By Chris Gilbert and Vilma Kahlo, MRZine

The Washington mafia has always gone after guerrillas with the zeal of a fanatical exterminator. Never mind that the guerrillas represent the interests of the poor.

If regular armies are generally a man’s world, guerrillas and insurgent forces are just the contrary. There women have always had a central role. Think of Agustina of Aragon, Olga Benário, Tania Bunke, Maria Grajales, and Celia Sánchez, or even (stretching a bit) the legendary Amazons. It is not for nothing that Liberté — the allegorical figure depicted by Delacroix in the barricades of the July Revolution — is a woman.

Colombia is no exception to this rule. From even before the independence, women such as the Cacica Gaitana and Policarpa Salavarrieta have had a key role in armed struggle. Today this legacy of women in resistance continues in Colombia’s FARC-EP (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, People’s Army), which is the world’s longest-lasting guerrilla still in operation. This seasoned political and military organization, now engaged in peace dialogs in Havana, has sent a delegation there that is about a third women.

Who are these women? What makes them risk their lives for the ideals of socialism and national liberation in a country that is heavily dominated by the U.S.? What is their role in the current peace process, which aims at a negotiated solution to Colombia’s 50-year-old internal conflict? As a result of our visits to the peace delegation in Havana during the past months, we have come back with interesting answers to these and other questions about women in the Colombian insurgency.

Poverty and Injustice

That Colombia’s society is characterized by extreme inequality (with a Gini index as high as .89 in some areas) is well known. Yet, like poverty worldwide, its burden is born especially by women. A combatant named Marcela González referred to the link between gender, poverty, and oppression: “Women have the worst lot in this conflict. . . Most displaced people are women. Added to this is the sexual violence, family violence, and the fact that most [displaced people] are heads of families and wander with their children around the national territory. It is a human tragedy that women live in Colombia.”

Though women certainly have it worse in Colombia, making up a large part of the nation’s almost five million displaced people, the principal reasons men and women enter the guerrilla are just the same. These are basically poverty, injustice, and the inability to do legal political opposition from the left. “The indigence and poverty,” Marcela continued, “obliges people to look for a way out of that reality.”

The lack of political options is really key in determining how struggle takes shape. The last serious attempt to constitute a legal alternative party was the Unión Patriótica, formed in 1985. It generated widespread enthusiasm. However, agents of the oligarchy massacred the U.P.’s militants to the tune of about 5,000 deaths in less than a decade. The historical lesson, written on the walls with the blood of the political opposition, is that one has to fight for democracy where it doesn’t exist. For now, it is only possible to question Colombia’s oligarchical regime — armed to the teeth by the U.S and its allies — bearing arms oneself.

Once in the guerrilla, men and women take on all the same tasks. “Men and women have the same rights and the same responsibilities,” explained Bibiana Hernández, who has been in the guerrilla some thirty years. “In the same way as we tote wood and other supplies and organize the mass movement, so we also go to combat and face the enemy. We’re in the same conditions as men.” Women also assume roles of direction and leadership in the FARC-EP, and their equality is part of the statutes of the organization.

The women in the current peace delegation come from highly varied backgrounds. Camila Cienfuegos was born in a family from the countryside and saw extreme poverty with her own eyes as a youngster. Laura Villa got a medical degree in Bogotá. She mentions privatizations in education and health services as weighing in her decision to join the FARC’s revolutionary struggle, where she now contributes her medical expertise. Alexandra Nariño, born Tanja Nijmeijer in Holland, found a job teaching English in Colombia in 1998. Then a gradual process of learning about the oppression and political injustice in the country led to her entering the guerrilla.

These women are continuing an old tradition in the FARC. The organization was founded in 1964, when 48 peasant farmers inMarquetalia successfully withstood the attack of more than 10,000 government troops. Among the “Marquetalianos” were two heroic young women: Judith Grisales and Miriam Narváez.

Away from the War

The dozen or so women members of the FARC’s delegation may be survivors of a brutal conflict — one of the dirty not-so-little wars of the U.S. — but their soft-spoken manners and civilian clothes tend to make you forget about war. You can sit down with them at the historic Coppelia for an ice cream or join them in browsing used books in Havana’s innumerablebookstores. Despite their political tasks, there is still time for reading. Diana Grajales, a guerrillera from southwest Colombia, told us that she is immersing herself in the books of Che Guevara.

One of these women’s current projects — in addition to “rearming” with books and participating in the peace conversations with government delegates — is to make contact with women’s organizations. “We are listening to the proposals of Colombian women’s organizations that come to us,” Alexandra explained, adding that the contacts are also with international women’s groups. Comandante Yira Castroobserved that women’s movements are often made invisible, but the peace process has allowed the guerrilleras in the delegation to learn more about other women’s struggles and share experiences with them. They also maintain a Web page and Facebook account.

Despite the unbroken tranquility of Havana, the war comes back in surprising ways when you are in the company of the delegation. Seeing a scar on an exposed arm or noticing the limp of a compañera serves as a reminder of how Colombia’s government has systematically violated human rights during the war. Colombia’s is an unequal, imperial conflict in which — like those in Vietnam or Algeria — no holds are barred to maintain the neocolonial order. Many of these women have survived high-tech bombings that resemble the U.S. and Israel’s “surgical” assassination attempts. Some have lost close friends and family members, killed in cold blood or disappeared into mass graves like the Macarena, the largest mass grave in Latin America, where Colombia’s special forces depositedsome 2,000 corpses. At least one member of the delegation has been a victim of torture and rape by enemy soldiers.

Laura Villa spoke of the harsh realities of war: “A war is a war. This is a war for the liberation of the people, and in it there are deaths and wounded. There are casualties that affect us very deeply.” Among the painfully felt losses is that of Comandante Alfonso Cano, who initiated the current peace process but was murdered by the army two years ago. “The historical record is full of military people who abuse power and are guilty of disappearing people,” said Camila Cienfuegos. “Think of the mothers ofSoacha, whose children were presented as false positives [assassinated and then dressed as guerrilla fighters]. That is . . . state terrorism.” Camila speaks from experience about state terror: she has cigarette burns on her hands and arms from being tortured during an interrogation by the Colombian army.

On top of the human rights violations, there is nonstop defamation of the FARC’s women combatants by Colombia’s mass media. They invent stories about guerrilleras that are simply a projection of the society outside — a society that, because it pressures women to enter into all kinds of exploitative relationships in work and private life, sometimes accepts the mistaken and malicious idea that women are forced to enter the FARC. Or again, the commercial media falsely accuses guerrilleras, who enjoy conditions of gender equality in the FARC that are far superior to those in the society outside, of being merely the cooks and sexual partners of the comandantes.

Looking Toward Peace

One reason for this kind of defamation is to try to divide and conquer the FARC-EP, separating women from men. The effort is futile, say the women of the delegation. In fact, it does not deter a growing number of women from making the decision to change the world rather than simply contemplate it — to use Laura Villa’s description of her own motives for entering the guerrilla — nor does it cause the women already in the FARC to alter their basic vision of social problems or abandon a struggle that they understand to be essentially about class and social justice.

This last point is important. The women in the FARC see patriarchal domination as part of class struggle and are unwilling to separate the two, as some feminists have fallen into the error of doing. They fight not just for Colombian women but for Colombia as a whole. By the same token the peace they might make — a peace with social justice, a peace which goes to the roots of the conflict in social inequality — would also be a peace for the whole society.

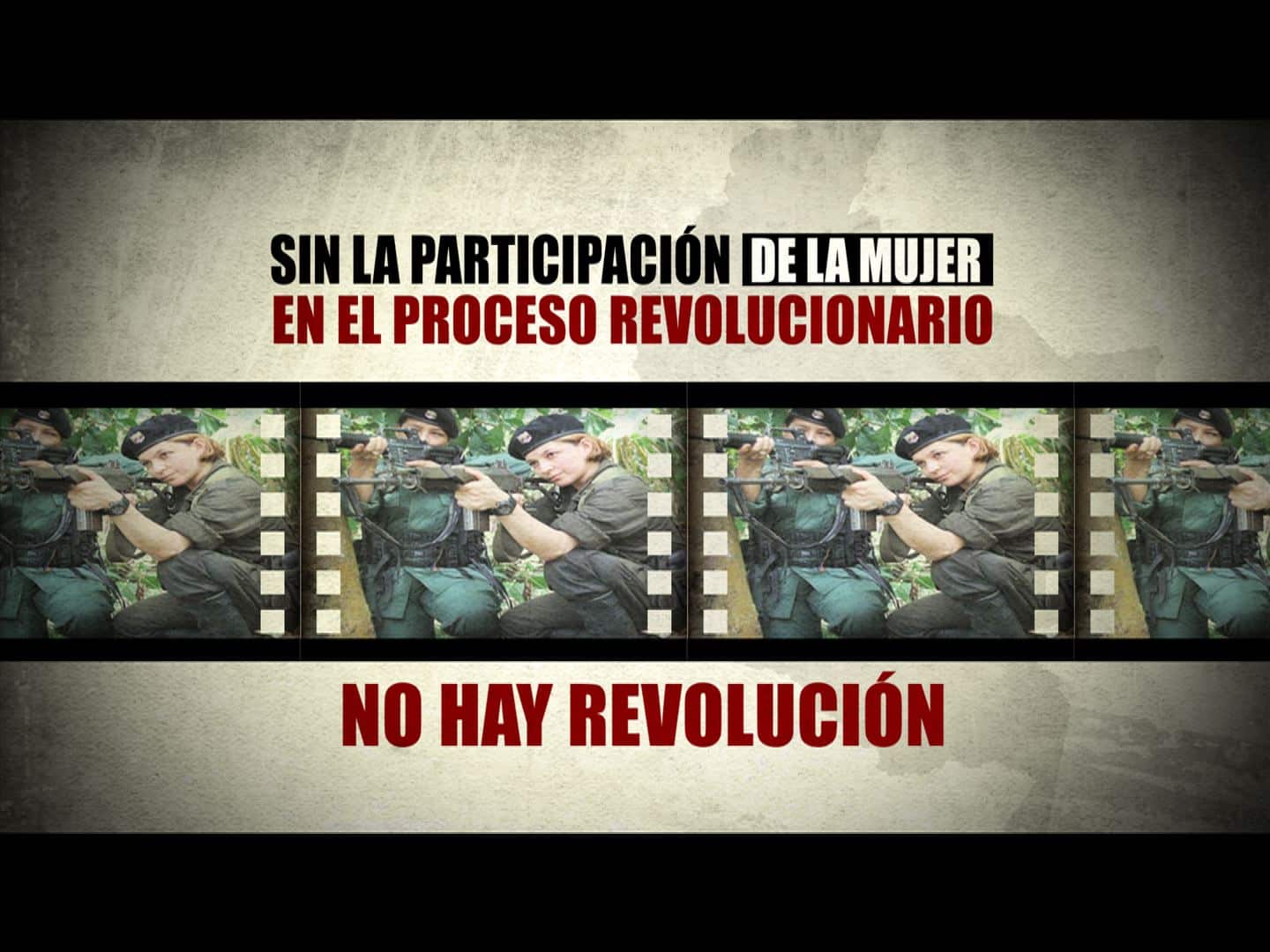

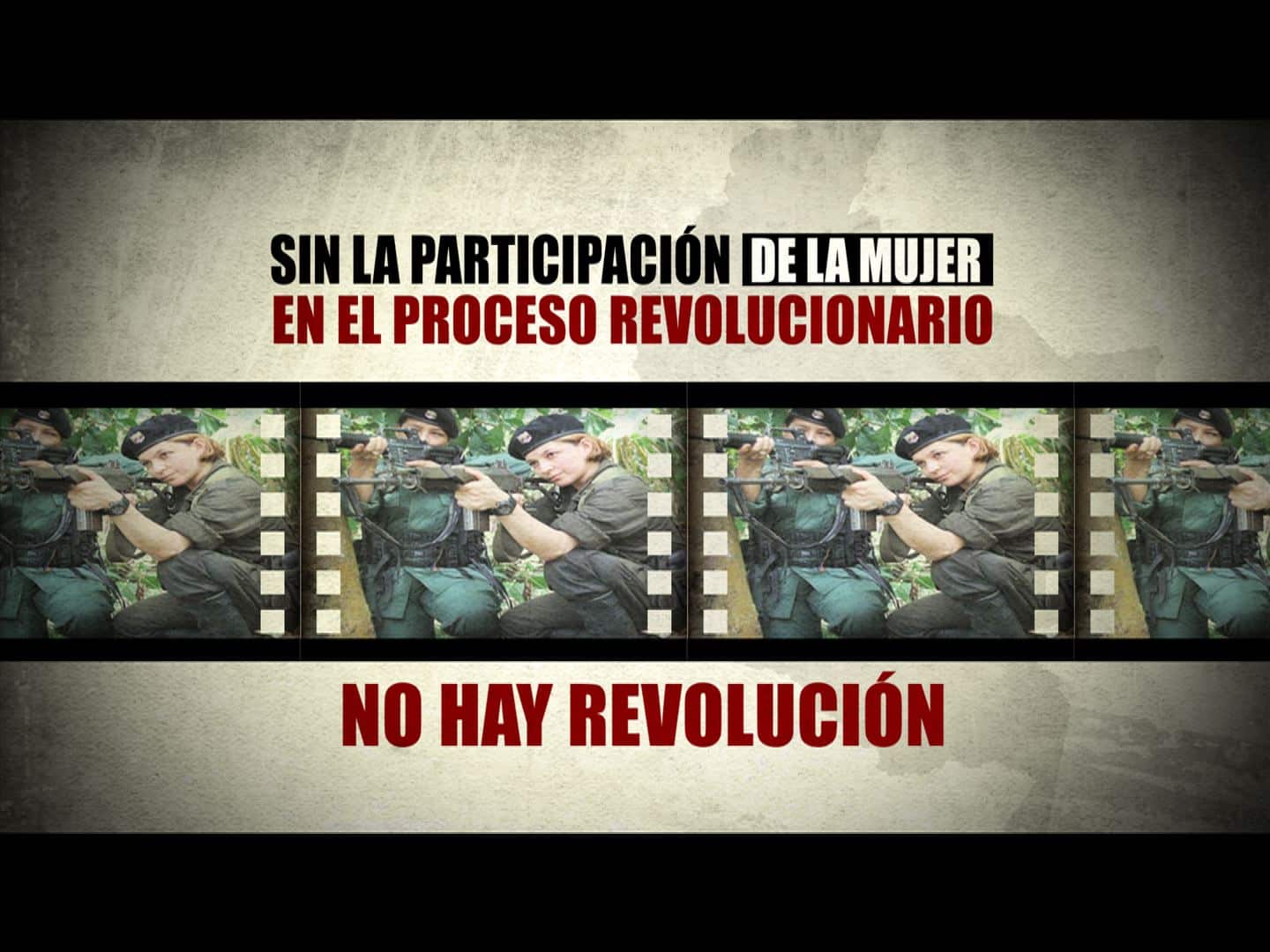

Still from Rosas y Fusiles |

How, then, to understand the importance of women in the struggle of the FARC-EP? Why is it that, as Victoria Sandino says, “a revolution without the participation of women is impossible”? Perhaps the key lies in the old idea that says those groups, the ones that a society’s structure places between a rock and a hard place, are the very ones called upon by history to change the society. This is what is called a historical mission. Nothing could better describe the position of Colombian women, whose situation cannot be improved without fundamental changes in the whole society. For this reason, the most conscious sector of Colombian women has often taken up arms to change their country’s oppressive conditions.

Today that same mission may call for new tactics. With profound changes occurring in many Latin American countries and the resurgence of Colombia’s popular movement, insurgent men and women may find that they can now make peace to achieve the same goals once pursued with war. Whether that is possible or not depends on whether the Colombian state will change its tune and permit a democratic opposition. That is, whether it will be willing to allow the forces of change to become participants in normal, legal political activity. From this humble starting point — a “democratic window” paid for with the lives of many guerrilleras as well as guerrilleros — Colombia’s most committed and selfless political force could begin the process of dismantling the country’s structural injustices and thereby forging a lasting peace.

Chris Gilbert is professor of Political Science at the Universidad Bolivariana de Venezuela. Vilma Kahlo is a documentary filmmaker who is currently working on Rosas y Fusiles, a film about women in the FARC-EP. En Español: www.mujerfariana.co/index.php/nos-gusta/141-las-guerrilleras-de-las-farc-ep-parteras-de-la-historia.