One of the most prominent intellectuals in the contemporary world was named to the list of the “Top 100 Global Thinkers” in Foreign Policy magazine in 2012.[1] He shares this distinction with the likes of Dick Cheney, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Benjamin Netanyahu, and former Mossad director Meir Dagan. The theorist’s best idea—according to this well-known publication that is a virtual arm of the U.S. State Department—is that “the big revolution the left is waiting for will never come.”[2]

Other ideas were surely strong contenders, and we could add to the list more recent positions. To select but a few examples, this top global thinker has described 20th-century communism, and more specifically Stalinism, as “maybe the worst ideological, political, ethical, social (and so on) catastrophe in the history of humanity.”[3] As a matter of fact, he adds for emphasis that “if you measure at some abstract level of suffering, Stalinism was worse than Nazism,” apparently regretting that the Red Army under Stalin defeated the Nazi war machine.[4] The Third Reich was not as “radical” in its violence as communism, he insists, and “the problem with Hitler was that he was not violent enough.”[5] Perhaps he could have taken some tips from Mao Zedong who, according to this theoretical grandee, made a “ruthless decision to starve tens of millions to death.”[6] This undocumented assertion positions its author well to the right of the anti-communist Black Book of Communism, which recognized that Mao did not intend to kill his compatriots.[7] Such information is of no import, however, to this theorist since he operates on the assumption that the worst ‘crime against humanity’ in the modern world was not Nazism or fascism, but rather communism.

The thinker in question is also a self-declared Eurocentric who intimates that Europe is politically, morally, and intellectually superior to all other regions of planet Earth.[8] When the European refugee crisis was intensified due to brutal Western military interventions around the wider Mediterranean region, he parroted Samuel Huntington’s ‘clash of civilizations’ credo by declaring that “it is a simple fact that most of the refugees come from a culture that is incompatible with Western European notions of human rights.”[9] This top-tier pundit also endorsed Donald Trump for president in the 2016 election.[10] More recently, he explicitly positioned himself to the right of the notorious warmonger Henry Kissinger by accusing the latter of “pacifism” and expressing his “full support” for the U.S. proxy war in the Ukraine, claiming that “we need a stronger NATO” to defend “European unity.”[11]

Being fêted by the preeminent journal co-founded by the arch-conservative national security state operative Huntington is only the tip of the iceberg for this global superstar, who has achieved a level of international fame rarely accorded to professional intellectuals.[12] In addition to being an academic celebrity with prestigious appointments at leading institutions in the capitalist world and innumerable international junkets, he has consolidated an enormous media platform. This includes publishing books and articles at a dizzying speed for some of the most prominent outlets, serving as the subject of multiple films, and regularly appearing on television and in major media spectacles.

Given the nature of these political positions and their amplification by the bourgeois cultural apparatus, one might assume that the thinker in question is a right-wing ideologue promoted by imperialist think tanks and the U.S. national security state. On the contrary, however, this is a commentator that anyone perusing online for radical theory or even Marxism is likely to encounter almost immediately, because he is one of the most visible intellectuals taken to represent the Left: Slavoj Žižek.

Donald Trump expressed his belief in the power of the U.S. propaganda machine by infamously claiming that he could “stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody” without losing a single voter.[13] In our perverse and decadent society of the spectacle within the imperialist core, much the same applies to the poster child for the global theory industry. Žižek could take the most reactionary political positions imaginable, have them broadcast around the world by the capitalist cultural apparatus, and still be presented as a towering intellectual of the Left. As a matter of fact, he has done precisely that.

Discursive Sausage for the Uneducated

As a young philosophy student in the United States in the early 1990s, I must admit that I was hoodwinked by this huckster and the system that promoted him. He burst onto the scene like the Evel Knievel of the theory industry when I was an undergraduate. Rather than endless disquisitions on a European philosophic history I knew nothing about, here was someone who could talk about it all to a poorly educated 19-year-old-wannabe intellectual: Hollywood movies, science fiction stories, consumer society, online culture, cool theories from Europe, pornography, sex, and, well, more sex. He was intoxicating to read, particularly for someone miseducated by the capitalist ideological apparatus and hungry for something—marketed as—different.

I devoured each book when it came out in the 1990s and early 21st century. I also followed on his heels by pursuing a Ph.D. under the direction of his intellectual father figure in Paris: Alain Badiou. However, as I continued to educate myself, I began to tire of his repetitions, theoretical superficiality, and rote rhetorical moves. I increasingly saw his provocative antics as a poor ersatz for historical and materialist analysis. This came to a head in 2001 when he endeavored to explain the events of September 11th through a cheeky Lacanian interpretation of The Matrix. His hot takes, while they sold like hot cakes, paled in comparison to rigorous materialist analyses of the history of U.S. imperialism and the machinations of its national security state, if it be in the work of Noam Chomsky, or much better, that of Michael Parenti.[14]

I then had a unique opportunity to see how Žižek’s discursive sausage is made when I translated a book by Jacques Rancière as a graduate student. Since Rancière was largely unknown in the Anglophone world at the time, every single publisher turned down the project. When I was finally able to talk one of them into considering it, after a hasty initial rejection, the acquisitions editor for the publishing house—which is now defunct—imposed one condition: to guarantee lucrative sales, I needed to secure a preface by a major marketing force in radical theory like Žižek. The latter agreed and later sent me a jumbled text that bore more than a striking resemblance to the section on Rancière in his book The Ticklish Subject.[15] He had added to this some free-associative ruminations and prefatory comments for one of Rancière’s books on cinema, which demonstrated little to no knowledge of the latter’s work on aesthetics or the book in question (I had translated Le Partage du sensible: Esthétique et politique). Disgusted by this shameless disregard for scholarly rigor, yet devoid of any institutional power or a deeper political analysis at the time, I felt that my hands were tied because I needed to accept the theory industry’s use of this charlatan to promote its commodities if I wanted my translation to see the light of day. I sought to bury the preface by turning it into a postface and surrounding it with scholarly elucidations of Rancière’s work. In retrospect, however, I should have simply halted the project.

In looking back on my experiences with the so-called Elvis of cultural theory, I now see that, as part of the ascendent and miseducated professional managerial class stratum in the imperialist core, I was the target audience for his antics. In 1989 the Berlin Wall fell, and Žižek’s first major book came out in English with Verso: The Sublime Object of Ideology. With a preface by the post-Marxist—viz. chichi anti-Marxist—radical democrat Ernesto Laclau, it was presented as a flagship publication in his new series with Chantal Mouffe. The series sought to draw on “anti-essentialist” theoretical trends, like those in France inspired by Martin Heidegger, in order to provide “a new vision for the Left conceived in terms of a radical and plural democracy” rather than support for socialism.[16] These two radical democrats—whose political orientation resonated with the anti-communist movements that were presented as ‘pro-democracy’ and used to dismantle socialist countries—played a central role in promoting Žižek. They invited him to present his work in the Anglophone world and opened up prestigious publication platforms to him. He reciprocated by explicitly using their post-Marxist pronunciamento, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy (1985), to frame his first book, based on their shared opposition to “the global solution-revolution” of “traditional Marxism.”[17] In 1991, the USSR was dismantled, and the aspiring post-Marxist theorist catering to the West published two more books: another in Laclau and Mouffe’s series, and one as an October book.[18] He thus definitively caught the rising theoretical wave of radical democracy just as dissident ‘pro-democracy’ movements backed by imperialist states and their intelligence services were aggressively rolling back the gains of the working class in order to redistribute wealth upwards.

As Soviet-style socialism was being dismantled, this Eastern European native informant increasingly presented his post-Marxism as nothing short of the most radical form of Marxism. Not unlike Elvis, who notoriously rose to fame in the music industry by appropriating, domesticating, and mainstreaming music from Black communities that was often rooted in very real struggles, Žižek became a front man in the global theory industry by borrowing his most important insights from the Marxist tradition but subjecting them to a playful postmodern cultural mash-up to crush their substance, thereby commodifying them for mass consumption in the neoliberal era of anti-communist revanchism. It is essential to note in this regard that, while the capitalist establishment celebrated the supposed end of history in the 1990s, it also promoted, for the rather niche social stratum of the radlib intelligentsia, the symbol of Marxism, purportedly set free from its substance, like a red balloon floating whichever way the—capitalist-driven—wind would blow. This was Žižek: he was to become the most well-known ‘Marxist’ in the neoliberal age of accelerated anti-communism. The mystery man from the East—a literal caricature of the ‘crazy Marxist,’ best captured by the sobriquet ‘the Borat of philosophy’—rose like a perverted phoenix publicly masturbating over the flames that had destroyed Soviet-style socialism.

Dialectical Sophistry

Like many of his fellow self-styled radical thinkers, whose snake oil sells so well because it is ever so slippery, Žižek prides himself on his elusive prose and erratic behavior. In reading him, one comes to anticipate, at the turn of each page, yet another ‘gotcha’ moment when we learn that it’s actually the opposite (of whatever he had led us to believe on the previous page)! Like a child who never tires of playing hide-and-seek, in spite of their inability to actually hide, the Slovenian wunderkind constantly shirks and spirals out of discursive control to say everything and its opposite in the hopes that he can cover his tracks and remain ever elusive. He appears to be ignorant of the fact that there is an obvious and consistent ideology operative in the chameleonic character of intellectuals of his ilk. It is called opportunism.

When Žižek was interviewed for the Abercrombie and Fitch catalog, his interviewer said she’d share the text with him in advance of publication. He retorted: “Oh that’s not necessary. Whatever I say, you can make me say the opposite!”[19] Saying something is just as good as saying its opposite for an opportunist whose main objective is to have his name in lights. In fact, if you say both over time—while disingenuously attributing this tiresome rhetorical move to ‘dialectics’ in order to provide pseudo-intellectual cover for nothing more than crass self-promotional chicanery—you occupy more space and take up even more time, squeezing out any of those who might actually have something to say. The fact that the bourgeois cultural apparatus gives him such an enormous platform reveals its proclivity to promote such tomfoolery over and against truly radical forms of analysis. It is worth recalling, in this regard, that his dada dialectics knows very precise limits. We have never heard him say, as far as I know, something like: ‘the dominant ideology constantly says that actually existing socialism was utterly horrific… but it’s precisely the opposite!’

[20]

Pro-Western, Anti-Communist Dissident

Since this grifter says and re-says just about everything and its opposite, it is helpful to focus on what he has actually done and the nature of his theoretical practice. To fully understand the latter, it is necessary to situate him and his specific skullduggery within the social relations of intellectual production. In other words, by theoretical practice, I not only mean his subjective activities as an intellectual but also the objective social totality within which he operates, and which has promoted him as an international superstar. Part of my argument is that Žižek needs to be understood as a cultural product of the global theory industry rather than fetishized as a sui generis subject.

The author of In Defense of Lost Causes was born in 1949, and he grew up in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY). He would later assert, with no evidence beyond anecdotes to support his claim, that “life in a Communist state was mostly worse than life in many capitalist states.”[21] However, his home country provided a quality of life for the masses that is worth briefly recalling:

Between 1960 and 1980 it [Yugoslavia] had one of the most vigorous growth rates, along with free medical care and education, a guaranteed right to an income, one-month vacation with pay, a literacy rate of over 90 per cent, and a life expectancy of seventy-two years. Yugoslavia also offered its multi-ethnic citizenry affordable public transportation, housing, and utilities, in a mostly publicly owned, market-socialist economy.[22]

According to his biographer Tony Myers, Žižek disliked the communist culture of his homeland. Surely clued into potential opportunities for personal socio-economic advancement in the larger capitalist world, this venal young intellectual devoted himself to imbibing Western pop culture. “As a student,” Myers writes, “he developed an interest in, and wrote about, French philosophy rather than the official communist paradigms of thought.”[23] His Master’s thesis on French theory “was deemed to be politically suspicious” because, in the words of his fellow Slovenian philosopher Mladen Dolar, “the authorities were concerned that the charismatic teaching of Žižek might improperly influence students with his dissident thinking.”[24]

He did end up writing his first book on the unrepentant Nazi Martin Heidegger, the principal reference for the Slovenian anti-communist opposition according to Žižek himself. He also published the first Slovene translation of the French philosopher who made an enormous contribution to rehabilitating Heidegger’s reputation after WWII: Jacques Derrida.[25] The French magus of deconstruction was himself directly involved in dissident anti-communist political activism against the government in Czechoslovakia.[26] He co-founded the French chapter of the Jan Hus Educational Foundation, which has been funded by an impressive array of corporate and Western governmental sources with a record of supporting anti-communist subversion, including the Margaret Thatcher Foundation, the Open Society Fund (Soros), the Ford Foundation, the United States Information Agency, and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), which is a CIA cutout.[27]

After a sojourn in Paris to complete a second Ph.D., Žižek returned to the SFRY in 1985 and first came to public attention as an anti-communist dissident who was part of the French-theory inflected, Western-oriented ‘opposition.’[28] “In [the] late 1980s,” he explained, “I myself was personally engaged in undermining the Yugoslav Socialist order.”[29] He was “the main political columnist” for Mladina, a prominent weekly publication that was part of the dissident movement against the communist government.[30] The magazine, for which he wrote a weekly column, was accused of being backed by the CIA in a long and detailed report by the Yugoslav Communist Party, which also highlighted the proliferation of counter-revolutionaries who were threatening the very survival of the SFRY.[31] Žižek later claimed, on numerous occasions, that this was precisely his orientation as a dissident who contributed to the fall of communism.[32] He was involved, amongst other things, in the Committee for the Protection of Human Rights of the Four Accused in 1988 that demanded, in his own words, “the abolishment of the existing socialist system” and “the global overthrow of the socialist regime.”[33] This was in perfect line with President Ronald Reagan’s National Security Decision Directive 133 (NSDD), which advocated in 1984 for “expanded efforts to promote a ‘quiet revolution’ to overthrow Communist governments and parties” in Yugoslavia and other Eastern European countries.[34]

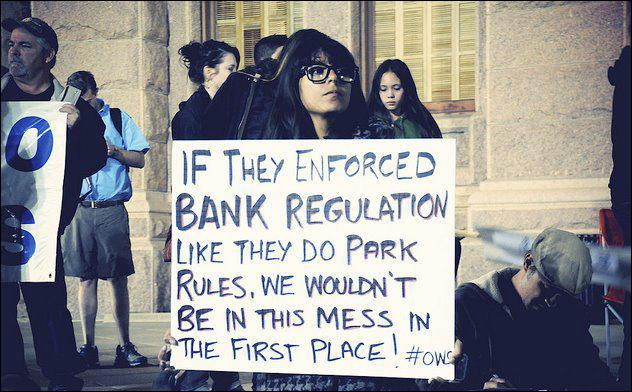

Žižek cofounded the Liberal Democratic Party (LDS), and he served as one of its leading public spokespeople.[35] The LDS was rooted in the liberal tradition of promoting ‘pluralism’ and would dominate Slovenia during the first decade after the end of socialism.[36] Žižek was the party’s candidate for the four-person presidency of the earliest break-away republic, which served as a wedge for dismantling the SFRY. He made the following campaign promise in a 1990 televised debate: “I can, as a member of the Presidency, substantially assist in the decomposition of ideologic Real-socialist apparatus of the state.”[37] He expressed his willingness to implement policies of liberal economic restructuring, which had already had catastrophic consequences for workers, asserting that he’s a “pragmatist” in this area: “if it works, why not try a dose of it?”[38] Indeed, he openly advocated for “planned privatizations” and flatly asserted, like a good capitalist ideologue: “more capitalism in our case would mean more social security.”[39] This was, once again, in perfect line with Reagan’s NSDD 133, which explicitly called for “Yugoslavia’s long-term internal liberalization” and the promotion of a “market-oriented Yugoslav economic structure.”[40]

The Eastern liberal also affirmed his support, at least in the short term of socialist demolition, for what the anti-communist philosopher Karl Popper called the ‘open society.’ He claimed that George Soros, the anti-communist founder of the Open Society Fund (and Popper’s former student), was “doing good work in the field of education, refugees and keeping the theoretical and social sciences spirit alive.”[41] Popper supported NATO’s intervention in the SFRY, and his work had been promoted by the Congress for Cultural Freedom, the infamous CIA front organization. Soros has been deeply invested in anti-socialist regime change operations in Eastern Europe. In Yugoslavia, “his Open Society Institute channeled more than $100m to the coffers of the anti-Milosevic opposition, funding political parties, publishing houses and ‘independent’ media.”[42] Moreover, Soros openly admitted that he was—through his foundation’s lavish funding of anti-communist organizations and activities—“profoundly implicated in the disintegration of the Soviet system.”[43]

Although Žižek was narrowly defeated in his presidential run, he served as the Ambassador for Science in the emerging post-socialist republic and apparently continues to provide informal advice to the government.[44] Indeed, he expressed his “open support for the Slovenian state after the restoration of capitalism in the 1990s,” and he remained faithful to his anti-communist liberalism: “I did something for which I lost almost all my friends, what no good leftist ever does: I fully supported the ruling party in Slovenia.”[45] The LDS, as a party of capital, pursued denationalization and privatization. This was in a context in which the IMF and World Bank were pushing through brutal economic counter-reforms that had been destroying the industrial sector, dismantling the welfare state, fostering the collapse of real wages, and laying off workers at a terrifying pace (614,000 out of a total industrial workforce of some 2.7 million had been laid off in 1989-90).[46] The pro-privatization party that Žižek openly supported, during a time of “massive declines of living standards for large sections of the world population,” was also keen on becoming a junior partner in the imperialist camp. It was “the leading proponent of accession to the European Union (EU) and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).”[47] This process began in the 1990s, and Slovenia officially joined the EU in 2003 and NATO the following year.[48]

It must not be lost on us, then, that this entrepreneurial intellectual had been for pro-Western civil society and against the state when the latter was socialist, whereas he was proudly against civil society and for the state when the latter turned capitalist (and sought membership in capitalist and imperialist transnational organizations).[49] As a matter of fact, in his presidential campaign, he advocated for an anti-socialist purge of the state apparatus, adding that he would be very strict and “start from scratch” regarding “the Administration of internal affairs, political police and so on.”[50] He explicitly advocated for developing an intelligence service that would be completely liquidated of all socialist elements, announcing what could only be interpreted as the CIA’s wet dream in the first break-away republic (which raises serious questions about his precise relationship to the agency that has played such a central role in overthrowing socialist governments around the world, often by working hand-in-glove with local anti-socialist political parties, intelligence agencies, publication outlets, and intellectuals): “There [regarding the Administration of internal affairs and the political police] I would make a cut. Now I will say something sinful. I think that in these turbulent times Slovenia will need an intelligence service because during this battle for sovereignty there will be actions to destabilize it. But for this service it is particularly important that it does not share any continuity with the current Administration of internal affairs [i.e. the socialist one]. Here I advocate a cut.”[51] The communists, according to this toady of the West, hate him. They undoubtedly recognize that he is an opportunist playing a very dangerous game to advance his career—as well as brutal privatization schemes and imperialist expansion—at the expense of the masses of workers. “I am rather perceived as some dark, ominous, plotting, political manipulator,” writes the Lacanian joker about how he’s seen in Slovenia, “a role I enjoy immensely and like very much.”[52]

[53] The Serbs, it is worth recalling, had “a proportionately higher percentage of Communist party membership than other nationalities.”[54]Žižek was thus parroting the position put forth by Ruder & Finn’s Director James Harff, who bragged that his spin doctors had been able to construct for the SFRY a “simple story of good guys and bad guys.”[55] The Eastern liberal even attempted to blame the communists, who had overseen a functioning multi-ethnic state for decades, for producing nationalism and “the compulsive attachment to the national Cause.”[56] He also embraced the Western demonization of the socialist President Slobodan Milošević by indulging in liberal horseshoe theory, claiming that “he managed to synthesize some unthinkable combination of fascism and Stalinism.”[57] However, whatever mistakes or misdeeds were committed by the socialists, the fact of the matter is that, as Michael Parenti has explained in a fact-driven book on the topic: “there was no civil war, no widespread killings, and no ethnic cleansing until the Western powers began to inject themselves into Yugoslavia’s internal affairs, financing the secessionist organizations and creating the politico-economic crisis that ignited the political strife.”[58]

Where did the pro-capitalist stand on NATO’s self-proclaimed humanitarian bombings of defenseless civilian populations and socialist infrastructure, whose real goal was the ‘Third Worldization’ and effective colonization of the only nation in the region that had refused to shed what remained of its socialism? He cheekily asserted, with his signature gusto for puerile provocation: “So, precisely as a Leftist, my answer to the dilemma ‘Bomb or not?’ is: not yet ENOUGH bombs, and they are TOO LATE.”[59] Since he made this ringing endorsement for intensifying the illegal mass murder of civilians in a draft that circulated online, and this particular statement dropped out of the text when it was published, we should note that he is crystal clear in other interviews, like when he flatly asserts: “I have always been in favor of military intervention from the West.”[60]

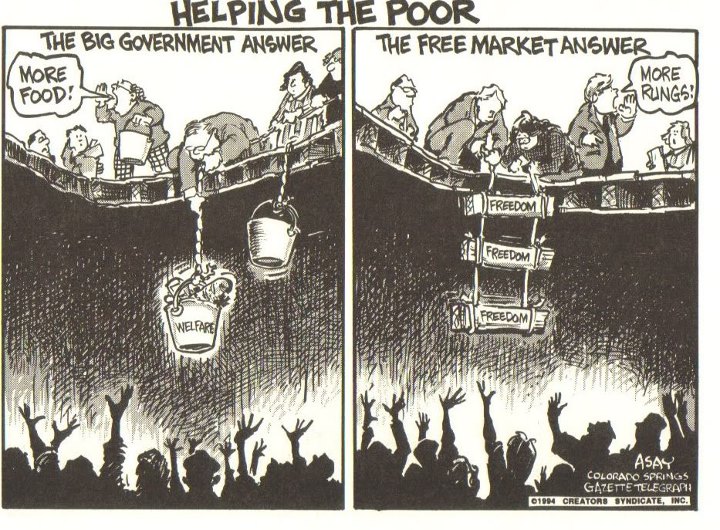

In his subsequent career as one of the world’s most visible public intellectuals, he has repeatedly taken strong positions against actually existing socialism. Cuba, for him, is nothing but “a nostalgic inert remainder of the past” that provides no hope for the future and is undeserving of even circumspect support.[61] In perfect line with capitalist propaganda, he casts China as an existential threat, and he unflinchingly describes Chinese communist leader Xi Jinping as an authoritarian capitalist who runs in the same corrupt gang as Trump, Putin, Modi, and Erdoğan.[62] It is quite obvious in reading him, in spite of his radical mummery, that he abides by Margret Thatcher’s infamous neoliberal mantra: TINA—There Is No Alternative. In fact, he regularly says as much himself: “I’m not aware of any convincing radical left alternatives” and “I don’t have any fundamental hopes in a socialist revolution or whatever.”[63] In the 1990 presidential debate mentioned above, he expressly embraced the views of Winston Churchill—whose dogged advocacy for colonial butchery positioned him “at the most brutal and brutish end of the British imperialist spectrum”—by claiming that capitalism “is the worst of all systems” but “we don’t have another one that would be better.”[64]

At the same time, he has regularly intervened in public debates to express his support for the European Union (a longstanding capitalist project promoted by the U.S. national security state as a bulwark against communism) and select acts of Western imperialism, including some of NATO’s brutal military interventions, particularly those in or near Europe.[65] His grand idea for the future of humanity is not to be found in the socialist states in the Global South that have waged successful anticolonial struggles against imperialism. It is instead located in the historic epicenter of colonialism and imperialism. “In today’s global capitalist world,” he writes, “it [the idea of Europe] offers the only model of a transnational organization having the authority to limit national sovereignty and the task of guaranteeing a minimum of norms for ecological and social well-being. Something subsists in this idea that directly descends from the best traditions of the European enlightenment.”[66] As a matter of fact, according to his Euro-diffusionist historical narrative, Third World anti-colonial struggles are themselves dependent upon concepts purportedly imported from the West, including what Žižek describes as the latter’s “self-critical examination” of its own “violence and exploitation” in the Third World.[67] As a social chauvinist who deeply believes that Europe is the natural leader of world development, he even concurs with Bruno Latour’s reactionary assertion that “only Europe can save us.”[68]

Commie Cosplay

In spite of Žižek’s clear political orientation in practice as a pro-Western anti-communist, who aggressively supported the overthrow of socialism in favor of capitalism, this self-styled eccentric never tires of claiming that he’s a communist. He even attempts to dress the part, so to speak, presenting himself as the ‘dirty communist’ from the East. In addition to the obligatory beard and the disheveled appearance, he belligerently talks over his interlocutors, spewing out endless dirtbag left provocation like pseudo-intellectual logorrhea was going out of style. A true performance to épater les bourgeois.

Žižek is neoliberal capitalism’s court jester. Aping the figure of the Marxist-qua-antisocial-fanatic, he encourages disdain for the real-world project of socialism, while hawking the wares of Western consumer society through his pop cultural mash-up. The histrionic show put on by this contumacious enfant terrible is—we must never forget—on the capitalist stage. The trickster is just a hireling, and a telling symptom of neoliberalism’s cultural apparatus. It is the capitalist court that has made the joker into a superstar, precisely because he has played his part so well. Like all good jesters, he pushes the limits of courtly decorum and says the most outrageous things in a hysterical spectacle of critique, while ultimately toeing the most important line by demonstrating his fealty to the puppet master (king capital).

To convincingly play his provocative part, this clown not only says he’s a Marxist, but he insists on being nothing short of a Leninist. Let’s listen in to one of his ridiculous rants, which, of course, is part of his routine and is therefore repeated in numerous texts: “I am a Leninist. Lenin wasn’t afraid to dirty his hands. […] When you get power, if you can, grab it. Do whatever is possible.”[69] This commie cosplay depiction amounts to saying that Leninism is all about playing dirty and ruthlessly pursuing power. Such a disingenuous representation of Lenin, and Marxism-Leninism more generally, is perfectly in line with a long ideological history. Benedetto Croce, the Italian liberal and fascist sympathizer, said the exact same thing about Marx: he was the Machiavelli of the proletariat because he put force first and sought to ruthlessly seize power.[70] Steve Bannon, relying on a similar conflation of Leninism with brute power politics, is also a self-declared “Leninist” à la Žižek.[71] This is likely one of the many reasons why the neo-Nazi leader Richard Spencer declared: “Slavoj Žižek is my favorite leftist. He has more to teach the alt Right than a million American conservative douches.”[72]

Since the jester always has more to say on every topic, let’s hear him out on what it means to be a Leninist in 2009, when he made the claim cited above: “I am a Leninist. […] This is why I supported Obama.”[73]This is one of his best jokes of all time. The deadpan delivery is killer because he actually means it. He literally equates Leninism with supporting the neoliberal Deporter-in-Chief whose diversity cred provided thin cover for revving the engine of the U.S. imperial machine around the world, leading to Obama’s infamous statement about his assassination program, namely that he was “really good at killing people.”[74] Žižek, though, homes in on the former President’s purportedly revolutionary approach to healthcare, meaning an imposed mandate for private insurance modeled on Republican Mitt Romney’s plan: “I think the battle he is fighting now over healthcare is extremely important, because it concerns the very core of the ruling ideology.”[75] Obama, we might remember, rejected any discussion whatsoever of single-payer healthcare, a system of universal coverage with socialist roots.

When you’re an idealist wag like Žižek, Leninism is just a word, a floating signifier, that you can play around with, using it as just one more prop or gimmick. This is painfully obvious in his comic book Repeating Lenin. In spite of what the straightforward title might suggest to the naïve and uninitiated, he proclaims: “I am careful to speak about not repeating Lenin. I am not an idiot. It wouldn’t mean anything to return to the Leninist working class party today.”[76] What he likes about Lenin “is precisely what scares people about him—the ruthless will to discard all prejudices. Why not violence? Horrible as it may sound, I think it’s a useful antidote to all the aseptic, frustrating, politically correct pacifism.”[77] It’s that unbridled death drive that the Slovenian Lacanian feels compelled to repeat. “To REPEAT Lenin,” he writes with clownish typography,“does NOT mean a RETURN to Lenin – to repeat Lenin is to accept that ‘Lenin is dead,’ that his particular solution failed, even failed monstrously, but that there was a utopian spark in it worth saving. […] To repeat Lenin is to repeat not what Lenin DID, but what he FAILED TO DO, his MISSED opportunities.”[78] As the most visible ‘Leninist’ never tires of repeating, communism was and is a cataclysmic failure. His compulsion to repeat it is thus best understood in terms of the line in Beckett that he regularly quotes in contexts such as these: “Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” What the future has in store, according to this rebel with a lost cause, is thus nothing more than enhanced failure: “we have to accept the fact that it is impossible for Communism to win […] , i.e., that, in this sense, Communism is a lost cause.”[79]

The final payoff for the jester’s commie cosplay is that the super-rich chortle in their martinis and invite him to write copy for their advertisements. Meanwhile, some students and members of the professional managerial class stratum buy up his pop philosophy thinking perhaps they’ll learn something about Marxism. Instead, they are taken on a theoretical magic carpet ride that demonstrates how ridiculous Marxism is while advertising Hollywood’s blockbuster films, TV shows, science fiction novels, and assorted consumer products of the global theory industry.

The Discreet Charm of the Petty-Bourgeoisie

Žižek, like Badiou, is not a historical materialist.[80] Neither of these philosophers engage in rigorous analysis of the concrete, material history of capitalism and the world socialist movement, and they eschew serious political economy in favor of discussing superstructural elements and products of the bourgeois cultural apparatus. Both of them openly indulge in an idealist philosophical approach that privileges ideas and discourses, and they are metaphysicians who defend an anti-scientific belief in superstition.

If we bracket their idiosyncratic vocabularies and examine their theoretical practices outside of the ideological confines of cultural commodity fetishism, their specific version of idealism could best be described as transcendental idealism. They present their brand-managed conceptual framework (largely based on personal interpretations of non-Marxist discourses like those of Jacques Lacan and G.W.F. Hegel) as the transcendental structure of reality. They then choose specific empirical elements—a current event, a text, a Hollywood movie, a candy wrapper, the back of a cereal box, a Starbucks’ cup, a porn site, or literally anything else, particularly in the case of Žižek—that they contend confirms this pre-established theoretical model, thereby producing the illusion that it has been proven true. Such a claim, however, can never be collectively tested in any rigorous manner, because it is up to the whims of each speculative prestidigitator to decide what empirical data corroborates their theoretical assumptions (and thus what information can be ignored).

This can be clearly seen in their approach to communism. Unlike Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, who maintained that “communism is the real movement which abolishes [aufhebt] the present state of things,” they assert that communism is an “Idea” and a “desire.”[81] At the same time, they regularly toe the capitalist propaganda line by condemning the real movement of communism for purportedly indulging in bloodthirsty terrorism, violent dictatorship, and genocide (blithely ignoring the need to provide documentation for such claims, or simply invoking as ‘proof’ the work of reactionary anti-communists or sources funded by the U.S. State Department and the Open Society Fund).[82] The possible exceptions they sometimes point to would often better be described as anarchist, at least as they interpret them, because they tend to celebrate moments of anti-state and anti-party insurgency, including against socialist states (as in Badiou’s interpretation of the Chinese Cultural Revolution).[83] Meanwhile, those who support actually existing socialism are presented as ideological dupes or remnants of a bygone era, trapped in an imaginary world not unlike those ensnared in capitalist ideology. “The left which aligned itself with ‘actually existing socialism’ has disappeared or turned into a historical curiosity” is what we are told in the introduction to their widely acclaimed volume The Idea of Communism.[84]

When this book was published by Verso in 2010, the Chinese Communist Party boasted some 80 million members, which surpassed the entire combined population of both France and Slovenia by about 16 million people. Where, then, we might wonder, are these social chauvinists getting their information about the current state of the world? The answer is embarrassingly simple for these idealist philosophers: Jacques Lacan and the Lacanian elements in Louis Althusser’s work. The latter drew on Lacan’s mirror stage and conceptualization of the imaginary to create a misleading portrayal of ideology in his famous interpellation scene.[85] As Althusser asserted in a passage that contradicts his earlier analysis, an individual becomes an ideological subject when it recognizes itself as the one being hailed (interpellé) by a police officer in the street, meaning that the individual identifies with the image put forth by the other, assuming one’s place in the extant symbolic order.

There is another possibility, however, which Lacan referred to in his seventh seminar as following the imperative to not compromise one’s desire (ne pas céder sur son désir), which Žižek has theorized in terms of the ‘ethical act.’ Rather than remaining an ideological subject trapped in an imagined relationship to the social relations of production within the symbolic order, one can become a Subject à la Badiou by fearlessly pursuing the Real, which is that je ne sais quoi that resists the symbolic order (while at the same time being “contained in the very symbolic form” insofar as the Real is “the absent Cause of the Symbolic”).[86] The object-cause of desire, what Lacan called the objet petit a, is in Žižek’s words “the void [of the Real] filled out by creative symbolic fiction.”[87] It drives our jouissance in the sense that we crave it precisely because of its impossibility: the Real can never be seamlessly integrated into the symbolic order or simply translated into what Lacan calls ‘reality.’[88]

[90] This is one of the reasons why Badiou peremptorily proclaims that “communist” cannot be used as an adjective to describe an actual party or state.[91] A century of collective aspirations and horrors has apparently demonstrated that “the Party-form, like that of the socialist-State, are henceforth inadequate for assuring the real support of the Idea.”[92] As a matter of fact, the communist Idea can only sustain politics that “it would be definitively absurd to say that they are communist.”[93] Anarchist would be the common term, and more specifically insurgent anarchism, merged with an unhealthy dose of metaphysics and utopian socialism. After all, this is a politics in which an individual becomes a Subject by being faithful to an inexplicable Event that interrupts history, acting on its consequences like the followers of Christ.

“Real communism” is thus a metaphysical communism of the Lacanian Real. Accordingly, we are told, the collective project of materially transforming the world is in fact destined to fail if it takes the form of parties or states since these would give concrete form or ‘symbolization’ to the otherworldly Real. Communism is thereby displaced from the realm of collective action aimed at socialist state-building projects—as a first but necessary step to break the chains of imperialism—to that of individual consciousness and the subjective experience of the privileged few that Nietzsche referred to as ‘free spirits.’ In counter-distinction to this small group of great thinkers and artists of the world, Žižek explains with his signature disdain for the working class, 99% of “concrete people” are “boring idiots.”[94] These hapless proles and peasants did not study in Paris with the petty-bourgeois luminaries of the global theory industry, so they have not understood what is most essential: communism is a subjective process of resisting the symbolic order of extant societies and desiring the impossible, even individually ‘acting on’ this desire.[95]

One of the reasons idealists love to heap scorn on materialists as somehow being crass reductionists and ‘unphilosophical,’ is precisely because the latter are capable of revealing the material structures that undergird and determine the conceptual games they play. If we subject the idealist communism of the Real to a class analysis, it becomes readily apparent that it rejects, under the heading of ‘actually existing socialism,’ the project of the masses, of the global Untermenschen (subhumans) who have imagined that they could make the Real of their desire into a historical reality. It is here that the Nietzschean orientation of these radical aristocrats comes clearly into view because they deride the purported ignorance of the hoi polloi. Over and against their crass materialism, the Real communists aspire to much more than the lowly pursuit of collective access to potable water, food, shelter, healthcare, and so on via concrete anti-imperialist state-building projects (all of these are in the realm of what Lacan called ‘need’ as opposed to ‘desire’). Real communists, in the Lacanian sense, have the supreme subjective dignity of individually demanding the impossible—not something that could materially help improve the lives of the global masses in the here-and-now.[96]

Such a posture literally means that these self-stylized radical thinkers demand something that cannot be done, which is the epitome of petty-bourgeois radicalism. What they truly desire, if we translate their pseudo-intellectual narcissistic self-indulgence into materialist terms, is the appearance of making the most radical demands imaginable while, at the same time, avoiding any threat to the material system of social hierarchies that has elevated them as leading intellectuals in the imperialist core. They desire the impossible, and even ‘act on’ this desire, precisely because they do not want anything to substantially change. That, then, is their big Idea of communism, namely that it is impossible.[97]

“The work of the Marxists,” wrote V.I. Lenin in a passage that anticipated the liberal leanings of the Lacanian-Althusserians, “is always ‘difficult’ but the thing that makes them different from the liberals is that they do not declare what is difficult to be impossible. The liberal calls difficult work impossible so as to conceal his renunciation of it.”[98] Marx also presciently described these capitalist accommodationists avant la lettrewhen he diagnosed the essence of petty-bourgeois sophistry in his critique of anarchism, which merges with liberal ideology on essential points. He traced its material roots back to opportunist careerism within the capitalist core. What he says here about Proudhon describes the idealist casuistry of Badiou and the ostentatious contradictions of Žižek with remarkable precision:

Proudhon had a natural inclination for dialectics. But as he never grasped really scientific dialectics he never got further than sophistry. This is in fact connected with his petty-bourgeois point of view. Like the historian Raumer, the petty bourgeois is made up of on-the-one-hand and on-the-other-hand. This is so in his economic interests and therefore in his politics, religious, scientific and artistic views. And likewise in his morals, IN EVERYTHING. He is a living contradiction. If, like Proudhon, he is in addition an ingenious man, he will soon learn to play with his own contradictions and develop them according to circumstances into striking, ostentatious, now scandalous now brilliant paradoxes. Charlatanism in science and accommodation in politics are inseparable from such a point of view. There remains only one governing motive, the vanity of the subject, and the only question for him, as for all vain people, is the success of the moment, the éclat of the day. Thus the simple moral sense, which always kept a Rousseau, for instance, from even the semblance of compromise with the powers that be, is bound to disappear.[99]

Radical Recuperator

The collapsing biosphere, the rise of fascism, and the threat of the ‘new’ Cold War turning into WWIII all mean that the stakes of contemporary class struggle could not be higher. Capitalism’s court jester, like other intellectuals of his ilk, is applauded by the ruling class’s elite managers and promoted internationally for encouraging us to ride fearlessly into the apocalypse of ‘the Real’ while lapping up his provocative hot takes and binge-watching the blockbuster films and TV shows he promotes.

This neoliberal prankster is thus the epitome of a radical recuperator. He cultivates and markets the appearance of radicality in order to recuperate potentially radical elements in society, particularly young people and students, within the pro-imperialist anti-communist fold. This is precisely why he is the most famous ‘Marxist’ in the capitalist world, festooned by the likes of a journal linked to the engine of U.S. imperialism. His mantra is nothing but an opportunistic perversion of the closing lines of The Communist Manifesto: “Cultural consumers of the pro-Western world unite—and buy my next book, or movie, or crossover product, or whatever, and so on, and so on!”

Notes.

[1] I would like to express my gratitude to Jennifer Ponce de León, Eduardo Rodríguez and Marcela Romero Rivera for encouraging me to write this article and providing feedback on it, along with Helmut-Harry Loewen and Julian Sempill. I accept full responsibility, however, for any errors or infelicities.

https://web.archive.org/web/20121201034713/http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2012/11/26/the_fp_100_global_thinkers?page=0,55#thinker92> (accessed on November 22, 2022).

[4] Ibid. Also see Slavoj Žižek. Did Somebody Say Totalitarianism? Five Interventions in the (Mis)use of a Notion (London: Verso, 2001), 127-129.

[5] Slavoj Žižek, In Defense of Lost Causes (London: Verso, 2009), 151 (Žižek’s emphasis).

[6] Ibid. 169.

[7] See Domenico Losurdo’s insightful critique of Žižek in Western Marxism. Trans. Steven Colatrella (New York: 1804 Books, forthcoming).

[12] Huntington served as White House Coordinator of Security Planning for the National Security Council. He also worked as an adviser to P.W. Botha’s Security Services in Apartheid South Africa (Botha was an outspoken opponent of Black political power and international communism, as well as an unrepentant defender of Apartheid).

[14] See, for instance, Noam Chomsky. 9/11: Was There an Alternative? (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2001) and Michael Parenti. The Terrorism Trap: September 11 and Beyond (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2002).

[17] Žižek, The Sublime Object of Ideology, 6 (on Žižek’s embrace of their theoretical matrix, see his acknowledgements on page xvi). I also refer the reader to the book Žižek and Laclau wrote with fellow ‘anti-totalitarian’ radical democrat Judith Butler for the “Phronesis” series. In their co-authored introduction, they present the book as being founded on Hegemony and Socialist Strategy insofar as it “represented a turn to poststructuralist theory within Marxism, one that took the problem of language to be essential to the formulation of an anti-totalitarian, radical democratic project” (Contingency, Hegemony, Universality: Contemporary Dialogues on the Left. London: Verso, 2000, 1, my emphasis).

[18] Žižek described his second book for the series “Phronesis” as being based on a series of lectures in Slovenia “aimed at the ‘benevolently neutral’ public of intellectuals who were the moving force of the drive for democracy” (For They Know Not What They Do: Enjoyment as a Political Factor. London: Verso, 1991, 3). In addition to Laclau and Mouffe, the Lacanian Joan Copjec helped facilitate the rise of Žižek in the Anglophone world through her promotion of his work in the circles of the French-theory driven New York City arts journal October. As he points out in the acknowledgments to his 1991 book Looking Awry, published as an October book with MIT Press, Copjec “was present from the very conception” of the project, encouraged him to write it, and spent time helping him with the manuscript (Looking Awry: An Introduction to Jacques Lacan through Popular Culture. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1991, xi).

[19] Jodi Dean. Žižek’s Politics (New York: Routledge, 2006), xi.

[22] Michael Parenti. To Kill a Nation: The Attack on Yugoslavia (London: Verso, 2000), 17. Drawing on World Bank data, which could not be suspected of pro-socialist sympathies, Michel Chossudovsky provides a similar portrait of pre-1980 Yugoslavia in The Globalization of Poverty and the New World Order (Pincourt, Canada: Global Research, 2003), 259.

[23] Tony Myers. Slavoj Žižek (New York: Routledge, 2003), 10.

[24] Ibid. 7.

[25] On the Heideggerian ‘opposition’ and Žižek’s first book, see Christopher Hanlon and Slavoj Žižek. “Psychoanalysis and the Post-Political: An Interview with Slavoj Žižek.” New Literary History 32:1 (Winter, 2001): 1-21.

[26] See, for instance, Barbara Day. The Velvet Philosophers (London: The Claridge Press, 1999).

[27] On the NED, see William Blum. Rogue State: A Guide to the World’s Only Superpower (London: Zed Books, 2014), 238-243. Allen Weinstein, who helped draft the legislation establishing the NED, openly acknowledged that “a lot of what we do today was done covertly 25 years ago by the CIA” (ibid. 239).

[30] Ernesto Laclau. “Preface.” Žižek, The Sublime Object of Ideology, xi.

> (accessed on November 22, 2022).

[33] Žižek, “A Leftist Plea for ‘Eurocentrism,’” 990.

[34] Cited in F. William Engdahl. Manifest Destiny: Democracy as Cognitive Dissonance (Wiesbaden: mine.Books, 2018), 101.

[36] See, for instance, “Lacan in Slovenia: An Interview with Slavoj Žižek and Renata Salecl.” Radical Philosophy 58 (Summer 1991). It would be interesting to explore the history of this party’s financing, following the lead of the great Michael Parenti’s analysis of the dismantling of Yugoslavia: “US leaders—using the National Endowment for Democracy, various CIA fronts, and other agencies—funneled campaign money and advice to conservative separatist political groups, described in the US media as ‘pro-West’ and the ‘democratic opposition’” (To Kill a Nation, 26).

[38] “Lacan in Slovenia,” 30.

https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/ctheory/article/view/14649/5529> (accessed on November 22, 2022).

[43] Cited in Néstor Kohan. Hegemonía y cultura en tiempos de contrainsurgencia “soft” (Ocean Sur, 2021), 63.

[44] See Myers, Slavoj Žižek, 9.

[45] Lovink, “Civil Society, Fanaticism, and Digital Reality.”

[46] See, for instance, Chossudovsky, The Globalization of Poverty, 267: “Croatia, Slovenia and Macedonia had agreed to loan packages to pay off their shares of the Yugoslav debt […]. The all too familiar pattern of plant closings, induced bank failures, and impoverishment has continued unabated since 1996 [i.e. in the wake of the November 1995 Dayton Accords]. And who was to carry out IMF diktats? The leaders of the newly sovereign states have fully collaborated with the creditors.”

[48] See Matjaž Klemenčič and Mitja Žagar. The Former Yugoslavia’s Diverse Peoples (Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, Inc., 2004), 300-301.

[49] See, for instance, Lovink, “Civil Society, Fanaticism, and Digital Reality.”

[51] Ibid.

[52] Lovink, “Civil Society, Fanaticism, and Digital Reality.”

[54] Parenti, To Kill a Nation, 81.

[55] Quoted in ibid. 92.

[56] Slavoj Žižek. “Eastern Europe’s Republics of Gilead.” New Left Review I/183 (Sept/Oct 1990): 58.

[57] Žižek, “Lacan in Slovenia,” 29. Milošević reportedly launched his campaign of ‘ethnic cleansing’ against Kosovo in a speech he gave in 1989. As reported by Michael Parenti, who provides essential contextualization that contradicts, on numerous points, Žižek’s hot takes, here is part of what Milošević said: “Citizens of different nationalities, religions, and races have been living together more and more frequently and more and more successfully. Socialism in particular, being a progressive and just democratic society, should not allow people to be divided in the national and religious respect” (To Kill a Nation, 188).

[58] Žižek, “NATO, the Left Hand of God.”

[59] Cited in Parker, Slavoj Žižek, 35.

[60] Lovink, “Civil Society, Fanaticism, and Digital Reality.”

https://zizek.uk/slavoj-zizek-on-cuba-and-yugoslavia/> (accessed on November 22, 2022). Also see Žižek, “The Communist Desire.”

[62] Žižek, “Nous pouvons encore être fiers de l’Europe!”

[63] See his interview on the British BBC show “HARDtalk,” cited above, and Lovink, “Civil Society, Fanaticism, and Digital Reality.”

[66] Žižek, “Nous pouvons encore être fiers de l’Europe!”

[67] Slavoj Žižek. First as Tragedy, then as Farce (London: Verso, 2009), 115.

[68] Žižek, “Nous pouvons encore être fiers de l’Europe!”

[70] See, for instance, Domenico Losurdo’s insightful critiques of Croce in Antonio Gramsci: Del liberalismo al comunismo crítico(Madrid: disenso, 1997).

[73] Slavoj Žižek. “New Statesman Interview.”

[75] Žižek, “New Statesman Interview.”

https://nosubject.com/I_am_a_fighting_atheist> (accessed on November 22, 2022).

[77] Ibid.

[78] Slavoj Žižek. Repeating Lenin (Zagreb: bastard books, 2001), 137.

[79] Žižek, “The Communist Desire.”

[80] To take but one example among many others, Žižek has the audacity to claim that class struggle is not part of “objective social reality” but is instead the Real “in the strict Lacanian sense,” meaning that class struggle “is none other than the name for the unfathomable limit that cannot be objectivized, located within the social totality” (Slavoj Žižek, Ed. Mapping Ideology. London: Verso, 2000, 25, 22).

[81] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Collected Works. Vol. 5 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1976), 49.

[83] For an excellent critique of Badiou along these lines, see Losurdo, Western Marxism.

[84] Costas Douzinas and Slavoj Žižek, Eds. The Idea of Communism (London: Verso Books, 2010), viii.

[85] See Gabriel Rockhill and Jennifer Ponce de León. “Toward a Compositional Model of Ideology: Materialism, Aesthetics and Social Imaginaries.” Philosophy Today 64:1 (winter 2020).

[87] Ibid. 76.

[88] Žižek, Looking Awry, 12. I am under no illusion regarding the stability of Žižek’s political positions or, for that matter, his interpretation of Lacan or other issues. As an opportunist, he has, of course, taken numerous different positions, some of which show clear signs of self-contradiction. What I am pointing out here, then, is simply one of the more coherent through-lines in his work, namely the theme of the ethical act, as it segues with Badiou’s theory of the subject.

[89] Alain Badiou. L’hypothèse communiste (Paris: Nouvelles Éditions Lignes, 2009), 189. On numerous occasions, Žižek explicitly embraces Badiou’s Idea of communism, which overlaps with the former’s extensive writings on the ethical act. Here is one example: “The communist Idea thus persists: it survives the failures of its realization as a specter which returns again and again, in an endless persistence best recapitulated by Beckett’s already-quoted words: ‘Try again. Fail again. Fail better’” (Douzinas and Žižek, Eds., The Idea of Communism, 217).

[90] Badiou, L’hypothèse communiste, 188.

[91] Ibid. 189.

[92] Ibid. 202. Never to be outdone in the realm of hyperbole, Žižek doubles down on Badiou’s position and takes it even further: “If it is to survive, the radical left should thus rethink the basic premises of its activity. We should dismiss not only the two main forms of twentieth century state socialism (the social-democratic welfare state and the Stalinist party dictatorship) but also the very standard by means of which the radical left usually measures the failure of the first two: the libertarian vision of communism as association, multitude, councils, anti-representationist direct democracy based on citizens’ permanent engagement” (Taek-Gwang Lee and Slavoj Žižek. The Idea of Communism. Vol 3. The Seoul Conference. London: Verso, 2016).

[93] Badiou, L’hypothèse communiste, 190. Badiou tellingly references the following examples: “the

Solidarność movement in Poland in the years 1980-81, the first sequence of the Iranian Revolution, the Political Organization in France [Badiou’s political group], the Zapatista movement in Mexico, the Maoists in Nepal” (ibid. 203). In the third volume of The Idea of Communism, which was based on a conference in South Korea—a capitalist state and de facto U.S. colony occupied by the military—Badiou insists in his opening comments that the participants in the conference “have nothing to do with the nationalist and military state of North Korea,” adding for good measure: “We have, more generally, nothing to do with the communist parties that here and there continue the old fashion of the last century [i.e. actually existing socialism].”

[95] Žižek has written extensively on Antigone as someone who performed just such an act by rebelling against the state and rejecting the reign of the ‘reality principle’ in favor of an uncompromising dedication to her desire (to bury her brother and thus honor the higher law of the gods). “An act is not only a gesture that ‘does the impossible,’” he contends in his glorification of individual desire à la Antigone, “but an intervention in social reality which changes the very coordinates of what is perceived as ‘possible’” (Did Somebody Say Totalitarianism?, 167).

[96] Badiou and Žižek have occasionally taken political positions in support of the working class, and this is not the object of my critique. It is instead their stalwart opposition—with only very minor and explainable exceptions—to the international socialist movement from 1917 to the present, which has taken the form of anti-imperialist state building projects from the USSR to Vietnam, China, Cuba and beyond.

[97] See Radhika Desai. “The New Communists of the Commons: Twenty-First-Century Proudhonists.” International Critical Thought1:2 (August 1, 2011): 204-223.

[98] V.I. Lenin. Collected Works. Vol. 19 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1977), 396.

[99] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Collected Works. Vol. 20 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1976), 33.

By Billy Bob

By Billy Bob

Billy Bob is a dedicated anti-imperialist activist and blogger. He hosts the Blowback roundatable. You can reach him at his Facebook page HERE.

Billy Bob is a dedicated anti-imperialist activist and blogger. He hosts the Blowback roundatable. You can reach him at his Facebook page HERE.  Billy Bob is a dedicated anti-imperialist activist and blogger. He hosts the Blowback roundatable. You can reach him at his Facebook page HERE.

Billy Bob is a dedicated anti-imperialist activist and blogger. He hosts the Blowback roundatable. You can reach him at his Facebook page HERE.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License