Directoire or “directorship”. When it turned out that this formula failed to eliminate the twin menace to bourgeois rule, however, it was decided to stop trying to save the appearance of revolutionary democracy. Via a coup d’état orchestrated in the month of November – “Brumaire” according to the republican calendar – of 1799, a military dictatorship was established with Napoleon Bonaparte at its head, a popular general who could be expected to rule on behalf, and for the benefit, of the upper-middle class. In order to create the illusion that the new regime was inspired by the republican traditions of Ancient Rome, Bonaparte received the title of First Consul, but in 1804 he was to put an end to this charade by crowning himself emperor.

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) on engraving from 1873. Emperor of France. Handpicked by the haute bourgeoisie to rule the nation by flattening the revolutionary process at home, while substituting war lust and chauvinism. He also kept the ancien regime royalists at bay.

With the coup d’état of Brumaire, France’s well-to-do bourgeoisie transferred political power to Bonaparte in order not to have to lose it to the royalists or surrender it to the Jacobins. Bonaparte became the supreme ruler of France, but in reality he was in the service of the gentlemen of the country’s upper-middle class, above all big businessmen, bankers, and high-ranking government officials.

Financially, he and the entire French state found themselves to be dependent on a private institution that was – and remains today – the property of the wealthy elite of the country, even though that fact was semantically obfuscated by giving it a name that created the impression that it was a state institution, namely the French “national bank”, the Banque de France. Charging relatively high interest rates, the bankers of this institution provided the emperor with the funds he needed to govern France, to arm the country, to wage wars – and to enjoy being emperor. As expected, he would indeed rule on their behalf and to the advantage of their class, that is, all owners of land and other forms of capital, the property-owners in general.

In 1802, Bonaparte demonstrated his respect for private property, cornerstone of the liberal ideology dear to bourgeois hearts, in spectacular fashion by reintroducing slavery. Translating words into action, he sent an army to Santo Domingo to put down a slave uprising on that Caribbean island, then a French colony. But the former slaves resisted bravely and ultimately effectively: the expedition failed, and thus was born the world’s very first state founded by former slaves who had liberated themselves: Haiti. (That development was not welcomed in the US, where slavery was to survive much longer, because the success of the former slaves in Haiti was perceived to constitute a bad example, and the island nation would pay a painful price for that original sin.)

Napoleon was also handpicked on account of his excellent antiroyalist credentials. In 1795, while still merely an artillery officer in Paris, he had bloodily dispersed a crowd of royalist demonstrators “with a volley of grape shot”, as he laconically reported to his relieved and impressed superiors. First as consul and then as emperor, he used, vis-à-vis royalists and counterrevolutionaries in general, not only the “stick” of repression but also the “carrot” of concessions and conciliation. During his reign, for example, the emigrated aristocrats, who had already been allowed to come back to France after Thermidor, could share in the benefits that were showered on property-owners in general. Many of them returned to their castles to lord it once again, in collaboration with parish priests and other notables, over the denizens of their bailiwick of rural France. They were thus integrated into the Bonapartist system.

Napoleon also reached a modus vivendi with the counterrevolutionary institution par excellence, the Catholic Church, by signing a concordat with the Pope. Catholicism did not regain its former status of state religion, but it was recognized as the religion of the majority of the French population and therefore showered with generous financial state support.

To exorcize the Jacobin menace – that is, the threat of revolutionary radicalization and democratization – Napoleon relied mainly on the instrument pioneered by the Girondins and also used most diligently by the Directoire, namely warfare. Indeed, when we think of Bonaparte’s regime, what comes to mind are not, as in the case of the years 1789 to 1794, revolutionary events in the centre of the great city in the centre of France, but rather, an interminable series of wars fought far away from Paris and far beyond the borders of France, and this is not a coincidence. Wars happened to be extremely functional for the primordial objective of the bourgeois reaction to Robespierre’s experiments with revolutionary radicalism: safeguarding the achievements of the bourgeois revolution of 1791, while preventing a return to the Ancien Régime as well as a remake of 1793.

Robespierre and the Montagnards wanted not only to protect the Revolution, but also to intensify it, radicalize it. And that implied “internalizing” the Revolution in France, and above all in the capital, Paris, heart of France and cradle of the Revolution. It was not a coincidence that the decapitations that are so closely associated with the radical Revolution took place in the middle of a square in the middle of the city situated, at least figuratively speaking, in the middle of the country.

In order to concentrate their energies, and those of the sans-culottes and all the true revolutionaries on the “internalization” of the Revolution, Robespierre and his Jacobin companions – contrary to the Girondins – opposed international wars as a waste of revolutionary energy and a threat to the Revolution. Conversely, the interminable series of wars waged afterwards – first under the auspices of the Directoire, then under those of Bonaparte – signified an “externalization” of the Revolution, an exportation of the bourgeois revolution that had culminated in 1791. Those wars served to prevent an “internalization” or “radicalization” of the Revolution, as had happened in 1793.

It was to put an end to the Revolution in France itself, then, that Napoleon abducted it from its Parisian cradle and exported it to the rest of Europe. In order to prevent the mighty revolutionary current from excavating and deepening its own channel – Paris and the rest of France – first the Thermidorians and later Napoleon caused its troubled waters to overflow the borders of France, inundate all of Europe, thus becoming vast, but shallow and calm.

Napoleon in Berlin. Branderburg Gate can be seen in the background.

The wars caused the restless revolutionaries, the sans-culottes, to disappear from the revolutionary crucible that was Paris. They were stuffed into uniforms and shipped off to the four corners of Europe, from Cadiz to Moscow, and many of them would never come back. Moreover, war helped to put an end to the social problems that had plagued the country and, in the capital, had served as catalyst of the Revolution. The problem of unemployment, for example, was largely solved by the introduction of military service, initially voluntary but soon enough compulsory.

War also provided a kind of “Keynesian” stimulus to the national economy: military expenditures enhanced the demand for products such as cannon, uniforms, and ships, thus boosting employment. And successful wars, followed by the occupation and looting of foreign countries, fattened the treasury of the French state. With this lucre, Napoleon could reimburse the Banque de France for its “services”, which helped to further enrich the already well-to-do bourgeoisie. It also made it possible to bankroll his military projects, sanitize the state finances, and, last but not least, throw a few crumbs to the “little” Frenchmen, especially in the capital. These crumbs included subsidized and therefore lower prices of bread and other essential foodstuffs, which served to still not only the physiological but also the revolutionary appetite of the “populace”. The social problems of Paris and of France in general were thus resolved by warfare and at the expense of foreigners. (Nearly one century later, “imperialist” warfare and conquests would similarly enrich the upper-middle class and appease the plebs at the expense of foreigners, mostly in the colonies, as we will see in a later chapter.)

From the perspective of the bourgeoisie, the wars were also a godsend because they allowed all sorts of businessmen, especially good friends of the regime, to rake in gargantuan profits. Wars were good, even excellent, for business. Fortunes were amassed via contracts to supply equipment to the army, and after the fall of Robespierre, such contracts were strictly reserved for privately owned firms, big firms, of course, owned by well-to-do burghers, not small enterprises run by petty-bourgeois artisans. As long as Napoleon’s wars were successful, they not only yielded high profits, but also made foreign raw materials and markets available for the benefit of the rapidly developing French industry. And this would allow industrialists (and bankers) to play an increasingly important role within the ranks of the country’s bourgeoisie. In France, under Napoleon, industrial (and financial) capitalism, typical of the 19th century, would progressively eclipse the mercantile capitalism of the preceding centuries.

It ought to be mentioned at this stage that the accumulation of commercial capital in France had largely been possible thanks to the slave trade, while the accumulation of industrial and financial capital had been enabled by the quasi-uninterrupted series of wars – essentially wars of rapine — waged first by the Directoire and then by Napoleon. In this sense, Balzac was certainly right when he made his famous remark that “behind every great fortune, there lurks a great crime”.

Let us return to the anti-Jacobin, anti-radical, and ultimately antidemocratic function of the wars waged under the auspices of the Thermidorians and above all Bonaparte. Officially, these wars purported to share with the rest of Europe the benefits of the Revolution, that is, the bourgeois Revolution of 1789-1791. With this noble idea in mind, the sans-culottes went to war enthusiastically, but they were to find out soon enough that Robespierre was right when he predicted that “armed missionaries” would not be welcomed with open arms in foreign countries. Among the sans-culottes who stayed at home, however, the news of great victories generated a patriotic pride that compensated for the waning revolutionary enthusiasm. With a little help from the god of war, Mars, the revolutionary energy of the sans-culottes and of the French people in general was thus diverted into other channels, flowing into directions that loomed less threatening to the bourgeoisie. We are dealing here with a displacement process: the French people, including the Parisian sans-culottes, gradually lost their enthusiasm for the revolution, that is, the class struggle within the country, the struggle for the ideals of liberty, equality, and solidarity between Frenchmen and neighbouring people. The French increasingly worshipped the golden calf of French chauvinism, aspiring to increase the size and the international glory of the “great nation” and, with it, the glory of its supremo, Bonaparte.

Thus we can also understand the ambiguous reaction of the European peoples to the contemporary wars and conquests of France. Certain folks – more particularly, the local Ancien-Régime elites of nobility and clergy, plus most of the peasants – repudiated the Revolution in toto, while others – above all the local counterparts of the Jacobins, such as the Dutch “Patriots” – welcomed the revolution virtually unconditionally. But many found themselves torn between admiration for the ideas and achievements of the French Revolution and rejection of French militarism, unbridled chauvinism, and naked imperialism – also in the field of language, because French was the idiom of the Revolution while other languages were deemed to be counterrevolutionary. Numerous non-French simultaneously harboured admiration and repulsion towards the French Revolution.

In some cases, initial enthusiasm gave way, sooner or later, to disillusion. Countless Brits, for example, moved from positive feelings towards the Revolution in France, a “moderate” revolution that had given birth to a constitutional monarchy à l’anglaise, to an aversion with respect to the alleged excesses of Robespierre and his radical republican cronies. A century and a half later, George Orwell could state that, “to the average Englishman, the French Revolution means no more than a pyramid of severed heads”. The same thing could be claimed about nearly all non-Frenchmen of his time, and even today this would be an accurate description of the view of most people in France and elsewhere.

Napoleon’s supposedly glorious career came to an end on the battlefield of Waterloo. The victors were the international champions of the counterrevolution, the crowned heads of Russia, Austria, Great Britain, etc. Everywhere, they set the clocks back to the time of the good old days – for themselves, that is – of the Ancien Régime. And it was under their auspices that the history of the French Revolution began to be written. However, revolutions soon erupted again, spectacularly so in 1848, the so-called “crazy year”. In Central and Eastern Europe, the revolutionary movements were crushed via armed interventions – that is, wars — by Russia and Austria. But the revolution that broke out in Paris was successful and, like France’s earlier “Great Revolution”, generated remarkable progress in the direction of democracy. The republic replaced the monarchy again, slavery was definitively abolished, and universal suffrage was introduced.

Reluctantly, the upper-middle class, which had once again been able to come to power thanks to revolutionary action by the plebs, gave its blessing to this new wave of democratization. However, the well-to-do burghers had enough when the Parisian populace demanded certain social measures, e.g. unemployment relief, that violated laissez-faire principles. Demonstrations were smothered in blood, and power was again transferred to a Bonaparte, Louis-Napoleon, a nephew of the “great” Napoleon, who, in 1850, was put on the throne to reign as Emperor Napoleon III. The revolutionary tide was thus made to turn once more, which ended the progress towards democracy that had been achieved thanks to the 1848 Revolution.

Fear of revolutionary encores, likely to be spearheaded by the “dangerous classes”, that is, the lower class, caused the bourgeoisie to cease being a revolutionary class itself. Indeed, the “heroic era” of the bourgeoisie came to an inglorious end as the well-to-do burghers joined the nobility and the clergy in the counterrevolutionary camp. In Germany, Austria, and elsewhere, wherever the bourgeoisie had participated in aborted revolutions in 1848, the upper-middle class in its virtual entirety as well as a major share of the lower-middle class morphed into counterrevolutionaries. Thus we can understand that contemporary historians, overwhelmingly personalities of solid bourgeois background, started to depict France’s Great Revolution in a negative light. But they did so less from the 24-carat counterrevolutionary perspective of the nobility and the clergy, who condemned the Revolution in toto, than from a (grand-)bourgeois viewpoint. And this implied thumbs up for the revolutionary developments up to and including 1791 and after 1794, and also for Napoleon, but thumbs down for the radical, especially Jacobin revolutionary phase of 1792-1794.

In this context, the myth was born that, in spite of some excesses due to mob action, the Revolution had been on the right track and produced excellent results from 1789 to 1791, that is, under the auspices of the (haute) bourgeoisie; it had unfortunately – and tragically — “derailed” with the advent to power of the much too radical Jacobins, but returned to the correct “straight and narrow” path thanks to Thermidor and especially Napoleon, the grand champion of the cause of the bourgeoisie.

It became de rigueur to demonize Robespierre (and other Jacobins and radical revolutionaries in general) and to deify Bonaparte. In the course of the 19th century, most French cities erected statues to honour the Corsican and named public squares and avenues after him; his name was also given to countless cafés and restaurants of the kind where well-to-do burghers can sit down at a table of their own – temporary private property, so to speak – and feel comfortable.

Conversely, Robespierre fell into public disgrace, he became the victim of a damnatio memoriae. No statues or other monuments honour him, and no squares or streets bear his name, although there exist a few exceptions to this general rule. For example, a small bust adorns a Robespierre Square in the Parisian suburb of Saint-Denis, and in Paris a subway station was named after the man who was known as the “incorruptible”. And after years of all kinds of opposition and difficulties, a modest museum devoted to Robespierre will hopefully be opened soon in the northern French town of his birth, Arras.

The creation – and perpetuation — of the twin myth of the wonderful Napoleon and the awful Robespierre is owed above all to the writers and teachers of history. Robespierre and the radical, Jacobin phase of the French Revolution could hardly be publicly repudiated for their contribution to the process of democratization, epitomized by the abolition of slavery. This significant contribution to the cause of democracy, for which Robespierre really deserved a statue in the middle of Place de la Concorde, was systematically and thoroughly obfuscated, so that even today, only relatively few French, and even fewer non-French women and men are aware of these merits of the lawyer from Arras. On the other hand, virtually all people who know of Robespierre are convinced that he was a bloodthirsty monster. Why is that so? Because whenever the French Revolution is discussed, the majority of historians traditionally focus on the Terror, on the fact that, at the time of the “terror regime”, blood was spilled abundantly, and the accusing finger is pointed at Robespierre and his Jacobin confederates – and also to their Jacobin “ideology”. Let us take a closer look at the Terror, taking on the role of devil’s advocate on behalf of Robespierre.

Above all, the Terror must be understood in its historical context. In Ancien-Régime France, and in feudal Europe in general, terror and violence had already been used since time immemorial to achieve political objectives, more specifically, to maintain control over the denizens perched on the lower rungs of the societal ladder. Extremely functional in this sense were not only the bestial public executions, complete with endless tortures, but also the burning at the stake of witches, the bloody repression of heresies such as that of the Albigensians, and massacres like the infamous St. Bartholomew's Day in Paris in 1572.

In comparison with these “hot” or “savage” forms of terror, the “cold”, “disciplined” terror of the French Revolution may be described as rather humane. Torture, which was in fact formally abolished by the Revolution, was not involved anymore, and thanks to the guillotine, those condemned to death could “benefit” from a supposedly instant and painless death. Moreover, this type of execution, a decapitation, had earlier been a privilege reserved for the nobility, because ordinary folks were dispatched in other, much more horrible ways, such as (slow) hanging and quartering. On the other hand, during the Revolution, occasional lynchings of real or suspected counterrevolutionaries and of course the September massacres of 1792 echoed the “hot” terror of the Ancien Régime and reflected the brutalisation of the common people, provoked by the barbarous pre-revolutionary repressive practices. Gracchus Babeuf, an even more radical revolutionary than Robespierre, who would fall victim to the Thermidorian repression, aptly remarked in this context that

with their quarterings, tortures, breaking of bodies on the wheel, burnings at the stake, the whip, the gallows, the never-ending executions, our masters taught us these awful manners! Now they harvest what they themselves have sown. 6

The terror associated with Robespierre and his radical companions was unquestionably far less cruel and much more humane than the “hot” terror, not only of the Ancien Régime but also of the Revolution itself, and that was not fortuitous. With their “cold” terror, which was admittedly bloody, but disciplined, they wanted to prevent a repeat of the “hot”, bloody, and even bestial terror unleashed by the populace against the real or perceived enemies of the Revolution during the September massacres. “Let us be terrible so the people don’t have to be so”, was how things were clarified by one of Robespierre’s close associates, Danton.

Reflecting on the French Revolution, approximately one century after the fact, Mark Twain made the following insightful remark about “France and the French before the ever memorable and blessed Revolution, which swept a thousand years of . . . villainy away in one swift tidal wave of blood”:

There were two ‘reigns of Terror’ if we would but remember it and consider it: the one wrought murder in hot passion, the other in heartless cold blood; the one lasted mere months, the other had lasted a thousand years; the one inflicted death upon ten thousand persons, the other upon a hundred millions; but our shudders are all for the ‘horrors’ of the minor Terror, the momentary Terror, so to speak, whereas what is the horror of swift death by the ax [sic, meaning the guillotine] compared with life-long death from hunger, cold, insult, cruelty, and heart-break . . . all France could hardly contain the coffins filled by that older and real Terror – that unspeakably bitter and awful Terror which none of us has been taught to see in its vastness or pity as it deserves. 7

Second, a factor ought to be taken into account that is emphasized by the aforementioned American historian, Arno Mayer, in his book The Furies, which focuses on the bloodbaths of the French Revolution and of the Russian Revolution as well. One has to understand, he explains, that revolutionary terror is not unleashed because of a revolutionary ideology or of the bloodthirst of revolutionaries but emerges in specific historical circumstances and above all, when a revolution finds itself under great pressure from domestic and/or foreign enemies. Among the beleaguered revolutionaries, such a situation produces the (not unjustified) feeling that compromises are no longer possible, that either they themselves will perish, and the Revolution with them, or their enemies must be annihilated, and the counterrevolution with them. In other words, the Revolution ends up being convinced that it must kill in order to survive.

This certainly applies to the “hot” as well as “cold” terror witnessed by revolutionary France, especially in 1792-1793. At that time, the Revolution was threatened by foreign as well as domestic counterrevolutionaries. During the summer of 1792, things went from bad to worse in the war that had been unleashed so optimistically by the Girondins. Austrian troops penetrated into the country, and at the same time royalist uprisings erupted in the Vendée region. That sparked a kind of panic among the revolutionaries in the capital.

It is in this context that the Tuileries Palace was stormed by a mob consisting not only of Parisian sans-culottes but also contingents of volunteers that had arrived from cities such as Marseille; that the king’s Swiss Guards were massacred; and that the September Massacres took place. The situation improved remarkably after the French victory at Valmy on September 20, followed by other military successes, for example the “liberation” of the Austrian Netherlands, modern Belgium. That signified the end of the “hot” terror, whereas the “cold” terror had not started yet, even though executions were carried out, for example the high-profile dispatch of Louis XVI, found guilty – not without reason – of treason, after a proper trial.

In the spring of 1793, the counterrevolutionary spectre raised its fearsome head again at home as well as abroad. Insurrections in the Vendée, in Toulon, and elsewhere went hand in hand with military fiascos in the foreign wars; and Paris, the cradle of the Revolution, witnessed the spectacular assassination of a very popular revolutionary leader, Jean-Paul Marat. In the eyes of his traumatized revolutionary companions, this demonstrated that the Revolution was in mortal danger and could only be saved by drastic, merciless action against its domestic and foreign enemies. It was in those extremely critical circumstances that the Jacobin policy of repression, la Terreur, was launched.

It also deserves to be pointed out that ruthless measures did in fact contribute to save the Revolution. One of the draconian measures that were taken was the so-called “levée en masse”, that is, the induction into the army of massive numbers of men for the purpose of defending the fatherland. This made it possible to reverse the military tide in favour of the Revolution via victories against the domestic counterrevolution in the Vendée, in December 1793, and against the armies of the foreign counterrevolution in the battle of Fleurus, in June 1794.

The revolutionary terror, orchestrated by Robespierre and the Jacobins, was unquestionably horrible, but it should not be overlooked that the counterrevolution also made use of coercion, violence, and indeed terror to achieve its objectives. The counterrevolutionary terror revealed itself to be even more horrible than the revolutionary Terreur. Such, at least, is the opinion of Arno Mayer, the already mentioned expert in the field of the “furies”, that is, the violence used by all sides in the course of the French and Russian revolutions. He underscores the fact that, in both cases, the spilling of blood was not only the work of the Revolution, but also, and even more so, the work of the counterrevolution. “The furies of revolution”, explains Mayer, “are fueled primarily by the inevitable and unexceptional resistance of the forces and ideas opposed to it, at home and abroad”. 8

The revolutionary terror, orchestrated by Robespierre and the Jacobins, was unquestionably horrible, but it should not be overlooked that the counterrevolution also made use of coercion, violence, and indeed terror to achieve its objectives. The counterrevolutionary terror revealed itself to be even more horrible than the revolutionary Terreur. Such, at least, is the opinion of Arno Mayer, the already mentioned expert in the field of the “furies”, that is, the violence used by all sides in the course of the French and Russian revolutions. He underscores the fact that, in both cases, the spilling of blood was not only the work of the Revolution, but also, and even more so, the work of the counterrevolution. “The furies of revolution”, explains Mayer, “are fueled primarily by the inevitable and unexceptional resistance of the forces and ideas opposed to it, at home and abroad”. 8

Thermidor, for example, unleashed a “white terror”, an intrinsically “wild” or “hot” terror, in the style of the Ancien Régime. However, as conventional historiography generally reflects a critical and even hostile view of revolutions, it tends to pay little or no attention to counterrevolutionary excesses or at least to minimize their importance. Moreover, counterrevolutionary terror usually rages in the countryside and in provincial cities, so that, from a historiographical perspective, this “white terror” and its excesses are less “visible” and far less noticeable than the spectacular decapitations by means of the guillotine, the fearsome but photogenic “revolutionary razor” set up in the middle of a great square in the middle of the nation’s capital.

It should not be forgotten that it was at least thanks to the Terror that not just the radical Revolution of the Jacobins, but the entire Revolution, including its moderate, bourgeois incarnation, was saved from the claws of the domestic and foreign counterrevolution. Moreover, even though the Terreur was directed primarily against the “right-wing” enemies of the moderate as well as radical Revolution, in short, the counterrevolution, it also took on the “left-wing” opposition that existed within the revolutionaries’ own ranks. This was illustrated by the execution of Jacques Hébert, the head of a group of revolutionaries who were more radical than Robespierre and the Montagnard wing of the Jacobins; Hébert and his followers criticized Robespierre’s policy as overly moderate and pushed for even more radical reforms in favour of the sans-culottes. Robespierre’s guillotine took care of them just as efficiently as it took care of the counterrevolutionaries. With the weapon of the Terror, then, the radical revolution, essentially a petit-bourgeois phenomenon, also relieved the intrinsically grand-bourgeois revolution of the menace of an even more radical revolution. Despite this service, bourgeois historians have never expressed any gratitude to Robespierre and the Jacobins.

Finally, it is also instructive to compare the bloodbaths under Robespierre with the violence under the post-Thermidorian regimes, and more in particular under Napoleon. Of the terror blamed on Robespierre, linked with the radicalization and “internalization”, that is, the increasing democratization, of the French Revolution, it is estimated that it cost the lives of a total of 50,000 persons maximum, amounting to approximately 0.2 % of the country’s population at the time. (And these were certainly not all innocent victims, as is too often suggested, but bona fide enemies of the Revolution.) That is in fact very few, at least in comparison to the number of victims of the wars that accompanied the “externalization” of the Revolution and simultaneous suspension of the revolutionary democratization process, a suspension that, as we have seen, favoured the bourgeoisie and Napoleon’s antidemocratic, even dictatorial regime.

The Battle of Waterloo alone, the final stunt in the supposedly glorious career of Napoleon, caused the death or mutilation of 45,000 to 50,000 men; if we include that battle’s preliminary “skirmishes” at Ligny and Quatre Bras, we arrive at a total of between 80,000 and 90,000 dead and injured. The Battle of Leipzig, likewise lost by Napoleon, but in 1813, and today nearly forgotten, was responsible for 140,000 victims. And after his disastrous campaign in Russia, Bonaparte left behind many hundreds of thousands of dead and mutilated bodies. But nobody ever talks about a Napoleonic “terror”, and today Paris features countless monuments and sites that immortalize the supposedly heroic and brilliant achievements of the Corsican.

Also, should a comparison of the bloodbaths under Robespierre and Napoleon not take into account the undisputable fact that the guillotine brought a quick and painless death in comparison with death on the battlefield, where only the lucky ones were hit by a bullet in the chest and the wounded, usually horribly mutilated, were sometimes devoured by the wolves while still alive? By replacing permanent revolution in France, and especially in Paris, with permanent war all over Europe, remarked Marx and Engels, the Thermidorians and their successors “perfected” the Terror, in other words, made it far worse, caused much more blood to flow than was spilled under Robespierre’s Terreur.

Democracy – government not only by but also for the people – was the Revolution’s objective or, more accurately, the direction in which the Revolution was moving, And, as the Revolution became more radical, it produced more and more democracy. War, on the other hand, served the interests of the counterrevolution, it functioned to arrest and even reverse the progress towards democracy. And war was used by the bourgeoisie, a class that was not counterrevolutionary but opposed to revolutionary radicalism, to stop the revolutionary clock at a moment in time that was favorable to its class. Tragically, terror was an instrument used by all these actors to realize their objectives: terror may be used to advance democratization, but also to counter it.

The notion, widespread today, that Robespierre was a bloodthirsty monster and Napoleon a wonderful hero, does not reflect the historical reality; it is only a myth. Moreover, it is an extremely antidemocratic myth, because it demonizes the Revolution that created and favoured democracy in the sense that it launched the democratization process. Conversely, this myth glorifies war, the instrument par excellence of the counterrevolution, the archenemy of democratization. It is a nefarious myth because, on the one hand, it creates fear and repudiation of revolution among the popular masses, the “99 percent” who, today more than ever before, would benefit from the kind of democratization that achieves progress not exclusively but mainly via revolution, as we were able to learn from this brief survey of the history of the French Revolution. Conversely, this myth justifies and glorifies the wars that have too often functioned as counterrevolutionary and antidemocratic stratagems.

Historians such as François Furet in France, Ernst Nolte in Germany, and Simon Schama in Britain, like to bemoan the French Revolution on account of the violence and bloodshed associated with it, and they compare it unfavorably with the American Revolution, in their eyes a much more civilized historical phenomenon – sometimes eulogized as “a revolution without a revolution”! – and with the supposedly peaceful “evolution” towards modernity and democracy followed by Britain. Thanks to those historical developments, it is claimed, these two countries also managed to have the caterpillar of their Ancien Régime morph into the butterfly of a modern state, a supposedly democratic state that, like France, carries liberty, equality and justice in its banner.

As the great Italian historian Domenico Losurdo has explained in a brilliant opus, 9 the developments in the US and in Britain may only be described as peaceful if one ignores some primordial historical facts. Britain’s highly touted “evolution” towards democracy and other forms of “modernity” took centuries to come to fruition, because it started long before the French Revolution and obtained major successes, such as the introduction of universal suffrage, much later than France, namely only after the First World War — and, it deserves to be pointed out, after the Russian Revolution, without which universal suffrage would not have been introduced, as we will see in another chapter. This evolution was an extremely protracted affair, and the main reason for that was systematic and stubborn resistance, involving frequent use of violence unleashed from “above”, that is, from the British counterparts of the French counterrevolutionaries who, it must be added, have not yet been entirely vanquished. What comes to mind in this context are the civil wars of Cromwell’s time, massacres, similar to those in the Vendée, of Catholic “rebels” in the Irish and Scottish periphery, and of course the decapitation of a king, Charles I, in the centre of a square in the centre of the capital, not Paris, but London — and in the old-fashioned and inhumane way, with an axe.

As for the American Revolution, it was not a real revolution but essentially a rebellion, a revolt against the authorities in London by the colonial elite, an “English” patriciate of owners of plantations and plenty of slaves as well as wealthy merchants, (including slave traders), in other words, the US counterparts of France’s landowning aristocracy and haute bourgeoisie. 10 And this revolt received the indispensable armed support from the plebeian colonists, a kind of American version of the French sans-culottes.

This pseudo-revolution not only involved a full-fledged war against the British — in other words, the type of bloodshed for which historians generally do not show “red cards” — but also major massacres and mass deportations, whose victims were not only the numerous American colonists known as “Loyalists” because they remained loyal to the British Crown, but also the native population, the “Indians”. 11 Traditionally, massacres whose victims were Indians are also whitewashed by American historians, who prefer to euphemize them as “Indian Wars”. As mentioned, historians generally find wars to be legitimate and justifiable, and most of them tend to overlook crimes committed against dark-skinned folks.

In addition, by maintaining slavery — one of world history’s most spectacular forms of coercion and violence, in other words: terror – the American so-called revolution remained an unfinished symphony. A second revolutionary convulsion was required to finally bring about the formal abolition of slavery in the so-called “land of the free”, but crude and systematic discriminations victimizing Afro-Americans would continue to exist for a very long time. This second phase, known as the War of Secession or the American Civil War, lasted from 1861 to 1865. It amounted to a gigantic bloodbath, a Moloch more deadly for the country than the Second World War was to be. Yet in their zeal to present US history as peaceful in comparison to the French experience, historiographical illusionists such as Furet and Nolte ignore this terrible conflict and they pay little or no attention to the fate of the Indians and blacks. It is only in this questionable fashion that the myth of the dichotomy between a peaceful and sensible British and American evolution and a bloody, senseless French revolution can be kept alive.

While we are comparing the French Revolution to the American Revolution and the British “evolution”, it should also be noted that the French revolutionaries pursued equality for all Frenchmen and that they realized this objective, at least in the sense of formal equality before the law. Of the American and British cases, the same can only be said if one ignores entire historical chapters. In its original phase, the American Revolution achieved absolutely nothing positive for the Afro-Americans, who remained slaves, arguably under worse conditions than before. And the American Revolution was also a catastrophe for the indigenous population, the Indians; in the new state, they enjoyed no rights whatsoever but became the victims of a veritable genocide. According to a slogan that was to become popular in the new republic, “the only good Indian is a dead Indian”; and truly genocidal action followed these cynical words. This genocide provoked the admiration of Hitler and inspired his murderous plans with respect to Jews and other supposed “sub-humans” (Untermenschen). 12

To make it possible to favourably compare the historical developments in the US with the French Revolution, a supposedly gratuitously bloody affair, historians such as Furet have to avert their gaze from the millions — indeed: millions ! – of Indians who, in the course of the 18th and 19th centuries, were massacred by the Americans. As excuse for such negationism, one might perhaps cite the fact that, from a historiographic point of view, these bloodbaths were far less visible than the executions that took place in the public squares of major cities. Indeed, like the Thermidorian “white terror”, the massacres of Indians took place far from the urban centres, in isolated “rural” settings, namely the American version of the French countryside, the Far West. Did it come to the attention of a single denizen of New York or Boston, in December 1890, that a few thousand “Injuns”, including women and children and old folks, were massacred at Wounded Knee, a lost corner of faraway Dakota? Of this “Wild West”, as the Far West was also known, it may indeed be said that it was “wild”, not because it was inhabited by “savages”, because the Indians were not savages at all, but because it was the scene where the supposedly civilized American settlers unleashed against the indigenous population a truly “wild” terror, a terror that made the revolutionary as well as counterrevolutionary terror in France look like the work of clumsy amateurs.

The result of the French Revolution was an inclusive society, a homogeneous “nation” in which denizens previously treated as outsiders, Protestants and Jews, were henceforth members — citoyens, “citizens”— enjoying the same rights as Catholics. On the other hand, the result of the American Revolution was a “Herrenvolk 13 democracy”, that is, a society in which the advantages of liberty and equality were reserved for only a part of the population, the white citizens, while the two other parts, the Afro-Americans and the Native American, were denied the rights associated with citizenship. 14

The French Revolution integrated the minority that had been marginalized in the Ancien Régime; the American Revolution extegrated Blacks and Indians who, together, formed the majority of the population on the territory of the so-called “land of the free”. A similar phenomenon occurred in Britain, where the passage from the absolute monarchy to democracy and modernity was generally achieved to the benefit of the English population and to the detriment, not of all, but of a majority of the predominantly Catholic Irishmen and Scots, who were either massacred by the thousands in battles — or rather, butcheries — such as those of Drogheda and Culloden, or driven off their land to make room for English landlords and their sheep. 15

Executions, massacres, deportations, civil and international wars were thus not only a hallmark of the French Revolution, but also of more or less contemporary historical developments in the US and Britain. According to Arno Mayer, violence and bloodshed are inevitable whenever human history experiences a “new beginning”, revolutionary or not. The reason: the privileged of the old system always react with violence and bloodshed to any attempt to dislodge them from their towers of power and privilege.

In revolutionary circumstances, violence and terror also flare up because of numerous other factors that Mayer also mentions, for example the desire to take revenge for earlier injustices and — indeed ! — vulgar sadistic impulses on the side of the revolutionaries as well as counterrevolutionaries, because on both sides, the occasion makes not only the thief but also the sadist, the rapist, etc.

When one wants to evaluate a “rapid historical acceleration” of a turbulent, revolutionary nature, one will not get very far if one focuses mostly on the bloodshed that it involved — which is not to say that it is unimportant — but one must above all examine the results of these revolutions. (And it must be taken into account that not all movements that are called revolutionary are genuine revolutions.)