The Biggest Threat to the 99% Isn’t the 1%, It’s the 0.1%

Unpack the numbers on the highest earners in the US, and there’s a stark division between the well-off and the dangerously affluent 0.1%, such as Dimon.

“We are the 99 percent” is a great slogan, but is it distracting our attention from a sinister reality? There’s strong evidence that it’s not the 1 percent you should worry about — it’s the 0.1 percent. That decimal point makes a big difference.

Over the last decade, a gigantic share of America’s income and wealth gains has flowed to this group, the wealthiest one out of 1,000 households. These are the wildly exotic and rapidly growing plants in our economic hothouse. Their habits and approaches to life are far divorced from the rest of us, and if we let them, they will soon cut off all our air and light.

The 99 percent would do well to find common ground with the bulk of the 1 percent if we can, because we are going to need each other to tackle this mounting threat from above.

To make it into the 1 percent, you need to have, according to some estimates, at least about $350,000 a year in income, or around $8 million accumulated in wealth. At the lower end of the 1 percent spectrum, the “lower-uppers,” as they have been called, you’ll find people like successful doctors, accountants, engineers, lawyers, vice-presidents of companies, and well-paid media figures.

Plenty of these affluent people have enjoyed blessings from Lady Luck, but a lot of them work hard at their jobs and want to contribute to their communities in positive ways. In times past, these kinds of citizens served on the boards of museums and cultural institutions and were active and prominent figures in their towns and cities. But now they are getting shoved aside unceremoniously by the vastly richer Wall Street financiers and Silicon Valley tycoons above them.

Those at the lower end of the 1 percent have very nice houses and take exotic vacations, but they aren’t zipping to and fro in personal helicopters or cruising the high seas in megayachts. In exorbitantly expensive places like New York City and San Francisco, the lower-uppers may not even feel particularly rich. Most of them aren’t really growing their share of wealth and plenty are worried about tumbling down the economic ladder. They have reason to worry.

Some lower-uppers are beginning to realize that their natural allies are not those above them on the economic ladder. They are getting the sense that the 0.1 percent is its own hyper-elite club, and lower-uppers are not invited to the party. The 0.1 percent has pulled away because at the tippy top, income has grown much faster than it has for the rest of the affluent. Unlike the lower-uppers, the super-rich folks are armed with every tax dodge in the universe: they aren’t expected to pay nearly their share to Uncle Sam. Their income comes largely from capital gains, which are taxed at a far lower rate than income earned from working. (You wonder who passed that convenient piece of legislation, uh?—Eds.) As their money piles up higher and higher, their conspicuous consumption knows no bounds — they are building palatial homes and massive art collections and even gold-plated bunkers to protect themselves in case of an uprising. Many don’t really ever put down roots in communities; they roam from New York to London to Dubai to the Cayman Islands, following the favorability of weather and tax codes.

All told, the 0.1 percent now owns about as much wealth as the bottom 90 percent of America combined. And that’s just the official numbers. Plenty of their wealth is parked overseas and in places where it’s hard to get an accurate count of what they’ve accumulated. To get into the club, which comprises around 115,000 households, you need to start with a nest egg of $20 million — and that’s at the very bottom of the super-rich group. George W. Bush just barely makes the cut. He’s very rich, but not among the highest fliers in today’s second Gilded Age.

As you move on up the 0.1 percent ladder, you get folks like Steve Cohen, the hedge fund billionaire who bought a 14-foot shark in formaldehyde for his office, as if to signal his shady business practices (his previous firm, SAC Capital, was shut down by the feds for insider trading). Cohen doesn’t have just one mansion, he has lots of them. His $23 million principal home is in Greenwich, Connecticut, featuring an indoor basketball court, a glass-enclosed pool, a 6,700-square-foot ice skating rink with a Zamboni machine that smoothes the ice, a golf course and a private art museum. He also has five other homes just in the New York area alone.

People like Cohen are a big part of the undue concentration of wealth at the expense of workers and communities — they create little of value for society and siphon off funds for our schools and infrastructure with tax loopholes allowed by bought politicians, like the notorious “carried interest” loophole. You also get bankers CEOs like Jamie Dimon of JPMorgan Chase and corporate chieftains paid stratospheric salaries even while driving their companies into the ground, like erstwhile GOP presidential hopeful Carly Fiorina, formerly of Hewlett Packard.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]t used to be that simply being a billionaire would get you into the Forbes 400 list — that was true up until 2006. No more. Our current herd of fatcats has blown past their Gilded Age counterparts to seize an even more gigantic share of the economic pie. According to the magazine, in 2014 you had to have $1.55 billion in the bank vault to make the list. That was $250 million more than in 2013. By 2015, you had to have even more: Carol Jenkins Barnett, whose wealth derives from Publix supermarkets, was too poor to make Forbes with her paltry $1.69 billion.

The hurdle continues to rise rapidly. By 2015, the wealthiest 20 people owned more wealth than half the American population. This group is where you’ll find Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook and Larry Page of Google, as well as the most successful financiers, like Warren Buffett and George Soros. But the ranks of the very top are no longer filled mainly by entrepreneurs or even financiers who are self-made. Increasingly, they are populated by people who, thanks to several decades of regressive tax policy, have inherited their wealth; names like Walton and Koch have become common at the apex of wealth. This is the new hereditary aristocracy of means and power.

Figuring out exactly how the very richest spend politically is hard, but it’s obvious that big contributions from the 0.1 percent are sharply rising in importance. It used to be that these gazillionaires would make their donations and then simply pick up the phone and tell Congress what they wanted done — as Jamie Dimon did when he and other bankers wanted a key part of Dodd-Frank to be rolled back in 2014. They tend to get what they want (Dimon did), and above all, what they want is not to pay taxes or have their activities regulated. That’s why you will continue to hear politicians insist that the paltry amount you can expect in Social Security is too much and that “we can’t afford” to send kids to college without plunging them into debt peonage.

Inequality of income and wealth has fed back into the political process in dramatic fashion this political season. Tycoons like Donald Trump are abandoning their behind-the-scenes positions and stepping right onto the political stage. We may be entering a new phase of American politics where the 0.1 percent more regularly takes on the mantle of public servant to run the show directly, highlighting the brokenness of our system of democratic representation. Bernie Sanders, who has made political revolution focused on wresting control from billionaires as a central theme, is clearly focused on the power of the 0.1 percent. The revolution he calls for will not likely happen unless the 99 percent and the lower-uppers can appreciate their common ground and common threat.

Mike N., a North Carolina physician and entrepreneur, is a member of the 1 percent, but not in the 0.1 percent stratosphere. “Growing inequality is bad for everyone,” he wrote to me. “I do not believe that is sustainable.” He identifies with people who have a tough time making ends meet because he did this for most of his life before his career took off. He is concerned with serving the community through charitable work and political engagement, and he believes that “all should have the opportunity for things like education and healthcare.” Mike N. is the kind of person the 99 percent can work with.

Unless we act boldly — together — to reduce private concentrations of wealth, inequality will continue to grow and that 0.1 percent will continue to explode because the returns on their wealth exceed increases in salaries and income, as Thomas Piketty noted in his book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century. They can get wealthier and wealthier just by sitting there doing absolutely nothing. In fact, it would be better if they did just sit there and do nothing, because when they do something, it is often reckless speculation that destabilizes the economy. By seriously taxing our wealthiest households, we could raise significant revenues and invest these funds to expand wealth-building opportunities across the economy.

Until we are able to offer a challenge to the 0.1 percent, we will continue to see democracy undermined, social cohesion blown apart, economies destabilized, social mobility stalled, and many other important aspects of our personal and public lives degraded, including our health. We need the lower-uppers to construct a social and political movement big enough and powerful enough to do it.

Lynn Stuart Parramore is an AlterNet contributing editor.

Note to Commenters

Due to severe hacking attacks in the recent past that brought our site down for up to 11 days with considerable loss of circulation, we exercise extreme caution in the comments we publish, as the comment box has been one of the main arteries to inject malicious code. Because of that comments may not appear immediately, but rest assured that if you are a legitimate commenter your opinion will be published within 24 hours. If your comment fails to appear, and you wish to reach us directly, send us a mail at: editor@greanvillepost.com

We apologize for this inconvenience.

=SUBSCRIBE TODAY! NOTHING TO LOSE, EVERYTHING TO GAIN.=

free • safe • invaluable

[email-subscribers namefield=”YES” desc=”” group=”Public”]

Nauseated by the

vile corporate media?

Had enough of their lies, escapism,

omissions and relentless manipulation?

Send a donation to

The Greanville Post–or

But be sure to support YOUR media.

If you don’t, who will?

Venezuela’s Opposition: Attacking Its Own People

//

=By= Eric Draitser

Images from top to bottom, left to right: Opposition march in Caracas on 12 February 2014, Peaceful march in Maracaibo, Protests at Altamira Square, “Camp Freedom” outside of the UN headquarters in Caracas, March in Caracas following the arrest of Leopoldo Lopez. Zfigueroa

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he corporate media would have you believe that Venezuela is a dictatorship on the verge of political and economic collapse; a country where human rights crusaders and anti-government, democracy-seeking activists are routinely rounded up and thrown in jail. Indeed, the picture from both private media in Venezuela, as well as the mainstream press in the U.S., is one of a corrupt and tyrannical government desperately trying to maintain its grip on power while the opposition seeks much-needed reforms. In fact, the opposite is true.

The sad reality of Venezuela is that it is the Bolivarian Revolution that is being undermined, targeted, and destabilized. It is the Socialist Party, its leftist supporters (and critics), Chavista activists and journalists, and assorted forces on the Left that are being victimized by an opposition whose singular goal is power. This opposition, now in the majority in the National Assembly, uses the sacrosanct terminology of “freedom,” “democracy,” and “human rights” to conceal the inescapable fact that it has committed, and continues to commit, grave crimes against the people of Venezuela in the service of its iniquitous agenda, shaped and guided, as always, by its patrons in the United States.

This so-called opposition – little more than the political manifestation of the former ruling elites of Venezuela – wants nothing less than the total reversal of the gains of the Bolivarian Revolution, the end of Chavismo, and the return of Venezuela to its former status as oil colony and wholly owned subsidiary of the United States. And how are these repugnant goals being achieved? Economic destabilization, street violence and politically motivated assassinations, and psychological warfare are just some of the potent weapons being employed.

Making the Economy Scream

In what is perhaps the most infamous example of U.S. imperialism in Latin America in the last half century, the Nixon administration, led by Henry Kissinger, orchestrated the 1973 overthrow of Salvador Allende, the Socialist president of Chile. In declassified CIA documents, it has been revealed that President Nixon famously ordered U.S. intelligence to “make (Chile’s) economy scream,” a reference to the need to undermine and destabilize the Chilean economy using both U.S. financial weapons, and a powerful business elite inside Chile, in order to pave the way for either the collapse of the government or a coup d’etat. Sadly, U.S. efforts proved successful, leading to a brutal dictatorship that lasted nearly two decades.

The same effort is currently underway in Venezuela, where the economic difficulties the country is facing can be directly attributed to the insidious efforts of Venezuela’s right-wing opposition, and its backers in the United States. While corporate media reports over the last two years have shown viscerally shocking images of empty store shelves, blaming supply problems on the incompetence and corruption of the Maduro government, none of the stories bother to examine the question of why supplies have dwindled in the way they have.

There is analysis pointing to corruption, an important problem to be tackled, to be sure, as well as lack of access to capital, and myriad other issues. But never does one find the real crux of the problem being discussed: supply and distribution remains in the hands of the right-wing elites whose interests are served by making life unbearable for the masses of poor and working people.

As renowned economist and former Venezuelan ambassador to the United Nations, Julio Escalona explained in Caracas on the eve of the December 2015 elections which ushered the right-wing back into the National Assembly: “The majority of Venezuela’s imports and distribution networks are in the hands of the elite … Many of the goods needed for Venezuelan consumption are diverted to Brazil and Colombia. We are experiencing manufactured scarcity, a crisis deliberately induced as a means of destabilization against the government … This is psychological war waged against the people of Venezuela in an attempt to intimidate them into abandoning the government and the socialist project entirely.”

The significance of this point cannot be overstated, as the lack of basic necessities, coupled with daily obstacles such as long lines at supermarkets, is enough to bring hardened Chavista activists, let alone ordinary Venezuelans, to question or even abandon the political project. And that is precisely the goal – make the economy scream, so the Chavistas will shut their mouths.

Of course, there’s little doubt that the scarcity of goods is largely manufactured for political ends. One need only look at the conspicuous reappearance of goods in the immediate aftermath of the right-wing Unity Roundtable victory in the December 2015 elections to see how connected the supply problems are with political agendas. Additionally, massive hoarding of basic consumer goods in warehouses owned by prominent Venezuelan business interests sheds added light on the lengths to which the right-wing opposition and elites will go to make their own country’s economy scream.

And then there’s the economic elephant in the room: oil. According to OPEC figures, oil revenue accounts for roughly 95 percent of Venezuela’s export earnings, with the energy sector comprising roughly a quarter of the gross domestic product. In eighteen months, from April 2014 to January 2016, the price per barrel of crude oil has dropped from US$108 to under US$30, a drop of nearly 75 percent. This price collapse has devastated Venezuela’s economy as oil revenue is needed to provide everything from basic services to the continuation of the public housing mission. And while President Maduro has refused to implement austerity, the drop has undeniably impacted the overall economy.

But is this price collapse merely the product of “simple economics” as the New York Times recently wrote? Or is it yet another orchestrated assault on oil-producing nations targeted by the U.S.? Russian President Vladimir Putin certainly implied that in late 2014 as the oil plunge took shape. Putin stated, “There’s lots of talk about what’s causing (the lowering of the oil price). Could it be the agreement between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia to punish Iran and affect the economies of Russia and Venezuela? It could.” Indeed, the collapse of oil couldn’t have come at a more opportune time for the U.S. globally, or for the U.S. proxy opposition inside Venezuela, as the effects of the plunge had obvious and immediate political ramifications.

One should also include hyper-speculation against Venezuela’s currency on the list of economic weapons being employed. Everything from the removal of currency and commodities out of the country, to the fostering and promotion of black market currency exchanges, has driven inflation through the roof in the country. While economic policy and mismanagement indeed play a role in this, it is equally true that the bolivar is yet another victim of the economic war.

It would be very difficult for any country to manage to ride out the confluence of negative economic developments and domestic economic subversion that Venezuela has had to endure. But coupled with a campaign of political violence and psychological war, the destabilization has taken on new dimensions.

In the U.S., and throughout North America and Europe, when one hears of violence in Venezuela, it is almost always either in the context of street violence or alleged “brutal crackdowns” on political protesters. However, the real political violence is carried out by the right-wing opposition, its paramilitary allies, and their backers in the U.S.

Violence sends a very clear message throughout Venezuelan society: do not stand up for your rights, do not try to defend the Revolution.

Perhaps no targeted killing has had a greater impact on the country and the Revolution than the 2014 assassination of Robert Serra, a young, up-and-coming legislator from the PSUV who was murdered by individuals connected to former Colombian President and self-declared enemy of the Bolivarian Revolution, Alvaro Uribe. Serra was seen by many as the future of the PSUV and of the Chavista movement in the country. His murder was interpreted by millions as a direct assault on the Revolution and the future of the country.

Just this year, Venezuela has seen a number of other assassinations carried out by the same networks backed by the right wing and their international allies. The well-respected journalist and prominent Chavista Ricardo Duran was murdered outside his home in Caracas. Likewise, Fritz St. Louis, International Coordinator of the United Socialist Haitian Movement and Secretary General of the Haitian Cultural House Bolivariana de Venezuela, was assassinated. Recently, Venezuela also saw opposition “activists” in the western city of San Cristobal brutally run down two police officers after the “protesters” hijacked a bus.

Sadly, there are many more killings that could be listed here. Such political violence is yet another indication of the “dirty war” – to borrow a term all too familiar in Latin America – being waged against the Bolivarian Revolution and Venezuela’s government.

This sort of violence sends a very clear message throughout Venezuelan society: do not stand up for your rights, do not try to defend the Revolution.

And that message is continually hammered home by a right-wing media that is, in effect, the propaganda arm of the right-wing opposition and the United States. As author and investigative journalist Eva Golinger revealed in 2007, the U.S. funded a program to provide financial support to Venezuelan journalists hostile to Chavez and the Bolivarian Revolution. This was a concerted effort aimed at influencing public opinion through the right-wing media, shaping the views of Venezuelans against their government. And that propaganda assault continues to this day, utilizing every possible means of disinformation and misinformation to turn the people of Venezuela against the Bolivarian Revolution, and against the socialist project.

The opposition and its U.S. patrons ceaselessly trumpet democracy and human rights, while having no regard for either in Venezuela. From quite literally taking food from the mouths of Venezuelans, to wantonly killing Chavistas and citizens alike, the opposition has proven itself to be not just reactionary and anti-democratic, but brazenly criminal.

In these times of political and economic turmoil in the Bolivarian Republic, one must recall just what exactly the so-called “opposition” is. And one must equally consider what sort of country Venezuela will become were they to be given even the slightest bit more power.

Eric Draitser is the founder of Stop Imperialism and is a freelance journalist.

Source: TeleSur

Note to Commenters

Due to severe hacking attacks in the recent past that brought our site down for up to 11 days with considerable loss of circulation, we exercise extreme caution in the comments we publish, as the comment box has been one of the main arteries to inject malicious code. Because of that comments may not appear immediately, but rest assured that if you are a legitimate commenter your opinion will be published within 24 hours. If your comment fails to appear, and you wish to reach us directly, send us a mail at: editor@greanvillepost.com

We apologize for this inconvenience.

Nauseated by the

Nauseated by the

vile corporate media?

Had enough of their lies, escapism,

omissions and relentless manipulation?

Send a donation to

The Greanville Post–or

But be sure to support YOUR media.

If you don’t, who will?

Watch Out for Judicial Coup in Brazil

//

=By= Alfredo Saad-Filho

President Dilma. Rede Brasil Atual. (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The judicial coup against President Dilma Rousseff is the culmination of the deepest political crisis in Brazil for 50 years.

[dropcap]E[/dropcap]very so often, the bourgeois political system runs into crisis. The machinery of the state jams; the veils of consent are torn asunder and the tools of power appear disturbingly naked. Brazil is living through one of those moments: it is dreamland for social scientists — a nightmare for everyone else.

Dilma Rousseff was elected President in 2010, with a 56-44 percent majority against the right-wing neoliberal PSDB (Brazilian Social Democratic Party) opposition candidate. She was reelected four years later with a diminished yet convincing majority of 52-48 percent — a margin of 3.5 million votes.

Dilma’s second victory sparked a heated panic among the neoliberal and US-aligned opposition. The fourth consecutive election of a President affiliated to the center-left PT (Workers’ Party) was bad news for the opposition, because it suggested that PT founder Luís Inácio Lula da Silva could return in 2018. Lula had been President between 2003 and 2010, and when he left office his approval ratings hit 90 percent, making him the most popular leader in Brazil’s history. This likely sequence suggested that the opposition could be out of federal office for a generation. The opposition immediately rejected the outcome of the vote. No credible complaints could be made, but no matter; it was resolved that Dilma Rousseff would be overthrown by any means necessary. To understand what happened next, we must return to 2011.

Dilma inherited from Lula a booming economy. Alongside China and other middle-income countries, Brazil bounced back vigorously after the global crisis. GDP expanded by 7.5 percent in 2010, the fastest rate in decades, and Lula’s hybrid neoliberal-neodevelopmental economic policies seemed to have hit the perfect balance: sufficiently orthodox to enjoy the confidence of large sections of the internal bourgeoisie, and heterodox enough to deliver the greatest redistribution of income and privilege in Brazil’s recorded history, thereby securing the support of the formal and informal working class. For example, the minimum wage rose by 70 percent and 21 million (mostly low-paid) jobs were created in the 2000s. Social provision increased significantly, including the world-famous Bolsa Família conditional cash transfer program, and the government supported a dramatic expansion of higher education, including quotas for blacks and state school pupils. For the first time, the poor could access education as well as income and bank loans. They proceeded to study, earn, and borrow, and to occupy spaces previously monopolized by the upper middle class: airports, shopping malls, banks, private health facilities, and roads, which were clogged up by cheap cars purchased in 72 easy payments. The government coalition enjoyed a comfortable majority in a highly fragmented Congress, and Lula’s legendary political skills managed to keep most of the political elite on his side.

Then everything started to go wrong. Dilma Rousseff was chosen by Lula as his successor. She was a steady pair of hands and a competent manager and enforcer. She was also the most left-wing President of Brazil since João Goulart, who was overthrown by a military coup in 1964. However, she had no political track record and, it would later become evident, lacked essential qualities for the job.

Once elected, Dilma shifted economic policies further away from neoliberalism. The government intervened in several sectors seeking to promote investment and output, and put intense pressure on the financial system to reduce interest rates, which lowered credit costs and the government’s debt service, releasing funds for consumption and investment. A virtuous circle of growth and distribution seemed possible. Unfortunately, the government miscalculated the lasting impact of the global crisis. The US and European economies stagnated, China’s growth faltered, and the so-called commodity supercycle vanished. Brazil’s current account was ruined. Even worse, the US, UK, Japan, and the Eurozone introduced quantitative easing policies that led to massive capital outflows towards the middle-income countries. Brazil faced a tsunami of foreign exchange, which overvalued the currency and bred deindustrialization. Economic growth rates fell precipitously.

The government doubled its interventionist bets through public investment, subsidized loans, and tax rebates, which ravaged the public accounts. Their frantic and seemingly random interventionism scared away the internal bourgeoisie: the local magnates were content to run government through the Workers’ Party, but would not be managed by a former political prisoner who overtly despised them. And she despised not only the capitalists: the President had little inclination to speak to social movements, left organizations, lobbies, allied parties, elected politicians, or her own ministers. The economy stalled and Dilma’s political alliances shrank, in a fast-moving dance of destruction. The neoliberal opposition scented blood.

For years, the opposition to the PT had been rudderless. The PSDB had nothing appealing to offer while, as is traditional in Brazil, most mainstream parties were gangs of bandits extorting the government for selfish gain. The situation was so desperate that the mainstream media overtly (!) took the mantle of opposition and started driving the anti-PT agenda, literally instructing the politicians on what to do next. In the meantime, the radical left remained small and relatively powerless. It was despised by the hegemonic ambitions of the PT.

The confluence of dissatisfactions became an irresistible force in 2013. The mainstream media is rabidly neoliberal and utterly ruthless; the US equivalent would be Fox News and its clones dominating the entire US media, including all TV chains and the main newspapers. The upper middle class was their obliging target audience, as the members of that class had economic, social, and political reasons to be unhappy. Upper-middle-class jobs were declining, with 4.3 million posts paying between 5 and 10 minimum wages vanishing in the 2000s. In the meantime, the bourgeoisie was doing well, and the poor advanced fast: even domestic servants got labor rights. The upper middle class felt both squeezed and excluded from their privileged spaces, as was explained above. It was also dislocated from the state. Since Lula’s election, the state bureaucracy had been populated by thousands of cadres appointed by the PT and the left, to the detriment of “better educated,” whiter, and, presumably, more deserving upper-middle-class competitors. Mass demonstrations erupted for the first time in June 2013, triggered by left-wing opposition against a bus fare increase in São Paulo. Those demonstrations were fanned by the media and captured by the upper middle class and the right, and they shook the government — but, clearly, not enough to motivate them to save themselves. The demonstrations returned two years later. And then in 2016.

Now, reader, follow this. After the decimation of the state apparatus by the pre-Lula neoliberal administrations, the PT sought to rebuild selected areas of the bureaucracy. Among them, for reasons that Lula may soon have plenty of time to review, the Federal Police and the Federal Prosecution Office (FPO). In addition, for ostensibly “democratic” reasons, but more likely related to corporatism and capacity to make media-friendly noise, the Federal Police and the FPO were granted inordinate autonomy, the former through mismanagement, the latter becoming the fourth power in the Republic, separate from — and checking — the Executive, the Legislature, and the Judiciary. The abundance of qualified jobseekers led to the colonization of these well-paying jobs by upper-middle-class cadres. They were now in a Constitutionally secure position and could chew up the hand that had fed them, while loudly demanding, through the media, additional resources to maul the rest of the PT’s body.

Corruption was the ideal pretext. Since it lost the first democratic presidential elections, in 1989, the PT moved steadily towards the political center. In order to lure the upper middle class and the internal bourgeoisie, the PT neutralized or expelled the party’s left wing, disarmed the trade unions and social movements, signed up to the neoliberal economic policies pursued by the previous administration, and imposed a dour conformity that killed off any alternative leadership. Only Lula’s sun can shine in the party; everyone else was incinerated. This strategy was eventually successful and, in 2002, “Little Lula Peace and Love” was elected President. (I kid you not, reader: this was one of his campaign slogans.)

For years the PT had thrived in opposition as the only honest political party in Brazil. This strategy worked, but it contained a lethal contradiction: in order to win expensive elections, manage the Executive, and build a workable majority in Congress, the PT would have to get its hands dirty. There is no other way to “do” politics in Brazilian democracy.

We only need one more element, and our mixture will be ready to combust. Petrobras is Brazil’s largest corporation and one of the world’s largest oil companies. The firm has considerable technical and economic capacity, and it was responsible for the discovery, in 2006, of gigantic “pre-salt” deep sea oilfields hundreds of miles from the Brazilian coast. Dilma Rousseff, as Lula’s Minister of Mines and Energy, was responsible for imposing exploration contracts in these areas including large privileges for Petrobras. This legislation was vigorously opposed by PSDB, the media, the oil majors, and the US government.

In 2014, Sergio Moro, a previously unknown judge in Curitiba, a Southern state capital, started investigating a currency dealer suspected of tax evasion. This case eventually spiraled into a mortal threat to Dilma Rousseff’s government. Judge Moro is good-looking, well-educated, white and well paid. He is also very close to the PSDB. His Lavajato (Carwash) operation unveiled an extraordinary tale of large-scale bribery, plunder of public assets, and funding for all major political parties, centered on the relationship between Petrobras and some of its main suppliers — precisely the stalwarts of the PT in the oil, shipbuilding, and construction industries. It was the perfect combination, at the right time. Judge Moro’s cause was picked up by the media, and he obligingly steered it to inflict maximum damage on the PT while shielding the other parties. Politicians connected to the PT and some of Brazil’s wealthiest businessmen were jailed summarily, and would remain locked up until they agreed a plea bargain implicating others. A new phase of Lavajato would ensnare them, and so on. The operation is now in its 25th phase; many have already collaborated, and those who refused to do so have received long prison sentences, to coerce them back into line while their appeals are pending. The media turned Judge Moro into a hero; he can do no wrong, and attempts to contest his sprawling powers are met with derision or worse. He is now the most powerful person in the Republic, above Dilma, Lula, the speakers of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate (both sinking in corruption and other scandals), and the Ministers of the Supreme Court, which either have been silenced or quietly support Moro’s crusade.

Petrobras has been paralyzed by the scandal, bringing down the entire oil chain. Private investment has collapsed because of political uncertainty and an investment strike against Dilma’s government. Congress has turned against the government, and the Judiciary is overwhelmingly hostile. After years of sniping, the media has been delighted to see Lula fall under the Lavajato juggernaut, even if the allegations seem stretched: does he actually own a beachside apartment which his family does not use, is that small farm really his, who paid for the lake and the mobile phone masts nearby, and how about those pedalos? No matter: Moro detained Lula for questioning on 4 March. He was taken to São Paulo airport and would have been flown to Curitiba, but the Judge’s plan was halted for fear of the political fallout. Lula was questioned at the airport, then released. He was livid.

In order to shore up her crumbling administration and protect Lula from prosecution, Dilma Rousseff appointed Lula her Chief of Staff (the President’s Chief of Staff has ministerial status and can be prosecuted only by the Supreme Court). The right-wing conspiracy went into overdrive. Moro (illegally) released the (illegal) recording of a conversation between President Dilma and Lula, pertaining to his investiture. Once suitably misinterpreted, their dialogue was presented as “proof” of a conspiracy to protect Lula from Moro’s dogged determination to jail him. Large right-wing upper-middle-class masses poured into the streets, furiously, on 13 March. Five days later, the left responded with large — but not quite as large — demonstrations of its own against the unfolding coup. In the meantime, Lula’s appointment was suspended by a judicial measure, then restored, then suspended again. The case is now in the Supreme Court. At the moment, he is not a Minister, and his head is well positioned on the block. Moro can arrest him on short notice.

Why is this a coup? Because despite aggressive scrutiny no Presidential crime warranting an impeachment has emerged. Nevertheless, the political right has thrown the kitchen sink at Dilma Rousseff. They rejected the outcome of the 2014 elections and appealed against her alleged campaign finance violations, which would remove from power both Dilma and Vice-President — now, chief conspirator — Michel Temer (strangely enough, his case has been parked). The right simultaneously started impeachment procedures in Congress. The media has attacked the government viciously for years, the neoliberal economists plead for a new administration to “restore market confidence,” and the right will resort to street violence if it becomes necessary. Finally, the judicial charade against the PT has broken all the rules of legality, yet it is cheered on by the media, the right, and even by Supreme Court Justices.

Yet . . . the coup de grâce is taking a long time coming. In the olden days, the military would have already moved in. Today, the Brazilian military are defined more by their nationalism (a danger to the neoliberal onslaught) than by their right-wing faith, and, anyway, the Soviet Union is no more. Under neoliberalism, coups d’état must follow legal niceties, as was shown in Honduras in 2009 and in Paraguay in 2012.

Brazil is likely to join their company, but not just now. Large sections of capital want to restore the hegemony of neoliberalism; those who once supported the PT’s national development strategy have fallen into line; the media is howling so loudly it has become impossible to think clearly; and most of the upper middle class have descended into a fascist hatred for the PT, the left, the poor, and the blacks. Their disorderly hatred has become so intense, however, that even PSDB politicians are booed in anti-government demonstrations. And, despite the relentless attack, the left remains reasonably strong, as was demonstrated on 18th March. The right and the elite are powerful and ruthless — but they are also afraid of the consequences of their own daring.

There is no simple resolution to the political, economic, and social crises in Brazil. Dilma Rousseff has lost political support and the confidence of capital, and she is likely to be removed from office in the coming days. However, attempts to imprison Lula could have unpredictable implications, and even if Dilma and Lula are struck off the political map, a renewed neoliberal hegemony cannot automatically restore political stability or economic growth, or secure the upper middle class the social prominence that they crave. Despite strong media support for the impending coup, the PT, other left parties, and many radical social movements remain strong. Further escalation is inevitable. Watch this space.

Alfredo Saad-Filho, Department of Development Studies, SOAS University of London

Note to Commenters

Due to severe hacking attacks in the recent past that brought our site down for up to 11 days with considerable loss of circulation, we exercise extreme caution in the comments we publish, as the comment box has been one of the main arteries to inject malicious code. Because of that comments may not appear immediately, but rest assured that if you are a legitimate commenter your opinion will be published within 24 hours. If your comment fails to appear, and you wish to reach us directly, send us a mail at: editor@greanvillepost.com

We apologize for this inconvenience.

Nauseated by the

Nauseated by the

vile corporate media?

Had enough of their lies, escapism,

omissions and relentless manipulation?

Send a donation to

The Greanville Post–or

But be sure to support YOUR media.

If you don’t, who will?

Committing Crimes In Our Name.

![]() Past in Present Tense with Murray Polner

Past in Present Tense with Murray Polner

[dropcap]D[/dropcap]oes anyone remember James Kutcher, a victim of one of our Red Scares?

He was a badly disabled WWII veteran who belonged to the Socialist Workers Party, a miniscule and powerless Trotskyist group the U.S. government claimed was trying to overthrow it violently. As a result, he was fired in 1948 from his job as a Veterans Administration filing clerk.

Robert Justin Goldstein’s convincing, disturbing, and impressive new book, “Discrediting the Red Scare: The Cold War Trials of James Kutcher, The Legless Veteran” (Kansas) reminds us that Kutcher fiercely resisted the government, and finally won his battle. But for Goldstein, professor emeritus at 0akland University, the persecution and ultimate redemption of James Kutcher would be forgotten.

Robert Justin Goldstein’s convincing, disturbing, and impressive new book, “Discrediting the Red Scare: The Cold War Trials of James Kutcher, The Legless Veteran” (Kansas) reminds us that Kutcher fiercely resisted the government, and finally won his battle. But for Goldstein, professor emeritus at 0akland University, the persecution and ultimate redemption of James Kutcher would be forgotten.

But first, a few personal memories of that very dark era. My friend Lenny and I once watched two brave souls set up a stand on my neighborhood’s major shopping avenue and asked passers-by to sign their petition calling for support for the Bill of Rights. I have no idea whether they were serious or not, but very few, other than the two of us, signed, so pervasive was the fear. My sister’s high school steno-typist teacher, whose Marine son was killed in the Pacific, was accused of communist leanings and lost his job, a not unknown crime committed in our name in many of the nation’s public schools and universities. Another of our teachers, the humorist Sam Levinson (he taught Spanish and named his son Conrad after my sister’s fired teacher’s late Marine son), was threatened by the McCarran Senate subcommittee on Internal Security because of alleged Red connections and was rescued only after Dr. Abraham Lefkowitz, our school principal and well-known anti -communist in the city’s teacher wars, personally vouched for him. My gifted high school social studies teacher was fired by a frightened and spineless Board of Education. I was later told (though could never verify) that he went to work delivering milk. While I was a grad student at Columbia’s Russian Institute some of my classmates fantasized that FBI informers had been planted among us.

Nationally, it was a time of unforgiving and paranoid Torquemadas, loyalty boards, the Attorney General’s list of “subversive” organizations (the subject of Goldstein’s earlier book “American Blacklist”), the A and H-Bombs, Hiss, the Hollywood Ten, Hoover, the Korean War, McCarthy, Red Channels, HUAC, the 1949 Peekskill riot, more blacklists and book banning, an ugly period when everyone affected was seriously wounded. Years later, Michael Ybarra wisely pointed out in “Washington Gone Mad” that, while there were certainly communists in Washington, “it was the hunt for them that did the real damage.”

James Kutcher was drafted in 1940 in our first peacetime draft at age of 29. Assigned to the Infantry, he fought in North Africa, Sicily, and the Battle of San Pietro in Italy where a mortar shell cost him his legs. Hospitalized and then discharged after fitted for prosthetics, he was hired as a VA clerk but then dismissed because of his membership in the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party, whose leaders had been found guilty in 1943 for plotting “to use force to overthrow the government” — an absurd accusation.

(More about the tiny and toothless SWP may be found in my HNN reviews of Donna T. Haverty- Stacke’s “Trotskyists on Trial: Free Speech and Political Persecution Since The Age of FDR” and Said Sayrafiezadeh’s “When Skateboards Will Be Free: Memoirs of a Political Childhood”)

Relying in part on declassified FBI documents and the correspondence of contemporary lawyers, Goldstein reveals how the VA and Justice Department hounded and persecuted Kutcher and his parents who were also threatened with ejection from their Newark public housing apartment. The vindictiveness didn’t stop there when the government tried to deny him his disability pension. Even the “notoriously conservative American Legion” took exception to the firing, calling it an “almost perfect example of bureaucratic bungling,” notes Goldstein. Kutcher, they charged, was fired from a “little $40.00 a week clerical job” solely for “cheerfully” admitting his ties with an “insignificant sect.” Not everyone agreed with the AL, especially those on the Right.

The Communist Party also frowned on Kutcher’s fight. A west coast party paper, the Daily People’s World, rejected Kutcher’s claim. “What is being touted as the ‘case of the legless vet,’ they argued, and a case for civil liberties, hasn’t the remotest connection with the defense of civil rights.” In their twisted logic, the Communists insisted that while the government’s prosecution of their Stalinist party leaders violated their legal rights in no way did it do the same to Kutcher, a Trotskyist.

Even so, Kutcher had plenty of left and liberal supporters such as his invaluable pro bono lawyer, Joseph Rauh, writer Murray Kempton, civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph, philosopher John Dewey, architectural and urban critic Lewis Mumford, Norman Mailer, the CIO, Washington Post and especially Harold Russell, who lost his arms in the war and received an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his role in the 1946 film “The Best Years of Our Lives.” He and Kutcher had been roommates in Walter Reed Hospital, and Kutcher later told Russell that without the government granting him a fair trial “things will get as bad here as in Russia.”

Kutcher was relentless in his defense, traveling the country, one trip lasting nine months. He pleaded his case to Truman and Eisenhower, neither of whom answered. In his own book, “The Case of the Legless Veteran,” — which could not find an American book publisher other than SWP’s Monad/Pathfinder Press and later a documentary film was produced by someone else– Kutcher was elated, writing “that each administrative defeat, stripping away illusions about the intentions of the witch hunters, seemed to create new areas of interest and to open new avenues of support for us.”

Finally, after eight long years, several court rulings saw to it that his job and pension were restored and he and his family could remain in their apartment. But irony of ironies, the SWP expelled Kutcher and several hundred other members which, Goldstein tell us, was “following a change in leadership and policy in which Trotsky’s theory of permanent revolution” was discarded. The turn deeply upset Kutcher, who never abandoned his belief in socialism.

Still, the FBI would not let go. Goldstein discloses that after he was back at his VA job “the FBI continued to subject him to relentless surveillance.” In September 1956, the FBI put him on its Security Index, which Goldstein explains was “a listing of individuals who would be rounded up and detained without trial in the case of a national security emergency.” And in 1966, the FBI notified the Secret Service that Kutcher, still minus his legs, was “potentially dangerous.” The next year Goldstein discovered that Kutcher was included on the FBI’s “detcom” or “detention of Communists” list.

In the ensuing years, the SWP sued the FBI and won its fourteen-year case against the FBI and some intelligence agencies and were awarded $246,000. Federal Judge Thomas Griesa ruled that Hoover’s FBI –surprise!– had carried out investigations against “entirely lawful and peaceful political activities,” much as they had done in their Cointelpro program.

James Kutcher died in a VA hospital in Brooklyn in 1989 barely noticed in a country whose fundamental rights he had fought to preserve on the battlefield and then against his own countrymen and government. Goldstein laments: “In a final irony, Kutcher, who in life furnished the country with so many (often front-page) stories, was ignored in death. Not a single major paper mentioned his death or provided an obituary, with the exception of a tiny paid listing in the New York Times and a small obituary in New York’s Newsday.” Even so, I think Goldstein would surely agree, as I do, that the country owes much to James Kutcher for his courage in battling for freedom abroad and at home as well. I also wonder if Kutcher’s experience is also a cautionary tale of what could lie ahead in our never-ending War on Terror.

Of related interest is this documentary: The Case of the Legless Veteran: James Kutcher (Directed and produced by Howard Petrick)

Contributing Editor, Murray Polner wrote “No Victory Parades: The Return of the Vietnam Veteran“; “When Can I Come Home,” about draft evaders during the Vietnam era; co-authored with Jim O’Grady, “Disarmed and Dangerous,” a dual biography of Dan and Phil Berrigan; and most recently, with Thomas Woods,Jr., ” We Who Dared to Say No to War.” He is the senior book review editor for the History News Network.

Contributing Editor, Murray Polner wrote “No Victory Parades: The Return of the Vietnam Veteran“; “When Can I Come Home,” about draft evaders during the Vietnam era; co-authored with Jim O’Grady, “Disarmed and Dangerous,” a dual biography of Dan and Phil Berrigan; and most recently, with Thomas Woods,Jr., ” We Who Dared to Say No to War.” He is the senior book review editor for the History News Network.

ALL CAPTIONS AND PULL-QUOTES BY THE EDITORS, NOT THE AUTHORS.

Note to Commenters

Due to severe hacking attacks in the recent past that brought our site down for up to 11 days with considerable loss of circulation, we exercise extreme caution in the comments we publish, as the comment box has been one of the main arteries to inject malicious code. Because of that comments may not appear immediately, but rest assured that if you are a legitimate commenter your opinion will be published within 24 hours. If your comment fails to appear, and you wish to reach us directly, send us a mail at: editor@greanvillepost.com

We apologize for this inconvenience.

Nauseated by the

Nauseated by the

vile corporate media?

Had enough of their lies, escapism,

omissions and relentless manipulation?

- Share our articles widely

- Join the mail list

- Donate what you can.

But be sure to support YOUR media. If you don’t, who will?

![]() =SUBSCRIBE TODAY! NOTHING TO LOSE, EVERYTHING TO GAIN.=

=SUBSCRIBE TODAY! NOTHING TO LOSE, EVERYTHING TO GAIN.=

free • safe • invaluable

[email-subscribers namefield=”YES” desc=”” group=”Public”]

War Diary: Texac Reminisces about His First New Year’s Day in Donetsk

= War Diary by Russell “Texac” Bentley =

My First Battle, Troishka, New Year’s Day 2015

Our correspondent Russell Bentley has been filing his dispatches from Donetsk for over a year now. In the process, and chiefly due to the fact he often does his writing literally from the frontlines of the war in Eastern Ukraine, as a regular soldier in the Novorossyian Armed Forces (NAF), the priorities in the publication of his materials have sometimes shifted. This is a report filed by him about one year ago, and subsequently modified. Passages may have been published before. But what he has to say—as always— remains relevant, fresh, and inspiring. —PG

Our correspondent Russell Bentley has been filing his dispatches from Donetsk for over a year now. In the process, and chiefly due to the fact he often does his writing literally from the frontlines of the war in Eastern Ukraine, as a regular soldier in the Novorossyian Armed Forces (NAF), the priorities in the publication of his materials have sometimes shifted. This is a report filed by him about one year ago, and subsequently modified. Passages may have been published before. But what he has to say—as always— remains relevant, fresh, and inspiring. —PG

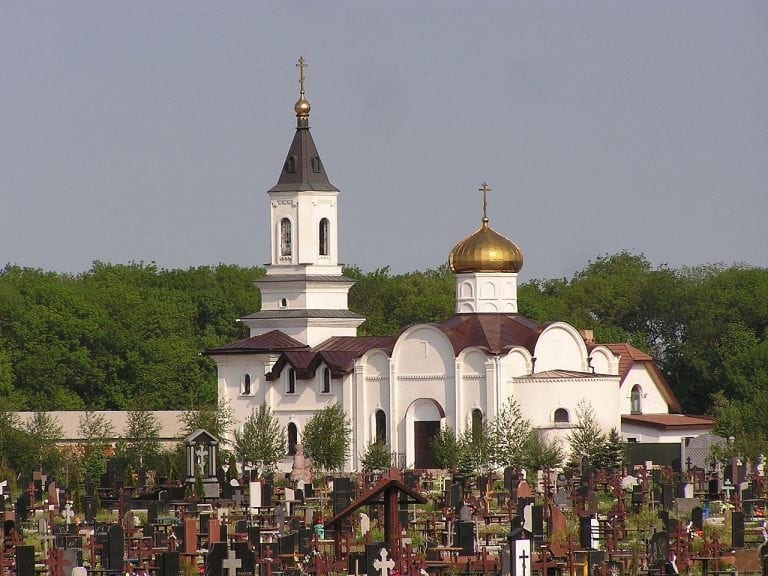

I woke up on New Year’s Day 2015 without a hangover though the night before I had drunk some champagne and a fair amount of vodka. Not a lot, but about as much as I would have drunk on a regular NYE back in the States. I was always pretty careful in that respect, I never got a single DWI. But I didn’t wake up back in the States, I woke up in a convent in the middle of a graveyard in Southeast Ukraine that was a major battlefield in the opening salvos of the Third World War.  Inside my sleeping bag, I was fully clothed in the Russian Army winter fatigues I had bought, along with the sleeping bag, in Rostov before crossing the border into Novorussia. Disrobing for sleep the night before had consisted of removing my boots, steel Class IV armored vest and kevlar helmet and hanging my AK-74 on a hook with my webgear. Across the room from me, in the frozen pitch black darkness, snored the two Italian volunteers, Spartak and Archangel. Below me, Lataishik, the sniper, and in the bunk next to his, Bielka, the PKM machine-gunner. Above them, the only guy on a top bunk, lay Texas, the New Kid on the Block, who wasn’t from anywhere around there. That would be me, your humble narrator…

Inside my sleeping bag, I was fully clothed in the Russian Army winter fatigues I had bought, along with the sleeping bag, in Rostov before crossing the border into Novorussia. Disrobing for sleep the night before had consisted of removing my boots, steel Class IV armored vest and kevlar helmet and hanging my AK-74 on a hook with my webgear. Across the room from me, in the frozen pitch black darkness, snored the two Italian volunteers, Spartak and Archangel. Below me, Lataishik, the sniper, and in the bunk next to his, Bielka, the PKM machine-gunner. Above them, the only guy on a top bunk, lay Texas, the New Kid on the Block, who wasn’t from anywhere around there. That would be me, your humble narrator…

IT WAS PITCH DARK, totally dark, and it was freezing. The temp was not so bad as long as I only stuck my nose out of the bag. The bag itself was rated for the Arctic, and that, along with my heavy Russian uniform, kept me pretty warm. Except for my nose. The windows were filled with sandbags, to the point that they were almost airtight. They were certainly light tight, and pretty good protection against bullets and artillery shrapnel, which was the main idea. The doors were covered, inside and out by heavy rugs nailed in place over the doors. They too were pretty much airtight. The walls of the building were almost 18 inches thick, including the interior walls and doorways. Airtight, light tight, freezing cold, it was almost like being in a crypt. The only difference was I had to take a piss.

I reached around and felt for my flashlight. Besides guns, food and bullets, a flashlight is one of the most important things you can have at the Front. I’d been in some pretty primitive situations before, and I had an idea about what to bring. I brought three. Two were the kind you wear on your head, and another handheld that could be charged by cranking. I found the one I was feeling around for and turned it on. The wood stove below me was cold and dark. I climbed down and lit a candle, the only source of illumination, besides flashlights. Since I was going outside to piss, I donned my steel vest and grabbed my Kalash. I walked to the end of the hallway and walked down the stairs. There were a few openings in the windows on the first floor, and the dim light of dawn filtered through. Which meant the snipers could see me.

Our position, our building, faced enemy positions on two sides – to the North, straight ahead, the Donetsk Airport control tower raised its head like a ragged viper, 400 meters away. About halfway between was a woodline that was the launching site for the almost daily Ukrop attacks. To the right, to the West, in the direction of Freedom and Prosperity, the New Terminal of the Donetsk Airport was held by the “Cyborgs” a supposedly elite unit of the Ukrainian Army, backed by Pravy Sektor Nazis and Western mercenaries. Our toilet was a small building about 50 meters across open ground, covered by Ukrop sniper fire from the control tower. I asked the guy on guard duty (in sign language, of course) if that was where I had to go to piss. It turned out that I could piss on the floor in one of the downstairs rooms, it was only if I had to take a shit that I’d have to brave the sniper fire. I decided to try that later, and settled for a piss.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]hat morning it occurred to me that I was among true Freedom Fighters, men who were defending their own homes and families from foreign invaders who were bent on nothing less than enslavement of the locals. These men were not “defending freedom” by going to a foreign country and shooting people there, they were defending their own freedom, literally in their own backyards, and doing it quite well. We faced 150 infantry, Pravy Sektor and Regular Army, armor and artillery, including Grads (rocket batteries). There were never more than 20 of us there at once, usually a lot less. Firefights every night, and almost every day. Thousands of rounds, each way. Artillery every few days, fifty to a hundred rounds, incoming. But we held our own.

I returned upstairs, where things were starting to stir. The first stove to be lit was in the kitchen. Ammo crates were the preferred firewood, and the majority of what we had to burn. Coffee, nyet, but there was tea, “chai” black and strong, with too much sugar. Breakfast was the leftover potato soup from the night before. As the morning progressed, I began to interact with my comrades, and take stock of them, and them of me. The two combat commanders were Reem and Mir (“Chrome” and “Peace”.) The following equation may not make sense to the civilians or mathematicians among us, but combat vets will know what I mean – Reem was worth any 10 regular soldiers, and Mir was worth 5, but together they were worth 30, and there were plenty of times when 30 Ukrops were scared to go up against just those two. They ran the “Utes”, and they ran it heavy. The Utes is a heavy machine gun, equal to the US M-2 50 cal. Reem was the gunner, and Mir was his sideman and spotter. Reem was a big man, but he seemed even bigger. Mir was a short guy, but the scarier of the two.

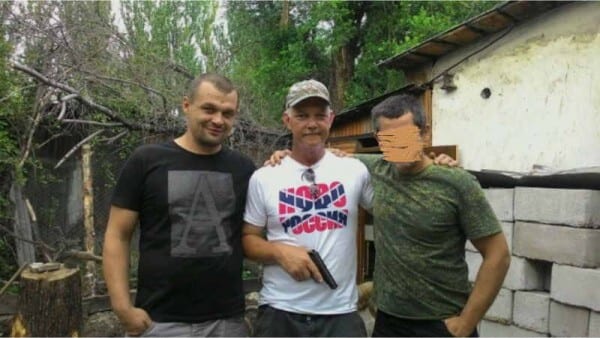

“Reem” means “Chrome”, and “Mir” means “Peace” or “Earth”. (Mir’s face blurred for the safety of his family, which still resides in Kiev controlled territory).

Reem didn’t say much, and everything that Mir said to me seemed somehow tinged with a threat. When Mir told me he was a dentist, I figured he really meant “dentist” in the mafia sense – he knocked people’s teeth out with his fists for a living. He wasn’t the kind of guy who needed pliers. That evening, over dinner, Mir peppered me with questions, what I knew about Russian history, Russian culture. Well, I knew a bit. Come and See by Elim Klimov, Eta Vso by DDT. The Sacred War. Reem just sat back and listened. He didn’t say much, but like E. F. Hutton, when Reem talked, everybody listened. I did too, of course, but the only difference was I couldn’t understand anything he said. He was that kind of guy, a big, dark Russian with a rumbling voice like the sound of distant artillery that was slowly coming closer. He could say “Merry Christmas” and it would sound like the voice of impending doom. But I could tell he liked me, even if I was pretty sure Mir didn’t. After dinner, Mir invited me back to the Commander’s Room, at the suggestion of Reem. Of course, I went.

Each room, including the Commander’s, had two double bunks on the North and South walls, for a total of 8 bunks in each room, usually with 4 or 5 soldiers in each. Candles were the only illumination, but Reem’s stove worked better than most, and the room was actually warm. We sat down for some Green Tea.

We had some tea, a Russian tradition that while not as formal as the Japanese ceremony, had its protocols. I sat in a dark room, lit by a single candle and listened to Reem give combat instructions to the other 3 soldiers who were there, then he turned to me and made me understand it was time to fight. The Ukrops would start their attack within the next 10 minutes. I was to got to my room, don my vest, helmet and webgear with 4 loaded magazines and be ready to work. In Russian military circles, the word “robota”, “to work”, means to start shooting. I did as I was told. In my room, I paused for a moment to say a prayer, then donned my gear and reported to the guys who were setting up near the Utes at the front of the building, facing the control tower. I was instructed to take a firing position on the 3rd floor, along with Arik the sniper. It was about 8PM, and a light snow had started to fall. We took up our position just as the Ukrops began to open fire.

SIDEBAR READ BELOW ABOUT THE MONASTERY TURNED INTO AN STRATEGIC POST WHERE TEXAC WAS STATIONED WITH HIS COMRADES

Sidebar Ends Here

Sitting there, warmed by a wood stove, lit by a candle, listening to the soft, deep and ominous rumble of Reem’s voice, I felt about as far away as it was possible to be from the conventional reality of my friends and family back in the States. I was living like an outlaw cowboy from the 1800’s, but I was doing so in Eastern Europe in the 21st Century. It was crazy, it was weird, it was hard and it was scary, but there was no place on Earth I would rather have been.

We had some tea, a Russian tradition that while not as formal as the Japanese ceremony, had its protocols. I sat in a dark room, lit by a single candle and listened to Reem give combat instructions to the other 3 soldiers who were there, then he turned to me and made me understand it was time to fight. The Ukrops would start their attack within the next 10 minutes. I was to get to my room, don my vest, helmet and webgear with 4 loaded magazines and be ready to work. In Russian military circles, the word “robota”, “to work”, means to start shooting. I did as I was told. In my room, I paused for a moment to say a prayer, then donned my gear and reported to the guys who were setting up near the Utes at the front of the building, facing the control tower. I was instructed to take a firing position on the 3rd floor, along with Arik the sniper. It was about 8PM, and a light snow had started to fall. We took up our position just as the Ukrops began to open fire.

One of the first things you learn, instinctively and without instruction, is to tell the difference between bullets being fired in your general direction and bullets being fired directly at you. The latter have a distinctive “crack!”, a mini-sonic boom as they pass, or else you can hear their impact on whatever cover you happen to be using for protection. The tempo and intensity of fire from the Ukrops quickly increased. There were at least 3 separate groups in the woodline, 150 meters to our front – one on the left and two to the right. Probably between 12 and 20 soldiers, laying down a steady stream of fire. …It was a surreal existence, dark, cold, deadly danger. In a strange language. Operating mostly on vibes. They’d look at me and tell me something important, and I’d have absolutely no idea what the words they’d just said meant, but I could catch the vibe. And I have to say I caught on pretty quick. It only took me two days to figure out I was wearing my body armor backwards. Russians don’t teach you, they let you figure it out. And we all had a good laugh when I did. The trick to doing everything the right way, the best way it can be done, is to do it like they do.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap] reloaded my mags as quickly as I could, and learned many important lessons in the process. Often, in battles at Troishka, both sides would need to reload at pretty much the same time. Being able to reload quickly is as important as being able to unload accurately. I was pretty slow that first night, but soon learned to get much, much better. I returned to the window where Arik was still working, and took up my firing position. I fired a round, then pulled the trigger again. Nothing happened. I looked down at my rifle and saw the bolt was jammed in a half open position. I tried pushing forward and pulling back, but it was stuck. Fuck… The Kalashnikov series of rifles are among the best combat weapons ever produced, and their superior quality has always been their reliability. I thought that either a Ukrop bullet had hit my rifle, or a bad bullet had exploded in the chamber. I went downstairs, not relishing the idea of sitting out the rest of the raging firefight with an inoperable weapon. I showed my rifle to Mongoose, the commander. He also tried to get it to function, to no avail. So he gave me an RPK that was in the arms room, and I continued the fight with that. The battle continued for several hours, until the Ukrops finally withdrew back to the control tower complex. We gathered in the arms room to reload and to smoke cigarettes. It was about midnight, and it had been a long night. I left my AK in the arms room, and took the RPK with me to my bunk. I removed my webgear, helmet, boots and vest, and crawled up onto my bunk. The room was still of course freezing cold, no fire in the stove, only a candle for illumination. I slid into my bag, said a prayer of thanks, and went to sleep, with only my nose sticking out. Tomorrow would be another busy day.

The Kalashnikov series of rifles are among the best combat weapons ever produced, and their superior quality has always been their reliability. I thought that either a Ukrop bullet had hit my rifle, or a bad bullet had exploded in the chamber. I went downstairs, not relishing the idea of sitting out the rest of the raging firefight with an inoperable weapon. I showed my rifle to Mongoose, the commander. He also tried to get it to function, to no avail. So he gave me an RPK that was in the arms room, and I continued the fight with that. The battle continued for several hours, until the Ukrops finally withdrew back to the control tower complex. We gathered in the arms room to reload and to smoke cigarettes. It was about midnight, and it had been a long night. I left my AK in the arms room, and took the RPK with me to my bunk. I removed my webgear, helmet, boots and vest, and crawled up onto my bunk. The room was still of course freezing cold, no fire in the stove, only a candle for illumination. I slid into my bag, said a prayer of thanks, and went to sleep, with only my nose sticking out. Tomorrow would be another busy day.

The days and nights consisted of taking care of day to day chores while waiting, and being ready, to be attacked by numerically superior forces at any time. We usually had about 5 minutes warning, from radio intercepts or observation that the attack was coming in the next few minutes, or some Ukrop would open fire early, and let us know they were coming. When we hit back, it was hard. Reem and Mir were on the Utes heavy machine gun, and we had an AGS automatic grenade launcher, plus maybe 10 or 12 more guys with rifles. Plenty of ammo. Supplies were delivered every day or so, water, food, ammo. At dawn the car or van would arrive, 3 or 4 of us would run across the open terrain to the relative cover in front of the church. And back with heavy burdens, two or three trips. Firewood was a rarity, though there was a big pile of wooden construction debris about 300 meters away, across sniper scanned fields. And we went and got it there too. Nobody got hit, but in retrospect, it seemed crazy. No matter. Within a few days of my arrival, we were shooting so much ammo we had plenty of wooden ammo crates to burn. Plenty.

One night, I was assigned to AGS duty. The AGS is a machine gun that shoots grenades that will cut any exposed meat within a 5 meter radius of where they hit. But totally ineffective against armor. As the nightly Ukrop attack began, Lataishik, Mas and I unsheathed the monster and prepared for battle. It was pitch dark, and I couldn’t see a thing. We couldn’t use our flashlights because light draws fire, so it was literally touch and go. Lataishik let off about 5 rounds and then turned to me and said “Te agon”, “You shoot”. I felt my way over and went ahead and did. All the while, bullets are impacting within a foot or two of the edge of the window we are firing out of. You just have to ignore them and keep on working. When they shoot at you, you can see the muzzle flash from the rifles. Then you know where to shoot back with a grenade machine gun. I laid some down. I had learned from Mir on the Utes that you never shoot the same target twice, a different one every time, every few seconds, so they never know if the next one’s for them. We ran through six 25 round drums, then it was time to reload. Quickly, because the battle was not over.

[dropcap]L[/dropcap]ataishik assumed sniper duty at the window with his SVD. Mas and I headed up to the ammo room to reload. Reloading AGS belts, under optimum conditions is not an easy task. Barehanded in the freezing dark, for the first time, in the middle of a battle, I have to rate as among the toughest things I have ever done. And that’s how it went. OJT, On the Job Training, but I was catching on. I hadn’t gotten killed yet, or gotten anyone else killed, so I was doing pretty good. I did my share of guard duty – on the stairs by the AGS, guarding the entrance against “surprise visitors” in the form of Pravy Sektor commandos stationed half a kilometer away. The other guard post, manned 24 hours a day, was the PKM window beside the Utes. We had a night vision (light amplification) scope for the Utes, and a handheld thermal imager for observation. Beyond bullets, beyond Grads, my biggest fear was that I would drop the thermal imager on guard duty. I t was one of our most important weapons. Technically, “Non-lethal”, but it multiplied the power of every weapon 20 times, because it could show us where to shoot. Remember that when US government hacks talk about non-lethal aid. Some of the most important weapons in war cannot kill people by themselves.

THE BATTLES OCCURRED WITH REGULARITY, pretty much every day, and every night. Battles lasted at least an hour, sometimes many hours, with literally thousands of rounds fired by each side. One night, Mongoose was at the next position, Milnitsa, (“Windmill”) meeting with other commanders when the Ukrops attacked Troishka. It was a heavy battle, and we soon needed to reload. Unfortunately, Mongoose had the key to the main ammo room, and fire was too heavy for him to make his way back. It was not a pleasant situation – We were literally running out of bullets for all our weapons, and it wouldn’t take the Ukrops and Pravy Sektor nazis long to figure it out. 150 meters across semi-open ground, and they would be at the door. We would be fighting with knives against psychos with loaded machine guns.

Fortunately, Orion, who had arrived a few days after me, came up with a solution, not elegant, but effective – a wood-splitting maul makes a passable field expedient door key when your life is on the line, and within minutes, the door was in splinters, and we were opening ammo cans and reloading mags and ammo belts as if our lives depended on it. Which, of course, they did. Reloading is as important a skill as shooting. There are tricks to it, as with everything here. When you’ve loaded up all your mags, you take a big handful of loose rounds and put them in the right hand pocket of your coat. Not the left side pocket, because then you have to transfer every round to the right hand before you put it in the mag, and it takes almost twice as long to re-load. With our mags topped off, we suddenly began returning heavy fire towards the Ukrops who were advancing, much to their surprise and dismay. We owed a debt of thanks to Orion, and after the battle, we all gave him a pat on the back.

Each day was like a week, and filled with learning experiences. I was promoted to a front firing position, to the right of the Utes, my “office” with a small firing port that had been chipped out of the wall. I often shared my office with Mars, the top sniper in the Essence of Time combat unit and one of the best snipers in the NAF.

I was asked if I wanted to train as a sniper, but declined. Sniper is a young man’s job, and I was a bit old, and my eyesight was not quite up to snuff. I was pretty good with the Kalashnikov and PKM, but was reluctant to take up the sniper’s SVD. The war continued…

On the 12th of January, Motorola and Spartak Battalion moved into the Cachigarka position under heavy fire. Cachigarka is halfway between Troishka and the New Terminal. That evening, the Utes was moved from it’s usual position to a window facing New Terminal. We were given a warning order that Sparta would assault the New terminal that night, and we would provide covering fire for their approach.

At 22:00 Hours (10 PM) the attack began. The entire New terminal was lit by muzzle flashes and incoming tracers. Mortar and artillery fire was constant. It was an important engagement with more than a hundred soldiers on each side. As Sparta entered the Terminal on the left, we were instructed to shift our fire to the right end of the Terminal. At about 1 AM, a magazine of green tracer was fired straight up into the air, the signal that the New Terminal had been taken. It was a major victory for the NAF. At 4 AM, I was posted to guard duty at the door. In the last few minutes of my 3 hour shift, exhausted, I started to doze off, only to awaken moments later to Mars standing above me on the stairs, understandably very angry. I would be assigned “robot duty” as punishment for my infraction. Orion would also be joining me. Under artillery attack the night before, he was reporting to Milnitsa, and was saying over open radio frequencies that Ukrop rounds were landing “300 meters to our left.” As Mars pointed out, he was inadvertently acting as an artillery spotter for the Ukrops. So, the next day, Orion and I made our way under intense artillery fire to the Gavin position.

![]() [dropcap]T[/dropcap]hey had a basement there that was to be used as a bomb shelter, but was filled with junk, old food and other miscellaneous debris. Our job was to clean the basement. Although it was a punishment mission, the weather was clear and not too bitterly cold, and we were several hundred meters back from Troishka, in relative safety. It was almost a holiday. We spent a few hours working hard to clear out the basement, then lounged around in the sunlight and clean, crisp, smoke-free air. While we were there, Somali Brigade brought up several tanks and began a sustained fire attack on the control tower. Just after lunch, it was cut down. The ukrops still held the buildings in the control tower complex, but had been deprived of an important observation post, at the probable cost of several of their lives. Another major victory for us. We were kickin’ ass and taking names…

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]hey had a basement there that was to be used as a bomb shelter, but was filled with junk, old food and other miscellaneous debris. Our job was to clean the basement. Although it was a punishment mission, the weather was clear and not too bitterly cold, and we were several hundred meters back from Troishka, in relative safety. It was almost a holiday. We spent a few hours working hard to clear out the basement, then lounged around in the sunlight and clean, crisp, smoke-free air. While we were there, Somali Brigade brought up several tanks and began a sustained fire attack on the control tower. Just after lunch, it was cut down. The ukrops still held the buildings in the control tower complex, but had been deprived of an important observation post, at the probable cost of several of their lives. Another major victory for us. We were kickin’ ass and taking names…

I had picked up a bad lung infection in training at Ysynavada, and I continued to have a serious cough. During my weeks at Troishka, it had not gotten any better. It could not have gotten any worse, because it was already as bad as it could get. The frigid temperatures and dense smoke that were ever-present did not help any, either. It was really bad, but not bad enough for me to ask to go to the hospital. I had not come to Donbass to check into a hospital of my own volition. But on the 14th of January, the Vostok Battalion doctor came to Troishka to visit me. He asked many questions, listened to my chest and noted the lung-crushing conditions of smoke and cold. He did his best to talk me into coming back with him, but I refused. I did not intend to leave before my comrades did. But the next evening, having green tea with Reem, a message came over the radio – I was ordered to be ready to move to the hospital the next morning at dawn, and to leave when the supply van departed. Conditions were very harsh, and honestly, I was very sick, but I was more dismayed than relieved by the order. In my rudimentary Russian, I conveyed to Reem that I did not want to go and had not asked to. He understood.

At dawn on the 16th of January, I bid my comrades good luck and boarded the van back to civilization. After a little over two weeks in heavy combat, my entire perspective on life had changed, and I finally had a realistic idea about what my new life was really going to be like. As the van made its way from combat zone to city center, it was like going from one world to another, though separated by only a few thousand meters. At the Vostok hospital, I was prescribed 4 days of bed rest. Rather than stay at the hospital, I prevailed on my doctor to allow me to stay ay the apartment of my friend Christian Malaparte. Ti was warmer and more comfortable, the food was better and most of all I could communicate in English. Between basic training and combat at Troishka, it had been over a month without a single day off, without a doubt, the hardest month I had ever spent in my life. I was ready for a little R&R, and felt I deserved it. I got to Christian’s apartment, was fed royally, chugged down most of a bottle of Armenian cognac and passed out for the next 16 hours. Meanwhile, back at the airport, Troishka was about to become the scene of one of the biggest and most important battles of the war…

ADDENDUM

Days of war and comradeship…la lotta continua.

The battle of Donetsk Airport was one of the earliest and fiercest encounters of this war.

This is our salute to the heroic defenders of this important position.