We offer several takes on a film with some of the most thought-provoking premise in a long time. By touching upon the taboo issue of class, director Blomkamp parts ways with the vacuity and silliness of most action flicks, or Hollywood fare in general, but there’s still too much frantic movement devoid of substance in this blockbuster to make Elysium a truly great film. See what four perceptive critics, Dave Walsh, Rob Kall, Chris Mandel, and Jonathan Kim, have to say.—PG

We offer several takes on a film with some of the most thought-provoking premise in a long time. By touching upon the taboo issue of class, director Blomkamp parts ways with the vacuity and silliness of most action flicks, or Hollywood fare in general, but there’s still too much frantic movement devoid of substance in this blockbuster to make Elysium a truly great film. See what four perceptive critics, Dave Walsh, Rob Kall, Chris Mandel, and Jonathan Kim, have to say.—PG

¶

(1) By David Walsh, wsws.org

Neill Blomkamp’s Elysium: To have or have not

The principal challenge in writing about a film like Elysium is to make neither too much nor too little of it.

Neill Blomkamp, the South African-born director (District 9, 2009), sets out certain provocative premises for his new film. By 2154, according to a title, the earth’s “wealthiest inhabitants” have “fled” to an orbiting space station, Elysium, some twenty minutes away by space shuttle. There, under sunny skies, gleaming mansions with luxuriant lawns and swimming pools prevail. Everything is light and elegant and clean. Medical science has developed equipment (Medi-Pods) that repair broken bones and cure even the most lethal diseases instantly.

The earth (whose scenes were shot in Mexico City), on the other hand, resembles a giant polluted, overcrowded slum. Its inhabitants are prevented, as undocumented “non-citizens,” from entering the paradise in the sky. They have little or no access to elementary social services such as health care. Police-state methods prevail, with armed robots controlling and brutalizing the seething, poverty-stricken population.

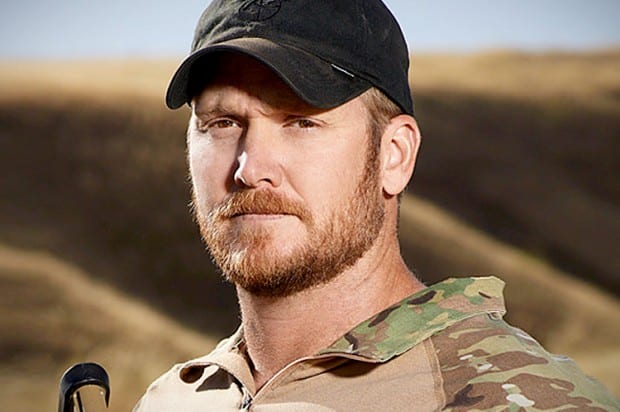

Max Da Costa (Matt Damon) works in a factory owned by Armadyne, the conglomerate that has built Elysium. An industrial accident, due to the company’s ruthless speed-up and drive for profits, results in his being contaminated by radiation and given five days to live. Much of the film is taken up by Max’s attempts to reach Elysium and provide himself with a cure for his condition.

Max’s predicament and his struggle to stay alive intersect with a crisis on Elysium, where Delacourt (Jodie Foster), a fascist-minded government official in charge of “Homeland Security,” who uses a vicious mercenary (Sharlto Copley) to liquidate “illegal immigrants” arriving from earth, is planning a coup that will place her in power. She justifies her plan on the grounds of the need to “protect our liberty.” At a certain point, Delacourt has a powerful motive for getting hold of Max and the information he (literally) carries in his head.

Max also encounters a childhood friend and former sweetheart, Frey (Alicia Braga), with whom he shares important memories. She too has compelling reasons for reaching Elysium: to obtain medical care for her daughter, suffering from an advanced stage of leukemia.

The events unfold in a violent, dense fashion.

There are numerous interesting things here: in particular, the focus on social inequality and its connection to political reaction and repression. In Elysium, as in life, the defense of the elite and its immense wealth requires intense violence against the disenfranchised, impoverished mass of the people. The references to Homeland Security, “Big Brother”-type surveillance, mercenary-like contractors, the plight of the undocumented, industrial murder, corporate corruption and malfeasance and anti-democratic conspiracies have an obvious significance. The events of the past two decades did not pass unnoticed, even in artistic circles.

Blomkamp grew up in South Africa during the latter stages of the struggle against the apartheid regime and attended film school in Vancouver, his current home. He seems a bit distant from the contemporary American film industry and its stifling, stagnant atmosphere, and thus capable of allowing realistic elements to enter into his work. A colleague explained, “He [Blomkamp] grew up in a racist, fascistic empire, watched it be overthrown, collapse into chaos, all while walking to school every day. Imagine the impression that leaves on you.”

Elysium has elicited a well-deserved venomous response from ultra-right commentators, who have referred to it as “Matt Damon’s Sci-Fi Socialism” and “socialist trash,” along with other insulting phrases. A spokesman for the right-wing Media Research Center told Fox News, “This is just the latest of several Hollywood movies this year to try and co-opt Occupy Wall Street plotlines into their films.”

Other media outlets have somewhat more objectively registered the film’s concerns. The Associated Press headlined a piece, “In Elysium, a cosmic divide for rich and poor.” The Los Angeles Times wrote of “Inequality at the movies.” In its review, Variety asserted that Elysium advances “one of the more openly socialist political agendas of any Hollywood movie in memory, beating the drum loudly not just for universal healthcare, but for open borders, unconditional amnesty and the abolition of class distinctions as well.” When was the last time Variety used the word “socialist” in reference to a major studio film?

Blomkamp told the LA Times that sections of contemporary Johannesburg, along with Bel-Air and Beverly Hills in the Los Angeles area, inspired his vision of Elysium. He commented to ScreenCrave, “I don’t think the film is speculative science-fiction. It’s so much more a metaphor for today in my mind.”

In an interview with Reuters, Matt Damon noted that the film’s premise was not far-fetched: “If you look at the difference between the bottom billion people on planet Earth and the top 10 million, the contrast is as stark as living on a space station and living in a third world urban centre.”

Blomkamp further explained to the Times, “Most of the time I just walk around annoyed. Would I describe myself as relatively happy, I suppose, but society gets to me. … If there isn’t a deep core reason for a film existing, what is the point? … For me to be known as a filmmaker that makes films that have a point, I’m stoked.”

It is to the filmmaker’s credit that he has his eyes open and thinks about the way the world is. (An ominous score, by Ryan Amon, and some impressive special effects make their contribution as well.)

Elysium, as a result, has some genuinely moving moments. The factory sequence in which Max receives his fatal dose of radiation is effective and convincing. The unfairness of Frey’s situation, her child dying while the affluent receive the most advanced medical treatment without having to think about it, is compelling.

However, such moments are the exception. Much of Elysium takes the form of a relatively tedious action film, dominated by a great deal of noise and mayhem, to no great effect. There is hardly a single figure who deviates from his or her predictable course. The dialogue is largely uninspired, and uninspiring. The exposition of the complicated plot, given at top speed by the characters, often seems awkward and unconvincing.

Spider (Wagner Moura), a Che-like figure, and his entourage seem almost entirely extraneous, except as a device to move the unlikely story forward. Foster’s Delacourt and Armadyne chief John Carlyle (William Fichtner) are so icy, villainous and without nuance that they might well have stepped out of a comic book. The scenes of the Los Angeles slums have, at times, that almost hysterical, inauthentic look one associates with a dark and skeptical view of humanity. Generally speaking, cartoonishness never helped anyone.

Perhaps most damagingly, Max is transformed from an individual whose situation shows dramatic promise into, alas, a conventional, unreal “superhero,” possibly the most boring of all fictional creations. As a consequence, one loses a good deal of interest in his particular fate, and even his final act of self-sacrifice is largely unmoving.

One of the difficulties is that Blomkamp has chosen to reproduce identifiable social and political elements of contemporary life without seriously turning his attention to the content of everyday life, to the drama of it, to its relationships and emotions. Elysium presents a peculiar combination of accurate physical and institutional facts, on the one hand, and contrived, overblown, schematic relations between its human figures, on the other.

Both Blomkamp and Damon have gone out of their way to deny any particular social message in the film. “The first order of business for a big summer popcorn movie is to make a kick-ass movie with great action,” says the actor. Blomkamp told the LA Times, “To be pigeonholed into political films, I would put a gun in my mouth if that’s how my career ended up.” No artist wants to be pigeon-holed, but the director’s over-reaction reflects an accommodation to a retrograde industry climate.

It is not astonishing, one supposes, given the pressures that a $100 million budget inevitably generates, that the filmmakers seek to “reassure” potential audience members that nothing much will be asked of them. Not astonishing, but not terribly worthy either. Elysium’s marketing is some reflection of its production: there is a pandering here to preconceptions about what an audience will or will not accept. In my own view, Blomkamp has weakened his film and made it less appealing to audiences through his insistence on dull, pumped-up action sequences. Hollywood at one point made enormously popular and insightful films that were something other than “big summer popcorn movies.”

Without offering excuses for the filmmakers’ failings, who, after all, do present some intensely intriguing material, one has to take into account as well the general political situation. Although many are only waiting for the other shoe to drop, there has not yet been a major social explosion in response to the catastrophic social inequality and attacks on the lives and livelihoods of millions. That remains the decisive issue, both for social development as a whole and art in particular.

______________________________________________

(2) By Christopher Mandel

The Future According to Elysium

Neill Blomkamp’s blockbuster, Elysium creates a disturbingly realistic vision of the future.

Last weekend director Neill Blomkamp’s Elysium came out in theatres. The film serves as de facto sequel to Blomkamp’s breakthrough District 9 which was nominated for a “best picture” Academy award in 2009. This article is not meant as a review but rather an analysis of the futuristic setting of the film. That having been said, let me just say that my opinion is similar to the bulk of reviewers. The film is quite good, but somewhat disappointing given the brilliance of its predecessor.

Perhaps the best element of the movie is its well crafted vision of a worst-case scenario (let’s hope) for the future of humanity. Most critics are treating the setting as a heavy handed analogy for our current state, but if you look carefully at the various elements of Blomkamp’s 2154, much of his vision is disturbingly within the realm of possibility.

The central theme of Elysium is class. The world features two distinct classes: the ultra wealthy citizens of Elysium, an orbiting paradise of green lawns, mansions, and high-tech regeneration beds that can reverse aging, reconstruct mangles limbs, cure disease, and even bring back the dead. This medical technology may strike viewers as complete fantasy, but the reconstruction of complex tissues has already been accomplished in tests and is currently being developed (although it is a bit unrealistic to suggest such medical marvels will be possible without a doctor on hand and take less than a minute!).

The citizens of Elysium are a ruling class. They enjoy monopolistic control the political bodies, military, and police. They are also the primary movers and shakers in the market place. Nevertheless, their primary relationship to the non-citizens stuck on Earth is not based on exploitation, but avoidance. Blomkamp’s world is not based on a Marxist critique of capitalism where the owners exploit the workers. 2154 is even worse. The majority of Earth dwellers simply aren’t needed in the marketplace at all, and most Elysium citizens would prefer to be shielded from the sad ugliness far below them.

The citizens of Elysium are a ruling class. They enjoy monopolistic control the political bodies, military, and police. They are also the primary movers and shakers in the market place. Nevertheless, their primary relationship to the non-citizens stuck on Earth is not based on exploitation, but avoidance. Blomkamp’s world is not based on a Marxist critique of capitalism where the owners exploit the workers. 2154 is even worse. The majority of Earth dwellers simply aren’t needed in the marketplace at all, and most Elysium citizens would prefer to be shielded from the sad ugliness far below them.

Elysium was created so the elite could escape an overpopulated planet, stricken with underemployment and environmental collapse. Blomkamp cleverly uses subtle imagery, such as an entirely brown African continent floating past the window of a spacecraft to tell the ecological story. Blomkamp seems to understand that he doesn’t need to explain the details, anyone who has read an article about climate change or even the descriptive placards at the zoo can easily fill in the gaps.

One of Elysium’s many robots. by PatLoika

One of Elysium’s many robots. by PatLoikaOne element of this motion picture that annoyed me as I left the movie theatre was the main character’s job. Max gets paid a low wage to stand in one place, periodically pushing a button in a robot factory. “Why in the world would a robot factory have unskilled laborers?” I thought. “Wouldn’t the first line of super robots coming off the line replace the workers?”

In his recent book “The Future,” Al Gore introduces the term, “robosourcing.” Economists have been discussing the effects of automation on labor and class since the dawn of the industrial age. The fear has always been that machines would dominate production to such a degree that there wouldn’t be enough jobs for humans to fill. Thankfully, in the industrial age this never happened, the technology always managed to create enough skilled jobs to offset the loss of low skilled roles. Now in the information age there is “robosourcing.” As artificial intelligence and robotics advance, the proportion of jobs which machines can fill is growing exponentially. In a modern factory, it simply doesn’t take very many people to build a car because robots do most of the work. Have you ever used a self checkout stand at a grocery store? Do you hire an accountant every April, or let your computer do your taxes? Right now in 2013, there are even computer programs writing news stories and composing symphonies!

The reason our hero Max works in a factory is because in the world of Elysium, the market for manual labor is so utterly bent in favor of the employers, that hiring Max is cheaper than building a robot to push buttons all day. In Blomkamp’s world, robots haven’t replaced the working class, they’ve replaced the middle class. They serve as soldiers, police officers, and parole officers. On Elysium technology has even replaced doctors.

Most interestingly is the role of AI in politics, law, and infrastructure. In Elysium, machines haven’t literally taken control, as is the case in the Matrix and Terminator series’ but they are more than powerless tools; the computer network running the space station defines everyone’s legal status, and by extension, destiny, in its database. Hence, a coup d’état can be achieved simply by telling Elysium’s computer system to change the identity of the president, and society itself is rebooted when the network is rebooted.

Elysium is a violent, summer sci-fi flick; it is not a footnoted dissertation on present trends and probable outcomes. Many of the Blomkamp’s ideas are pure make-believe and extremely unlikely (single-person space ships the size of cars?). But most of the defining characteristics of the film’s world are realistic conjectures based on present trends. This world, although a bit exaggerated perhaps (and certainly more action packed!), is possible. Let’s hope it’s not the one we pick.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Author’s Website: http://www.cloudlessrain.net/

Christopher Mandel is a writer, activist, musician, and Sunday school teacher in Denver, CO. He was a dedicated organizer in the Occupy movement and published his memoirs of that experience as MY OCCUPY: AN ACCOUNT OF ONE PERSON’S ADVENTURES IN THE OCCUPY MOVEMENT.

_________

(3) Rob Kall, OpEdnews

| Movie Review: Elysium; It Will Make Your Blood Boil |

|

By Rob KallI watched Elysium last night. It was successful. It made my blood boil and my teeth clench. The movie delivers a powerful message. We are already living in a hellish world where the elite and powerful are living lives of luxury off the backs, off the deaths of the 99.9 percent. It’s no wonder that this movie has been panned by so many mainstream critics. To be honest, this is not a perfect movie. It is made to pander to the tastes of today’s movie-goers, with far more violence than necessary to support the story. But this is a movie worth seeing. Without spoiling the plot, I can tell you that this movie shows the banal evil of the ruling, moneyed class, the brutal treatment of workers, the dehumanization and, beyond militarization, robotization of the police– police programmed to be cruel and inhuman. The defense secretary, played by Jodie Foster, is a brilliant but lethal psychopath. The head of a military manufacturer is a despicable sociopath who sees worker fatalities as annoying production line slow downs. But they hire an earthbound psychopath to do their dirty work. In the movie Elysium, the people on earth are a down-trodden, hopeless lot. The people of Elysium live on an orbiting habitat that supports 250,000 people, with houses selling for $250 million and up.  As you’ve probably concluded , the movie Elysium throws some futuristic trappings on the actual situation that exists in the world right now. Watching the contrast between the lives of the elite and the rest of the people on earth is what made my blood boil and my teeth gnash. Spoiler alert. Reading beyond this point will give away some of the plot developments. Matt Damon plays the hero of this story– a reluctant hero who accepts “the call” because he has no other choice. He has been exposed to radiation that will kill him in five days. Because of his dire situation, he seeks a very high risk solution with very low odds for success. That solution involves violating all kinds of laws of Elysium. As he embarks on this journey we learn that the elites who live on Elysium, a massive space station with green verdant lawns, waterways and clean air, control the laws and life on the surface of the planet. I’ve long believed that it will take heroes and heroines who are literally dying, people who know they have a short time to live, to engage in revolutionary acts of courage, standing up to the machine, fighting for justice and humanity. That’s what Matt Damon’s character does in this movie. There are many wisdom sources that say that it’s not the destination, it’s the journey. That’s true for this movie. The end is not really realistic or satisfying. It does show that the people take the tools for healing the sick back from the billionaires on Elysium. It does show that the people of earth are all made whole, treated equally. But as most Hollywood stories go, this one also portrays the solution as one resolved by a lone hero. Showing a courageous soul who is willing to sacrifice his life is a good example. But Howard Zinn and Woodie Guthrie have both said that it will take millions of small acts to save the world. Here’s what Zinn said in an interview I did with him: As you’ve probably concluded , the movie Elysium throws some futuristic trappings on the actual situation that exists in the world right now. Watching the contrast between the lives of the elite and the rest of the people on earth is what made my blood boil and my teeth gnash. Spoiler alert. Reading beyond this point will give away some of the plot developments. Matt Damon plays the hero of this story– a reluctant hero who accepts “the call” because he has no other choice. He has been exposed to radiation that will kill him in five days. Because of his dire situation, he seeks a very high risk solution with very low odds for success. That solution involves violating all kinds of laws of Elysium. As he embarks on this journey we learn that the elites who live on Elysium, a massive space station with green verdant lawns, waterways and clean air, control the laws and life on the surface of the planet. I’ve long believed that it will take heroes and heroines who are literally dying, people who know they have a short time to live, to engage in revolutionary acts of courage, standing up to the machine, fighting for justice and humanity. That’s what Matt Damon’s character does in this movie. There are many wisdom sources that say that it’s not the destination, it’s the journey. That’s true for this movie. The end is not really realistic or satisfying. It does show that the people take the tools for healing the sick back from the billionaires on Elysium. It does show that the people of earth are all made whole, treated equally. But as most Hollywood stories go, this one also portrays the solution as one resolved by a lone hero. Showing a courageous soul who is willing to sacrifice his life is a good example. But Howard Zinn and Woodie Guthrie have both said that it will take millions of small acts to save the world. Here’s what Zinn said in an interview I did with him:

“How could you predict that four students,in 1960, would do is sit in Woolworth’s in Greensboro, North Carolina, and this would spark dozens and dozens of sit-ins and this would lead to freedom rides? In other words, there’s no way of predicting how a movement develops. All you can do really – you do your part, you do whatever you can, you organize with other people, you try to get some kind of change, and if enough people do enough things, even if they’re little things, they will add up. Because that’s what happens in movements: just millions of people doing small things which they cannot predict in it’s results.

And Woodiy Guthrie said, “A lot of little things, millions of little things is what will save this world.”

Last year, I interviewed, for my Bottom Up Radio Show, Chris Vogler, a movie consultant who wrote THE book, The Writer’s Journey, on incorporating Joseph Campbell’s concept of the Hero’s Journey into movies. I invited him on my radio show to discuss whether it was possible to make a movie in which there is an Occupy Wall Street, horizontal version of the hero’s journey, in which there are many people who come together, from the bottom up, to save the day. He jumped at the idea and opportunity to discuss it and came up with the term “collective hero.” Here’s an excerpt from the interview:

Chris: This reorientation you’re talking about of getting it off of this hierarchical, leave everything to the secret elite team at the top, which is the idea of “The Avengers” and rewriting this or redefining this is. No, this has to be from the people. The people in “The Avengers” movie are like sheep. There’s one woman who’s given a couple of lines and she’s supposed to represent all the people but she’s just like a big sheep looking up at, “Oh, the heroes they’re saving us. Oh, that Iron Man. He’s so cool,” or whatever it is. It’s a very weak attempt to acknowledge the power of the people. So, that’s something that I think we could grow more of this kind of consciousness in our story.

Rob: Of course the Marvel Comics brand is built upon this kind of superhero and I know Disney spent billions to buy the brand, right?

Chris: That’s certainly true yeah.

Rob: They’re investing in maintaining that kind of hero archetype, but I wonder, this is a question I’ve been meaning to discuss with you and we haven’t hit all the archetypes but I think we hit enough of them.

Chris: Yeah.

Rob: What’s the chance of a major movie company doing something like this?

Chris: Well, I think that the very fact that you have so many of the certain kind of the elite team of the G.I. Joe’s or whatever it is or exceptional heroes like Indiana Jones, the very fact that those have such dominance creates a hunger for the other thing, so then you can get back to more grounded collective things. And to be fair with Marvel Comics, the original idea of many of these things was more like the Spiderman model, where it’s just a kid and he’s put together a costume out of stuff from the junk store and old athletic equipment.

Rob: It’s true and actually some of the commenters from my article observed that many superheroes start out as average people who are victims of chemical spills or radiation or things like that.

Chris: Yeah, that’s a very interesting thing. Yes, there is some working out of maybe collective guilt about that or trying to show that there’s an interaction between these environmental choices and what happens. They’re very positive that way that usually the environmental change is positive. Not always, because some of the Batman villains, for example, are horribly deformed by it, like Two Face. It poisons their nature, but sometimes it brings out something good. Spiderman has these powers, but the whole point of Spiderman is the powers have to be used responsibly. So, if you’ve got this wonderful new tool of tablet computers and e-mail and so forth that has to be used responsibly as part of this hero contract.

Rob: When it comes down to making a blockbuster movie, underneath it there has to be a great story that people are going to care about and be able to relate to.

Chris: Um-hum.

Rob: Where the story will be able to lure them into the story trance.

Chris: Yes, that’s true and a couple of things may happen along these collective lines we’ve been discussing. One is that you present the collective hero like a village or a tribe or a street or a family or something like that and then the audience picks one or two that they like the best or that they relate to the most and so they kind of turn those into the heroes of the peace. The other thing you can do, and I like this idea, is to really spend some time creating a character that is that village or that street or that family so that the filmmakers use their tricks and techniques to create the sense of the community as a real entity that has its own consciousness and its own goals and settings, and that those need to be adjusted a little bit and that can be a great movie of material; a great piece of material. Something that shows us, here’s a microcosm of your society in one family or one street.

Rob: Has that been done?

Chris: Well, I think that this is what Spike Lee was after in “Do the Right Thing.” He was giving you of a sort of Charles Dickens view of this is a whole array of different types of people in this one location. I thought that was a successful effort there and you could pick out certain people and say, “Okay, it was really this guy’s story or that’s guy’s story.” But I think he did the right job there of creating the sense of the collective and that that itself can be a character. So I like things like that. Or another example from far a field from that, there was a movie about U-boats, “Das Boots,” and very clearly the intention there was the boat itself. The crew of the boat is a collective and this is the main character; not the captain, not anybody on the crew. It’s that boat. So, I think there are plenty of examples that show how you can do that very effectively. John Ford did it during the war a number of times. He took movies like “They Were Expendable,” where he was studying a certain unit and giving you the story that collective military unit. So, there’s lots of precedent for this.

It takes courage to make movies like this– for the studio, the actors, the director, the distributors. This is one movie I encourage you to watch. You’ll enjoy it, and you’ll show, financially, that movies with this kind of message can be economic successes too.

By the way, the Elysium official movie website has a number of interactive features, like an application to become a part of Elysium– that no matter what you answer, you fail. Of course, anyone seriously interested in such an elite program would not get in through an on-line application– they’d be invited, or would communicate with a real person. The application would just be for show. Think of the millions who applied for foreclosure relief.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rob Kall is executive editor, publisher and website architect of OpEdNews.com, Host of the Rob Kall Bottom Up Radio Show (WNJC 1360 AM), and publisher of Storycon.org, President of Futurehealth, Inc, and an inventor . He is also published regularly on the Huffingtonpost.com

|

(4)

ReThink Review: Elysium — The 1 Percent in Orbit

Posted: 08/09/2013

Neill Blomkamp’s latest sociopolitical sci-fi masterpiece, Elysium, is being called dystopian for portraying a world in the year 2154 where the ultra wealthy have abandoned an earth wracked by poverty, disease, crime, and pollution to live in the ultimate gated community aboard an orbiting space station. But if you read the news — which is full of stories about impending environmental catastrophe, the widening gap between the rich and the poor, and a republican party obsessed with lionizing the wealthy and making those in need suffer — Elysium seems more predictive than pessimistic. After all, the 1 percent already live in a world so different from ours — where they can flout the law, enjoy the best in medical care, and be untouched by the planet’s problems, concerns, and priorities — that they might as well be on another planet.

However, making on observation like that appears to be too much for the small minds of many, like republicans who have been quick to denounce Elysium as socialist liberal Hollywood nonsense, or others whining that Elysium‘s social commentary is simply too heavy-handed for the movie to be enjoyed. But don’t listen to either of them, since Blomkamp’s ability to weave sociopolitical themes into stunning, powerful sci-fi films is what makes him one of the best directors working today. And I was so blown away by Elysium that I need two reviews to describe why I think it’s the best movie of this summer by far, and probably of 2013. Watch my ReThink Review of Elysium below, followed by my take on why Elysium‘s sociopolitical commentary is so accurate, needed, and welcome.

Watch the reviews on Youtube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WKMtbwmkIp4

Source page for this article: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jonathan-kim/rethink-review-emelysiume_b_3730374.html

YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter.

Follow Jonathan Kim on Twitter: www.twitter.com/ReThinkReviews