Chinese President Xi Jinping: What Is His Background?

n 1980 Deng Xiaoping set 2020 as the completion date for his Reform and Opening program–a 40-year overhaul of China’s economy.

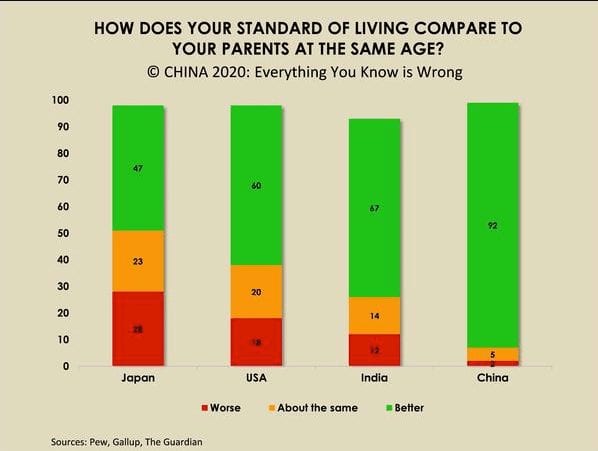

On June 1, 2021 President Xi will announce that all Deng’s goals have been reached and a basic xiaokang society established: no one is poor and everyone receives an education, has paid employment, more than enough food and clothing, access to medical services, old-age support, a home and a comfortable life–a claim no other country can make.

Lee Kwan Yew, Singapore’s Prime Minister for 30 years, said the primary responsibility of a government leader to “Paint his vision of the future to his people, translate that vision into policies which he must convince the people are worth supporting and, finally, galvanize them to help him implement them,”

A month after becoming President, in 2012, Xi painted his vision for Two Centennials: to fix inequality (‘socialist modernization’) by 2012 and to transform China into ‘a great modern socialist country, prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced, harmonious and beautiful’ by 2049. American Nobelist Robert Fogel agrees that China will be prosperous: its economy will be twice the size of Europe’s and America’s combined in 2049.

Because he must paint China’s new vision, colleagues granted Xi ‘core leader’ status in 2017 and amended the constitution in 2018 so he and PM can serve another term and make sure the new era gets off to a good start. Since he will be around until at least 2027, it may be a good idea to get to know him before our media intensify their attacks on him. Here’s a short bio.

People who have little experience with power–those who are far from it–tend to regard politics as mysterious and exciting. But I look past the superficialities, the power, the flowers, the glory, the applause. I see the detention houses, the fickleness of human relationships. I understand politics on a deeper level.–Xi Jinping, President of China.

Though wages had been doubling each decade for a generation, by 2009 local corruption was impacting faith in the national government and the Party needed a Confucian junzi–a combination of Bill Gates and Nelson Mandela–to retain its Heavenly Mandate. Ever-vigilant, the U.S. Embassy in Beijing was investigating a high born reformer who had triumphed over injustice yet remained compassionate, sincere, persistent and modest:

U.S. EMBASSY C O N F I D E N T I A L

SECTION 01 OF 06 BEIJING 003128

SIPDIS. 2009 November 16, 12:20 (Monday)

SUBJECT: PORTRAIT OF VICE PRESIDENT XI JINPING: ‘AMBITIOUS SURVIVOR’ OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION .Unlike those in the social circles the professor ran in, Xi Jinping could not talk about women and movies and did not drink or do drugs. Xi was considered of only average intelligence, the professor said, and not as smart as the professor’s peer group. Women thought Xi was ‘boring’.

The professor never felt completely relaxed around Xi, who seemed extremely ‘driven’. Nevertheless, despite Xi’s lack of popularity in the conventional sense and his ‘cold and calculating’ demeanor in those early years, the professor said, Xi was ‘not cold-hearted’. He was still considered a ‘good guy’ in other ways. Xi was outwardly friendly, ‘always knew the answers’ to questions, and would ‘always take care of you’. The professor surmised that Xi’s newfound popularity today, which the professor found surprising, must stem in part from Xi’s being ‘generous and loyal’.

Xi also does not care at all about money and is not corrupt, the professor stated. Xi can afford to be incorruptible, the professor wryly noted, given that he was born with a silver spoon in his mouth. In the professor’s view, Xi Jinping is supremely pragmatic, a realist, driven not by ideology but by a combination of ambition and ‘self-protection’.

Xi knows how very corrupt China is and is repulsed by the all-encompassing commercialization of Chinese society, with its attendant nouveau riche, official corruption, loss of values, dignity, and self-respect, and such ‘moral evils’ as drugs and prostitution, the professor stated. The professor speculated that if Xi were to become the Party General Secretary, he would likely aggressively attempt to address these evils, perhaps at the expense of the new moneyed class.

President Xi's father, Xi Zhongxun. A rare photo. Ironic that men who transformed humanity for the better through enormous personal effort are barely known and leave behind few traces, while criminals, false leaders, cretins and celebrities in the west have literally millions of pictures, and other objects of adoration to remember them by.

Xi inherited his silver spoon from a remarkable man. When the Japanese invasion interrupted his father’s schooling in 1933, Xi Zhongxun established a rebel area, commanded its army, expanded its territory, became a general at nineteen, provincial governor at twenty-two, the new Republic’s youngest Vice-Premier and one of the Revolution’s Eight Immortals. After escaping imprisonment by the Nationalists, Zhongxun was sentenced to death by fellow Communists for his outspokenly liberal views when Mao, emerging at the end of the Long March, reached his redoubt in Shaanxi Province in 1936 and pardoned him. Zhongxun spent the next twelve years alternating between governing and rescuing beleaguered armies. A superb negotiator–whose conversion of a rebel leader Mao compared to a famous conciliation in The Romance of the Three Kingdoms–he was widely loved and admired for his competence, outspokenness and honesty.

American journalist Sidney Rittenberg, a friend in the 1940s, recalled, “Xi Zhongxun took me with him a number of times traveling in the countryside among the villages and he knew whose baby was sick and whose grandpa had rheumatism and so forth, and he would go to these homes and talk to them and they loved him. He was always getting into trouble because of his plebeian style and democratic way of thinking. He was a very good man in my opinion, probably the most democratic-minded member of the old Party leadership. I just hope that a lot of this rubbed off on the son”.

Zhongxun’s non-ideological, pragmatic outspokenness got him jailed again, for seven years, during the Cultural Revolution. Rehabilitated, he was assigned to govern destitute Guangdong Province and Deng Xiaoping joked at his farewell, “The Government has no funds but we can give you favorable policies”. Finding Guangdong’s government blocking residents’ flight to neighboring Hong Kong–where wages were a hundred times higher–he risked re-imprisonment by proposing a special economic zone for private enterprise. After furious debate, Beijing approved his plan and he stabilized Guangdong, stopped the exodus, liberalized the economy and built China’s first free enterprise zone which, today, attracts Hong Kong graduates seeking better pay. His first son, Jinping, was born in Shaanxi Province in 1953 and grew up listening to his famous father’s stories, “He talked about how he’d joined the revolution and he’d say, ‘You’ll certainly make revolution someday’. He’d explain what revolution is. We heard so much of this our ears grew calluses”. In a Confucian land, Jinping’s high birth brought high expectations: “The primary duty of a son is to live an upright life and to spread the doctrines of humanity in order to win good reputation after death and thus reflect great honor upon his parents” The Book of Filial Duty.

Young Xi’s life in the public eye began inauspiciously. During the Cultural Revolution the twelve year old was paraded as an enemy of the people wearing a metal dunce cap and a placard around his neck before being sentenced to prison. But the juvenile detention center was full so he was sent to poverty-stricken Liangjiahe village as part of Mao’s “Up the Mountain and Down to the Countryside” campaign to educate privileged youth about rural life. When his tearful family farewelled him, “I told them if I didn’t go I wasn’t sure I’d survive”. His older sister stayed and, persecuted by radicals, committed suicide two years later.

He would spend seven years growing to manhood in Liangjiahe, sleeping on brick beds in flea-infested cave homes, enduring the peasants’ life of hunger and cold, ploughing, pulling grain carts and collecting manure. “Just after I arrived in the village beggars started appearing and, as soon as they turned up, the dogs would be set on them. Back then we students, sent down from the cities, believed beggars were bad elements and tramps. We didn’t know the saying, ‘in January there is still enough food, in February you will starve, and March and April you are half alive, half dead’. For six months every family lived only on bark and herbs. Women and children were sent out to beg so that the food could go to those who were doing the spring ploughing. You had to live in a village to understand it. When you think of the difference between what the central government in Beijing knew and what was actually happening in the countryside, you have to shake your head”.

Liangjiahe’s farmers rated the city boy six on a ten-point scale, “Not even as high as the women,” he said. “I was very young when I was sent to the countryside, it was something I was forced to do. At the time I didn’t think far ahead and gave no thought to the importance of cooperation. While the villagers went up the slopes and worked every day, I did as I chose and people got a poor impression of me so, after a few months, they sent me back to Beijing and I was placed in a study group. When I was released six months later I thought hard about returning to the village and talked to my uncle who had been active in revolutionary work in the 1940s. My uncle told me about his work back then and about how important it is to cooperate with the people you live with and that settled it. I went back to the village, got down to work and learned to cooperate. Within a year I was doing the same work as people in the village, living as they lived and working hard. The hardship of working shocked me, though eventually I could carry a shoulder pole weighing more than a hundred pounds up a mountain road. People saw that I had changed”. The only reliable light was provided by old kerosene lamps and the village had neither running water nor electricity. There was no school but he was ‘always reading books as thick as bricks,’ villagers recall. He began to lead small projects like reinforcing riverbanks and organizing a blacksmiths’ cooperative and constructed the first sewage system in the county, “The pipe from the pond was blocked and I unblocked it. Excrement and urine flew all over my face”. From plans sent by his mother he built a methane digester that gave Liangjiahe reliable light at night and eventually the county named him ‘a model educated youth’–a prerequisite for admission to university during the Cultural Revolution–and awarded him a motorcycle which he exchanged for a two-wheeled tractor, a rice mill and a submersible pump.

After repeated rejections because of his father’s imprisonment he was admitted to the Communist Party in 1974, the village elected him Village Party Secretary and, at twenty-two, his political career was launched. The following year he was accepted by Tsinghua University and a dozen villagers walked the twenty miles with him to the railhead, “It was the second time I cried there. The first time was when I got the letter saying that my big sister had died”. “Experiencing such an abrupt change from Beijing to a place so destitute affected me profoundly,” he later recalled.

He returned to Beijing to greet a father who, released after seven years in solitary confinement, was unable to recognize his grown sons and recited a familiar Tang poem: Returning to my home village after years of absence, My brows have grayed though my accent is unchanged. Children who meet me don’t recognize me. Laughing, they ask, what village do you come from? After graduation from Tsinghua his father’s old comrade-in-arms, Geng Biao, made him Personal Secretary to the Minister of National Defense and the twenty-four-year-old spent three years in uniform, studying the vast military he was destined to command.

His father urged him to enter government while friends and classmates were going into business or studying abroad so he left Beijing to begin a twenty-five year apprenticeship administering villages, townships, cities, counties and provinces across the country. Along the way, he picked up a PhD for a dissertation on rural marketization. Like his father, he was effective, diligent and versatile and left a trail of prosperity behind him as he rose through the ranks. Posted to backward Zhengding County, Hebei Province in 1982, he demonstrated the paternal flair for economic development: learning that a TV production of The Dream of Red Mansions was scouting locations, he persuaded the county to employ local craftsmen to build real mansions instead of temporary sets. Fees from the production company paid most of the construction cost and, as soon as shooting ended, he turned the set into a tourist attraction that still hosts a million paying visitors each year and has been the backdrop of hundreds of productions.

Promoted to the governorship of Fujian Province, he upgraded its Internet, networked the provincial hospitals’ medical records and made government transactions accessible on line. He sent officials to work in villages throughout the province and set up citizens’ committees of to supervise village Party Committees–an innovation Beijing legislated nationally as The Organic Law of Villagers’ Committees. He was the first governor to crack down on food contamination and created the first provincial environmental monitoring system. Today, Fujian’s pristine environment attracts high tech startups. Appointed Zhejiang Provincial Party Secretary in 2002, he fundraised fifty percent of the five hundred million dollar cost of the twenty-two mile Hangzhou Bay Bridge, the world’s longest, from local businesses. “Private funds have infiltrated all walks of life here,” he told a visitor, echoing his father.

Earnest, blunt to the point of rudeness and a workaholic, his track record ranked high in Beijing’s annual surveys. He was, in the words of U.S. Treasury Secretary Hank Paulsen, “The kind of guy who knows how to get things over the goal line”. Like his father, he possessed immense energy for work, as Taiwanese businessman Li Shih-Wei, who saw him regularly, told The Washington Post, “When we discussed my problems he would listen closely, track the issue and try to find solutions. His working efficiency was pretty high–quite rare among the officials we encountered there. Meetings were usually in the government cafeteria, not the fancy restaurants most officials chose. His lifestyle wasn’t luxurious”. Xi encouraged initiative with policies like ‘special procedures for special cases’, and ‘do things now,’ urged officials to meet people face to face and set an example by meeting seven hundred petitioners in forty-eight hours.

A regular at farmers’ markets, on fishing boats and down coal mines, he became a local celebrity for being the first local Party Secretary to visit all the villages in Zhengding County, a performance he repeated everywhere he governed and, after becoming President, visited all of China’s 33 provinces, regions and municipalities. His only recorded outbursts were over corruption. According to one Zhejiang official, Xi ‘kept his reputation wholesome and untainted by allegations of corruption’ and, under a pen name, contributed hundreds of earnest opinion pieces to local dailies: “If we remain aloof from ordinary people we will be like a tree cut off from its roots. Officials at all levels must change their style, get close to ordinary people, try their best to do good things for them, put aside the haughty manner of feudalism and set a good example”. In an essay on graft he said, “Transparency is the best anti-corrosive and as long as we embrace democracy, go through a proper procedures and avoid ‘black’ case work, fighting corruption won’t be just empty words”. “How important the people are in the minds of an official will determine how important officials are in the minds of the people. Officials should love the people in the way they love their parents, work for their benefit and lead them to prosperity”.

He waited twenty years to give his first public interview, and his advice was prosaic, “Politics is risky. Lots of people who’ve experienced failures reproach themselves: ‘I’ve helped so many people, I’ve done so much and all I get is ingratitude. People don’t understand me. Why must it be this way?’ Some colleagues who started when I did gave up their jobs for such reasons. But if you have a position somewhere, if you stick to it and continue your work then, in the end, it will produce results. The essence of success is to fasten onto your assignment and continue working. I’ve come across many difficulties and obstacles. That’s inevitable. Going into politics is like crossing a river. No matter how many obstacles you meet there is only one direction, and that’s forward”.

In 2007, after Shanghai officials looted its pension fund, he was assigned to clean up the giant city, a sinkhole of iniquity for centuries. He turned the governor’s mansion into a veterans’ home, promoted green, sustainable development and pushed Shanghai to become a leading financial center–drawing a relieved headline4 in the People’s Daily: ‘Glad to Hear Some Good News from Shanghai at Last’. Today, Shanghai’s pension fund is in surplus, its police are noted for their honesty, its courts a preferred international forum and its education system the best in the world. In 2008 Xi produced a flawless Beijing Olympic Games, on time, on budget and without a hint of corruption–while coordinating the military, police, bureaucracy, localities, diplomacy, security, logistics, media and the environment–a feat that made him a leading contender for the presidency.

In a patriarchal society, fond memories of his father could only help.

Though our media refer to Xi as ‘President’ (President Trump called him ‘the King of China’), China has no such office and no Chinese official resembles an American President, about whom Lincoln’s Secretary of State, William Henry Seward, observed, “We elect a king for four years and give him absolute power within certain limits which, after all, he can interpret for himself”. While American Presidents hire and fire their administrative teams, make war, pardon, imprison or assassinate enemies Chinese leaders, even Mao, are board chairmen only. They can set agenda and direct discussion but, ultimately, must follow to the votes of the seven-man Steering Committee, none of whom they chose or can dismiss–and virtually all Steering Committee decisions are unanimous.

Xi’s primary leadership responsibilities were spelled out in the Twelfth Five Year Plan which, as a member of the Politburo Standing Committee for the previous five years, he helped draft: double national wages and pensions during his tenure, clean up corruption, reform the military, pass a stalled Social Security bill and, by December, 2020, deliver the Party’s xiaokang promise: ‘a society in which no one is poor and everyone receives an education, has paid employment, more than enough food and clothing, access to medical services, old-age support, a home and a comfortable life’.

Xi’s style fits the Chinese mold: his speeches are businesslike, soft-spoken, non-confrontational and his first presidential address was retail politics, “People expect better wages, higher quality medical care, more comfortable homes and a more beautiful environment”. He invited the Carter Center to help expand democratic participation in policy-making, called for a greater role for the constitution in state affairs, strengthened Congressional participation in interpreting the constitution and generating citizens’ involvement in the legislative process. Promising to tackle corruption, he quoted Confucius, “He who rules by virtue is like the North Star, which maintains its place and the multitude of stars pay homage,” and placed responsibility for integrity squarely on official shoulders. His most sensational political gesture was lunching at the communal table in a Beijing dumpling restaurant and chatting with customers for twenty minutes without security.

Though not as precocious as his father, he proved comparably effective. The piecemeal, outdated, inconsistent legal code and judicial unpredictability he inherited had undermined people’s faith in the legal system. He reformed the legal system, abolished laogai re-education through labour, eliminated local government interference in the courts, called for transparency in legal proceedings and professionalization of the legal workforce and the Supreme People’s Court agreed to broadcast its proceedings live. He formed cross-jurisdictional squads of officials to coordinate corruption investigations, gave them independence, filed a million disciplinary cases and prosecuted a hundred ministers, generals, senior executives, university chancellors and private CEOs.

Abroad, he turned the Shanghai Cooperative Organization, SCO, into the largest political confederation on earth, uniting half the world’s people and four nuclear powers–Russia, China, India and Pakistan–in a single security zone. In 2013 he offered to finance the Belt and Road Initiative, BRI, a ten trillion dollar program of roads, railways, telecommunications, energy pipelines and ports integrating the Eurasian continent from Barcelona to Beijing into a seamless, secure, integrated market.

In 2017 he broke ground on Jing-Jin-Ji, an 82,000 square mile green megacity with the population of Japan. It will integrate Beijing’s financial, regulatory and research strengths with Tianjin’s port and Hebei’s technology using seven hundred miles of new rail lines, scheduled completion in 2020. In 2017 he initiated the transition to a dàtóng society by endorsing Social Credit, a transparent, publicly owned system ranking the creditworthiness of government departments and officials–from President down–businesses and citizens. More carrot than stick, it provides increasingly valuable benefits, from low-interest loans and no-deposit rentals to visa-free travel, with rising public reputation.

In 2018, the system blocked a developer’s attempt to fly first class to London and provided a tourist-class seat because he had persistently ignored court orders to pay his subcontractors.

The Future

[dropcap]B[/dropcap]ecause 2020 will mark the successful conclusion of Deng Xiaoping’s 1980 Reform and Opening program, it will be Xi’s responsibility to “Paint his vision of the future to his people, translate that vision into policies which he must convince the people are worth supporting and, finally, galvanize them to help him implement them,” which Lee Kwan Yew described as the primary responsibility of government leaders.

A month after becoming President, Xi described his Goals for Two Centennials: to spend 2020-2035 fixing inequality (‘socialist modernization’) and spend 2035-2049 transforming China into ‘a great modern socialist country, prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced, harmonious and beautiful’. According to American Nobelist Robert Fogel, China will certainly be prosperous: in 2049 its economy will be twice the size of Europe’s and America’s combined.

Because he must paint China’s new vision, colleagues granted Xi ‘core leader’ status in 2017 and amended the constitution in 2018 so he and Premier Li could serve more than two five-year terms, a move was greeted with some alarm. Li Datong, a prominent Party member and real estate developer, wrote, “I am a Chinese citizen, and a voter in Beijing. You are delegates chosen by us, and you represent us in political deliberations and in political action–and you represent us in exercising the right to vote. As I understand it, the stipulation in the 1982 Constitution that the national leaders of China may not serve for more than two terms in office was political reform measure taken by the Chinese Communist Party and the people of China after the immense suffering wrought by the Cultural Revolution. This was the highest and most effective legal restriction preventing personal dictatorship and personal domination of the Party and the government and a major point of progress in raising the level of political civilization in China in line with historical trends. It was also one of the most important political legacies of Deng Xiaoping. China can only move forward on this foundation, and there is emphatically no reason to move in the reverse direction. Removing term limitations on national leaders will subject us to the ridicule of the civilized nations of the world. It means moving backward into history, and planting the seed once again of chaos in China, causing untold damage”.

Wang Ying, a businesswoman and government reform advocate, called the proposal “An outright betrayal, against the tide of history. I know that you (the government) will dare to do anything and one ordinary person’s voice is certainly useless, but I am a Chinese citizen and don’t plan to leave. This is my motherland too!”

Chinese are always reluctant to judge current leaders; it takes decades, they say, to discover if their policies were beneficial, but what can we make of Xi at this stage? Lee Kwan Yew, who knew him personally, said, “I would put him in Nelson Mandela’s class of persons. Someone with enormous emotional stability who does not allow his personal misfortunes or sufferings to affect his judgment. In a word, he is impressive”.

Neither his character nor his track record has spared him the burdens of everyday government: in 2018, Xi was still trying to merge China’s provincial retirement funds into an American-style Social Security system–which he pointed to as a model–and making slow progress towards a national land tax. Politics is universal.

Sources

1 In a 2000 interview with the journalist Chen Peng. Chinese Times

2 The Book of Filial Duty.

4 How China’s Leaders Think: The Inside Story of China’s Past, Current and Future Leaders by Robert Lawrence Kuhn

From: China 2020: Everything You Know is Wrong forthcoming 2018, read a sample here.

SPECIAL EDITOR for Asian Affairs Godfree Roberts (Ed.D. Education & Geopolitics, University of Massachusetts, Amherst (1973)), currently resides in Chiang Mai, Thailand. His expertise covers many areas, from history, politics and economics of Asian countries, chiefly China, to questions relating to technology and even retirement in Thailand, a topic of special interests for many would-be Western expats interested in relocating to places where a modest income can still assure a decent standard of living and medical care.

SPECIAL EDITOR for Asian Affairs Godfree Roberts (Ed.D. Education & Geopolitics, University of Massachusetts, Amherst (1973)), currently resides in Chiang Mai, Thailand. His expertise covers many areas, from history, politics and economics of Asian countries, chiefly China, to questions relating to technology and even retirement in Thailand, a topic of special interests for many would-be Western expats interested in relocating to places where a modest income can still assure a decent standard of living and medical care.

[premium_newsticker id=”154171″]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

In his zeal to prove to his antagonists in the War Party that he is as bloodthirsty as their champion, Hillary Clinton, and more manly than Barack Obama, Trump seems to have gone “play-crazy” -- acting like an unpredictable maniac in order to terrorize the Russians into forcing some kind of dramatic concessions from their Syrian allies, or risk Armageddon.However, the “play-crazy” gambit can only work when the leader is, in real life, a disciplined and intelligent actor, who knows precisely what actual boundaries must not be crossed. That ain’t Donald Trump -- a pitifully shallow and ill-disciplined man, emotionally handicapped by obscene privilege and cognitively crippled by white American chauvinism. By pushing Trump into a corner and demanding that he display his most bellicose self, or be ceaselessly mocked as a “puppet” and minion of Russia, a lesser power, the War Party and its media and clandestine services have created a perfect storm of mayhem that may consume us all.— Glen Ford, Editor in Chief, Black Agenda Report

In his zeal to prove to his antagonists in the War Party that he is as bloodthirsty as their champion, Hillary Clinton, and more manly than Barack Obama, Trump seems to have gone “play-crazy” -- acting like an unpredictable maniac in order to terrorize the Russians into forcing some kind of dramatic concessions from their Syrian allies, or risk Armageddon.However, the “play-crazy” gambit can only work when the leader is, in real life, a disciplined and intelligent actor, who knows precisely what actual boundaries must not be crossed. That ain’t Donald Trump -- a pitifully shallow and ill-disciplined man, emotionally handicapped by obscene privilege and cognitively crippled by white American chauvinism. By pushing Trump into a corner and demanding that he display his most bellicose self, or be ceaselessly mocked as a “puppet” and minion of Russia, a lesser power, the War Party and its media and clandestine services have created a perfect storm of mayhem that may consume us all.— Glen Ford, Editor in Chief, Black Agenda Report

window.newShareCountsAuto="smart";