MAKE SURE YOU CIRCULATE THESE MATERIALS! BREAKING THE EMPIRE'S PROPAGANDA MACHINE DEPENDS ON YOU.

A Book Review

What You Have Heard Is True: A Memoir of Witness and Resistance by Carolyn Forché

“Friend, hope for the Guest while you are alive.”

– Kabir, “To Be a Slave of Intensity”

Strange how a man

Can enter your life

Just like that: a knock

Out of nowhere

And you’ve slipped away

To a rendezvous with destiny

That always awaited you.

— EJC, “The Birth and Death of Trauma”

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]yths and popular tales, like life, are replete with accounts of those not answering the call, of locking the door to their hearts and shutting themselves up in sterile and safe lives where the rest of the world is not even an afterthought, where others suffer and die because of one’s indifference. Answering can be very dangerous, for it can take you on a journey from which you may never return, surely, at least, as the same person. Only the courageous heed the call.

When Carolyn Forché, a twenty-seven year old naïve academic poet living in the San Diego area, miraculously answered the call of a Salvadorian stranger named Leonel Gómez Vides, who showed up at her door out of the blue, to go to El Salvador, a country she knew very little about but to which he said war was coming and her poet’s eye was needed, she acted intuitively and bravely from her deep soul’s murmurings and said yes, not knowing why or where she was heading except into the unknown.

This memoir, a souvenir of hope and terror and a call to resistance, a poet’s lucid dreaming between childhood and an adult awakening, invites the reader to examine one’s life and conscience through language that emulates our living experience as it strains toward meaning through a wandering dialectical consciousness that weaves the past present with the present past and lucid dreaming with the waking state. One experiences this book as one does life, not, as the French existentialist Gabriel Marcel, has said, “as a problem to be solved but a mystery to be lived.” It is impossible to adequately “review” a book that breathes. One can only conspire with it to uncover the conspiracy of silence that is American government propaganda.

For at the heart of this mystery are facts, which Forché describes in graphic detail, the truth of how the United States government has long been doing the devil’s murderous work in El Salvador, throughout Latin America and the world, as current events confirm. Forché asks us to enter into her memories not to wax nostalgic, but to wake to the truth of today. The truth that little has changed and the past was prologue. The U.S. is still “Murder Incorporated,” and Americans must see this clearly, and resist.

Carolyn’s “Yes” to the enigmatic stranger Leonel, so I sense from her reveries, was the fruit of a seed of faith planted when she was a child of ten or so in Michigan. “The girl I once was, who had been a Catholic, woke for the bells of the Angelus at six in the morning, Angelus Domini. I sang to myself as I walked to morning Mass under a canopy of maples, through a wetland of swamp cabbage and red-winged blackbirds, the quiet, low Mass where it was possible to pray in peace, with the Latin liturgy a murmur in the air….I felt at peace in the church, on the padded kneeler near the stained-glass windows depicting the seven sorrows along the west wall, the seven joys along the east….When I knelt beside them, the floor, the pews, and my own body were quilted in colored light.” But she tells Leonel that she has “fallen” because she no longer attends Mass.

Leonel, a “non-believer” who says “I believe with my life, how I live,” tells her about Padre Rutilio Grande, a Jesuit priest who was murdered with an old man and a boy by the U.S. trained and supported Salvadorian death-squads. “God that Padre Grande taught was not up in the sky lying in some damn cloud hammock. This was a God who expected us to be brothers and sisters and to make of earth a just place.”

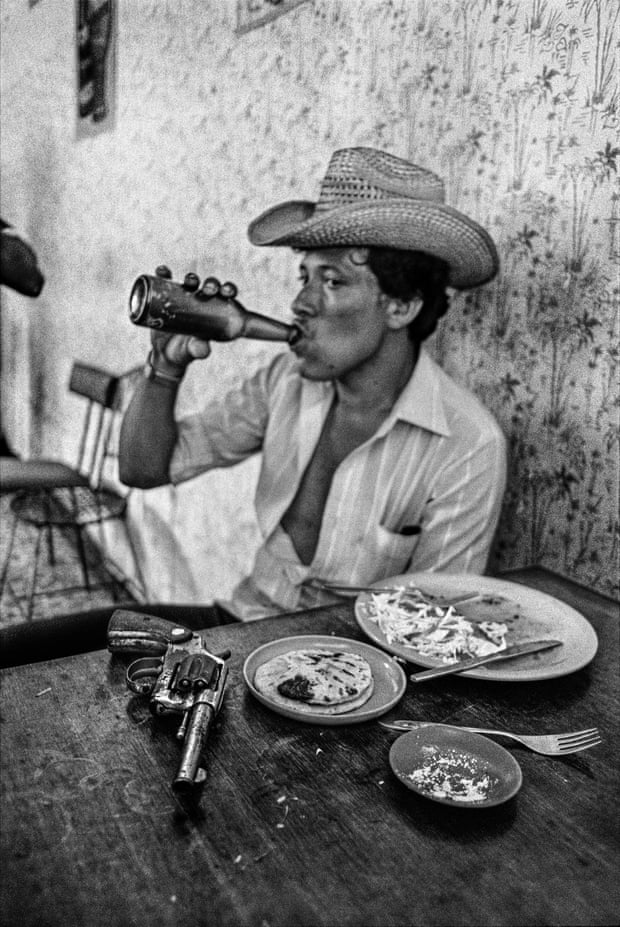

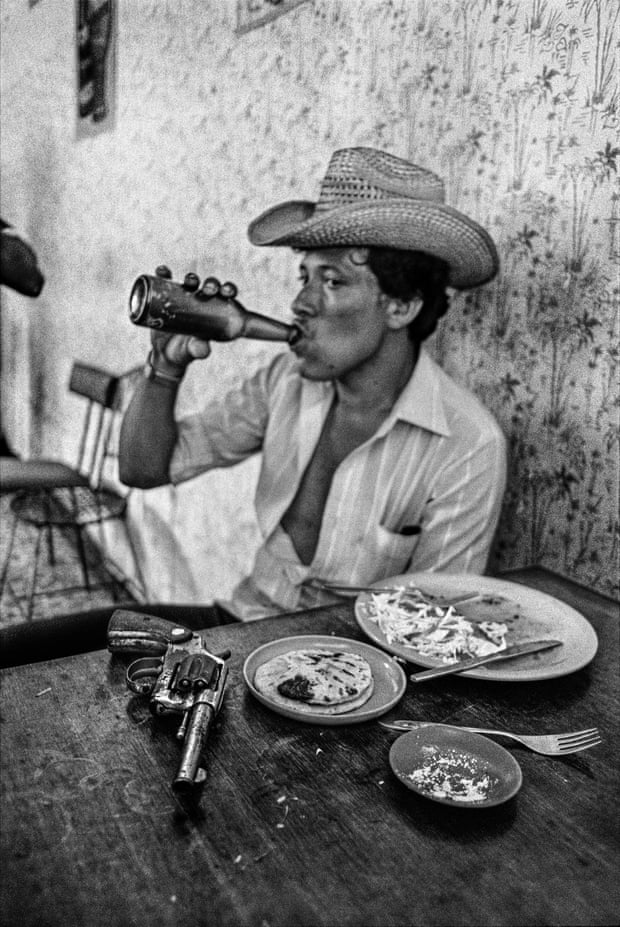

Derek Hudson's legendary picture of a Salvadoran death squad member. The photo almost cost the photographer his own life.

This was her introduction to a new theology, a way of connecting her spiritual core from a conservative Catholic childhood piety to the liberation theology that created Christian base communities of the poor and persecuted in El Salvador and other Latin American countries. Dissident Christianity. True Christianity. When she went to El Salvador soon thereafter, not only did the poet leave the quiet of her study where her work might have revolved around herself, but the little girl left the church building to discover, as a changed woman, Christ among the poor and persecuted in the living world.

One night she meets a man in the shadows of such a Christian base community where a few of its members had been killed and dismembered by the government death squads. His pseudonym is Inocencio. “You can say Chencho,” he tells her. At first he thinks she is a nun, (“although,“ as a girl, “I considered that vocation.”) because she smokes, and some of the foreign nuns smoke and don’t dress in traditional habits. He asks her why she is there and she says, “You know, I’m not sure.” She then explains how an unnamed person invited her to come to see the truth for herself because war was coming, and when she returned to the United States to “explain the reasons for the war to the North Americans, because my friend tells me that this will be important, that the real reasons be known, so that the people of the United States understand.”

Chencho is a catechist who secretly moves under darkness of night from one small Christian base community to another, encouraging the campesinos to keep the faith because God is with them, la gente, los pobres, the people, the poor. He says to Carolyn,

Listen to me, hermana. We are brothers and sisters in Christ, and Christ is moving through the world now, through us. He is acting through us in the struggle against injustice, poverty, and oppression. To be with God now is to choose the fate of the poor, to be with them, to see through their eyes and feel through their hearts, and if this means torture and death, we accept. We are already in the grave.

Later, Leonel takes her to visit a friend who is in a prison from hell where men are tortured in padlocked wooden boxes the size of washing machines. Afterwards she vomits. Then they go to visit a dirt poor young mother give birth in a casita in which there was nothing, “really nothing: a candle, a plastic basin, a ladle hanging against the wall, and, in the candlelight, the shadow of a wooden chair dancing on the wall.”

I followed him [Leonel] through the darkness into a passage, then through a door lit by a candle and, by the light of it, saw people gathered and one of them, someone, took me by the hand and drew me into the circle surrounding a young woman who was lying on her side on a blanket on the floor, her head propped in her hand. There was a cardboard box beside her, and in the box, a newborn girl with her hair still wet, lying in a towel. Leonel was looking at me from across the room. ‘She was born about a half hour ago,’ a young man beside me whispered. ‘She’s early. We’re going to name her Alma. Bellisima!’

Then it is on through night to meet with four young impoverished men who read their “political” poems for her, written under pseudonyms for fear for their lives, poems they hope might stir the hearts of people in the United States.

That night I knew something had changed for me, and that I wasn’t going to get tired or need a shower or want to call something off so I could rest, and I hoped that if I forgot this I would somehow remember Alma in the cardboard box in the barrio, and the mimeographed poems….The woman who went into the prison in Ahuachapán left herself behind in a barrio called La Fosa, the grave.

The naïve young poet is buried and the political poet of witness is born. It is impossible not to be deeply moved and nourished by such a birth. Who, I wonder, are the “fallen” ones? What is writing for? What good are poets? Why say yes to a stranger’s request when it is so much easier to not answer the knock on the door? So much easier to barricade ourselves behind walls of denial and say “me first.” So much easier to ignore the truth that this book reveals: that the United States is the greatest purveyor of violence in the world and our society rests on keeping the poor poor and under the vicious thumbs of the rich.

The world is filled with writers who witness only to their imprisonment in their own egos. When Carolyn Forché said yes to Leonel and then returned from El Salvador to write “political” poems such as “The Colonel,” she was attacked by writers wishing a poet would stay in her box and not disturb their universe. That she was not like them angered them, J. Alfred Prufrocks who were not going to come back from the dead to tell us all as she has, poets who had time on their hands to neurotically contemplate their navels with their fellow Americans:

Time for you and time for me,

And time yet for a hundred indecisions,

And for a hundred visions and revisions,

Before the taking of a toast and tea.

Having heard Leonel’s descriptions of “the silence of misery endured” and the American supported death-squads massacring impoverished Salvadorians, she tells us,

I knew that if I didn’t accept his invitation, I could never live as if I would have been willing to do something, should an opportunity have presented itself. I could never say to myself: If only I’d had the chance. This was, I knew, my chance.

Wasn’t such a daring decision by this “fallen” poet the quintessence of the creative act, exactly what inspired artists do when they see the act of writing as an adventure into the unknown where startling truths wait to reveal themselves to the unsuspecting author? A journey fraught with danger and delight, perhaps delightful danger or dangerous delight, but always ready to surprise with hidden truths that might unlock the prison gates that enclose the world in suffering and pain? Does not the artist proceed into this alien territory armed only with a fierce faith in the power of truth to reveal its face and so strengthen us through disarmament? Doesn’t a poet trust in a power greater than herself and know what she wishes to say only in the act of saying it? Isn’t real writing a transmission between the creative spirit and the world of flesh and blood, the living and the dead, a visionary opening into the future where freedom beckons?

Carolyn somehow knew this then and now, and her memoir is the result, a haunting trip into the past to liberate the present. “The strange, mysterious, perhaps dangerous, perhaps redeeming comfort that there is in writing,” wrote Kafka in his diary. Perhaps there are certain writings that cannot be adequately reviewed but must be experienced. As I said, I think What You Have Heard Is True: A Memoir of Witness and Resistance is such a book. How do you review a prayer and a mystery? You must enter them if you are willing.

Carolyn, drawing on the uncanny spirit of her mystical, Gypsy-spirited Czechoslavian grandmother Anna (“I will get Anna out of you if it’s the last thing I do” her mother told her, to no avail), chose to develop her “legitimate strangeness,” as the French poet René Char urged, heeding his words that “what comes into the world to disturb nothing merits neither attention or patience.” Disturbed and perplexed by the stranger’s tales and her former husband’s experiences in Vietnam and the United Sates’ savage war there, as well as by her mystical Catholic childhood’s faith and its tug of conscience, she joins the mysterious Leonel in El Salvador.

Carolyn Forché (left) and Claribel Alegría in Mallorca in 1977.

To those ensconced in instrumental rationality, her decision seems insane. However, instrumental rationality is insane, and it has taken us to the brink of nuclear extinction. It is to the poet’s truth we should turn. The data driven instrumental rationalists have given us WW I, II, Auschwitz, Vietnam, the CIA, death squads, Iraq, Syria, etc. – should I give you numbers, list it all, do the logic? When has such logic convinced the disbelievers? Logicians don’t trust the soul’s promptings and, like Carolyn, take a chance, take a leap of faith. They do calculations, follow computer models, and dare not enter the world outside if they are told there is a 60% chance of rain. And if they are told the sun will shine and all will be well with the world, but a hard rain does fall and the poet shouts there is blood on our hands, they act shocked. Always shocked at the truth that was there from the start. If only we had known.

Is it any wonder so many Americans are depressed?

For Carolyn, the child of Czechoslovakian ancestry, the German holocaust atrocities haunted her, and she grew up suffering from periodic depressions that would lift once she felt the urge to do something about the injustices she saw. The urge to act for others freed her from wallowing in depression. Rather than becoming a nun, she became a poet, and when Leonel told her that an American poet was needed to witness the truth of the American supported atrocities in El Salvador, she trusted the spirit to lead her on, not knowing why this might be so. What use are poets, she wondered, in the U.S. poetry “doesn’t matter.” She would soon help change that.

There is an old Catholic prayer that goes like this: “Come Holy Spirit, fill the hearts of your faithful and kindle in them the fire of your love. Send forth your Spirit and they shall be created. And You shall renew the face of the earth.”

Might such words have bubbled up from her unconscious? I have long felt it was a prayer for poets as well as the religiously faithful – are not all inspired together? Is there a difference? “I believe in the magic and authority of words,” said Char, the French resistance fighter. Witness and resistance. Words. Poetry. Prayers.

It is best that I not tell you too much about Leonel. You will wonder about him, and you will wonder with Carolyn what her relationship with him is all about. You will discover his essence in the reading. You will learn that he once said to Carolyn that “it isn’t the risk of death and fear of danger that prevent people from rising up, it is numbness, acquiescence, and the defeat of the mind. Resistance to oppression begins when people realize deeply within themselves that something better is possible.” You might, like me, question whether this is true only for the most oppressed, or whether it applies to Americans whose lives depend on the subjugation of others in foreign lands.

You will be terrified to learn of the death squads, the brutality and cold-bloodedness of their murders, and Forché’s close escapes as they hunted her. You will feel her fear.

You will learn of the courageous women who befriend her, her meeting with Monseñor Oscar Romero the week before he is assassinated while saying Mass and Carolyn has left the country at his urging, and you too will be lost in reveries as you travel between worlds of night and day, wealth and poverty, life and death, now and then.

If you are like me, you will be inspired by what the poet Char called “wisdom with tear-filled eyes.” This book is just that. It is a call to Americans to face the truth and resist.