17 “Between Scylla And Charybdis”

(Reggio, August, 2001)

Circling over the Straits of Messina Airport in Reggio-Calabria, I feel my vision encompasses the entire world of antiquity. Any atlas in fact confirms the geographical unity of the world on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea. Entering the Mediterranean world from the West through the narrow Straits of Gibraltar is to step back in time. Though I’ve come to love especially the arch of the northern coastline reaching from Gibraltar to Naples—the Latin Mediterranean—I feel the whole sea is my sea, lined by an extraordinary diversity of ancient peoples and cultures, from Spain and Morocco to Tunisia and Italy, to Greece, Syria, Lebanon and Palestine, interlinked by a common heritage and erratic histories. The Great Sea today remains one of the important maritime routes in the world, comprising three continents and three monotheistic religions.

…

Though disputed among its peoples, its climate and magic have attracted to its shores countless non-Mediterranean peoples—both conquerors and colonizers in search of a new way of life. For my receptive eyes indeed a soothing vision, albeit, I recognize, also an historical optical illusion. Though against the backdrop of puritanical skies the ancient world appears in memory as a world far superior to what I see under the sinking plane’s wobbling wings, I fear my conclusion is wishful thinking, and that old times were not at all good times. Yet since the scope of my vision makes me tiny in the immensity, I want to bow in reverence to the ubiquitous dark blue-green seas omnipresent in the minds of each member of the human landscape taking form below … reminding me of our song’s words, my blue-green colors flashing.

Not only the Bel Paese—as Italians call this beautiful peninsula jutting out into the sea toward nearby Tunisia—attracted me to these ancient lands. I hoped to grasp the whole Great Sea around which Western civilization developed; I set for myself the goal of knowing all the lands surrounding it. I felt the same allure felt by the succession of peoples and civilizations that have fought to control these lands. Many seemed to succeed but in reality they themselves were absorbed by the lands they conquered, so that the question remains: Who conquered whom? History shows that the Mediterranean world absorbs new peoples and cultures more quickly than does Teutonic north Europe. In my experience I have found that persons who grow up in Rome consider it their home for the rest of their lives.

From above, Reggio appears only a stone’s throw distance from Messina across the three-kilometer wide straits separating the Continent from Sicily. As the plane banks, my view reaches from the Aspromonte mountains—just that name provokes in me a certain panic—to the toe of the peninsula now fading away at my back. My eyes wander from the lonely Eolian islands north of the Sicilian mainland to Mount Etna in southern Sicily, slashes of red lava dribbling down its flanks. I am at the geographical center of the Mare Nostrum of the Romans, descending toward a city I try to imagine as it once was: the Greek Rhèghion, one of the biggest cities of Greek colonists. Founded in the eighth century b.c. the Greek city is one of Europe’s oldest cities. Mind-boggling that Reggio-Rhèghion was already old at the beginning of the second millennium, mysterious, dark and somber, alive and unchanging, unlike today’s Reggio, dangerous and lacking in hope. Reggio is a letdown in comparison to Rhèghion and its port welcoming biremes and triremes and long-range Pentercosters carrying merchandise and immigrants sailing from Greece across the Ionian Sea to Magna Graecia and the great city where Greek colonists disembarked in the America of their era. Today’s Reggio is indelibly marked by nostalgia for its lost magnificence and by the sadness lingering in its collective memory, a city that harbors dark secrets, on the one hand a part of modern Italy, but on the other constituting a parallel world hidden away even from most of its bewildered inhabitants who continue imagining they are living normal lives in the most abnormal of worlds. Though still spilling along the sea, contemporary Reggio is the center of a metropolitan area of one million people governed by organized crime, corrupt administrators and burgeoning fascism … its festering rottenness visible to the naked eye.

[dropcap]I [/dropcap]rent a car at the airport and drive downtown. My contact in Reggio is the owner-manager of a local alternative TV news station. Gino Rocca is an investigative reporter and critic of the operations of both the organized crime of the ‘ndrangheta and a budding neo-fascist movement, which together control the region’s police and Carabinieri forces.

Contrary to expectations there is little traffic on the roads of the periphery; even less in town. Open-bed trucks of sand and rocks, here and there dusty old buses, older model cars, a disproportionate number of big new cars, chiefly black SUVs, and polished black or blue Mercedes and Audis, the autos preferred by Mafiosi.

In a narrow side street I find his tiny studio—airless, crowded with cameras, microphones, laptops, and dusty stacks of newspapers including mine. His two female assistants chat me up and offer coffee.

Gino Rocca is tall and skinny, with a curled mustache and long dirty blond hair. He speaks in the agitated way of a person for whom everything is of maximum importance and which he tries to say all at once while his hands constantly fidget with something. His friend at my newspaper told me he was both a genius and totally uncunning.

“You ask where our police stand today,” he begins at once. “The standing order is shoot first and ask questions later. Fascists shoot Mafiosi busily shooting each other for control … both shoot nosey outsiders.”

“Who gives such orders?”

“Orders are unnecessary. That’s the way our society is. You know, at times I think that the potential lack of blood and death makes us despair. As if we weren’t really alive without shooting and destruction … and the smell of blood.”

“Yet you survive.”

“Oh yes, we survive … as we have for thousands of years. Yes, we survive. The Premier himself—like all the premiers before him—promised order and security in the Mezzogiorno. Now, the Fascists in the city and a secret army in the mountains are vying for the right to execute his orders … and to kill him too. Create order! And killing enemies to do it. Killing refugees and killing Italy. Tonight I’ll take you out. There’s no moon. No hard winds, the sea calm. Though clandestine immigrants land here in lesser numbers than in Sicily, the beaches will be swarming with speedboats and police tonight. You’ll see. Our gallant forces will line the coastline to protect the homeland from the invader.”

“And the secret army?” Again that word sends chill bumps down my spine. Well, as I said, each man to his own fears. Oh, fuck!

“You’ll see them too,” Gino adds enigmatically.

At midnight we drive to a village along the coast east of the city. He parks off the road, facing an open beach. A man sits in silence in the back seat, an Arabic-speaking interpreter. The radio is tuned to Gino’s private frequency. A clear but moonless night, the coastline is lit up like a circus—spotlights from hovering helicopters sweeping back and forth over the area and headlights of stationary jeeps and trucks pointed toward the sea. Armed police troops in pairs patrol the beaches. Sparks from beach fires here and there dance in the breeze blowing in from the seas. Launches speed across the waters a few hundred meters from the shore in the direction of Messina across the strait. Not even a mafia launch could penetrate the cordon sanitaire. Certainly no refugee could swim onto that point on the coast. A TV cameraman nearby is filming the whole scene which Gino says is staged for the TV reporters. Gino doesn’t touch his camera.

Near us, five persons are sitting immobile and mute in an unmarked Suv, their blackened faces nearly invisible in the night. The vehicle is black, the license plate illegible. When I photograph it some of the black faces turn toward my flash.

“Who are those guys?” I ask in a loud voice, hoping they hear me.

“The secret army,” Gino answers softly. “I’ve seen them on the beaches the last two weeks. A private para-military police. I’ll show you where they train another time.”

“What’s going on here? Who do they think they are? Gladio?”

Gino looks at me and grins. He is fiddling with the radio, uninterested in the scene we are witnessing. His radio sputters. He turns up the volume. A woman’s voice crackles: “Gino, you were right. They’re farther east, near Stracia. A few of those soldiers too. Hurry!”

“The show here is for foreigners, visiting journalists and the Premier’s TV. To reassure Europe that we’re cutting the flow of the refugee hordes arriving from the lands to the south and east. To show the alertness of our security forces against the nocturnal invasions of dangerous aspirant immigrants … most of whom, they say, are criminals, maybe armed, and infested by terrorists in their ranks. I wanted you to see it. The real action is elsewhere.”

He does the some twenty kilometers to Stracia on a narrow winding road in eighteen minutes, talking all the time. “The Mediterranean is a graveyard. A slaughterhouse of dark-skinned people. Divers say you see on the sea bottom here everything from the remains of hands and feet, legs and heads to ancient Greek statues, vases and pots mixed among car parts, gas stoves, even couches and stuffed chairs. Everything. From the moment they leave North Africa or Albania, our military radar monitors every boat of the traffickers in human beings. If the traffickers don’t throw the refugees overboard first, someone blasts away at them. Half of them never make it to land. Recovered bodies just get a number and the name ‘Unknown’. There’s a police section down here that deals in body parts that are filed away according to type.”

We stop on a sandy stretch of seashore. Two army jeeps are parked near the lapping smelly water. Farther back from the waterline, apart from the rest, two black Suvs. The bay itself seems innocent in the clear night but Gino says it’s “as polluted as a sewage dump”. At the waterline soldiers stand in a circle near a group of some thirty people. Many children. All poorly dressed and wringing wet. Many crying as if aware of the danger of this haven in the night. Like the soldiers, they seem to be waiting for something to happen or for someone to save them. Some of the soldiers are gentle and tactful, as if the tears of the others called forth unexpected instincts of tenderness in the warlike nature of white men when freed from the constraints of civility.

Gino speaks to the soldiers and points at me. One of them nods.

I spot a woman dressed in black with three small children pressed close to her. The children are crying. Gino unfolds a blanket and offers it to the woman who wraps it around the two smallest children. The tiny interpreter asks her to tell us about her trip. She nods and leads the children a few steps away from the others.

“Why is everyone crying?” I ask, and turn on my tape recorder. Gino aims his camera at us.

“The boat traveling with our friends … they sank it,” she tells the interpreter.

“Where? Why”

“Far out in the water. They’re all dead. They want to kill us all.”

“Sank?” I ask. “How?”

“They shot it,” the interpreter translated her words into Italian. “A big explosion. Everybody fell into the water. It was dark.”

“So how did you and the children get here?”

“Men in uniforms brought us on a ship. They think we will all die.”

“Why is that?” I ask, looking around the beach area. Some soldiers give them food and water. No wonder the armed men don’t relish their work: the atmosphere is macabre … the search lights and the noise of running motors creating a calamitous reverberation as in the silence following the explosion of a bomb. Italians are not yet real racists like you see in America even though they regard these foreigners as aliens from another planet.

The woman looks at the interpreter as if afraid to answer. “Because they don’t know what to do with us.”

I look at Gino. He is filming everything. “This is going out live,” he whispers. We both know the woman and children will be sent back to where they came from.

She is from Chad. Her husband had left two years earlier. He is in Germany and sent her money. She paid five thousand marks for transportation from Chad to Libya to Germany. In Chad they had nothing. No possessions, no house, no schools, no medicines, no life. Her little girl has had a bad cough for over a year. They lived in a hut and existed on food from relatives.

Two weeks later I take the Rome-Reggio night train to meet Gino again … this time to visit the mysterious Aspromonte Mountains, the domain of criminals on the run and killers for hire. I have no idea what the upshot of the affair is to be but I sense that a major event is developing on the mountainous tip of the peninsula. It’s a hunch based on what I know of Gino and his TV station and the flow of refugees through the gateway from hell to opulent Europe. But above all because of something alarming concealed in those sinister mountains.

The trip down the darkened peninsula fulfills my expectations. Nothing exceptional happened until a sudden halt at a small station in the dark countryside south of Salerno. The train squeaks to a halt. The engine falls silent. Interior lights blink off, then return on dim. Passengers descend from my car and look around at the surroundings. A surprising number of people are waiting in groups or walking up and down a narrow platform, waiting for who knows what train headed for mysterious destinations. In the yellow-tinted darkness a kind of intimacy is born among the deboarded passengers.

In principle I love the night. Yet I’m wary of it too. The night is the time when unpredictable things happen. The night is the time when you might realize that one of the big moments of your life is about to happen and you know that afterwards nothing will ever be the same in your life again.

Gradually the people strung out along the platform in semi-darkness become aware of the reason for our nocturnal halt. After a steadily mounting dull beat from the distance, the roar and the reflections from the lights of the Palermo express flicker off whitewashed station walls in rhythm with the clicking over rail links of each passing car. Despite the only apparent speed and the pounding of steel wheels against iron rails, the silhouettes of marionette-like bobbing heads high up inside the illuminated cars flashing past above us seem to seek contact with our insignificant figures below, our faces, I imagine, whitened and motionless, lost in the night alongside the tracks of the small town station. The station master stops in mid-step, his torso twisted toward the thunder roaring past his station. A circle of tall, sun-tanned Boy Scout-looking types dressed in white shirts with red kerchiefs around their necks and bulging knapsacks strapped on their backs stand immobile at one end of the station building, their youthful heads lifted toward the sparkling white and yellow lights. In the glass-encased office facing the tracks, the slow motion activity near illuminated control boards is submerged by the beast running over and through the small room itself. I look toward the darkness of an outlying shed and note just behind it the same weak interior lights of a local train, stationary on a side track. From the station side the faint light from the traffic office, the dim lights of our waiting train silent as if in awe of the powerful Palermo express, and here and there a flashlight casts otherworldly attempts of light on the scene, visible only for the fraction of a second between each car speeding past. Time too flicks past, marked by the clickedy-clack, clickedy-clack from the express track. My head nods in harmony and my eyes shift from left to right, left-right, left-right, until motion seems to become circular and the station itself spins on a vertical axis of shadows and the steel-on-iron rhythm.

In that moment of mental and physical disequilibrium I note again the tall man who has been striding up and down the platform now seemingly approaching me, his head however turned toward the tracks and his hand outstretched as if seeking balance. He is leaning slightly backwards and his feet move forward ahead of his body, each foot sweeping from side to side feeling for the edge of the platform. His face framed in long silky hair is chalky, the way all of us on the platform must appear to the express passengers observing us aliens in the night. For some reason I imagine him as Isabel’s husband whom I have seen only once, in a similar momentary shaft of light on a snowy Munich night on Giselastrasse. Was he too blind to what was happening? The echo of the roar has not yet faded away when the lights brighten inside our high elegant cars with Roma-Reggio Calabria inscribed on plaques near the doors and the sound of its engines returns and the conductor calls out into the night: “All aboard!”

I climb the steep steps.

When I step through the sliding doors into the now gaudily bright first-class compartment, the country station and the Palermo express and the ghostly figure on the platform of Isabel’s imaginary husband cease to exist. Maybe he never did. Yet I know that even the most insignificant of us leaves behind an emptiness that is something. Perhaps an omen.

A few seconds after I step out of Reggio’s main station, Gino Rocca’s familiar tan Ford Fiesta pulls up in front of me, the Fiesta’s passenger door crackles, and his lanky figure climbs out.

Having promised me something “surprising, stunning and sinister”, Gino asks right off: “What about a ride to the mountains? Or are you too tired.”

“That’s why I’m here. But aren’t you afraid to be seen with me? You’re in hot water yourself.”

He grins and shrugs, his nerves probably on edge as always.

“You don’t look so good,” I say.

“Just nerves. These are dangerous times in good old Rhéghion.”

“You don’t have to do this.”

“You didn’t see much on your last visit. A miracle you got away in one piece.”

“I thought about that too … but here I am again.”

“You shouldn’t be here. They love cracking the heads of curious journalists … from elsewhere. They’re used to me.”

“Stinking cowards, eh?”

“The kind who kill in the dark or who shoot down kids on the street.”

“But why all this violence, Gino?”

“They’re different from other people.”

We head north toward the Aspromonte. I note more of the black Suvs both downtown near the station and in the suburbs. Soon we’re passing through the periphery, through degraded suburbs that once must have been attractive villages facing the sea where affluent people of Reggio had beach houses. Gino speaks of peasant farmers forced to leave their homes by the creeping modernistic economic tentacles of old Rhéghion. He points out half-finished buildings that look as if they’d been that way for decades, flanked by vacant lots and more or less finished structures, flaking, crumbling and rotting away, maintenance being an attribute absent in the Mezzogiorno. A desiccated and dying past decorated vulgarly by huge political posters. A past dying from negligence and displacement of peoples and objects infected by despondent changelessness. People hanging on in the former villages, people acquiescent to suffering, according to some politicians in Rome deserving of it because they are poor and lazy, three generations of families living with their impotent hatreds and dulling ignorance in precarious two-story structures and surviving on occasional useless jobs in the city to which they travel early mornings on rickety buses. Otherwise, I imagine, they sit around in garlic-infested rooms drinking sweet homemade wine and talking with thin old men and elephantine women about the good old times, while dogs run in and out and the walls of a former life crumble around them. Places from whose kitchens families overflow into adjoining houses and everyone mingles with the misery of everyone else in the delirium of a world in which misery is the common denominator. Rich people used to live here. Now it looks like I imagine the edge of hell. The center of the sprawling abandon surrounding the city where rebellion should be brewing lies in silence.

“What about the big cars, Gino?” I ask pointing to a dark blue Audi parked in front of a rundown two-story house. “I’ve counted three new Mercedes in the last kilometers and that’s the second Audi.”

“Not only the ‘ndrangheta likes such cars but also new people arriving from Sicily. Representatives of American humanitarian organizations—NGOs of course—here to aid refugees, they say. I’ve investigated a bit. Found no evidence of actual help. There’s also a new group that calls themselves Blue Helmets. Sometimes they really wear one. Not often though. Another Non-government Organization! All foreigners.” He glances at me and shrugs: “Go figure.”

Gino points east and says: “That road doesn’t lead anywhere. It ends down there around a curve among abandoned factories at a half-finished bridge. After that you see only walled fields of wild weeds bordering the sea … the symbol of the Mezzogiorno of Italy.” Then, abruptly, a few fields and gardens to the east are brilliantly golden in the rising southern sun, as if showing their best to me the visiting journalist. Even though the sea is close, this narrow part of the peninsula seems unlimited. The occasional touch of the wild is inevitably marred by improvised, semi-clandestine dumps. As Gino slows to a near stop I try to identify the objects filling an unmarked danger zone filled with rusted and gutted car bodies, wheelless motorcycles, crooked pipes now turned green, unidentifiable sheets of bent and moss-crusted metal from who knows what abandoned factory, former stereo sets, parts of bedsteads and yellowish mattresses, No Parking signs, cracked concrete blocks, two-thirds of what look like a former playhouse of a rich little girl, a headless doll stuck in a window opening, three cement encrusted shoes of indistinguishable sizes mounted in a row on a shoe carrier, stacks of coiled wires, two piles of tires turning brown, and all sorts of unidentifiable trash, the whole mess surrounded by sacks of rotting garbage. The dump is a repetition of the depths of the azure seas surrounding Reggio.

Gino points east and says: “That road doesn’t lead anywhere. It ends down there around a curve among abandoned factories at a half-finished bridge. After that you see only walled fields of wild weeds bordering the sea … the symbol of the Mezzogiorno of Italy.” Then, abruptly, a few fields and gardens to the east are brilliantly golden in the rising southern sun, as if showing their best to me the visiting journalist. Even though the sea is close, this narrow part of the peninsula seems unlimited. The occasional touch of the wild is inevitably marred by improvised, semi-clandestine dumps. As Gino slows to a near stop I try to identify the objects filling an unmarked danger zone filled with rusted and gutted car bodies, wheelless motorcycles, crooked pipes now turned green, unidentifiable sheets of bent and moss-crusted metal from who knows what abandoned factory, former stereo sets, parts of bedsteads and yellowish mattresses, No Parking signs, cracked concrete blocks, two-thirds of what look like a former playhouse of a rich little girl, a headless doll stuck in a window opening, three cement encrusted shoes of indistinguishable sizes mounted in a row on a shoe carrier, stacks of coiled wires, two piles of tires turning brown, and all sorts of unidentifiable trash, the whole mess surrounded by sacks of rotting garbage. The dump is a repetition of the depths of the azure seas surrounding Reggio.

Gino stares at the alternating scenery and the passing fields he must have seen so many times that he hardly registers its reality. And he talks: “Unemployment is worse each day. Industries big and little shut down, bankrupt. Or they move abroad. The few open schools exist because city administrators have forgotten them. The former capillary health system is in chaos. The ‘ndrangheta controls the economy. Poverty is spreading and youth escaping to north Italy or abroad.” His words reflect the disaster so visible around us. Everything except the occasional surviving bit of wild confirms that the situation is even worse than his descriptions. The truth of the South lies much deeper.

“Why is the South so much poorer than the North, Gino?”

“Traditions. Organized crime. Mafia. Corruption. A way of life. And Gael, that is the story the new Radio Calabria Libera is broadcasting twenty-four hours a day to the region.”

“What’s that, Gino? Never heard of it.”

“It’s new. American, I hear. Another NGO. They’re springing up like mushrooms. You know what we call them here? The Ngo-isti. Calabrian-American Friendship Society or CAFS, American Friends of Calabria, White Scarfs For Progress, Blue Helmets, American Society For Defense of Human Rights, Society for Resistance. The most visible appears to be the International Committee For Liberation From Communism or ICLC. Do-gooders of all sorts. The message of all is the same: Down with Rome corruption! Down with Communistic Rome! A new Calabria for a new Italy! Resist! Resist! Make Reggio great again! A free Calabria!”

“Oh yes, certainly American … or their proxies. Expel them all!”

“But the people love them.”

“As always. Everywhere.”

I observe Gino Rocca’s silhouette, an agitated and rarely silent driver. I think he feels a sense of timelessness and the same pandemic loneliness of the deep South. A feeling of not even being part of the world. I begin to form an image of a frustrated Gino, hanging between revolt and submission. A face concealed behind the mask of furious action and his talking head, his mask which, I suspect, is the twin of his true face underneath. As if he were on the verge of finding an answer to the conundrum that has plagued him for years: to revolt against everything and opt for the old Italian temptation of anarchy or to succumb to the contradictory thought that his life is all illusion, in which case what does it matter what he does? Gino’s words remind me of another Munich summer lecture course by a visiting professor from Vienna. According to the scholar, Nietzsche had noted that philosophers never express their true opinions in their books because many such ideas are too complex for words. The summer professor posed the question whether such books are not written in order to conceal that which resides inside us? Maybe the true truth lies concealed in multilayered shrouds of ambiguity. Like Nietzsche who believed that every philosophy conceals another philosophy, every opinion is just a hiding place for other opinions and every word a mask covering other words. I’ve thought that those are difficult, maybe evil thoughts. (Walter Benjamin: We do not always proclaim loudly the most important thing we have to say. Nor do we always privately share it with those closest to us, our intimate friends, those who have been most devotedly ready to receive our confession.”)

Gino Rocca and his existential conundrum calls such reasoning to mind. Things here are so bad that Gino can’t find the words to describe the problems, despite his many words hurtling intractably through his rickety car and out into the indifference of the southern air. During a sudden silence I realize that he conceals a constant turmoil of emotions, that in this moment he is wondering just what the fuck is he doing with his life. What are we doing here anyway? Who am I in all this? The answer, he must have concluded, the meaning of the world and his place in it, will forever lie outside our grasp. The journalist that is me, he must imagine, knows what he’s doing down here. Everyone else seems rooted in something somewhere or in a home, a job, a family, a purposeful life. Everyone has a life plan. For Gino, happiness and love must seem to exist behind the closed doors and blinds along the streets of these towns outside the orbit of Reggio. Where whole families are concealed. Where women love their men despite all, and men love their families. More than anything Gino perhaps would like to be somewhere else with his family, any other place at all, but he is aware that he is as involved in his milieu as a lifer in a penitentiary in his, and in his every waking moment he realizes he has lost sight of a destination. I suspect he knows there is no security exit for him.

“You’re suddenly pensive,” I say. “What’s on your mind?”

“Sometimes I wonder how the fuck we’re to stop what’s going on up there in the mountains,” he says, pointing to the east. “I just hope our presence will be useful.”

Gino glances at me and then continues to stare intently at the rising hills. This, I think, is a good man. And he is alone. He is sick, too. His solitude is his illness. He must wonder if deep down everyone feels the same implacable solitude. If I too feel it. But I don’t believe he considers solitude as punishment. Sometimes solitude is peaceful. Gino has only his TV, his dedication … and his solitude which I think he coddles like a hypochondriac cuddles his manias. His solace might be a conviction that someday the whole world will become the same and that nobody will belong any place. Some days he must relish his solitude, court it, as if it were his true self. As if solitude were a virtue in a world in which organized society spoils things and makes people unclean. On the other hand, maybe he believes he is destined to wander in the world, forever a stranger. Since I tend to be like that too, I understand him. I know he hears solitude’s melody. For chronic solitude can become a companion.

Gino thinks aloud: “I’m certainly not convinced of our usefulness. But I would like to believe that my work is a mission and that the mission is accomplishable. But what choice do I have?” he adds, looking at me with a dreamy look in his dark eyes as if thinking of faraway places. In that moment I see that Gino Rocca conceals his reflective nature behind his mask of hyper activity, a mask underneath which powerful transformations are taking place. Though he tries to maintain a modicum of calm, it must be difficult for him to contain his desperation. That effort must confuse him because at the same time he must be conscious of an emotion of tenderness he’d surely once known which restricts and controls his anger. I wonder if he has come to think that such an emotion must eventually come down to pity and which fuels his solitude in the world. Genuine pity is a painful feeling for most people. Perhaps the capability of feeling pity distinguishes people one from the other. I sometimes see it in their eyes … its presence, or its absence. It’s the specific nature of the lonely look of solitude that I note. Like that of Oreste that day at Vanya’s. Each solitude is different. Like fingerprints … or DNA. Gino’s solitude must be his awareness of injustice that has made him so dedicatedly one-tracked. And homeless. Gino must have long thought that everybody has to have his own place in the world.

When Gino takes the Scilla exit toward the Aspromonte rising darkly to the east, an age-old Italian idiom comes to my mind. In Greek mythology, Scylla—Scilla in Italian—was a monster that lived and controlled one side of the narrow strait between the mainland of the peninsula and Sicily, just opposite its enemy, aggressive Charybdis, or Cariddi today, that controlled the other shore. The two sides were within arrow’s range of each other, so close that mariners trying to avoid Charybdis passed too close to Scylla … and vice versa. The Italian idiom “between Scilla and Cariddi”, still used today especially in the political world, has come to mean finding oneself blocked between two mortal dangers, the choice of either of which brings harm and destruction.

“What you’re about to hear is probably the most secret and explosive piece of information in these parts,” Gino begins, as he turns into the mountains.

For a while we drive in a weighty silence that intensifies as the narrow road begins to climb and a more genuine wildness materializes around us. I feel like a trespasser. My stomach muscles inexplicably contract when I see a sign for the Montalto area indicating that it is two thousand meters altitude above the seas.

Gino leans forward studying the terrain and suddenly turns from the road into a space hardly wider than a trail, winding among rocks, shrubs and then, abruptly, a wall of tall trees stops us. Scilla is far behind. Cariddi is another world. At a snail’s pace we enter a circular clearing from which several paths branch off in various directions into thick woods. Two black vans and three military-looking trucks covered with canvas are parked there haphazardly in the dirt and dried mud.

“What’s this place?” I ask.

“Welcome to the home of the Esercito di Difesa della Patria,” Gino says sardonically. “This is where the secret army, the new Gladio, is trained.”

“So the EDP really exists!”

“And I thought it was top secret,” he says in surprise. “Just goes to show you.”

“What do they learn here?”

“Soldier business. How to kill. Urban warfare. Explosives. You name it.”

“You know the history of Gladio, I suppose.

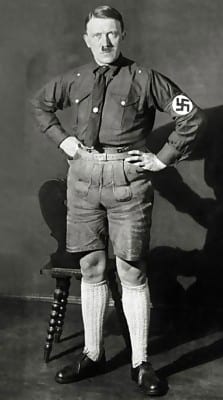

“Yes, I know about Gladio,” he says smugly, as if aware that he had the story of his life in his grasp. “The secret army organized by American Intelligence and NATO a half century ago to crush the European Communist parties … especially in Italy. But ostensibly a parallel army to fight the supposed threat of Soviet invaders of West Europe. But also to carry out terrorist acts against the Italian state … providing the pretext for tightened control over the country. Prime Mister Andreotti himself revealed the Gladio story in a speech before Parliament in 1990. But Gladio never died. Much of the world is still hostage to its strategy of tension … a ring of fear to justify state wars, state terrorism and military interventions.”

“I was at the G8 in Genoa,” I say. “They were there too.”

Gino looks at me, the surprise vivid in his eyes that I know what he’s talking about. We are both thinking the same thoughts: tension strategy thrives all over the world for manipulating and controlling public opinion: fear, propaganda, disinformation, psychological warfare, agents provocateurs … and false flag terrorist actions; that’s what super secret Gladio was up to in Italy; organizing terrorist acts and blaming them on Communists; spreading fear and then passing laws restricting the freedoms of the people. People fell for the propaganda of the threat of a Soviet invasion: the scary image of Russian Cossacks watering their horses in Vatican fountains.

Gino: “Gladio’s job was to eradicate leftism.”

“Gladio also trained its troops in the mountains,” I recall. “In the Abruzzo near Rome and in Sardinia—in places like this. Terrorist bombings followed. And leftwing terrorists—also manipulated by the CIA/NATO/U.S.A.—were blamed.”

Crazy how people never get it. The people are afraid. Their fear grows, more special laws are passed and thousands of leftists are imprisoned. Keep the populace afraid so that promises of security will be believed. Fear is the point. You create it with lies. That’s why the state suppresses dissent, for truth is the enemy of every authoritarian state. The state media defined Communists as the enemy. Anything is justified to crush them. Communism and terrorists and Islamic fundamentalists … and immigrants too. Gino knows all this.

“I still find it incredible that people in Italy, in Europe … in the whole western world … don’t know or maybe don’t want to know about Gladio.

“Right!” Gino says. “People don’t try to understand why terrorism. Or who the real terrorists are. Now that secret army is like reborn right here in Rhèghia’s mountains,” Gino repeats, staring out the window in such a dejected way that I don’t mention Parliamentary investigations of Gladio and the 300-page report on Gladio operations in Italy and its connections with the United States. People are ignorant of the detailed report that explains Gladio and blames the U.S.A. It shows that the massacres, bombings and para-military actions were organized or supported by shadowy men within Italian state institutions, by men linked to American Intelligence.

“A bomb inside the Banca Nazionale dell’ Agricoltura on Milan’s Piazza Fontana in 1969 marked the beginning of the strategy of tension,” Gino adds. “The Piazza Fontana massacre. Sixteen dead, fifty-eight injured. The bombing took place at the height of the biggest strike wave that Italy had seen since the end of WWII. Automobile and sheet metal workers were aggressive and militant. The bombing stopped the strike wave dead in its tracks. Then the police ran wild, hauling suspected leftist sympathizers in for questioning and intimidating their families, while the government passed emergency laws against suspected terrorists. This method of social control came to be called ‘the strategy of tension’, tension being a key factor in psychological conditioning. Police and the media blamed the Piazza Fontana bombing on a pathetic group of anarchists, the Bakunin Club, which had been penetrated by the Italian intelligence service. The railroad worker Giuseppe Pinelli and the male dancer Pietro Valpreda were accused. Pinelli was pushed to his death from a fourth-story window of police headquarters, while the mass media vilified Valpreda as a subhuman beast. More than twenty years after the fact, information emerged that the bombs of Piazza Fontana had been placed by GLADIO operating under the control of NATO intelligence, afraid the strike wave might lead to the entry of the Italian Communist Party into the government. Throughout the seventies and into the eighties the USA, NATO and Italian ruling circles were obsessed with keeping the Communists out of the Rome government.”

I tell Gino of an chance interview I had with the ex-chief of the CIA. After a lunch with my newspaper’s director in the Grand Hotel, William Colby—there for a conference—sat down next to me at the hotel bar. I recognized him from press photos. “We exchanged some bar talk about Italy before I revealed I knew who he was and asked him about Gladio … intended as a provocation. To my surprise he bragged that the covert action branch of the CIA after World War II built throughout Western Europe what in intelligence trade parlance were known as ‘stay-behind nets’. He said the Pentagon didn’t take a stand on the subject of the secret NATO stay-behind armies because it was not even questioned by the US press. The networks were clandestine, ready to be called into action as sabotage forces when the time came. ‘In 1951,’ Colby said, ‘the chief of the CIA in Western Europe sent me, then a young intelligence officer, to help build the stay-behind network. A secret army. All top secret back then. Our aim was to create an Italian nationalism capable of halting the slide to the left,’ he said as if speaking of ancient Greek history. When I remarked that they used right-wing terrorists to create it, Colby didn’t even blink. Gino, those people are really convinced of their exceptionalism.”

In that moment a big, powerful-looking man dressed in jungle green emerges from the woods and approaches us. A prickle of alarm careens down my spine and stops its race in mid-back where it remains for the long seconds before Gino says:

“This is Edoardo la Torre. You can trust him.”

“What do you want, Gino Rocca?” the man asks, leaning forward and peering at me and stroking his automatic weapon tenderly. “And who is this?” he adds nodding at me.

“You can trust him too, Edoardo,” Gino says gently. “Are you ready? Can we go back to town.”

Since Gino had not revealed the real purpose of our ascent of the Aspromonte, I had no inkling that the man standing near the driver’s side of the car with his weapon cradled in his arms would turn out to be one of the most complex, curious but conscientious persons I was ever to know, a soldier of fortune and member of the EDP, the Esercito della Difesa della Patria, the reborn Gladio. Without a word the huge figure of Edoardo climbs into the back seat.

The streets of bedraggled Reggio are still deserted. Gino parks on a cobblestone street near a piazza in the historic center. Chimes sound from nearby. Only a few lonely looking persons are visible on the piazza. From a side street echo faint sounds of music. A green grocer on a corner displays a few pale zucchini and a couple of purple eggplants. Silent women stand around the stalls. Stray poultry peck fruitlessly at the cobbles. Two dogs hanging around look lazily aggressive. The bigger one creeps toward me, probably smelling my fear. I walk closer to the Gino and Edoardo until the menacing canine gives up. Our footsteps reverberate off the thick stone walls that I suspect conceal a lifestyle different from anything I’m familiar with. What I imagine are the town’s usual colors have faded into a lifeless summery brown like the sands of Reggio’s filthy beaches lapped by polluted water.

Gino ignores the present crowding and crushing him. His very life—his past too—seems to languish in the still air. What kind of a past could a man like him have while his present couldn’t possibly hold any promises of future reward? It saddens me that I don’t know Gino’s reality. But how little we ever know about others. Like mine, his past is invisible. He must sometimes yearn for a return to what once was, a ‘make-Reggio-great-again’ kind of thing, which he must know was never anything special at all. His nostalgia for that past should have died when his present began but it seems to hang on. I can understand that. I see his dejected air and believe I understand that his fear that his former better life, now cornered in the darkest recesses of his memory like a feared disease, will never return. The process has sharpened his repressed anger at his native land. Uncertainty and threat have become his new present while his recent past fades out of his memories.

We slink through the narrow streets of the old town. Here and there in places where the sun has found its way to the cobblestones, sagging bougainvillea around a ground floor window struggles for survival. Vases holding dried plants are cracked and faded. The atmosphere is that of a dying city. People have given up trying to save it from the corruption and organized crime and dark political powers no one understands. We round a corner and stop in front of a small building that I think is a deconsecrated chapel. Hammering sounds are audible from within. A Mercedes 500 is parked on the sidewalk in front.

“Strange,” Gino says, pushing open the cracked door, “this place is usually barred.”

He enters, nervous and agitated. “I used to come here often, a social center then … until the city government cracked down on it, suspecting some political conspiracy … perhaps a cell of Reds. Local police know what this place is becoming—a political meeting hall … but have reported nothing.” Gino whispers that we are looking at a rehearsal of a theatrical group but that the NSP party officials up on the stage want to charge them for appropriation of public property and use it as a pretext to crack down on any kind of public meetings.

Edoardo snickers.

Gino and I stand in the rear and watch Edoardo move forward. On one side of the low stage stand a long plastic table and several chairs. A row of seats have been ripped from the wall and placed facing the front, behind which there are some ten rows of benches and chairs. When a flute sounds, a middle-aged woman wearing a dirty smock stands up on center stage and begins reciting. My eyes fix on electoral placards hanging across the back wall of the stage. Along the sidewalls of the make-shift theater, political streamers droop to the floor. Two tables near the door are loaded with stacks of brochures.

Edoardo steps up onto the stage. Gino and I follow a few steps behind. The workers wearing black overalls stop hammering and stare at him, huge in his jungle attire. The music stops. Someone leads the woman to the wings. Two men in jackets and ties holding notebooks and pencils turn toward us. A squad of three men dressed in the ritual black stand to one side, nudging each other and snickering.

“The shit is flowing like lava from Mount Etna,” Gino mutters.

“You mean from the Aspromonte,” I say, glancing meaningfully at Edoardo. “Gladio! Never thought to meet one of its soldiers down here.” Gino grins weakly. His visit here in the social center must be an act of nostalgia. Maybe he thought he would find here a fragment of his past, from times when people did normal things. He must have thought if things here were still the same, not all was lost.

“What the fuck is going on here?” Edoardo suddenly shouts from near the stage. Silence echoes through the hall. “This was once our social club. Before that it was a church. Now it’s closed.”

“Right! This is no longer public property,” one of the men in civvies says weakly.

Edoardo waits.

The other, a young guy, with short slicked down hair and a wide red necktie, is wearing a black armband inscribed with the letters N.S.P. in white. “It belongs to the National Socialist Party now,” he says.

“And what do your Separatist friends say about closing this cultural center?” Edoardo taunts. “This place belonged to the people.”

The young man with the armband looks at him uncertainly, shuffles the papers in his hand, and mutters, “Who cares what they think?”

Edoardo moves toward center stage and stops in front of the two men. Calmly he examines each, as if undecided how to react. Then, in a soft voice, he says, “I’m going to report this to the police, then we’ll see.”

“We are the police,” red tie says, now aggressively.

“Then why don’t you ticket that car parked outside on the sidewalk?” When the other doesn’t answer, Edoardo looks into the man’s eyes and for some reason seems to feel sympathy for him; he seems to know the pompous little man is a coward.

“And what’s your name?” Edoardo asks one of the NSP men, a tall, slim youth standing near him.

“Gaetano.”

“Gaetano?”

“Gaetano Bolzoni. Why?”

“You’re a decent looking kid. What are you doing with this gang of hoodlums?”

“Just making a living. You have to work somewhere.”

“He’s a fucking sissy,” interjects a big mean-looking guy.

Edoardo turns to the obvious bully of the group. “And what’s your name, if I may ask?” he asks the man sweetly.

“Cesare Pinelli! What’s it to you?” the other says with a snarl.

“And where might you be from, Cesare?” Edoardo asks, now syrupy. I grin as I write the name in my notebook, certain that more action is to come.

“Palermo,” the other retorts. “And I know how to take care of you.”

“Cesare, you’re a real sneaky guy … a bully too.” Edoardo says. “But you’re also a coward. Oh, oh, Gino, Gael, we’d best get the fuck out of here before they beat us up too. Cowards are dangerous … you never know what they’ll do next,” he says facetiously as a parting salute to the three men in black, before whirling and slamming his huge fist into the bully’s belly. The big guy bends double and collapses in a heap. Edoardo stands over him for a moment waiting for a reaction. Only moans sound from the man coiled at his feet.

Back on the street, we turn a couple of corners and stop in front of the cathedral and chat about what had happened. “You know, I’m always amazed at the differences between people everywhere,” Edoardo says. “I see it immediately. You can see that guy Cesare shooting off his mouth like he did is an evil person, yet right beside him stands that kid, Gaetano. You look at him and you see innocence. Simply graceful, the innocence in the way he looked at me. Crazy! And to think we all come from the same origins! Or actually I don’t know where we come from.”

He looks at me as if wanting to hear how I would respond to his ruminations.

“Years ago, I lived in Germany,” I begin hesitantly, uncertain as to what I want to say on the question of good and evil. “I remember a story I read by a German writer named Heinrich von Kleist. The story is about a marionette theater like one I used to go to in Munich. It’s like a miniature opera house. I went to see the magic performed there. I’ve always wondered how they make the puppets’ movements so graceful. The more lightly they touch the stage boards, the more graceful they appear. Puppets just graze the boards or don’t touch them at all. At that point the writer introduced a bear into his story in which no puppets appeared. The narrator, an expert fencer, relates how he faced a chained bear which he was dared to try to touch with his rapier. The bear parried each of his thrusts with the slightest of movements and didn’t react at all to his feints. Its every movement was graceful, free of wasted movements. A studied grace.”

“So what does the story mean?” Edoardo asks, leaning closer toward me and peering into my eyes.

“Well, Kleist said that grace appears most easily and perhaps secretly in people and animals and organic forms that are unaware of their grace … or that grace is a consciousness which those without that grace cannot grasp. His point, I think, is that in the puppet or in a god, grace is the same as goodness.”

“God?” Edoardo says, as if alarmed. “You said God. My mother who was very religious had her favorite bible quotes for most everything. She spoke a lot about the tree of knowledge of good and evil. I never understood when she said that God knows that the day we eat of the tree of knowledge our eyes will be opened and we too will be like gods, That we will know good and evil, she said.”

“So what’s wrong with that?” I interject, examining the cobbles under my feet. “Aren’t we a little like gods after all?… now that we know that God is dead?”

“God is dead?! … Well, I asked about good and evil because I’d just had the thought that if that guy Cesare were a bit less mean, I could pity him,” Edoardo says. “Yes, definitely, he needs pity.”

I look up at him, astonished. And wait for more. He looks as if he wants to add something but instead he turns away and starts back toward the Ford. By now I’m coming to understand that when one hardened man feels pity for another like himself … that it seems to count for much more than the pity of those who only preach pity. Edoardo made me feel this truth.

A blue police car is parked just in front of Gino’s old Ford, with a ticket hanging under a windshield wiper.

About the author

Our Senior Editor

based in Rome, serves—inter alia—as our European correspondent. A veteran journalist and essayist on a broad palette of topics from culture to history and politics, he is also the author of the Europe Trilogy, celebrated spy thrillers whose latest volume, Time of Exile, was recently published by Punto Press.

“Oh yes, we survive … as we have for thousands of years. Yes, we survive. The Premier himself—like all the premiers before him—promised order and security in the Mezzogiorno. Now, the Fascists in the city and a secret army in the mountains are vying for the right to execute his orders … and to kill him too. Create order! And killing enemies to do it. Killing refugees and killing Italy. Tonight I’ll take you out. There’s no moon. No hard winds, the sea calm. Though clandestine immigrants land here in lesser numbers than in Sicily, the beaches will be swarming with speedboats and police tonight. You’ll see. Our gallant forces will line the coastline to protect the homeland from the invader.”

“Oh yes, we survive … as we have for thousands of years. Yes, we survive. The Premier himself—like all the premiers before him—promised order and security in the Mezzogiorno. Now, the Fascists in the city and a secret army in the mountains are vying for the right to execute his orders … and to kill him too. Create order! And killing enemies to do it. Killing refugees and killing Italy. Tonight I’ll take you out. There’s no moon. No hard winds, the sea calm. Though clandestine immigrants land here in lesser numbers than in Sicily, the beaches will be swarming with speedboats and police tonight. You’ll see. Our gallant forces will line the coastline to protect the homeland from the invader.”

The Greanville Post is a publication of The Voice of Nature Network, Inc., (VNN) a not-for-profit organization.

The Greanville Post is a publication of The Voice of Nature Network, Inc., (VNN) a not-for-profit organization.