REVISITING AMERICAN SNIPER: Racist Propaganda and American Empire

![]()

//

The woods are full of soldiers who served in the US military and later bitterly realized they had been used. Kyle was certainly not one of them. He never got it. He never realized whose interests he was really serving.

With Hollywood and TV still serving the same chauvinist trash, another look at this celebrated piece of imperial propaganda is in order

by Mike Kuhlenbeck

[Original iteration: March 6, 2015]

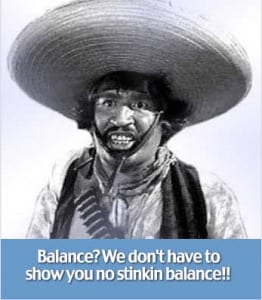

The filmmakers’ defense of “American Sniper” as “apolitical” is belied by the lack of any depth or humanity in its Muslim characters.

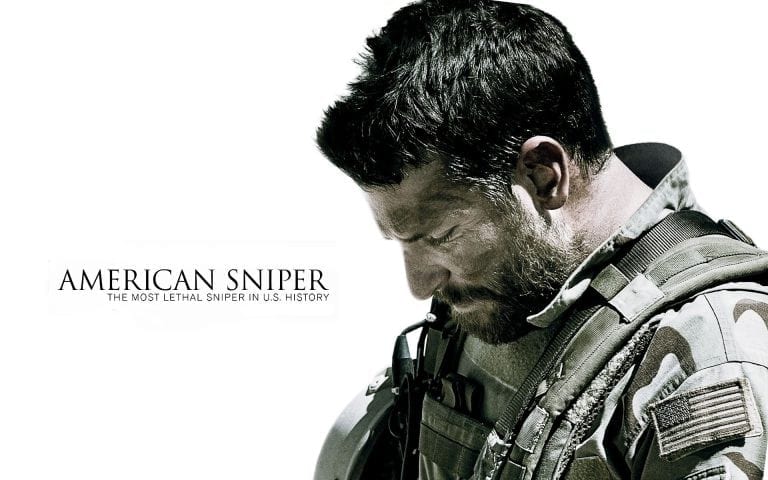

The film version of American Sniper has grossed well over $300 million at the US box office, making it the most profitable piece of pro-war propaganda in the history of American cinema.

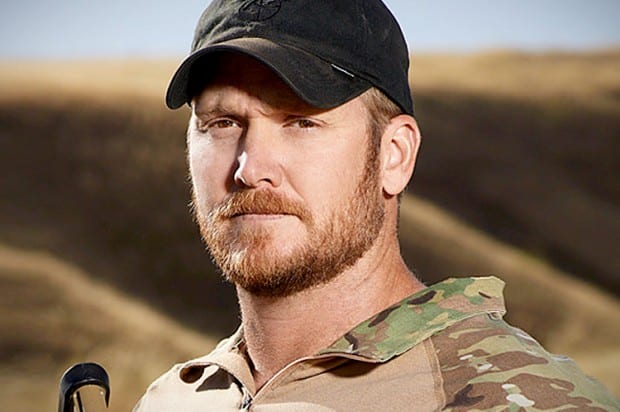

Since the release of American Sniper, it has either been praised for its patriotic (nationalist) overtones or has been ridiculed for distorting the reality of so-called “War on Terror.” The film is based on the bestselling autobiography of Chris Kyle, a man who had a talent for telling tall tales and bragging about his 160 confirmed kills (though he claimed the death toll was closer to 255). The widespread public support for Kyle’s actions and attitudes reveal how racial prejudices are manipulated in times of war.

A poster for the film American Sniper directed by Clint Eastwood and starring Bradley Cooper in the title role

Kyle’s autobiography, co-written by Scott McEwen and Jim DeFelice, was published in 2013. Although the book has been placed under scrutiny by various journalists for its factual accuracy (or lack thereof), it provides a fascinating glimpse into the mind of a soldier that is quite similar to many others who served in the American military in the Middle East. He gleefully boasted about his kills, deluding himself to the point where he forgot he was killing human beings. “Just because war is hell,” he writes, “doesn’t mean you can’t have a little fun.”

The dehumanization of entire populations is used in boosting public support to carry out imperialist objectives. With the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, pundits and news networks made stereotypes out of Muslims by portraying them as violent fanatics and suicide-bombers. In the toxic atmosphere created in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, Americans were conditioned on a daily basis to fear darker-skinned people, especially if they had Arabic names.

Pro-war conservatives in the corridors of power, who often morally justify wars that are not morally justifiable, like to point to such Kyle gems as his self-righteousness take on Islam, “Isn’t religion supposed to teach tolerance?” Passages like this are countered by statements like, “I don’t shoot people with Korans—I’d like to, but I don’t.”

American Sniper filmmakers, particularly lead actor Bradley Cooper and director Clinton Eastwood, have defended the film as “apolitical.” The lack of Muslim characters with depth or humanity in the film demonstrates the contrary. As described by Abed Ayoub and Khaled A Beydoun, writing for Al-Jazeera, “Redeploying age-old Orientalist images, the film’s Iraqis are thinly constructed foes of the democratic and divine – who must be methodically gunned down for both God and country. A belief, in the US today, that is far more fact than fiction.”

Such perceptions were evident with Kyle, in both interviews and in his own writings. “I hate the damn savages,” he writes. “I couldn’t give a flying f**k about the Iraqis.” Although he has been criticized posthumously for his choice of words and general attitude against Iraqis (among other things), it is far from being scarce among US soldiers.

Take the following passage from another American soldier: “The scene reminded me of the shooting of jack-rabbits in Utah, only the rabbits sometimes got away, but the insurgents did not.” This would appear to be written by a current American soldier, maybe one who enjoys hunting, watching action films and going to rodeo shows like Kyle did. But this letter excerpt was written by Fred D. Sweet over 116 years ago.

The letter was published by the Anti-Imperialist League in their 1899 pamphlet entitled Soldiers Letters: Being Materials for a History of a War of Criminal Aggression. This pamphlet contained numerous excerpts from letters written by US soldiers who were stationed in the Philippines during the Spanish-American War, which started in 1898.

During US President William McKinley and Vice President Theodore Roosevelt’s reelection bid in 1900, the campaign against Spain was justified with the following phrase: “The American Flag has not been planted in foreign soil to acquire more territory but for humanity’s sake.”

Teddy Roosevelt as a Rough Rider. The man, like many juveniles, liked to play soldier. His war obsessions and ideas of manhood created mayhem and cost one his sons his life.

US leaders are still declaring wars that are allegedly “for humanity’s sake” but are really for the sake of war profiteers and their allies.

History books, for the most part, have often failed to explore the racist attitudes of McKinley and Roosevelt. Their views were partially based on the theories of early eugenics and Social Darwinism that suited elitists like themselves. They believed that the Anglo-Saxon race was superior to all others and its strongest disciples had every right to inherit the world through conquest. This was evident in their ambitions to fly the America Eagle over foreign territories, directing it to dig its talons into these lands and fly away with stolen treasures.

Art is an effective conduit for portraying war as a noble cause to unite the masses in a common struggle. British author Rudyard Kipling is perhaps best-known as “the poet of the British Empire.” He penned “The White Man’s Burden,” a racist poem published in McClure’s magazine in 1899. The poem caused a stir for glorifying America’s involvement in the Philippines. References of “sullen peoples” as “half devil and half-child” fall in line with the stereotypes depicting people in undeveloped parts of the world as “savages.” Kipling writes that it is the duty, nay the “burden,” of white men from “civilized nations” to bring the Filipinos up from their “lowly” status.

Racial hatred combined with military force has been common with every war since the close of the 19th Century. The terms “savages” and “heathens” are used in many of the letters published by the Anti-Imperialist League, reflecting the hostility of troops sent over to the Philippines between 1898 and 1905. The Filipinos were often called “Pacific Negroes” or simply “n***ers.” Journalist H.L. Wells writes, “There is no question that our men do ‘shoot n***ers’ somewhat in the sporting spirit.”

Sam Jaffe portrayed the pathetic Gunga Din, whose chief aspiration in life was to serve and die for the British empire. He got his wish. (Still from the film, with Cary Grant).

“Most national myths, at their core, are racist,” writes Chris Hedges in his 2002 book War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning. Even though the racist attitudes of the early 20th Century are not as prevalent as they once were in American society, they still exist and US leaders know how to play on fear and ignorance in order to get what they want.

Soldiers are trained to accept these perceptions as true, making their duties easier when confronted with violent situations. This mentality is still alive in the 21st Century. Today such terms would be applied to Muslims and Arabs, including modern terms like “raghead” and “sand n***er.” Once American Sniper hit theaters, some people once again fell under a dark spell, one that never truly lost its power. People flocked to social media outlets and posted statements like “Nice to see a movie where the Arabs are portrayed for who they really are—vermin scum intent on destroying us.” In more extreme cases, some said the film “makes me wanna go shoot some f**kin Arabs.”

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he epidemic of “yellow journalism” under the control of moguls like William Randolph Hearst was the equivalent of today’s 24-hour cable news networks in whipping up fear and hatred against the people of “enemy nations.” For Hearst, a war against Spain meant selling more newspapers and increasing his personal fortunes. Also, it would give him positive publicity and the image of patriotism that would help fuel his failed political career.

As reported by PBS.org: “Today, historians point to the Spanish-American War as the first press-driven war. Although it may be an exaggeration to claim that Hearst and the other yellow journalists started the war, it is fair to say that the press fueled the public’s passion for war.”

In the early 2000s, Australian-born billionaire Rupert Murdoch, owner of the Fox News Channel, followed the Hearst tradition by supporting the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. The network’s slew of cookie-cutter commentators espoused views that democracy would be delivered to these countries along with Christian bibles, ammunition and American flags. Conservative author and frequent Fox News contributor Ann Coulter is the same woman who quipped, “We should invade their countries, kill their leaders and convert them to Christianity.”

Though not as eloquent as the slogans produced by the administrations of McKinley and Roosevelt, such calls to action are what such declarations of war amount to.

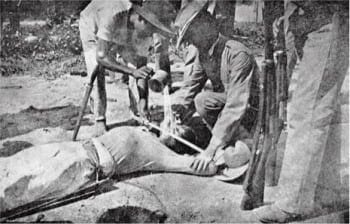

In the Philippines, concentration camps were built to detain Filipino combatants and civilians and the use of torture were implemented by US troops. Even the practice of waterboarding was used by US troops, using canteens and metal cups filled with salt water to simulate drowning. As observed by historian James Bradley in his study The Imperial Cruise, “When the Japanese later waterboarded U.S. personnel in World War II, America tried them for war crimes.” These institutions are no different from the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq and the US government-sanctioned torture chamber in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Such atrocities are the natural byproducts of imperialist expansion.

We’ve been at it for along time. Water torture being used by US marines on a Filipino patriot. (1902)

The most intriguing justification for the film is its sympathetic portrayal of soldiers suffering the trauma of war, a problem that has been ignored for too long. The horrific conditions of war have massive physical and psychological effects on soldiers. Instead of blaming their leaders for betraying their trust and sending them to other countries based on false pretenses, they are often desperate enough to blame civilians of occupied nations for why they are there. This seems evident in Kyle’s writings and those belonging to other soldiers. These sentiments were common among soldiers during the Philippine portion of the Spanish-American War.

“The boys are getting sick of fighting these heathens,” writes Tom Crandall of the Nebraska Regiment (1899), “and all say we volunteered to fight Spain, not heathens. Their patriotism is wearing off. We all want to come home very bad. If I ever get out of this army I will never get into another. They will be fighting four hundred years, and then never whip these people, for there are not enough of us to follow them up…The people of the United States ought to raise a howl and have us sent home.”

There are, however, those who are forced into such circumstances and refuse to fall for the propaganda of their governments. Whatever illusions they had before entering these conflicts disappeared when confronting the grim realities of war.

The mainstream media has been ignoring another American sniper named Garett Reppenhagen, who has since left the military and has dedicated himself to the antiwar movement. When he saw the film, he criticized it for what it was: racist agitprop glorifying a man who has been called a borderline psychopath and habitual liar.

The mainstream media has been ignoring another American sniper named Garett Reppenhagen, who has since left the military and has dedicated himself to the antiwar movement. When he saw the film, he criticized it for what it was: racist agitprop glorifying a man who has been called a borderline psychopath and habitual liar.

In The Acronym Journal, Reppenhagen said:

“You feel like there is this debt that you build for every life that you take. You feel like you owe the world something because you left it without this other person that could have done something amazing. I think about all of these soldiers coming out of the U.S. military and helping them get jobs and education and hearing about what they aspire to do and be in the world. And I wonder about all of the Iraqis, Syrians, Albanians and others that we killed in that country and what they aspired to be.”

There are countless other soldiers like him, who had the intention of protecting their country and liberating an oppressed people but did not see the reality through the dense black fog of war.

In another letter from the Spanish-American War pamphlet, signed by General Reeve: “I deprecate this war, this slaughter of our own boys and of the Filipinos, because it seems to me that we are doing something that is contrary to our principles in the past. Certainly we are doing something that we should have shrunk from not so very long ago.”

Though the locations and populations have changed, the motives behind war hysteria have not.

Mike Kuhlenbeck is a journalist, photographer, researcher and media critic based in Des Moines, Iowa. He is a member of the Society of Professional Journalists, Investigative Reporters and Editors and the National Writers Union UAW Local 1981/AFL-CIO.

Mike Kuhlenbeck is a journalist, photographer, researcher and media critic based in Des Moines, Iowa. He is a member of the Society of Professional Journalists, Investigative Reporters and Editors and the National Writers Union UAW Local 1981/AFL-CIO.

Kuhlenbeck works as a reporter for Iowa Free Press and as a freelance journalist. His work has appeared in publications such as The Des Moines Register, The Humanist, Z Magazine, Foreign Policy Journal, Eurasia Review, People's World, The Palestine Chronicle, Paste, Little Village, Industrial Worker, Earth First! Journal, Intrepid Report and the National Writers Union newsletter.

His extensive and wide-ranging reportage has covered a myriad of subjects including news, politics, social issues, entertainment and local events. His work has been published nationally and internationally, and has been translated into numerous languages. His work has been cited by the Social Justice Journal, CopBlock.org, Axis of Logic, If Americans Knew, The Constantine Report, OMNI Center for Peace, Justice & Ecology, Isocracy.org, Zero Books, Global-Politics.eu and Vermonters for a Just Peace in Palestine/Israel. He has been working in the journalism field since 2006 as a writer, reporter, researcher and photographer. He has also worked for The Challenger, The Urban Vibe and The Grand Views, reaching thousands of readers during his tenure. His skills evolved when he enrolled at Grand View University, where he graduated with a BA in Journalism in 2011. During that time he worked in various capacities for the Grand Views and the literary journal Bifrost.

Note to Commenters

Due to severe hacking attacks in the recent past that brought our site down for up to 11 days with considerable loss of circulation, we exercise extreme caution in the comments we publish, as the comment box has been one of the main arteries to inject malicious code. Because of that comments may not appear immediately, but rest assured that if you are a legitimate commenter your opinion will be published within 24 hours. If your comment fails to appear, and you wish to reach us directly, send us a mail at: editor@greanvillepost.com

We apologize for this inconvenience.

Nauseated by the

vile corporate media?

Had enough of their lies, escapism,

omissions and relentless manipulation?

Send a donation to

The Greanville Post–or

But be sure to support YOUR media.

If you don’t, who will?