‘Disgraceful!’ exploded the parliamentarian.

What appalled British MP Daniel Kawczynski was that his country was about to cancel a $8.4-million deal to modernize Saudi Arabia’s prison system amid concerns about the country’s worsening human rights.

A betrayal, in the eyes of Kawczynski, the Conservative member who has chaired the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Saudi Arabia.

And up to then, last October, such an event was virtually unheard of. Saudi Arabia is our friend, is the mantra that has for decades rung out from corridors of power in Britain, the US, Canada and Australia.

Never mind the public executions, the medieval floggings, lack of even the most basic rights for women. Never mind that citizens of this oil-rich Gulf state have their daily lives controlled by brutal secret and religious police, and a legal system based on regal whim rather than rule of law. Or that Saudi Arabia is one of the world’s last remaining absolute monarchies and effectively a dictatorship. Or that it produced most of the 9-11 terrorists. 1

Saudi Arabia is our friend.

Security smoke and mirrors

If you believe the British government, it’s all about keeping safe: ‘The reason we have the relationship is our own national security,’ said David Cameron recently. ‘There was one occasion since I’ve been prime minister where a bomb that would have potentially blown up over Britain was stopped because of intelligence we got from Saudi Arabia… For me … our people’s security comes first.’2

It’s also conveniently secret. There exists a Memorandum of Understanding between Britain and Saudi Arabia on security. But despite a number of Freedom of Information requests, we are not allowed to know its contents. Australia too has a secret pact.’3,4

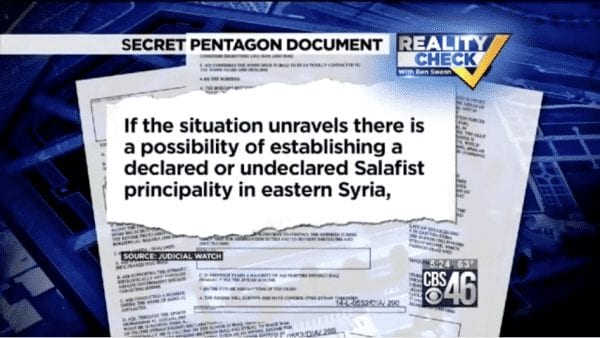

US Secretary of State John Kerry recently confirmed his country’s ongoing support for Saudi military intervention in Syria and in Yemen. ‘We have made it clear that we stand with our friends in Saudi Arabia.’5 Canada’s Minister for Foreign Affairs, Stéphane Dion, recently described Saudi Arabia as ‘an important partner in efforts to counter terrorism [and] to find a political solution in Syria.’6

Oil, guns and money

Something else underpins the special relationship. It’s been called ‘the prosperity agenda’.

Historically Saudi’s prodigious quantities of cheap oil helped power Western economic growth. Today, other fuel sources, such as shale, are being developed and, hit by falling oil prices, Saudi petrol revenue is not what it was.

But that has not affected the kingdom’s legendary spending on weapons. In 2014 it became the world’s biggest buyer.7 In 2015 it was expected to purchase $9.8 billion worth of weaponry, boosting the profits of the US, British, French and Canadian arms industries especially. Saudi Arabia’s intervention in Yemen as well as Syria produced more orders in the past year, $1 billion worth of US bombs alone between July and September.8

With its undiversified economy, Saudi is a big importer of goods and services in general. Beef, barley and passenger vehicles from Australia; food, healthcare and engineering from New Zealand/Aotearoa.9,10 The kingdom provides thousands of well-paid jobs for Western expats. Canadian universities recently caused a storm at home by undertaking to set up men-only branches in Saudi Arabia.11

Rich Saudi princes and business owners (often the same thing) are valued customers of financial services in London and New York. Extra secrecy can be made to prevail. For example, you can find out how much sovereign debt China holds in US dollars. Saudi’s holdings are a state secret, both in the US and the kingdom.12

The Saudi ambassador to London, Mohamed bin Nawwaf bin Abdulaziz, was less coy when he wrote an open letter complaining about negative attitudes displayed towards his country in parliament and in the media. He valued Saudi ‘private business investments’ in the country at $128 billion.13

The tremendous wealth of the Al Saud dynasty secures the soft power of cultural influence too. Oxford University, SOAS and the London School of Economics are among many recipients in Britain; Melbourne, Griffith and University of Western Sydney in Australia; while in the US, Yale Law School recently received $10 million from a Saudi donor.14,4

Saudi cash flows into new mosques and community centres; one estimate suggests that $100 billion has been spent promoting hardline Wahhabism abroad.15

But perhaps the most egregious bit of influence peddling occurred in the UN, when the British and Saudi Arabian governments agreed to swap votes to ensure that Saudi got a place on the influential UN Human Rights Council, which it now chairs.16

Changes at the top

For decades Saudi Arabia attracted only occasional interest from the international media.

Then, in early 2015, King Abdullah died and was succeeded by his 79-year-old brother Salman. It soon became clear that it was not the ailing Salman who was in charge, but his photogenic 29-year-old son, Mohammad bin Salman, acting as both Defence Minister and Deputy Crown Prince. He is variously described as a ‘pop idol’ prince – a hit with young Saudis – and ‘the most dangerous man in the world’. Unlike many Saudi princes he was educated not abroad but within the kingdom.

In March, MbS (as he is known) ordered the bombing of neighbouring Yemen, in a bid to oust Shi’a Houthi rebels and to reinstall the Sunni former leader Abd Rabbuh Mansour Hadi. Estimated to have cost 6,000 lives, the heavy bombardment of civilian targets (including hospitals) has produced near-famine and brought condemnation from international charities and human rights groups.

Under King Salman’s rule, repression within Saudi Arabia has intensified too; executions in 2015 were the highest in 20 years. Then early this year, 47 ‘terrorists’ were executed in one day, including the prominent Shi’a cleric Nimr al-Nimr. This provoked outrage within Shi’a communities across the world, but especially Iran, where protesters set fire to the Saudi embassy in Tehran.

The effect of the Iranian reaction has been to rally Saudi’s Sunni majority population around a leadership that is adept at exploiting sectarianism for political gain.

Saudi Arabia’s Shi’a population have long been discriminated against. Economically marginalized, they are excluded from positions of state. Saudi children are taught in school that Shi’a are non-believers. The regime claims that Saudi’s Shi’a communities are loyal to Iran, though experts say there is little evidence of this.

Selling arms to Saudi Arabia does not keep anybody safe. It increases the risk of terror attacks and worsens the refugee crisis

Safa Al Ahmad, who made a film about the 2011 protests in her home town of Qatif calling for the release of political prisoners, says that the mood in Shi’a communities today is one of fear: ‘The executions came as a shock. There are over 300 political prisoners. People are thinking: will they now go ahead and execute people like crazy? What will stop them? There was such a lot of high-level involvement [internationally] to stop this happening and it made no difference.’

She adds: ‘It seems the government is not interested in a political solution. In the past, someone from the government would try and reach out to the people of the Eastern Province, would make an appearance. That is not the case now.

‘The decision-making is in a far tighter circle than it used to be. Many more people used to be involved before and knew what was going on.’

Saudi social media is abuzz with rumours of strife within the royal family, centring on MbS.

While talking to The Economist about his plans for a neoliberal overhaul – including privatization of the state oil company, ARAMCO – the king’s son sounded like he was taking sole charge of the economy too.17

A kingdom in trouble

[dropcap]B[/dropcap]ehind Saudi Arabia’s more aggressive stance is fragility. The Saudi economy is in trouble. This year it faces a $98-billion budget deficit.18 The oil price has collapsed – slipping to below $30 a barrel. For its existing budget to work, Saudi needed a price of $100 per barrel. Austerity measures have begun. These are anxious times for a regime used to throwing money at all problems.

The war in Yemen is costing Saudi Arabia $6 billion a month, with the Houthis showing little sign of giving up.19 The West’s recent rapprochement with Iran and lifting of sanctions has rattled Riyadh. It must be galling for the Al Saud, given the years and billions spent on buying the West.

Then there is the threat posed by Islamic State. Last year saw 15 attacks by IS militants on Saudi soil, including one on a Shi’a mosque killing 23 people. Self-acclaimed IS caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi has vilified the Al Saud, calling them hypocrites who are betraying Islam.20 It’s ironic: the ruling family owes its legitimacy to the puritanical form of fundamentalist Islam called Wahhabism and uses it to maintain its power. But both al-Qaeda and, now, Islamic State are the ideological products, the natural offspring, of Saudi Wahhabism.21

The Saudi regime is often accused of funding terrorism, if not directly at least ideologically or through its mosques. IS is a proscribed organization in Saudi Arabia and it’s illegal for Saudi nationals to go abroad to fight for it. But how much public support exists is hard to tell. A 2014 survey showed about five per cent of Saudis supporting IS, but after the Paris attacks, Saudi Arabia was the overwhelming source of tweets siding with the killers.20,22

According to Saudi expert Toby Matthiesen: ‘Saudi Arabia is particularly vulnerable to Islamic State because their ideologies are very similar; a lot of people in the country sympathize with its broader aims, especially its anti-Shi’a, anti-Iran stance. It’s a double-edged sword. The government has been stoking this anti-Shi’a fire for a long time and people believe it. Then, here comes a group whose aim is to kill all the Shi’a and there are people who think this is a good idea.’

Meanwhile, the announcement by the Defence Minister that the kingdom was to lead a coalition of 34 Muslim states to fight terrorism is dismissed by most – including some of those named – as a publicity stunt. The coalition, significantly, did not include either Shi’a-led Iraq or Iran.

So the idea that Saudi Arabia is a reliable ally for the West rests on some pretty shaky assumptions: that Saudi Arabia is maintaining stability in the region; that it is genuinely committed to cracking down on Islamist terrorism; and that it is ideologically capable of doing so.

What can the West do?

Stop supplying arms for a start. Belgium and Sweden have, respectively, refused and cancelled lucrative sales.23

Following a damning UN report, showing that civilians are deliberately targeted and starved by the Saudi coalition in Yemen, the Canadian government is under increased pressure to justify its $15 billion armoured vehicles deal.24 In the US, senators are demanding greater oversight on arms sales to Saudi Arabia.25 In Britain, a cross-party group of MPs is calling for a suspension, while, at the time of writing, European MEPs are due to vote on an EU-wide arms embargo to Saudi Arabia. Vested interests remain powerful, but the fact that major arms-supplying nations, like Britain, are breaking national and international law by supplying munitions for use against civilians in Yemen, might help focus the mind.

There is always a strong moral argument against selling arms. But in the case of Saudi Arabia, there are strong strategic and security reasons too.

The kingdom’s armed-to-the-teeth aggression is destabilizing the region. The proxy wars it is fighting with Iran in Syria and Yemen are wreaking havoc, writes conflict-expert Alastair Crooke on page 28. Saudi is arming and supporting the most extreme groups in Syria (Jaysh al-Islam, for example). It is using sectarianism as a political tool, to stoke up extremist sentiment in the region. This plays right into the hands of groups like IS. Al-Qaeda too has been given a new lease of life in Yemen, thanks to the Saudi intervention.

Whatever David Cameron says, selling arms to Saudi Arabia does not keep anybody safe. It increases the risk of terror attacks and worsens the refugee crisis. Ultimately, it’s self-defeating.

Western supporters of the Saudi regime often say that they can more effectively raise concerns about human rights if they have a friendly relationship with the perpetrator. If that is what they’ve been doing, they’ve been rubbish at it.

If Western leaders really do want to be friends with Saudi Arabia then why not extend a hand of friendship to the people of the country? How about reaching out to those imprisoned modernizers, described in Madawi Al-Rasheed’s article, who are asking for so little: just the basic freedoms most of us take for granted.

The hand could be stretched to the thoughtful young blogger Raif Badawi, 50 lashes into a life-threatening 1,000-lash sentence for expressing his considered and moderate opinions, now collected into a moving book entitled 1,000 lashes: because I say what I think.

Maybe that’s the sort of Saudi friend to have and defend.

![U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry chats with Deputy Crown Prince and Defense Minister Mohammad bin Salman after he arrived at Andrews Air Force Base in Camp Springs, Maryland, on September 3, 2015, to accompany King Salman bin Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia to visit President Barack Obama. [State Department photo/ Public Domain]](https://www.greanvillepost.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Secretary_Kerry_Chats_With_Saudi_Deputy_Crown_Prince_Mohammad_After_He_Arrived_At_Andrews_Air_Force_Base_Before_Meeting_With_President_Obama.jpg)