By Kim Nicolini

Blowing the Pulp Out of Dixie

by KIM NICOLINI

By now, almost everyone who’s reading this has probably either seen Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained and loved or hated it, or feels they don’t need to see it to reach a conclusion. It’s not the sort of film to inspire a mild response. Django Unchained is a blood-soaked and bullet-fueled Spaghetti Western love story that takes on the subject of American slavery by making room for black characters in popular genre films that have predominantly been the territory of whites. Making copious use of the N-word, striking a delicate balance between the use of racial stereotypes and their dismantling, and exploding with blood, humor, violence, and pulp, Tarantino’s latest provocation, a worthy successor to the alternate history of Inglorious Basterds, leaves audiences unsure what to make of it, even as they cheer for its black hero.

Shouldn’t they despise the film for being so irreverent about the subject of slavery, which Hollywood has usually treated with sanctimonious reverence? Or does the film’s cinematic violence (both literally and generically) explode racism and bring the horror of slavery into a new, more visceral cinematic experience of the brutality of America’s role in the slave trade? I’ve seen the movie three times since it was released in December, and I have to confess that I have definitely reached the latter conclusion. I have yet to become bored with the movie. Nor have I been convinced that it’s racist or reactionary as some critics have stated. Ultimately, I see Django Unchained as a triumph against cautious liberal cinema, the safe packaging of slavery into distancing tidy narratives, and the limits typically imposed on black roles in popular Hollywood cinema. Django Unchained gives the audience a black hero who rises not only out of the abomination of slavery but out of the constraints of cinema itself.

Tarantino’s film has no pretense of being a reverent piece of historical cinema or a classic slave emancipation tale. In fact, Tarantino’s tale of slave revenge and romantic love in America’s Antebellum South intentionally disrupts history, much like its predecessor Inglorious Basterds, and blows-up the Big House of cinematic reverence to allow a mass audience to confront slavery and the role of blacks in film, thereby shining much-needed light on a very dark side of American history.

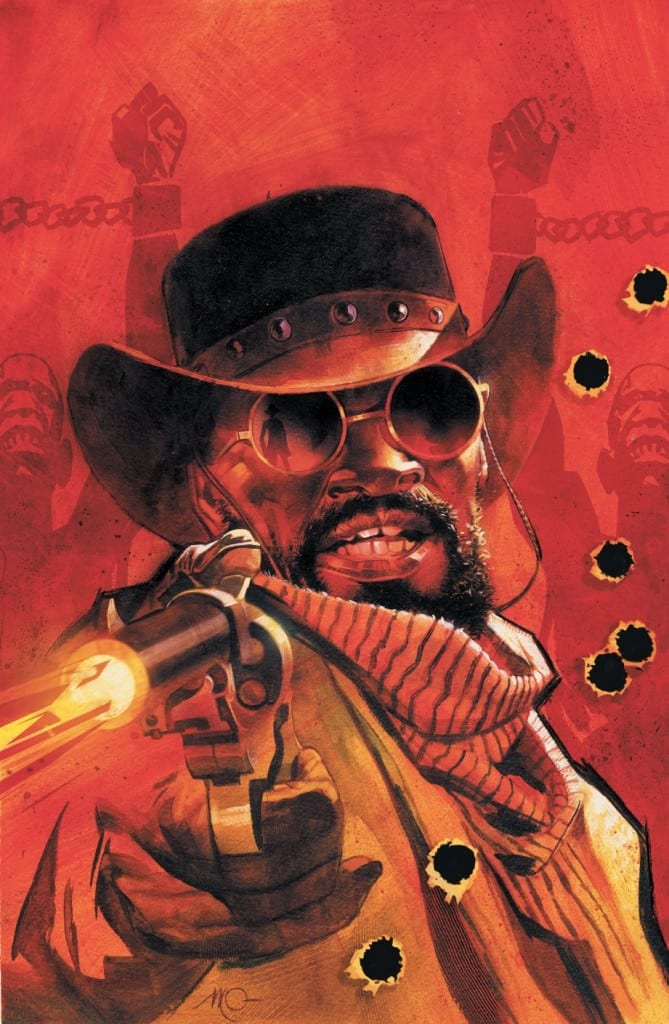

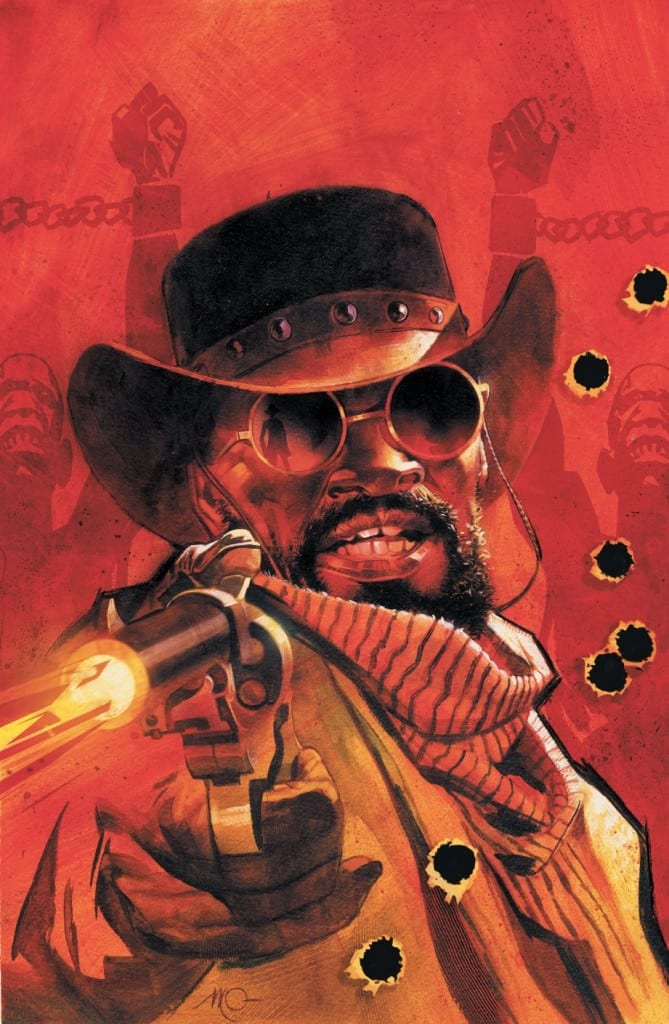

With the gun-slinging Django riding through the landscape and taking down bad white guys (and they are BAD!) to save his love and avenge his abusers, the movie does on many levels play like a mash-up of the Blaxploitation film and Spaghetti Western. Certainly, the movie contains elements of both genres, but it is also so much more. The film could be called a “Spaghetti Southern” (as Tarantino refers to it in the January 2013 issue of American Cinematographer). It takes elements of the Spaghetti Western (which features an outsider in an alien, hostile environment) and relocates them to the American South. What could be more alien in the Antebellum South than a gun-toting free cowboy black man? And what could be more hostile to this improbable icon of liberty than the white men of the South? As in a classic Western narrative, a very clear line is drawn between the “good” (the avenging slave and the man who freed him) and “evil” (the plantation owners and slave overseers) forces at play in the film, and, despite what some of Django Unchained’s critics have said, there is absolutely no doubt whatsoever about who we want to come out on top.

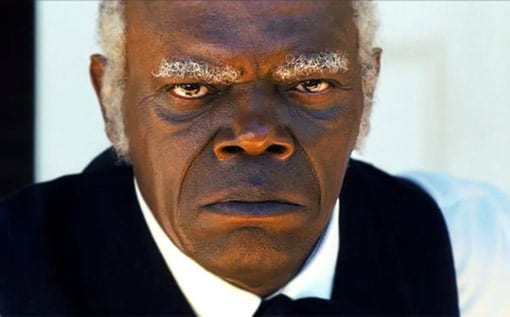

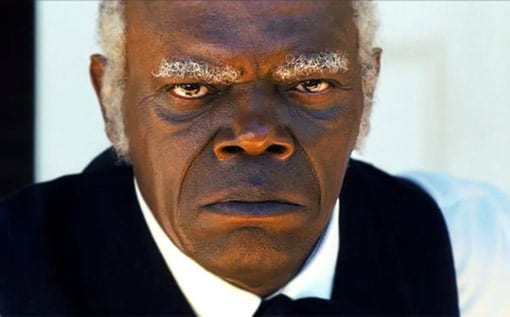

The black hero is Django (Jamie Foxx), a slave who is freed by a German bounty hunter Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz in a performance as great as the one he delivers as the slick “Jew Hunter” in Inglorious Basterds). Once freed, Django learns the trade of bounty hunting as a student to Schultz and demonstrates his sharp-shooting abilities as he plucks off any number of bad white guys with clean precision, a skill set he will eventually employ to rescue his true love Broomhilda. Following a classic fairytale structure, Django and Schultz travel to the evil kingdom (a Southern Plantation known as Candie-Land) to rescue the damsel in distress (Django’s slave wife). Leonardo DiCaprio plays the evil king/plantation owner Calvin Candie who gets his rocks off pitting slaves against each other in a blood sport known as Mandigo fighting, in which black men literally fight to the death for the entertainment of whites. And Samuel L. Jackson tears up the screen with his over-the-top performance as Stephen – the Uncle Tom “House Nigger” who is glued to Calvin Candie’s side and proves to be one of the most diabolical characters ever put on screen.

Just summarizing the main actors in the film illustrates the big can of worms contained in Django Uncained. Besides the role of an Uncle Tom, the shocking display of Mandingo fighting and Tarantino’s use of pulp genres like the Western and the Romantic Fairytale to tell a tale of the most brutal institution in American history, we have to take into consideration the use of the N-word which flies as hard and fast as bullets in this movie. I’ve already used the word in referring to Stephen as the House Nigger, and that is only one of multitudes of times the word is fired during the three hours of the movie. Some critics (most notably Spike Lee) have taken issue with Tarantino’s use of the word. How can a white man use the word “nigger” in a film?

Well, if we want to talk about the historical record, a tale of slavery in the South and the racist and violent history of the American economy would be hard to tell without including the N-word, unless the screenplay were as whitewashed as the pristine monuments to white supremacy that Southern plantations were. But whitewashed is exactly what has largely been done to the subject of slavery in film, and it’s about time that someone pulls the white sheet off the face of the subject. Shockingly, because it’s played for laughs, Django Unchained even features a sequence in which members of a proto-Klu Klux Klan are forced to do just that — pull the white bags off their heads. Revealing the ugly and brutal truth of racism means disrupting reverent expectations of the subject by mixing it up with pulp cinema, and that means deploying the N-word in rapid fire as frequently as it was used in the time. To paraphrase renowned slavery scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. from an interview he conducted with Tarantino, to tell a tale of slavery and racism in America and not use the N-word would be to lie. So if we’re going to tell the truth about slavery and racism, the N-word must be spoken. Just to be absolutely clear, then, if I use the word in this essay, it is both because I am quoting the film and the historical treatment of blacks it refuses to whitewash.

Well, if we want to talk about the historical record, a tale of slavery in the South and the racist and violent history of the American economy would be hard to tell without including the N-word, unless the screenplay were as whitewashed as the pristine monuments to white supremacy that Southern plantations were. But whitewashed is exactly what has largely been done to the subject of slavery in film, and it’s about time that someone pulls the white sheet off the face of the subject. Shockingly, because it’s played for laughs, Django Unchained even features a sequence in which members of a proto-Klu Klux Klan are forced to do just that — pull the white bags off their heads. Revealing the ugly and brutal truth of racism means disrupting reverent expectations of the subject by mixing it up with pulp cinema, and that means deploying the N-word in rapid fire as frequently as it was used in the time. To paraphrase renowned slavery scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. from an interview he conducted with Tarantino, to tell a tale of slavery and racism in America and not use the N-word would be to lie. So if we’re going to tell the truth about slavery and racism, the N-word must be spoken. Just to be absolutely clear, then, if I use the word in this essay, it is both because I am quoting the film and the historical treatment of blacks it refuses to whitewash.

Now that I’ve addressed the N-Word, let’s take a minute to think about what exactly Django Unchained is. The film opens in a dark Texas forest with a chain-gang of slaves. The black faces of the men merge with the dark forest, their white eyes glowing in the night. Two menacing white men on horses are leading the slaves to the market to be sold. This scene sets the stage for a traditional emancipation narrative. When Dr. Schultz arrives and frees Django, the camera closes in on Django’s bloody and brutalized ankle. Django’s entire foot and ankle fill the screen as Schultz removes the shackle and “unchains” Django. Django then shucks off his tattered blanket, bares his whip-scarred back and raises his arms in a gesture of freedom and vengeance (e.g. Black Power).

Certainly Django’s scarred and muscle-bound body could be seen as both a fetish object and a stereotype in this scene. This represents the traditional role of black men in film (when they’re not playing subservient emasculated “House Niggers” like Samuel Jackson’s Stephen). If Tarantino shows us this startling and unpleasant image, however, it is in order to set in motion a narrative that will undo racial stereotypes and cinematic expectations. He first creates the stereotypical scenario (the emancipated slave narrative), and then he dumps the black character into untraditional roles (the cowboy, the Western buddy, the chivalrous romantic hero).

Part of the reason Django Unchained succeeds in emancipating itself from the constraints of cautious liberal cinema and its safe historical distancing of the subject of slavery is by emancipating its main character from the trappings of traditional black roles in film. It undoes racial stereotypes by first exposing them and then either dismantling them by creating untraditional roles (Django) or blowing them up entirely (Stephen). Once Django shucks off that blanket and lifts his arms, he also shucks off the traditional emancipation story and everything that is expected from a “safe” film about slavery. Crucially, Django’s role isn’t so much to free the slaves as it is to free the image of the slave from the shackles of both the racism of classic Hollywood narratives and the political correctness of the post-Civil Rights Era.

Once Django Unchained leaves behind the traditional slave emancipation story, the story takes us through a variety of cinematic genres drenched with plenty of blood and humor as Django’s character develops and ultimately triumphs. Django Unchained uses popular pulp genres to take on the deadly serious subject of slavery and the bloody history of the American South. While some have criticized the film for turning the somber subject of slavery into pulp entertainment, the very fact that Django Unchained traffics in “low” stereotypes is what makes it effective. As we follow Django on his mission to save his wife through Tarantino’s network of pulp genres, not only do we grow to identify with Django, but we are able to share in his victory. Sure, guns are fired, walls are splattered with blood, jokes are made, and visceral violence plays before us, but through pulp, violence, and traditional popular narrative devices, Tarantino erases the cautious distance between the audience and his movie’s slave hero. We are able to feel, see and experience slavery without the desensitizing insulation of identity politics. This collapses the distance between the superficial safety of our times and the brutal reality of our history, making the horrors of the past more viscerally real than when they are neatly packaged in cautious historically accurate cinema.

To simply read Django Unchained as a slave revenge/blaxploitation/Western mash-up would short-change all the genre bending the film does to 1) effectively blow the fuck out of black roles in film and 2) make the audience identify with and cheer for the film’s black hero. When Django mounts one of his former captor’s horses and rides into a small Texas town with his emancipator Schultz, the film shifts gears, moving into the territory of the Spaghetti Western. We’ve seen this town before, its old wooden buildings and dirt-filled streets situated in the barren landscape between nowhere and nowhere else. White people walk out of buildings and stand on sidewalks shocked and outraged at the sight of Django riding on a horse alongside Schultz. One of the townspeople whispers, “Look! It’s a nigger on a horse!” When Schultz questions what their problem is, Django blatantly says, “They just ain’t used to seeing a nigger on a horse.”

The doubling of this line, first from the white woman and then from the black man is funny and the audience laughs, but it’s also damn true. Not only are the people in the town not used to seeing “a nigger on a horse,” but neither is the Hollywood audience. The Western is a white man’s genre, but Django rides his horse right through the genre when he rides into the town. This is partly how the film destabilizes white packaging of race in movies and in American history. When Schultz and Django force the town to accept the “nigger on the horse” because he is there as part of “legal business,” the audience also is being asked to accept him. And the audience does. All three times I saw the movie, everyone in the audience – black, white, old, young – cheered for this “nigger on a horse.”

It turns out that Schultz doesn’t just unshackle Django out of the goodness of his heart. Schultz purchases Django (and ultimately his freedom) because it is within his economic interest. Schultz is a bounty hunter, and he needs Django to identify three dirty, rotten overseers – the Brittle Brothers – for whom there is a large bounty on their heads. Django knows the Brittle brothers from his former plantation, because they are the men responsible for whipping him and his beloved wife Broomhilda. Schultz tells Django that he abhors the institution of slavery, but that even he will use it for his economic advantage. Since he “owns” Django, he insists that Django work for him to identify the men who have a large price tag on their heads. When Django asks what a bounty hunter does, Schultz explains that he’s “in the business of selling corpses.”

Coupling bounty hunting with slavery is brilliant. The pairing of these two businesses that trade in human lives underscores the business of violence in this country and the bloody legacy of the American economic landscape. Slavery was an atrocity, an abomination, a dehumanizing and brutal institution that was perceived as acceptable because it was good for “business.” It fueled one of the most successful economic enterprises in American history – cotton. Interestingly, Tarantino also shows how the race card can be thrown out the window, when it is within the economic interest of whites. Everything comes down to business. When Schultz realizes that Django is a perfect shot and that he would make an excellent business partner in the bounty hunting business, race becomes transparent between the two characters.

On the one hand, Schultz plays the role of teacher and liberator to Django, but on the other he treats Django with the equanimity that he would any other business partner. Schultz uses Django’s racial rage and taste for vengeance to his economic advantage. When Django learns what bounty hunting is and agrees to be Schultz’s partner, he says quite simply: “Killing white people for money? What’s not to like?” With Django’s help, the two hunt down the Brittle brothers, kill them, collect their bounty and formally enter a business partnership as well as a friendship.

It must be noted that “business” is at the bottom of much of the action in this movie, and with it the idea that race can become transparent when the money is good. Later in the film, even virulently racist plantation owners are forced to reluctantly accept Django – “the nigger on a horse” – because he is legitimized through the economic transactions in which Schultz includes him – slave trading, bounty hunting, etc. In a scene toward the end of the movie, Django is being transported to a mine where he is supposed to spend the rest of his life breaking down big rocks into little rocks. When Django offers his captors a way to earn $10,000 while he only requires $500 of it for himself, the men immediately free Django because it appears to be within their economic interest to so.

Underneath all this business, however, is the business of slavery, the abhorrent institution that was the backbone of the Antebellum Southern economy. While it may be in the economic interest of plantation owners to treat Django with respect, it is also in their economic interest to make sure that this treatment remains the exception to the rule of the color line. The veneer of civilized behavior that encompasses Django in his roles as bounty hunter and prospective Mandingo trader stands in blatant contrast to the brutal way in which the slaves all around him are dealt with (being fed to dogs or forced to fight to the death). Django’s safety depends on performing the role of exception without ever seeming to be upset by the treatment of his fellow blacks.

In one scene, as Django and Schultz are traveling to Candie’s plantation — which is known, in an example of the “black” humor that spatters the picture, as “Candie-Land” — under the guise of wanting to invest in the Mandingo trade, Schultz pulls Django aside and cautions him that he is playing his role of Slave Trader a little too exuberantly. Django reminds Schultz that their relationship is based on the bloody and violent business of bounty hunting in which Schultz had Django shoot a man and kill him in front of his son; that, in Schultz’s own words, they are in the “business of getting dirty.” This formulation provides Django his punch line, as well as an implicit response to those who accuse the film of being too violent: “So I’m getting dirty.”

Indeed, we are reminded time and again that American business is dirty and bloody. When Django shoots one of the Brittle brothers, his blood bursts across the screen spraying the fields of white cotton with red, literally showing the bloody business of the cotton industry and the slave trade that fueled it. In one of the most violent scenes in the movie, Candie sets his dogs on a slave and has him ripped apart in front of Django, Schultz, and the audience. Prior to killing the slave for refusing to participate in another Mandingo match (a fight to the death between black men in which white men gamble on the outcome, not unlike a cockfight), Candie berates the slave for being a bad business investment. He says, “I paid $500 for you, and I expect five fights for my $500. You only gave me three fights.” So Candie savagely disposes of his bad investment, while at the same time putting his economic investment in Schultz and Django to the test by observing how they react to the brutal slaying of the slave. When Candie notes that Schultz looks a little “green around the gills,” Django answers, “I’m just a little more used to America than he is.” In this sense Django literally embodies the violence of America.

Though Schultz and Django’s relationship starts first as slave and slave holder and then as business partners in the bloody business of bounty hunting, the racial divide between the characters soon evaporates, and the film shifts into a buddy movie. With Jim Croce singing “I Got A Name” in the background, the film moves to the mountains of Wyoming where Django and Schultz bond as buddies via the kind of montage familiar to fans of the Mountain Western. Images of the two of them riding their horses across the expansive Rocky Mountains, target-shooting on a snowman, and taking down their bounties as fountains of blood spurt in glorious red across the snowy background showcase a relationship as cinematically romanticized as Django and Hildy’s.

This segment of the film (the buddy film/mountain narrative) undoes traditional white narratives as much as the Spaghetti Western component, playing off another subgenre popular in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the mountain survival adventure. The friendship between Schultz and Django is really sealed after Django shoots his first bounty, and Schultz exclaims, “The kid’s a natural!” This clearly references Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, the archetypal Western Buddy Romance of that era. But instead of giving us two rugged white male sex symbols, Paul Newman (Butch Cassidy) and Robert Redford (The Kid), Tarantino provides us with two figures who are clearly outsiders in this landscape, a foreigner and a black man. This deviation from tradition radically destabilizes the romantic view of the West held by so many American conservatives and liberals alike, in which both the otherness of excessively refined men the East Coast and the Old World and that of the “savage” Natives (and black men) are held at bay by heroic white men.

The Wyoming sequence also references another Robert Redford film, Jeremiah Johnson, in which a veteran of the Mexican-American war flees to the Rocky Mountains, adopts a family, finds his wife and son slain by Native Americans, seeks vengeance and then ultimately finds reconciliation. It’s the reverse tale of Django Unchained, in which Django is the “colored” person seeking vengeance against the white man. In Jeremiah Johnson, the white man seeks vengeance against “the colored” only to have to accept that the white man really is the “violating other.” Referencing these Robert Redford films through a black slave narrative ruptures the white romantic view of the West (of which Redford is the ultimate icon ) and also underscores the persistent violence of America (both movies are bloody, violent and tragic). Violence is nothing new in America, and keeping it safely tucked away in romanticized narratives of the West or historical reverence masks the fact that the entire country’s economic backbone is based on violence (see blood-splattered cotton for details).

During their trip through the snowy mountains, Schultz tells Django the classic German fairytale of Siegfried and Broomhilda (after whom Django’s slave wife was named) – a young woman who is captured by the evil king and saved by her beloved – and the movie shifts gears again. Now Schultz and Django are on a different mission in which the fairytale meets the horror story of America’s bloody past. They travel into the Dark Kingdom of the Deep South as they head to Mississippi to free Broomhilda from her evil captor Calvin Candie. Setting a Western in the South and mixing in classic fairytale elements, the movie further undoes the roles of blacks in cinema by referencing gothic romance films, melodrama, and a chivalrous love story, none of which have ever been the sources of traditional black feature films. Further, the film uses elements of these genres to explode traditional romantic ideals of the American South and expose the brutality and blood that made its opulence possible.

The American South was created and fed on lies and exploitation. It prided itself on a false romantic identity from instituting ludicrous codes of chivalry to considering itself a Feudal society in which plantation owners were akin to landholding kings entitled to trade and exploit slaves for their economic gain. When Schultz and Django are situated in the South (in an earlier scene at Big Daddy’s plantation and later on the Candie-Land plantation), the cinematography fluctuates between sweeping romantic visions of the South and intensely close-up and unsettling violence.

One of the biggest jokes in the film is the outfit that Django chooses to wear when he and Schultz hit their first plantation as business partners. When Schultz tells Django he can pick his “costume” to play his role of “valet,” Django dons a blue satin costume that mimics the attire of in the 18th-century Thomas Gainsborough painting “Blue Boy”. The outfit seems ridiculously funny, but Django wears it like a dare and a weapon, understanding on some level that the outfit is violating all kinds of racial codes (in the movies and in the South). It emblemizes the way in which this black character is disrupting traditional white narratives and dismantling the romantic view of the South. In a way, it’s also the perfect metaphor for Tarantino’s filmmaking strategy in Django Unchained, so wrong in breaking with every social convention that it’s deliciously right. Because the outfit is also blatantly anachronistic — the Gainsborough painting appears to depict someone playing “dress up” in a 17th-century outfit — it alerts us to the fact that Tarantino’s movie — though it doesn’t deviate from the historical record as obviously as Inglorious Basterds, with its climax in which Jewish American soldiers assassinate Hitler — is not striving for the sort of accuracy fetishized in reverential historical films like Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln.

In the first scene set in the Deep South, when Schultz and Django travel to Big Daddy’s Tennessee plantation in search of the Brittle Brothers, the landscape is shown through the hazy diffused glow of a romantic painting. Django rides onto the plantation in his ludicrous blue satin outfit, seemingly the butt of everyone’s joke. He’s still that “nigger on a horse” but is now inside a different painting in which he doesn’t belong. For precisely that reason, though, Django is a force who simply cannot be ignored. Earlier in the film, Django experienced a brutal flashback of Hildy being whipped by the Brittle brothers. Django is on the scene to take vengeance, and the seriousness of the crimes committed against him and the woman he loves and his drive for vengeance clearly overrides the “joke” of his out of place character. As he walks across the plantation to find the Brittle brothers (where they are preparing to whip a slave girl for breaking eggs), we see more of the plantation through this pastoral lens, with the luscious green of the plantation interspersed with slave girls on swings. But Django is having none of it.

When he finds the Brittle brothers tying the girl to a tree, all romance of the South is ripped away as Django’s rage is unleashed. He shoots one brother right through a page of the Bible pinned to his chest (the white man’s religious justification for brutalizing a black woman and a short effective shot at the connection between religion, racism and violence in America). Django then picks up the whip and with unfettered ferocity whips the living shit out of the other brother. Shot from a low camera angle, the audience looks up at Django asa his whip comes down on the white overseer, and we occupy the place of the white man being whipped and are therefore the recipients of Django’s rage. However, rather than feeling victimized by Django’s violent attack on the white man, the audience feels exuberant and elated, despite the savagery of the beating. We are made to “feel” the extent of Django’s rage and the injustices committed against him and all slaves by being on the receiving end of the whip. During all three screenings of the film, the audience around me was both horrified and invigorated by this scene. Everyone cheered for Django, while at the same time gasping at the magnitude of his rage. It is a brilliant scene that allows the audience to occupy simultaneously the place of the black and white man. This brings me back to my point about how Django Unchained undoes Hollywood’s tendency to produce reverent and therefore safe movies about slavery. Nothing about this scene is reverent or safe. But there’s also nothing in it that paints Django as a victim. By exploding the conventions of the cautious cinema which tends to portray oppressed people as victims, the scene unequivocally establishes Django as the hero of the film.

Later, when Django and Schultz travel to Mississipi, this same fluctuating technique is used to make the audience experience 1) the brutality of slavery; 2) the explosion of the romantic Southern ideal; and 3) the victory of Django over his oppressors. When Calvin Candie enters the picture, the movie employs lusciously orchestrated scenes shot like sprawling melodramas. (Significantly, Tarantino has stated that his main cinematic reference for the interior shots in Mississippi was that master of the lusciously rich melodrama Max Ophuls.) But then the action cuts through all of that opulence with bloodshed and tragedy.

First there is the Mandingo fight at the Cleopatra Club, where Candie and the original Django (in a cameo by Franco Nero from the 1966 Sergio Corbucci film) watch two slaves fight to the brutal death. The camera alternates between pulling back and panning the rich opulence of the club’s interior, and closing in on the absolutely brutal flesh-on-flesh fighting between the two slaves. Blood, gore, violence and brutality meet manners and the sham of civility as Candie eggs on the fighters to kill each other. One man rips the other’s eyes out and then takes a hammer and “finishes him off” by bashing in his skull. The scene is unsettling in its violent content alone, but it is particularly effective because its ugliness (the dehumanizing violence of the slave trade) is found within an outwardly elegant setting.

When the group finally makes it to Candie-Land, further romantic myths come crashing down even as the romance of Django triumphs. First, we see the romantic image of Hildy shattered by the reality of her literal body being abused by the institution of slavery. Up to this point, (except for the flashback of her being whipped by the Brittle brothers) we have only seen Hildy through the romantic filter of Django’s flashbacks and hallucinations. She’s been a picture of the romantic ideal – smiling naked in a steaming lake in the mountains, wearing a yellow gown and waving to Django as he passes her on his horse, sitting beautifully dressed at a sun filtered table pronouncing her name (“Broomhilda, but they call me Hildy.”) But when we actually meet the “real” Hildy at Candie-Land, she is a runaway slave who has been thrown into a “hot box,” a kind of coffin where she has been sentenced to stay for ten days. Candie has her naked body pulled from the box, hosed down, and carted off in a wheelbarrow. By juxtaposing the romantic cinematic image of her — Django has just had more hallucinations of her in the yellow dress upon entering the plantation’s grounds — with the brutality of her “real” circumstances, the dehumanizing forces of slavery are brought devastatingly home. The image of her naked body stuffed into a wheelbarrow and carted across the sprawling lawn of the plantation is heartbreaking as we witness the intersection of the tidy grounds of the plantation colliding with the bloody and violent practices of the institution they stand for.

It is at the Candie plantation where Tarantino takes on another taboo subject within the institution of slavery: social stratification within the institution of slavery itself (“house niggers” versus “field niggers”) and between slaves and free men. Note that Schultz gives Django the surname of Freeman. The way in which blacks were pitted against each other within the brutal environment of slavery and the abominations that resulted are delivered most effectively through the “Uncle Tom” character of Stephen, played with diabolical relish by Samuel L. Jackson. The creation and destruction of Stephen’s role — he serves as a kind of foreman for Candie, keeping the other slaves in line — is critical to the liberation of Django and what he represents for blacks in movies and in cultural representation in general.

Jackson’s Stephen is a despicable traitor, glued to the side of his master Candie. He’ll sell-out anyone for his own benefit and security in “The Big House.” He holds onto a position of power even as a slave while he pulls strings and sets the film’s violent conclusion in motion. It is Stephen who advocates keeping Hildy in the “hot box”, who attempts to treat Django like a lower species (even though he shares the same black skin as Stephen), and who ultimately sells out “his own” to try to hold onto the position he has created for himself as an autonomous man of power. The house slaves fear Stephen as much as, if not more than, their real “master” Candie.

Stephen is a “race traitor” to cover his own ass, while Django plays the fictional role of “slave trader” to emancipate his love and himself. With Stephen and Django, Tarantino give us showdown where the baddest black man in the south goes against the biggest black sell-out. For Django to be the real hero and victor, he needs to kill that Uncle Tom and everything he stands for. When Tarantino asked Jackson if he minded playing Stephen, Jackson answered: “Do I have any problem playing the most despicable black motherfucker in the history of the world? No, I ain’t got no problem with that. No, man, I’m already in it. I’m working with my makeup guy now about the hair, the skin tone. I want this man to be fresh off the boat.”

Jackson takes the role and runs with it. He literally has his face painted darker so he can play the role in “black face”, thereby reminding is of the virulent racism evident in so many classic Hollywood films. Stephen’s role as it plays against Django and other characters within the film open up even more taboo subjects within American history and, more specifically, the history of cinema by showing that it’s not all black and white and that contention and class stratification existed for African-Americans during the era of slavery. This is a subject rarely addressed in popular cinema, where everything plays in diametric opposites, good and evil, nor is it addressed in reverent historical cinema where clear lines between victim and abuser are tidily maintained.

The extended dinner scene inside Candie’s Big House is brilliant. Merging Ophul’s melodramas with an ode to Fassbinder’s Whity, Hong Kong action movies and the Western, the scene builds with operatic tension. When Stephen exposes Schultz and Django as frauds, the shit and the blood hit the fan in a complex play between characters. Even though Schultz and Django eventually get what they came for (Hildy) for a very steep price ($12,000), that proves to be insufficient. Schultz needs to pay his own form of vengeance. In a way, Schultz is the cautious observant liberal, sympathetic but on some level clueless when he is first confronted with the ugly and brutal reality of slavery. When his remaining illusions are shattered and he has to accept his role in the violence he has witnessed, such as the execution of Candie’s reluctant Mandingo, Schultz shoots Candie through the heart. In a way, this is an act of suicide as well as vengeance because 1) Schultz can’t live with the truth he has had to face and 2) he understands that he has to die and sacrifice himself so that Django (his “buddy”) can truly liberate himself.

In the story, Schultz has no human connection other than to Django. He has no back story, no wife, or family. All of Schultz’s emotions are reflected through Django, so when he sacrifices himself for Django, he sacrifices himself for “love,” yet another twist in the melodramatic narrative. This realization is brought to the fore when Stephen runs in slow motion screaming in horror and grief at the murder of his master Candie, who, while hardly his buddy, serves as his equivalent love interest. So the two white men have died, and the two black men are left to fight for control.

And Django does fight. In an amazing sequence of flying bullets and bloodshed (the Hong Kong action sequence in the film), Django kills man after man in a shootout that leaves the white walls of the Big House literally dripping with blood, a painting in viscera and gore that literalizes the blood-soaked history of the United States. You’d think the movie would end here, but it doesn’t. In an unsettling turn, Django surrenders to save Hildy’s life. The movie abruptly cuts from Django as gun-fighting victor taking down bad white guys to a scene where we witness him hung naked upside down like a piece of cattle ready to be slaughtered. Django’s face is in a metal cage as he swings across the screen, his naked body, genitals included, exposed for us to see. This is by far the most unsettling scene in the film because we have cheered Django through his triumphs. We’ve followed Django on his quest and rooted for him with each shot of his gun only to see his humanity and his power stripped away from him.

We’ve watched Django transform into a hero, only to witness him hung-up like so much meat. When Candie’s henchman starts to take a molten hot knife to Django’s balls, the emasculation of the black man by the abhorrent institution of slavery becomes painfully literal and tragic. This scene is as effective as the scene with the whip when we are asked to feel Django’s rage, because by this point we fully identify with Django as the hero of the film. When his humanity is so brutally stripped away and the ugly truth of slavery stares us in the face, we wince and feel the horror of slavery more than we ever would in a safely whitewashed historical drama.

Thankfully, Django’s nuts are rescued when Stephen steps into the picture. Ironically, the Uncle Tom figure proves to be Django’s savior because he wants his enemy to suffer a painful captivity rather than risk him bleeding to death from being castrated. Stephen encourages Candie’s sister Laura to send the rebel off to a mine where he is destined to spend the rest of his days reduced to being a number chiseling away at rocks. When Django receives his sentence from the treacherous Stephen, we remember that this fate is pretty much the sentence of all slaves in the country. They were numbers who worked until they died or were killed. But this is not Django’s fate, because Tarantino has made a romantic love story with a black hero who must prevail. Unlike, traditional Westerns, Django is not out only for himself. He finds a way to make it back to Candie-Land to save his love and to avenge his race by blowing the fuck out of the plantation, Stephen’s Uncle Tom character, and everything they stand for in American history and cinema.

The three times I watched the movie, the entire audience – black, white, old and young – cheered for its black hero when he victoriously saves his girl and blows up the white world of slavery. Django is unequivocally the hero of this movie. Much fuss has been made about the screenplay and how Christoph Waltz and Leonardo DiCaprio supposedly steal the film and have all the dialogue while Jamie Foxx just hulks around scowling. I’m sorry, but if Jamie Foxx wasn’t doing an effective job acting, then we would not be cheering for him as he blows up a Southern plantation and rides off into the sunset with the love of his life. Django/Jamie Foxx is the catalyst of the film despite how many lines of dialogue the white actors have. We have to remember that he is playing a black man in the white dominated South, so it is a world where white people do most of the talking.

Schultz may have more lines, but he is not the hero of this film. It is Django who the audience cheers for. Every time Django puts his hand on his gun, absorbs his surroundings, acts according to the circumstances into which he is thrust, or takes down a bad guy, Jamie Foxx is acting and we are rooting for him. Acting isn’t just talking. Foxx creates a character who we care about through body language, eye movement, and dialogue. At the end of the movie, we would not have the same response of victory and elation if Schultz were the one to free Hildy. It has to be our hero Django, and Jamie Foxx makes us care about him.

Others have criticized the movie for being a “mainstream Hollywood” production. But I have to ask: don’t we want a mass audience to revisit slavery with a black hero rather than keeping the subject safely tucked away in reverent historical narratives that holds slaves captive in the role of victims? Reverence distances us from the subject; it has the potential to dehumanize its subjects and turn people into victims which then become a cause. By placing his story in the guise of a western romance and using pulp as the medium to deliver the story, Tarantino turns the victim into the victor. Put the history of slavery into a Western Romance story, load it up with guns and revenge, bring the camera in for close-ups on the violence and atrocities of slavery, give us a black hero who takes out a shitload of white oppressors and a movie can reach audiences across the racial divide. We can experience an abominable time in American history in a new light, one that exposes where we came from, acknowledging the blood-soaked history of a country that was built on the “business” of slaughter and human trade, but still leaves us with hope for the future.

Some have also argued that Django Unchained is irreverent cinema that disrespects the seriousness of slavery. After all, the film does explode with gunfire, blood, brutal violence and uproarious humor, all communicated through the sort of genre mash-up for which Tarantino is famous. But it is because Django Unchained disrupts reverent historical cinema that it is able to bring a new awareness of the brutality of slavery to the millions of people who are going to see it, black and white. In Django Unchained we’re laughing; we’re horrified; we’re disoriented; and we’re soaked with a lot of blood. But the whole while, the audience’s allegiance never fades. We want Django to win.

Yes, in Tarantino’s film, there are slaves in shackles, being whipped, wearing cruel devices, strung up by their ankles, chained and marching through mud, but as black slavery scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. notes, things were “Ten thousand times worse in real slavery.” If the film barters in stereotypes to fit this terrible legacy into a story that mass audiences will want to see, it is in order to deconstruct them in the way Americans know best: by blowing the living shit out of them.

Since Reconstruction, we have had plenty of somber stories of slavery where the subject is held at safe historical distance. Slavery was the brutal, ugly, inhuman, cruel, sadistic exploitation of black human beings for the economic benefit of American whites. There is not one thing about it that is pretty, tidy or easily packaged. Traditionally, this abomination of American history has been treated with reverence and neatly packaged in acceptable narratives. It has been approached with caution because it is such an abominable part or our history and is the source of many taboos. We have only been able to look at it through the safe lens of historical narratives or politically correct identity politics.

But walking the cautious line of politically correct films does not affect change. It only tells us the same story on a different day. Sure, Tarantino turns what has been perceived as the acceptable cinematic packaging of slavery on its head. Yes, he has created a film for mass audiences, one which is as entertaining as it is repulsive, but in the process he has raised more consciousness about the reality of American history than cautious liberal cinema ever could. In the end, Django Unchained is effective precisely because it is not safe. It places slavery within the broader context of culture, cinema and history, dismantling traditional roles of blacks and the cautious representations of slavery they sustain. Django Unchained packs a punch that is hard to take, yet impossible to resist, and in doing so delivers truly transgressive and effective cinema for the masses.

Kim Nicolini is an artist, poet and cultural critic living in Tucson, Arizona. Her writing has appeared in Bad Subjects, Punk Planet, Souciant, La Furia Umana, and The Berkeley Poetry Review. Another of her essays on film is The Best Film of the Bush Era? Stoner Dudes Explain Torture, Racism and American Hysteria. She recently published her first book, Mapping the Inside Out, in conjunction with a solo gallery show by the same name. She can be reached at knicolini @ gmail com.

Kim Nicolini is an artist, poet and cultural critic living in Tucson, Arizona. Her writing has appeared in Bad Subjects, Punk Planet, Souciant, La Furia Umana, and The Berkeley Poetry Review. Another of her essays on film is The Best Film of the Bush Era? Stoner Dudes Explain Torture, Racism and American Hysteria. She recently published her first book, Mapping the Inside Out, in conjunction with a solo gallery show by the same name. She can be reached at knicolini @ gmail com.

Eric Draitser is an independent geopolitical analyst based in New York City and the founder of StopImperialism.com.

Eric Draitser is an independent geopolitical analyst based in New York City and the founder of StopImperialism.com.