New Strategic Calculus for the Balkans (II)

Andrew Korybko (Russia)

(Please refer to Part I in acquiring the necessary background information in understanding the Central Balkans concept).

3 Key Characteristics Of The Central Balkans

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]ince the general idea and genesis behind the Central Balkans have been discussed, it’s now time to turn towards their three most important strategic characteristics:

Lead From Behind Agitators:

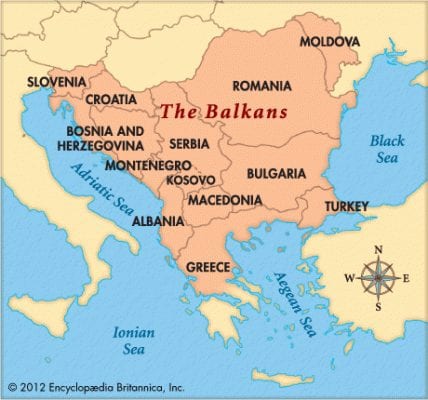

Like it was mentioned earlier, newly crowned NATO members Albania and Croatia continue to pose the greatest threat to the Central Balkans. Croatia used to be the primary vehicle for unipolar military activity in the region during the 1990s, but this role was ultimately transferred to Albania for dual deployment against both Serbia and Macedonia. As it stands, Croatia appears to be suitably prepared for returning to its Lead From Behind anti-Serbian role, which one can clearly see by its election of a former high-level NATO information officer as President. Although a largely ceremonial post, it’s symbolic in underscoring the affiliation that the country’s political elite have with Euro-Atlanticism (unipolarity), and with the US’ current support of ultra-nationalist governments and neo-fascist movements, it shouldn’t really stun anyone that Croatia’s new leader is now openly paying tribute to pro-Nazi World War II collaborators. The nightmare scenario for Serbia’s international security is for Albania and Croatia to coordinate any forthcoming destabilizations against the country, and unrest in Serbia or along its borders could also impede the construction of Balkan Stream, at the very least of its consequences.

Triggers:

There are two triggers that can most strongly undermine the stability of Serbia and Macedonia:

* Bosnia

Per the earlier explanation of Republika Srpska’s security significance to Serbia, any provocations inside or along its borders would tangentially also present a threat to Serbia itself. A constitutional crisis over internal power arrangements and federative sovereignty inside of Bosnia could be the catalyst for drawing Repubilka Srpska, and by extension (whether direct or indirect), Serbia, into a larger conflict (the ‘Reverse Brzezinski’ as applied to Belgrade). Not only that, but an externally directed terrorist war could be cooked up (just like in Macedonia) to inflame identity tension between Bosnia’s constituent members, which would then usher in the national crisis purposefully constructed to temptingly invite some form of Serbian response and/or involvement, thereby sucking it into an American-planned trap.

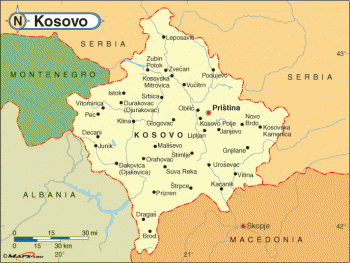

* Greater Albania

The most pressing threat to Serbia and Macedonia’s security and the issue with the greatest potential to destabilize the entire region is the looming specter of Greater Albania. Serbia fell victim to having the most emotionally integral part of its country stolen from it, occupied, and turned into a weapon against the rest of the rump state the last time this was attempted, and it remains a distinct possibility that something similar can happen to Macedonia as regards its entire western and most of its northern periphery.

Additionally, Serbia also faces a new threat from Greater Albania, and that’s ethnic violence in the Albanian-populated Presevo Valley and Sandzak regions, with the first-mentioned being intentionally stoked by a ‘spill over’ from northern Macedonia. Kumanovo just so happens to be close to this region, hence why the terrorists selected it as their base in the event that the order was given to split their forces north and simultaneously attack Serbia on 17 May (the day the Macedonia Color Revolutionaries and Unconventional Warriors were to symbolically unite in their regime change aggression).

Taking it further, even the Greek region of Northern Epirus could potentially be brought into the tumult of Greater Albania, thereby destabilizing all three Central Balkan countries, but potentially providing an urgent impetus to expedite their multipolar integration with one another in standing united against this threat.

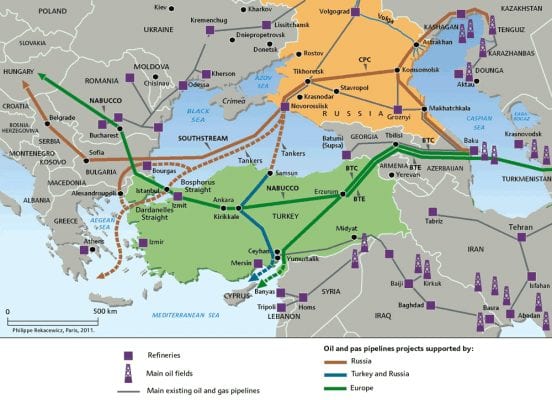

Balkan Stream:

[dropcap]P[/dropcap]erhaps the most critical characteristic strategically uniting the Central Balkan states is the Balkan Stream project, which implicitly aims at promoting multipolarity in the region and potentially even taking it as deep as the heart of the EU itself. Should the project reach fruition and the US’ current destabilization plans fail (the Color Revolution attempt in Macedonia and the provocations to incite a regional war around the idea of Greater Albania [just as Greater Kurdistan is being primed for deployment in the Mideast]), then the logical consequence would be that the Central Balkan countries serve as the springboard for multipolarity’s expansion into the European continent.

Balkan Stream is thus more than just a pipeline – it’s a strategic concept of sub-regional integration that’s meant to defy the unipolar dictates of the US’ EU proxy and achieve the long-term goal of liberating Europe from unipolar hegemony. Due to the fact that the Central Balkan countries are the physical vanguard of this far-reaching and profound vision, the US is prioritizing its latest destabilization attempts against each and every one of them, hoping that at least one of its plots takes root after having desperately sowed so many seeds of chaos in the past couple of months (capitalizing off of existing factors) to offset this relatively unexpected multipolar counter-offensive.

Multipolar Solutions

The Central Balkans are currently the latest front in the New Cold War between the US and Russia, or better put, between the unipolar and multipolar world visions. Washington has recently redirected its external meddling activities in order to focus on destabilizing this particular sub-region and sabotaging its march to multipolarity, owing to the previously overlooked vulnerability that the Balkan Stream provides in countering unipolar control all throughout the continent. It is thus of the utmost importance that appropriate defensive policies be implemented in order to reinforce the Central Balkans’ resistance to the US’ aggression and secure the multiopolar counter-offensive currently taking place in the region.

The following are the proposed solutions for solidifying the multipolar vision of Balkan Stream:

Clearly Elucidate Multipolar Aims:

The Central Balkans and their strategic Russian and Chinese partners must publicly articulate their multipolar vision for the region, as such a strong and unified voice would send a global message about the intentions of the non-West. It’s not to suggest that the actors must openly call for overthrowing American control over Europe, but rather to highlight that there are non-EU development trajectories and partnerships that can be just as, if not more, beneficial than working with Brussels. It may even come to pass that the Central Balkans becomes the first flank in a wider European revolt against unipolarity, but in order for this to happen and for the region to serve as a rallying point for the rest of the continent, its anti-hegemony message must be clearly expressed. Political pragmatism and multipolar partnership, not unipolar partisanship and chaotic division, are central themes in conveying this concept.

Institutionalize And Intensify The Balkan Corridor:

The complementary Russian and Chinese infrastructure projects running through the region form the basis around which the Balkan Corridor can be constructed, and the first step towards its formalization is to unveil a multilateral framework between its members. This would serve as an organizational mechanism for coordinating integrational policies between Russia and China on one hand, and Serbia, Macedonia, and Greece on the other, and it could possibly be expanded to include Hungary and Turkey as observer members, if not full-fledged participants. The key purpose is to bring together policy and decision makers, security specialists, and economic actors in hammering out joint details for further cooperation and the intensification of their multilateral partnerships.

Unite The Central Balkans Against Greater Albania:

As much of a threat that Greater Albania is, it also provides an historic opportunity to unite the Central Balkan countries in opposing its terroristic actualization. The existential danger that this US-supported irredentism poses for Macedonia rightfully incites fear in both Belgrade and Athens, as neither of them want a partitioned and failed state along their borders, to say nothing of their own domestic vulnerabilities to the ethnic terrorism directed by Tirana. The US and Albania have clearly demonstrated that they’re taking concrete action in agitating for Greater Albania, so it’s appropriate for the targeted states to tighten their military and strategic ties in defending against it. While Greece’s NATO membership may pose an obstacle in this regard, Serbia and Macedonia aren’t constrained by this limitation and can thus work as closely as they deem necessary in countering this threat. Not only that, but they can also expand their de-facto military alliance to include Russia, which could then provide military, political, and technical support to their countries’ anti-terror and counter-Color Revolution operations in the same manner as it’s been proudly doing for Syria over the past four years.

Emphasize Russia’s Connections To The Region:

Russia has deep cultural, linguistic, religious, and historical connections to the Balkans that it can capitalize upon in promoting Balkan Stream and gaining soft power inroads in Serbia, Macedonia, and Greece. These unique asymmetrical factors perpetually tether the Central Balkans to Russia, but more work must be done in order to strengthen these bonds and make the ‘Russia factor’ a significant part of those countries’ national identity and psyche. The deepening of emotional ties can enhance the effectiveness of multilateral soft power expressions between Russia and its Central Balkan partners, thereby providing a stable foundation for the future expansion of their relations and increasing their larger strategic cohesion.

Concluding Thoughts

Great Power competition over the Balkans has historically served as one of the engines of European politics and has been among its most widely recognized features for centuries. Back then, multiple empires were jostling for influence and counter-balancing one another, but the situation has remarkably simplified in the current day. Nowadays only one empire remains and that’s the United States and its unipolar allies, which have been doing all they can to completely swallow the region over the past two and a half decades. Serbia and Macedonia are the only two regional holdouts remaining, and they form the core of a reconceptualized Balkan region, the Central Balkans, that’s partnering with Russia in staging a multipolar counter-offensive against this aggression. The geopolitical liberation that Balkan Stream would bring to the region, and quite possibly all of Europe, makes it one of the most globally impactful projects currently under construction, and it’s arguably central to Russia’s grand strategy in dismantling unipolarity.

The conceptualized creation of the Central Balkans assists one in more easily understanding the regional geopolitical arrangement in the context of the latest round of the New Cold War. Additionally, it holds the exciting possibility of evolving from an intangible concept to a concrete reality by serving as an organizational platform for energizing closer integration between its members. The institutionalization of the Balkan Corridor and its accelerated strategic unification in resisting the threat of Greater Albania is expected to facilitate the creation of a critical mass of multipolarity that can flip the regional initiative against the destabilizing unipolar forces. Thus, because it signifies the first step in a larger counter-offensive against the American occupation of Europe, Russia’s support of the Central Balkans and their strategic convergence into an integrated entity is arguably one of the most pivotal multipolar processes in the world today, and it could potentially transform into a battering ram for breaching the US’ unipolar citadel in Western Eurasia.

[box] Andrew Korybko is the political analyst and journalist for Sputnik who currently lives and studies in Moscow, primarily for ORIENTAL REVIEW. [/box]

[printfriendly]

Remember: All captions and pullquotes are furnished by the editors, NOT the author(s).

What is $5 a month to support one of the greatest publications on the Left?