Why America May Be the Last Empire

TomDispatch [1] / By Tom Engelhardt [2]

TomDispatch [1] / By Tom Engelhardt [2]

To stay on top of important articles like these, sign up to receive the latest updates from TomDispatch.com here [3].

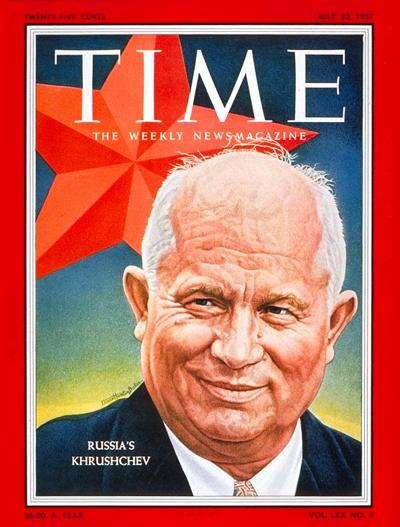

It stretched from the Caspian to the Baltic Sea, from the middle of Europe to the Kurile Islands in the Pacific, from Siberia to Central Asia. Its nuclear arsenal held 45,000 warheads [4], and its military had five million [5] troops under arms. There had been nothing like it in Eurasia since the Mongols conquered China, took parts of Central Asia and the Iranian plateau, and rode into the Middle East, looting Baghdad. Yet when the Soviet Union collapsed in December 1991, by far the poorer, weaker imperial power disappeared.

And then there was one. There had never been such a moment: a single nation astride the globe without a competitor in sight. There wasn’t even a name for such a state (or state of mind). “Superpower” had already been used when there were two of them. “Hyperpower” was tried briefly but didn’t stick. “Sole superpower” stood in for a while but didn’t satisfy. “Great Power,” once the zenith of appellations, was by then a lesser phrase, left over from the centuries when various European nations and Japan were expanding their empires. Some started speaking about a “unipolar” world in which all roads led… well, to Washington.

To this day, we’ve never quite taken in that moment when Soviet imperial rot unexpectedly — above all [6], to Washington — became imperial crash-and-burn. Left standing, the Cold War’s victor seemed, then, like an empire of everything under the sun. It was as if humanity had always been traveling toward this spot. It seemed like the end of the line.

The Last Empire?

After the rise and fall of the Assyrians and the Romans, the Persians, the Chinese, the Mongols, the Spanish, the Portuguese, the Dutch, the French, the English, the Germans, and the Japanese, some process seemed over. The United States was dominant in a previously unimaginable way — except in Hollywood films where villains cackled about their evil plans to dominate the world.

As a start, the U.S. was an empire of global capital. With the fall of Soviet-style communism (and the transformation of a communist regime in China into a crew of authoritarian “capitalist roaders”), there was no other model for how to do anything, economically speaking. There was Washington’s way — and that of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank (both controlled by Washington) — or there was the highway, and the Soviet Union had already made it all too clear where that led: to obsolescence and ruin.

In addition, the U.S. had unprecedented military power. By the time the Soviet Union began to totter, America’s leaders had for nearly a decade been consciously using “the arms race” to spend its opponent into an early grave. And here was the curious thing after centuries of arms races: when there was no one left to race, the U.S. continued an arms race of one.

In the years that followed, it would outpace [7] all other countries or combinations of countries in military spending by staggering amounts. It housed the world’s most powerful weapons makers [8], was technologically light years ahead of any other state, and was continuing to develop future weaponry [9] for 2020, 2040, 2060, even as it established a near monopoly [10] on the global arms trade (and so, control over who would be well-armed and who wouldn’t).

It had an empire of bases [11] abroad, more than 1,000 [12] of them spanning the globe, also an unprecedented phenomenon. And it was culturally dominant, again in a way that made comparisons with other moments ludicrous. Like American weapons makers producing things that went boom in the night for an international audience, Hollywood’s action and fantasy films took the world by storm. From those movies to the golden arches, the swoosh, and the personal computer, there was no other culture that could come close to claiming such a global cachet.

The key non-U.S. economic powerhouses of the moment — Europe and Japan — maintained militaries dependent on Washington, had U.S. bases littering their territories, and continued to nestle under Washington’s “nuclear umbrella.” No wonder that, in the U.S., the post-Soviet moment was soon proclaimed “the end of history [13],” and the victory of “liberal democracy” or “freedom” was celebrated as if there really were no tomorrow, except more of what today had to offer.

No wonder that, in the new century, neocons and supporting pundits [14] would begin to claim that the British and Roman empires had been second-raters by comparison. No wonder that key figures in and around the George W. Bush administration dreamed[15] of establishing a Pax Americana in the Greater Middle East and possibly over the globe itself (as well as a Pax Republicana at home). They imagined that they might actually prevent [16] another competitor or bloc of competitors from arising to challenge American power. Ever.

No wonder they had remarkably few hesitations about launching their incomparably powerful military on wars of choice in the Greater Middle East. What could possibly go wrong? What could stand in the way of the greatest power history had ever seen?

Assessing the Imperial Moment, Twenty-First-Century-Style

Almost a quarter of a century after the Soviet Union disappeared, what’s remarkable is how much — and how little — has changed.

On the how-much front: Washington’s dreams of military glory ran aground with remarkable speed in Afghanistan and Iraq. Then, in 2007, the transcendent empire of capital came close to imploding as well, as a unipolar financial disaster spread across the planet. It led people to begin to wonder whether the globe’s greatest power might not, in fact, be too big to fail, and we were suddenly — so everyone said — plunged into a “multipolar world.”

Meanwhile, the Greater Middle East descended into protest, rebellion, civil war, and chaos without a Pax Americana in sight, as a Washington-controlled Cold War system in the region shuddered without (yet) collapsing. The ability of Washington to impose its will on the planet looked ever more like the wildest of fantasies, while every sign, including the hemorrhaging [17] of national treasure into losing trillion-dollar wars [18], reflected not ascendancy but possible decline.

And yet, in the how-little category: the Europeans and Japanese remained nestled under that American “umbrella,” their territories still filled with U.S. bases. In the Euro Zone, governments continued to cut back [19] on their investments in both NATO and their own militaries. Russia remained a country with a sizeable nuclear arsenal and a reduced but still large military. Yet it showed no signs of “superpower” pretensions. Other regional powers challenged unipolarity [20] economically — Turkey and Brazil, to name two — but not militarily, and none showed an urge either singly or in blocs to compete in an imperial sense with the U.S.

Washington’s enemies in the world remained remarkably modest-sized [21] (though blown to enormous proportions in the American media echo-chamber). They included a couple of rickety regional powers (Iran and North Korea), a minority insurgency or two, and relatively small groups of Islamist “terrorists.” Otherwise, as one gauge of power on the planet, no more than a handful [22] of other countries had even a handful of military bases [12] outside their territory.

Under the circumstances, nothing could have been stranger than this: in its moment of total ascendancy, the Earth’s sole superpower with a military of staggering destructive potential and technological sophistication couldn’t win a war against minimally armed guerillas. Even more strikingly, despite having no serious opponents anywhere, it seemed not on the rise but on the decline, its infrastructure rotting out [23], its populace economically depressed, its wealth ever more unequally divided [24], its Congress seemingly beyond repair, while the great sucking sound that could be heard was money and power heading toward[25] the national security state. Sooner or later, all empires fall, but this moment was proving curious indeed.

And then, of course, there was China. On the planet that humanity has inhabited these last several thousand years, can there be any question that China would have been the obvious pick to challenge, sooner or later, the dominion of the reigning great power of the moment? Estimates are that it will surpass [26] the U.S. as the globe’s number one economy by perhaps 2030.

Right now, the Obama administration seems to be working on just that assumption. With its well-publicized “pivot” [27] (or “rebalancing”) to Asia, it has been moving to “contain” what it fears might be the next great power. However, while the Chinese are indeed expanding their military [28] and challenging [29] their neighbors in the waters of the Pacific, there is no sign that the country’s leadership is ready to embark on anything like a global challenge to the U.S., nor that it could do so in any conceivable future. Its domestic problems, from pollution [30] to unrest [31], remain staggering enough that it’s hard to imagine a China not absorbed with domestic issues through 2030 and beyond.

And Then There Was One (Planet)

Militarily, culturally, and even to some extent economically, the U.S. remains surprisingly alone on planet Earth in imperial terms, even if little has worked out as planned in Washington. The story of the years since the Soviet Union fell may prove to be a tale of how American domination and decline went hand-in-hand, with the decline part of the equation being strikingly self-generated.

And yet here’s a genuine, even confounding, possibility: that moment of “unipolarity” in the 1990s may really have been the end point of history as human beings had known it for millennia — the history, that is, of the rise and fall of empires. Could the United States actually be the last empire? Is it possible that there will be no successor because something has profoundly changed in the realm of empire building? One thing is increasingly clear: whatever the state of imperial America, something significantly more crucial to the fate of humanity (and of empires) is in decline. I’m talking, of course, about the planet itself.

The present capitalist model (the only one available) for a rising power, whether China, India, or Brazil, is also a model for planetary decline, possibly of a precipitous nature. The very definition of success — more middle-class consumers, more car owners, more shoppers, which means more energy used, more fossil fuels burned, more greenhouse gases entering the atmosphere — is also, as it never would have been before, the definition of failure. The greater the “success,” the more intense the droughts [32], the stronger the storms, the more extreme [33] theweather [34], the higher the rise in sea levels [35], the hotter [36] the temperatures, the greater the chaos [37] in low-lying or tropical lands, the more profound the failure. The question is: Will this put an end to the previous patterns of history, including the until-now-predictable rise of the next great power, the next empire? On a devolving planet, is it even possible to imagine the next stage in imperial gigantism?

Every factor that would normally lead toward “greatness” now also leads toward global decline. This process — which couldn’t be more unfair to countries having their industrial and consumer revolutions late — gives a new meaning to the phrase “disaster capitalism [38].”

Take the Chinese, whose leaders, on leaving the Maoist model behind, did the most natural thing in the world at the time: they patterned their future economy on the United States — on, that is, success as it was then defined. Despite both traditional and revolutionary communal traditions, for instance, they decided that to be a power in the world, you needed to make the car (which meant the individual driver) a pillar of any future state-capitalist China. If it worked for the U.S., it would work for them, and in the short run, it worked like a dream, a capitalist miracle — and China rose.

It was, however, also a formula for massive pollution [39], environmental degradation, and the pouring of ever more fossil fuels into the atmosphere in record amounts [40]. And it’s not just China. It doesn’t matter whether you’re talking about that country’s ravenous energy use, including its possible future “carbon bombs [41],” or the potential for American decline to be halted by new extreme methods of producing energy (fracking [42], tar-sands extraction [43], deep-water drilling). Such methods, however much they hurt local environments, might indeed turn [44] the U.S. into a “new Saudi Arabia [45].” Yet that, in turn, would only contribute further to the degradation of the planet, to decline on an ever-larger scale.

What if, in the twenty-first century, going up means declining? What if the unipolar moment turns out to be a planetary moment in which previously distinct imperial events — the rise and fall of empires — fuse into a single disastrous system?

What if the story of our times is this: And then there was one planet, and it was going down.

Tom Engelhardt, co-founder of the American Empire Project [46] and author of The United States of Fear [47] as well as a history of the Cold War, The End of Victory Culture [48], runs the Nation Institute’s TomDispatch.com [1]. His latest book, co-authored with Nick Turse, is Terminator Planet: The First History of Drone Warfare, 2001-2050 [49].

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook [50] or Tumblr [51]. Check out the newest Dispatch book, Nick Turse’s The Changing Face of Empire: Special Ops, Drones, Proxy Fighters, Secret Bases, and Cyberwarfare. [52]

Copyright 2013 Tom Engelhardt

Links:

[1] http://www.tomdispatch.com/

[2] http://www.alternet.org/authors/tom-engelhardt

[3] http://tomdispatch.us2.list-manage.com/subscribe?u=6cb39ff0b1f670c349f828c73&id=1e41682ade

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_states_with_nuclear_weapons

[5] http://books.google.com/books?id=Zv_IV4jucKAC&pg=PA4&dq=odom+soviet,+1998,+5.3+million&hl=en&sa=X&ei=q_J-UcO_CIX54APop4HoBA&ved=0CC8Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=odom%20soviet%2C%201998%2C%205.3%20million&f=false

[6] http://www.nytimes.com/1992/05/21/world/director-admits-cia-fell-short-in-predicting-the-soviet-collapse.html

[7] http://www.tomdispatch.com/blog/175431/chris_hellman_pentagon’s_spending_spree

[8] http://www.amazon.com/dp/1568584202/ref=nosim/?tag=tomdispatch-20

[9] http://www.tomdispatch.com/post/2298/nick_turse_if_you_build_it_they_will_kill

[10] http://www.tomdispatch.com/post/175207/tomgram%3A_frida_berrigan,_pimping_weapons_to_the_world/

[11] http://www.tomdispatch.com/post/1181/

[12] http://www.tomdispatch.com/blog/175338/nick_turse_planet_of_bases

[13] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_End_of_History_and_the_Last_Man

[14] http://edition.cnn.com/ALLPOLITICS/time/2001/03/05/doctrine.html

[15] http://www.tomdispatch.com/blog/175336/engelhardt_the_urge_to_surge

[16] http://www.informationclearinghouse.info/article2320.htm

[17] http://news.brown.edu/pressreleases/2013/03/warcosts

[18] http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=87855957

[19] http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/23/world/europe/europes-shrinking-military-spending-under-scrutiny.html

[20] http://permalink.gmane.org/gmane.politics.marxism.marxmail/168320

[21] http://www.tomdispatch.com/blog/175687/tomgram%3A_engelhardt%2C_the_cathedral_of_the_enemy/

[22] http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/unitedarabemirates/10024002/Britain-may-reverse-East-of-Suez-policy-with-return-to-military-bases-in-Gulf.html

[23] http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-201_162-57575112/u.s-gets-d-on-infrastructure-report-card/

[24] http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/04/23/a-rise-in-wealth-for-the-wealthydeclines-for-the-lower-93/

[25] http://www.tomdispatch.com/blog/175545/hellman_kramer_war_pay

[26] http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/11/world/china-to-be-no-1-economy-before-2030-study-says.html

[27] http://www.tomdispatch.com/post/175476/tomgram%3A_michael_klare,_a_new_cold_war_in_asia/

[28] http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/02/world/asia/china-likely-to-challenge-us-supremacy-in-east-asia-report-says.html

[29] http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/strengthening-of-chinese-navy-sparks-worries-in-region-and-beyond-a-855622.html

[30] http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/22/world/asia/as-chinas-environmental-woes-worsen-infighting-emerges-as-biggest-obstacle.html

[31] http://www.tomdispatch.com/blog/175386/engelhardt_china_as_as_number_1

[32] http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=climate-change-threatens-second-dust-bowl

[33] http://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-01-12/climate-commission-predicts-more-heatwaves-bushfires/4461960

[34] http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/13/130215-severe-storm-climate-change-weather-science/

[35] http://www.serdp.org/Featured-Initiatives/Climate-Change-and-Impacts-of-Sea-Level-Rise

[36] http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/09/science/earth/2012-was-hottest-year-ever-in-us.html

[37] http://www.tomdispatch.com/blog/175690/michael_klare_the_coming_global_explosion

[38] http://www.amazon.com/dp/0312427999/ref=nosim/?tag=tomdispatch-20

[39] http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2012/dec/17/pollution-car-emissions-deaths-china-india

[40] http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2013/apr/29/global-carbon-dioxide-levels

[41] http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2013/jan/22/china-australia-carbon-bomb

[42] http://www.tomdispatch.com/post/175695/tomgram%3A_ellen_cantarow%2C_big_energy_means_big_pollution/

[43] http://www.tomdispatch.com/blog/175648/michael_klare_xlpipeline

[44] http://www.tomdispatch.com/blog/175523/michael_klare_welcome_to_the_new_third_world

[45] http://www.cnn.com/2013/01/14/opinion/ghitis-obama-energy

[46] http://www.americanempireproject.com/

[47] http://www.amazon.com/dp/1608461548/ref=nosim/?tag=tomdispatch-20

[48] http://www.amazon.com/dp/155849586X/ref=nosim/?tag=tomdispatch-20

[49] http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B0086EF89K/ref=as_li_ss_tl?ie=UTF8&tag=tomdispatch-20&linkCode=as2&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=B0086EF89K

[50] http://www.facebook.com/tomdispatch

[51] http://tomdispatch.tumblr.com/

[52] http://www.amazon.com/The-Changing-Face-Empire-Cyberwarfare/dp/1608463109/

[53] http://www.alternet.org/tags/empire

[54] http://www.alternet.org/tags/us-empire-0

[55] http://www.alternet.org/%2Bnew_src%2B